interview with robert melville, head of design at McLaren automotive

all images courtesy McLaren automotive

robert melville is the head of design at McLaren automotive in woking, UK – a luxury manufacturer of technologically advanced high performance sports cars. at McLaren, melville oversees the product and design strategies – under the direction of frank stephenson – and has been working for the company since 2009. prior to Mclaren, melville was the senior creative designer of GM’s advanced design in the UK and designer at jaguar landrover; since then he has worked on hypercars such as the McLaren P1 and 650s, and cross utility vehicles such as the range rover evoque.

in the second part of the three part series, designboom travels to england to speak with melville at the foster + partners-designed headquarters on his past experiences, current philosophies and future visions for the company:

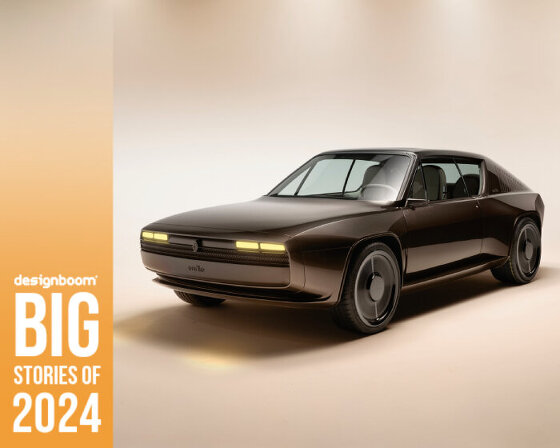

McLaren special operation P1

designboom (DB): can you explain your role as head of design at McLaren?

robert melville (RM): as head of design, the key thing is to inspire people, and to enable people do their job well around you. so I think it’s multi-faceted, but the key message is to inspire the other around you. in my position, different to when I first started out as a junior designer, now I need to look at the product strategy, the brand DNA, what the brand DNA can be, or should be because of the formula one tie. you need to be outward looking at the rest of the company. you can’t be purely selfish and think ‘OK, this car needs to be just this by being a McLaren’. it’s got this layer as a product, it’s not just ‘it looks cool’, it needs to be functional, so you need to make sure you choose the right materials, that suit the purpose of the job. but the main thing, again, the marketing, the conceptual side, the strategic side, the new product opportunities, sort of feeding that into the rest team, so they can take the thread of the DNA and input that into all the new sketches, and new designs – then everyone starts to get this sort of family feel. so then we know, ‘OK, what would a boat look like if it was a McLaren, what would a motorbike be. but you need to able to tell it to McLaren.’ even whether it was a knife and fork, a piece of furniture, you should be able to apply our philosophy to that.

so really, my job is to relay that message around the whole team, and make sure they have the right tools to do their job, and day-to-day talk to the designers, you know, work on the sketches, on the proportions. we need to make sure we don’t propose things that aren’t possible – you need to propose things that are cutting edge, look like concept cars, but you can make them. you can’t just repeat what other companies have done over the last 50-60 years. we’re kind of new on the block, so we need to do everything for a reason – which is kind of one of our mantras – the car needs to tell the story, we’re looking for this new visual narrative of the car. as you walk around the car as customer, you need to be able to work out the way the air flows over the vehicle, and it tells its own aerodynamic story.

DB: how exactly did you end up here at McLaren?

RM: basically, frank stephenson, the design director at McLaren gave me the phone call, it was friday night, I was late on the floor, taping the back end of a big cadillac sedan. it was around 8 at night, and I got this phone call, answered it – and it said ‘hi it’s frank, I’ve been given your name by someone who used to work for me that recommended you’, and I was like ‘OK, who is it?’ ‘my name is frank stephenson, I’m at McLaren’. so it was music to my ears, GM was at a real struggle at the time, they were about to go bankrupt. so for me, when your looking down the barrel thinking, ‘what’s my next career move’, to phoned up, and to be asked to come for an interview – it was good timing anyway.

so I came down for the interview, literally the next day, I said to the guys at GM – I didn’t tell anyone – I said, hey guys I need to leave. left, literally the next day, jumped into my car, drove straight down, did the interview, and frank seemed really happy. but it took 6 months to hear back, so I think he interviewed most people – and I was the guy that got lucky and got the job. so it went from that friday night, sitting in clay taping the back end of a cadillac, and six months later, I was here, starting on this kind of new exciting journey of forging what McLaren might be, the new product line up – a dream come true really.

DB: how did you get introduced into the world of car design?

RM: my dad and brothers, I was the youngest of the 3 brothers. my dad was a real car nut. he always used to love AUDI quattro’s, and my brothers were the same, they were always reading his car magazines, so I thought ‘yeah, yeah how could I do this?‘ – my dad was an engineer. I used to draw boats, cars, planes in my spare time as a kid. and my dad would sit with me and say ‘you could turn it into this, or make it into this’, and we’d develop things like santa’s sleight, or you know – I would always be drawing some kind of vehicle. and as I got older, my tutor at school – he was an ex-motorbike designer, so that was a quite a good influence at the right time. he told me ‘you have to go to art college’, so I went off there. and during art college I enjoyed photography, I enjoyed fine art, print making, but the thing I always came back to was 3D design.

people always told me ‘you could never make it into car design, only like 1 percent only ever get to do that.’ it’s harder to do that than get a drive in an F1 car apparently. and I thought, ‘there’s got to be a way’, so I persevered, worked hard and got into a course doing vehicle design up in huddersfield. that course has since shut down, and from there I went to the RCA. the 2 years there were key, I think it really introduced a lot of the people in the industry – I was sponsored by jaguar land rover at the time, so that was great, it helped me pay for a decent life in london. and from there, I went there to work as a professional.

DB: what was the aesthetic inspiration for both the P1 and the 650s?

RM: well they were clearly two different cars, the 650s was based upon what was the 12c and the P1 was an all new carbon tub, or modified tub. so, with the P1, first of all, I think the key there was to really start to forge this brand identity of the surface language. so as I was saying earlier, the surface language can’t be just, ‘oh, it’s trendy, it’s cool, it’s the new thing.’ it has to be, ‘okay, it communicates what the formula 1 cars have done.‘ so in a broad-brush sense, I think it was inspired by formula 1, in the sense of shrink wrapping, choosing the correct sections and radii to steer the air around the car. from a mood board point of view, which maybe some people are familiar with that phrase, we would have images of sharks, manta rays, stingrays, fish, sailfish. so frank got a full sized sailfish shipped in from miami. um, it’s full of drugs probably (laughs). and that’s up on the wall in the studio. and that was trying to communicate this message of bio-mimicry.

so looking at bone structures, taking weight out. the P1 definitely has through the door. communicates this idea of layering, and skeletal, this thing with the tendon across the door, and the graphics and the way the seal has been hollowed out. so when you open the door you can see down inside the door seal. but yeah, bio-mimicry, layering, and the idea of when you layer, it implies a material has been removed from underneath. it implies it’s lean, it’s light. so it’s the consumer again, not only does it allow us to pass air underneath and have heat inducting – but when you get close to the car, you can see it’s like an athlete, it’s been trimmed up, it’s lean.

for the 650s, that kind of has a different story. I wasn’t involved with the 12c originally, but when 650s came along, the idea for that one was to take some of the work we had done on the P1 and then start to introduce it onto that vehicle. so with all the technical upgrades it’s basically like a different car, it’s like a new car. visually, we had certain restrictions, certain panels we carried over, but the idea was to start to get the family face on the front and on the rear as well. the idea of the open area, the le mans-inspired meshes and get you all that hot air out the back. it was really just to tie out the thread across from P1.

DB: would you say your work has changed from early in your career until now?

RM: I’ve been working professionally now for about 13-14 years. so from the early days I was working very different products – jaguar and land rover and things like this. but in terms of the style and the thinking, I think my strong point was always the conceptual thinking, and the planning, the strategy. and seeing how the models would fit into the showroom and what kind of story we would need to tell. but things I’ve improved on since then are: selling proportions. doing land rover’s was great for that. it was all about the ways it performs and using the proportions to tell the story about what the car’s function was. so getting all the proportion work in now and, again, going from a lot of cars – cadillac where they worked with a very hard crease to developing new ones here where it’s all about changing radii and soft fluid forms like porsche.

I think that’s been really interesting to have this contrast of different projects to work on in about a decade’s time. but I think the main way it’s changed, I’m not sure if it has changed though if I’m honest (laughs). if I’m really honest, I think I’ve just always been driven by the same passion, but now I’m able to see if I need to get from A to B I’ll go there in maybe one or two steps whereas I used to take maybe five or ten steps to get there. so I’m able to see the opportunities to chop down the workload and get to the answer far quicker.

so I’m far more efficient in the way I work. that’s the thing that has changed. far more efficient. and I think that’s from having to juggle the timing, the marketing aspects, the engineering aspects, the product strategy side. and because you’re looking at the bigger picture you kind of think, ‘okay, if this car delivers this, then the next car, as we develop that one, the new one comes on. well okay, we need this one to do this.‘ so because you’re spinning all the plates at once, you can see which one needs a bit more spin or which one needs slowing down and you’re able to think that they all find their place and they all find their rhythm. and then, in the past I would have struggled to keep them all going. I think that’s the main way in which my work or my input at work has changed.

video © designboom

in terms of the design side, I think I’ve only improved at sketching and those kinds of things, but it’s just the same here. the intrinsic part of the job is the same sketch: clay, casts, production. and I still love the thrill, I still love the challenge of that. every day I love the problem solving. so in my days, I think now as senior designer the key of it is problem solving. I think in the past, you sketch areas of the car, but now I can move around and help people with different issues they’ve got on the products. and say, ‘okay, yeah we can fix this by changing this line,‘ or the other one could be, ‘okay, we use this material,’ or ‘we need to try this concept’ or ‘go and try a new supplier to find the solution for this.’ I think I really enjoy that – puzzles every day. like a new fresh challenge every day. and the technology is always changing so you need to stay up to speed with the technologies and the innovations in the industry to make sure we’re getting the best mechanics in the McLaren which need to be cutting edge.

McLaren special operation 650s spider

DB: how do elements from formula one, such as aerodynamics, directly influence the designs of McLaren vehicles?

RM: aerodynamics have never changed. so with McLaren, we can’t just follow the trend, we have to follow the function. and that means, a radius that cut through the air a 1000 years ago, slices the air the same way. if you look at super car design over the last 50 to 60 years , where porsche and aston martin have had very beautiful cars – clean fuselage body sides. so with McLaren as the new kid on the block, it wasn’t just to be different for different sake, but it was really to find the reasons on why a form of car tells the story of its function – the same way formula one cars do – you can see where the air is divided, where the air goes into a scoop, a different radii to attach the air, or separate the air – it has its own intrinsic language which you can understand without anybody actually walking you around the car, if you take the time to look at it. and that’s what we look for the road cars to do, they need to do that job.

in a show room, if there was no salesman there, the idea is that as a customer, you can walk around the car, and you can work out – OK the air goes in here, it goes through a hidden duct on the sill. its like a living thing, like bio-mimicry, the archways, the airways of the car – we just happened to have packaged some people inside – we see it like a living thing, the active aerodynamics. you can see in the future the target is clearly like transformer cars, cars that adapt and adjust to the requirements of the racetrack or the road. it gives you the optimum in almost every situation. McLaren is definitely about breadth in ability across all the products, certainly in each individual class or segment. we need to be the fastest around the track, the most adaptable in terms of everyday usage. obviously correct materials for the correct function.

traditionally in car design you look for what the latest trend is – whether if its through the pressing of the materials, you may be able to get really sharp creases nowadays. but for us, we don’t need to do that. we only do sharp crease where we need to separate the air, not a sharp crease because it shows we have the latest stamping technology. we do what’s correct for the function of the vehicle. and what makes it really interesting for us as a designer as a challenge, is when you have to mix the two together. so a fender line, or a body sideline, is not there just purely for proportional reasons, it also has to serve a double function – so the second function is, that line needs to split the air in a certain way, or it divides the air – it helps tells a story of the airflow so the customer can see it – and that’s where we stand out against the competition.

DB: what development process would you say takes longest to refine?

RM: I think the aspects of the design that take longest to develop on the McLaren’s are from the vehicle architecture side. they obviously need to be done years in advance, we need to obviously plan and look to what the future opportunities are, and what the brand needs to be able to do, and how it can grow in the future – how we stretch the brand. so we’ve got the core values, the secondary values and the tertiary values, and how they spread out, and which products can stretch and which ones needs to stay pure to the brand. so the architecture is something that is constantly being worked on.

the other thing that probably takes the longest time is the aerodynamics, because, you do the sketches, then we’ll go into the clay, then we do some early cast surfaces, then we need to feed those surfaces into the aero guys, and once they get those, they can do some computational, fluid dynamics. but beyond that point, they really need to get into the physical side, so we go a risk through the early part of the project because the computer is never really as good as reality. so we go to a point where we know we are working within a bandwidth which is what we can deliver – so we have a level of safety. but beyond that, when you get into the real world inevitably certain things change, and it’s how the risk is, or the aspect that takes longer due to its risk to develop, is then the loops with the aerodynamics, whether its the thermal, because our cars are using turbochargers, so they generate a lot of heat – so how do we cool this engine.

we’ve got lots of openings on the car, a lot of meshes, and obviously you need the car to look nice and sleek, or the products need to be more open to visually communicate the power, the kind of lightweight-ness. so its trying to find those kind of tricks. anyway, this feedback with aero, sometimes it can be the diffuser that completely needs to change shape, because its not just there for just aesthetic reasons on a McLaren, obviously they need to create like 300 kilos of downforce or 150 kilos of downforce, whether that’s the rear diffusers or the front diffusers. certainly the challenge is the heat exit over the engines and out of the back car, which with the P1 you can see – which is why it has this kind of completely chopped away rear end with the mesh, very open, very le mans like, but fluid in its silhouette, which is very McLaren, very formula one. so yeah, aerodynamics is also key, the one with the longest risk, if you may.

DB: how would you define innovation?

RM: so my definition of innovation, it’s a tricky one, but I think for me it’s more of a philosophy on innovation and philosophy to me is something which constantly needs to change, evolve, and adapt. that’s what philosophy is, something that’s constantly changing, innovation is constantly changing, materials, technology is constantly changing. all sorts of cutting edge, constantly changing. so for me, McLaren has a philosophy on innovation and that is just to stay at the forefront, and that’s through research, suppliers, reading science journals, making sure there are the correct people on the design team or we hire the correct people who have a passion for finding new technologies and not just relying on looking at, ‘okay, this is the latest trend.’ we need people to be looking at the future, what’s next, nanotechnology, or what’s the next lightweight material, or the next laminated combination of materials. so yeah, philosophy on innovation, if that’s good enough for you.

DB: what’s the best piece of advice you’ve ever been given?

RM: you don’t get if you don’t ask. and I think that’s been good from pushing for career opportunities through to certainly design-wise day to day. you need to change a line, you need to change an element or position of the package so you can get the best sense line or the best proportion or the best corners and stance. and of course you need to go and ask. because you can’t sit there and moan or ‘ah, I wish I could do this.’ you just need to go find the guy, get the guys together you need to get the information from. you ask them and make sure you get it hopefully. but that’s you don’t get it if you don’t ask.

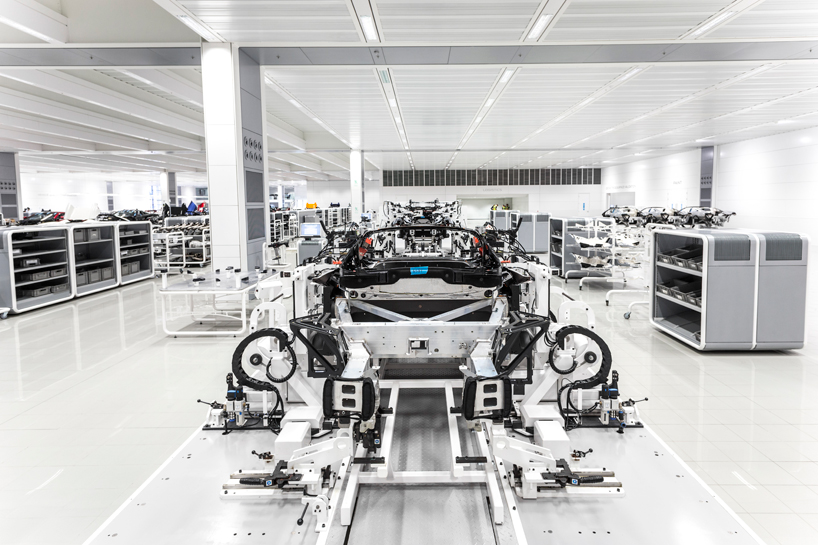

stay tuned for the final part of this three part series, as designboom will cover an overview of the P1 and 650s manufacturing at the McLaren production centre, and tour of the McLaren technology centre.

about McLaren automotive:

founded in 1989 as McLaren cars to produce the F1 supercar, the company is now making a major step forward with ambitious plans to produce a range of high performance sports cars.

building on the huge critical success of the McLaren f1 (1993-98), and the sales success of the mercedes-benz SLR McLaren (2003-09), both of which have pioneered carbon composite body technology and active aerodynamics, the new company is preparing to introduce ground-breaking levels of technology and performance in a more affordable category of the sports car market. beginning with the McLaren MP4-12C in 2011.

a bespoke production facility, the McLaren production centre (MPC) is planned for the MTC site that will enable ultimate production of up to 20 McLaren sports cars a day and support over 800 direct jobs and an estimated additional 1,500 indirectly in the local economy. planning permission for the MPC was granted in august ’09. the first in the new range of McLaren cars – the 12C, a high performance and technically-advanced two-seat sports car – will be delivered to customers worldwide from 2011 through a dedicated McLaren dealer network.

the SLR range, McLaren automotive’s most recent product, has proven the company’s ability to combine hand-built high-quality production techniques by highly-skilled technicians to volume car production lean manufacturing processes for ultimate efficiency. these manufacturing techniques, unburdened by the clutter of airlines and other traditional automotive workshop equipment, will be employed for 12C production ensuring that the new range of McLaren models will be built in a similarly clean, calm and efficient environment.

the MTC allows the whole car launch team – design, development, engineering, purchasing, testing, production, marketing, sales and aftersales – to be fully integrated within a few meters of each other. potential customers are, today, able to see the formula 1 workshops alongside the existing SLR stirling moss production line and understand for themselves that the link between the road and race cars is tangible and visible.

paul howes, head of exterior design McLaren gives robert melville a big hug outside the HQ in woking

image © designboom

concours d’elegance (20)

mclaren (54)

PRODUCT LIBRARY

a diverse digital database that acts as a valuable guide in gaining insight and information about a product directly from the manufacturer, and serves as a rich reference point in developing a project or scheme.