interview with IDEO’s paul bennett on designing for the end-of-life experience

all images courtesy of IDEO

paul bennett is the chief creative officer of IDEO. apart from working alongside clients and colleagues on human-centric and socially significant products, services, and experiences, bennett has created IDEO’s largest global practice — consumer experience design — ran its san francisco office, established its new york office and grown the firm’s business in europe. bennett provides creative leadership on an extended scale by traveling, learning, and working across the globe.

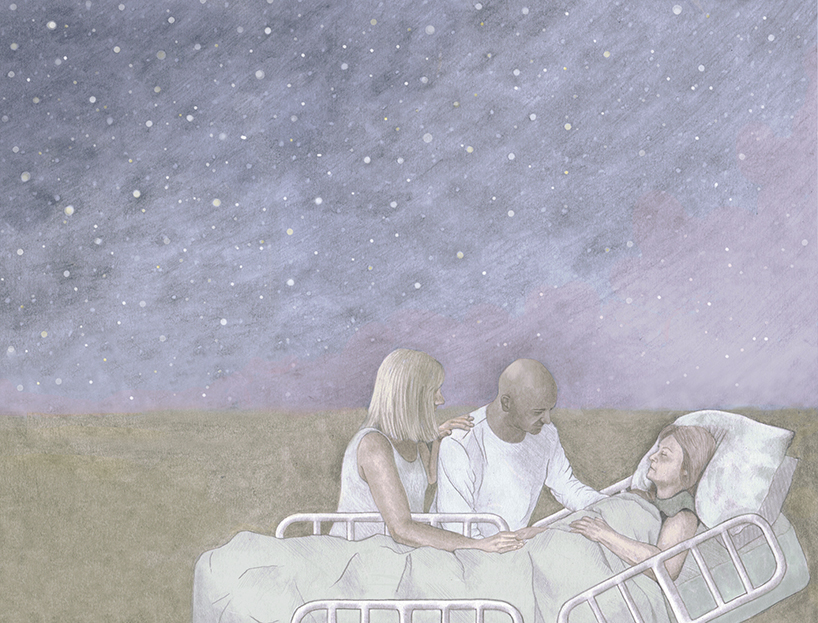

recently, bennett became an active leader in the ideation of a new openIDEO challenge that focuses on an intriguing and often overlooked topic: how might we reimagine the end-of-life experience for ourselves and our loved ones? calling the global community to action, the ‘end-of-life’ challenge asks for ways in which this process can be made more human-centered, and solutions on how people can prepare for, share and live through the final chapter of our story.

we spoke with paul bennett about how he was originally introduced to IDEO, his personal relationship to the ‘end-of-life’ experience, and the conversations he hopes the openIDEO challenge might yield.

designboom: can you tell us the story of how you came to work at IDEO?

paul bennett: 15 years ago I had just left my own brand consulting business in new york and was looking for the next thing to do. to be completely honest, I was somewhat frustrated by the world of brand and its reliance on buzzwords, jargon and frameworks. I wanted to get back to making things with my hands. I was reading an article in a new design magazine that my partner jim, a photographer, had shot a story in, and there was a piece about this place called IDEO.

the story explained that the company was expanding past the world of product design and their new CEO, this guy called tim brown, was talking about how he saw them doing that. I’d never heard of either of them but it said that tim looked like russell crowe, which piqued my interest. I wrote to him and said: ‘what you’re doing sounds cool. can I come and meet you?’ the following week I came in and met tim, we talked for over three hours, two hours longer than we had planned, and I knew this was the place I wanted to work. I started in palo alto four weeks later. tim has gone on record as saying that I was the most impulsive decision he has ever made. but here I am fifteen years later, and I hope both IDEO and I have changed each other for the better.

DB: how were you originally introduced to the world of design?

PB: I was always making stuff as a kid. I was a crafty, shy billy elliot twirling little gay boy who grew up in the north-east of england. my dad bought me a craft magazine called the golden hands encyclopedia of crafts, which was chock-full of art projects from the 70s – knitting, macramé and tie-dye – which I voraciously plowed through and did. I still have bunch of the stuff, it’s pretty funny. it wasn’t until I was in my teens that I realized that people could make a living through doing ‘arty things,’ so I worked hard, made good grades, got into art school and eventually became a graphic designer. but it was the idea of making that has stuck with me all these years. I still craft and make, it’s a core part of who I am.

DB: can you describe your role and responsibilities as chief creative officer at IDEO?

PB: it’s certainly not about being more creative than anyone else: in fact I’m in constant awe of the things people here are capable of. I guess it’s two things: first, it’s an exploratory role — I look for new things, places, ideas, clients and domains that we can go into. I’m constantly looking, traveling and exploring the world to see where design can make a difference. secondly, it’s a coaching role: enabling and hopefully inspiring our designers to go on that journey with me. I don’t really need to quality control or police what we do. in fact, it’s much more about being a good role model and providing as much buoyancy as possible for people.

DB: what do you consider to be some of the existing problems with the current end-of-life experience?

PB: tricky question. obviously, it’s a deeply complex social, medical and cultural ecosystem with many, many good people doing what they feel is right. I fully accept my naïveté here, but that ability to see opportunity in dark things is a hallmark of the design profession in my opinion. we’re relentless optimists. to be completely frank, I was asked recently what made me a ‘death expert’ and what came out of my mouth was the truth: ‘my dad died.’ on that level, we’re all experts. my father, who meant everything to me and who gave me my creative start in life, was diagnosed with terminal cancer. watching him struggle to maintain his dignity throughout the tremendous battle he had, watching my mother deal with it, being both apart from it and connected to it myself — all the pieces of that were tough. every conversation, decision and intervention was fraught because we had no context for any of it, no way to navigate, no guide, rule book, tools or precedents. I remember not knowing how to get a nice tombstone for my dad, or what to do at his funeral. we struggled to talk about it until it was almost too late, but it was my last call with my father, when he knew he was going to die, that struck me as the opportunity. I was in california and he was in the UK, and he knew the end was coming. I told him I was getting on a plane and he said: ‘don’t. I don’t want you to see me like this.’ that recognition, acceptance and understanding was universal, and somehow my father accepting it, has allowed me to see death as a design opportunity. an opportunity where, if we remember the person in the center, our family member, our friend, yourself, feels like a huge opportunity to shift how we talk about, plan for, enter and ultimately leave our lives and stay in the lives of those we leave behind. it’s a massive design opportunity.

DB: why was it decided to introduce this theme to the global openIDEO community?

PB: it sort of decided itself. IDEO has an interesting ‘manifest destiny’ approach to our future: if we believe in something passionately we say it out loud but allow others to influence and build on our idea, and we see what sticks. I have certainly never professed to have an ‘answer’ to the end of life, but I felt it was an interesting question — can we as designers, affect change here and can death be redesigned? a magazine covered the topic and our interest in it, and the world answered. I’m not exaggerating, I have never seen such a response to a question — hundreds of people have contacted me, all of them wanting to tell me their story, their experience, to share, talk and help. many had ideas for things to shift different parts of the system, the ways in which they were trying to create workarounds already. that is a core part of our process: to recognize that when people are creating their own solutions to a problem there is an opportunity. we had wanted to bring this topic to openIDEO for a while in order to engage as many people as possible in the process of designing solutions. we searched for the right partners who were prepared and brave enough to not just fund, but to actually implement the ideas. it’s critical that we get this conversation off the drawing board and into the world, so we found two great clients in sutter health and helix centre and here we are.

DB: how has it been received by designers and contributors thus far?

PB: pretty amazing, actually — and we are only at the beginning of the challenge. we hope many more people will participate. there’s a wellspring of ideas out there, from simple to systemic, and right across the journey. different cultures see death very differently, that has definitely come to the surface. in europe and the US for example, death is moribund and almost victorian — where the shades are drawn and the candles are dimmed, so to speak. whereas in asia, death is accepted, celebrated, and even in some cases, seen as joyful. one theme that seems to be resonating is to find ways to make death more ‘normal,’ not this terrifying void that we fear our whole lives but a natural part of our lives, one that we are OK with, accept and plan towards rather than avoid and run away from. again another topic that a lot of people are interested in is getting kids more comfortable with death, not sheltering them or hiding it from them, so that they see it as a natural part of life and not something that they grow up fearing.

interestingly, a lot of people have been expressing gratitude. there have been a lot of ‘thank yous’– both for hosting the challenge and to individuals for sharing their personal stories within it. I think it’s quite unique because in most openIDEO challenges, we’re solving for the needs of a particular group of people. with the end of life challenge, we’re solving for ourselves and our loved ones. for this topic, our community is imagining solutions that they might possibly live out. when we ask the openIDEO community, ‘what are the needs of who you’re designing for?’ they can turn to their own personal reflections. there have been more personal stories shared than ever. we typically see a lot of research articles in our inspiration phases, but this topic has resulted in an outpouring of genuine and personal sharing. I’m glad that my story has inspired others to tell their own.

DB: what solutions do you hope the ‘end-of-life’ challenge might yield; what conversations do you hope it might spark?

PB: we’re starting to see seven big themes cluster out of the first round of inspirations. I’d love people reading this to engage in this conversation with us and build on them, make them concrete and actionable. so far we have:

connectedness — to friends, family, nature and beyond – is a critical part of living. what might connectedness mean in our final moments? what existing connections might we want to deepen and enrich? what unexpected connections might be newly relevant? alternatively, what connections might we want to let go of in our final moments?

new values — rituals, customs and cultural values ground us in life. they’re typically passed down from generation to generation. how are these changing or evolving, influenced by younger generations and their unique, digitally-native perspectives on death? how is the culture of death evolving for the next generation

what surrounds us — whether death happens at home, or more commonly, in hospitals and institutions, we’re curious about the impact that physical and sensorial experiences, materials and objects can have on the end of life. what are tangible ways we might create new sensory experiences for patients – touch, taste, smell, sound, sight? how might we enrich the dying experience in whatever physical setting it occurs, so as to honor our personhoods?

(continued) planning now — fear or despair felt at the end-of-life is only heightened by the fear that our death might burden the people we love. if we are lucky enough to be able to plan for our final moments, how might we better prepare? this opportunity area also focuses on accessibility of planning resources. how might we allow people from all socioeconomic levels to plan in a meaningful way?

services & care — the end-of-life experience is part of a deeply complex social, medical and cultural ecosystem. there’s a massive need for both clinical and social services to support this ecosystem, as well as the policy and training to suit the significance of these last moments. these underlying supports and services play an absolutely critical role in our, and our loved ones, experiences with death.

the cost of dying — we do our best to financially plan for important things in life: a wedding, an education, a house – how does dying fit into this equation? here are a few quick stats to set the stage: 25% of seniors lose all their assets in the last five years of life due to the costs of advanced care. that number jumps to 41% if you don’t take into consideration housing. a caregiver over the age of 50 will lose $300k in wages and benefits in the caring for their loved one. the financial aspect of dying is underdiscussed, yet plays a critical role in suffering and a person’s legacy. we’re remembered by the stories we leave behind – who we were, how we lived and loved – and by what we leave on for the next generation.

after death — after we go, we continue to have impact on people’s lives – we don’t exist in isolation. how might we remember those who have died and incorporate them into our lives? how does that person continue to connect to communities? for many of us, our heritage is rooted in tradition and remembrance – how might we incorporate that into the way we – and our loved ones– are remembered?

looking through this, I never thought I’d say this about death, but it’s really a very life-affirming subject. I hope my dad is watching somewhere.

DB: where do you see design, in general, heading in the next 5-10 years?

PB: I want design to be fearless. go into the tough spaces and find the light: death, mental illness, poverty, inequality, education, government, citizenship, healthcare, food. I don’t want to just change the conversation, but also make the outcome both beautiful and meaningful. I think we’re on a course towards that, and I want to see design really step up to the plate. we are certainly seeing evidence in our own business that taking a more impact-driven approach to our work has simultaneously shifted our client base and motivated our designers to go further and aim higher.

DB: what is the best piece of advice you have ever been given?

PB: listen more. I think I do.