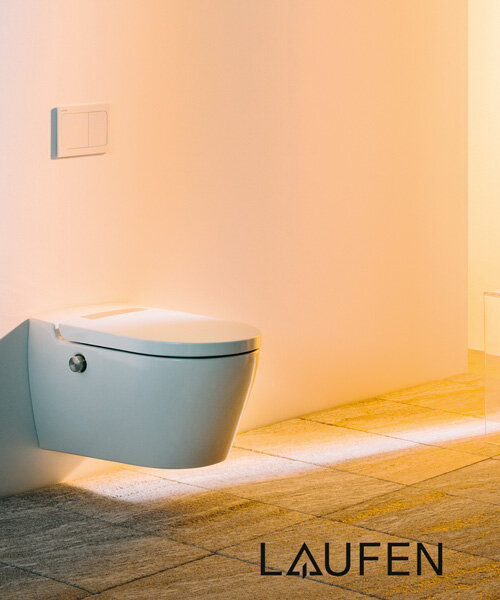

on october 17, 2020, triennale milano opened a retrospective dedicated to enzo mari, one of italy’s greatest masters and theorists of design. curated by hans ulrich obrist, in collaboration with francesca giacomelli, the show is a survey of mari’s activity and comprises over 250 projects. the exhibition consists of a historical section and a series of contributions from international artists and designers. nineteen research platforms, created especially for the triennale exhibition, give insight into the individual projects that have given rise to the key themes of enzo mari’s artistic vision and practice.

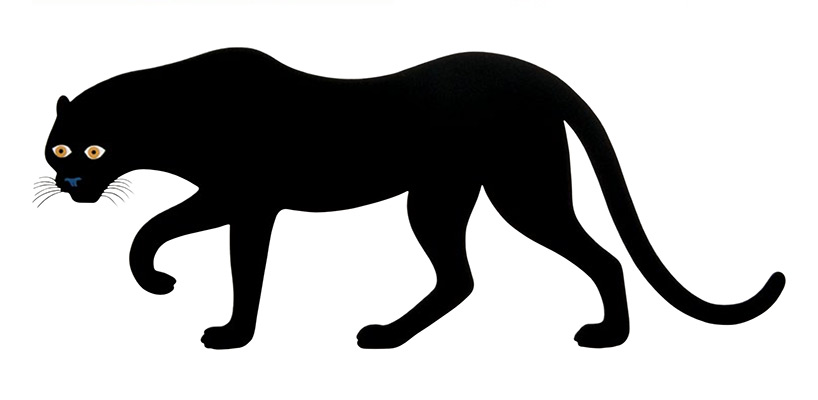

‘16 animali‘ wooden puzzle, enzo mari for danese, 1957

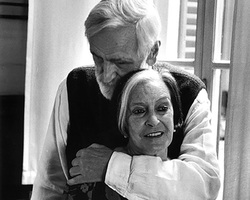

designboom* sat down with hans ulrich obrist, who invited us to witness the process behind the curation of the show at triennale milano. *in the eighties, both founders of designboom have been enzo mari’s students, while our editor-in-chief, birgit lohmann, later collaborated with him on several design projects, over 20 years. when she formulated the questions below, she could not take into account that enzo mari died the day after the opening and that his wife, the writer, art critic and curator lea vergine, passed away the following day. apparently both deaths were caused from complications related to COVID-19.

‘16 animali‘ wooden puzzle, enzo mari for danese, 1957

exhibition views © designboom, main image © gianluca di ioia

(shortly before her death) nanda vigo created a light installation for the exhibition entrance that has never been shown previously. neon signs reinterpret ‘16 animali‘ and ‘16 pesci‘, two of mari’s most famous works. display design by paolo ulian.

‘specosfera‘, enzo mari 1965

DESIGNBOOM (DB): when was the last time you had a conversation with enzo mari? do you remember the subject?

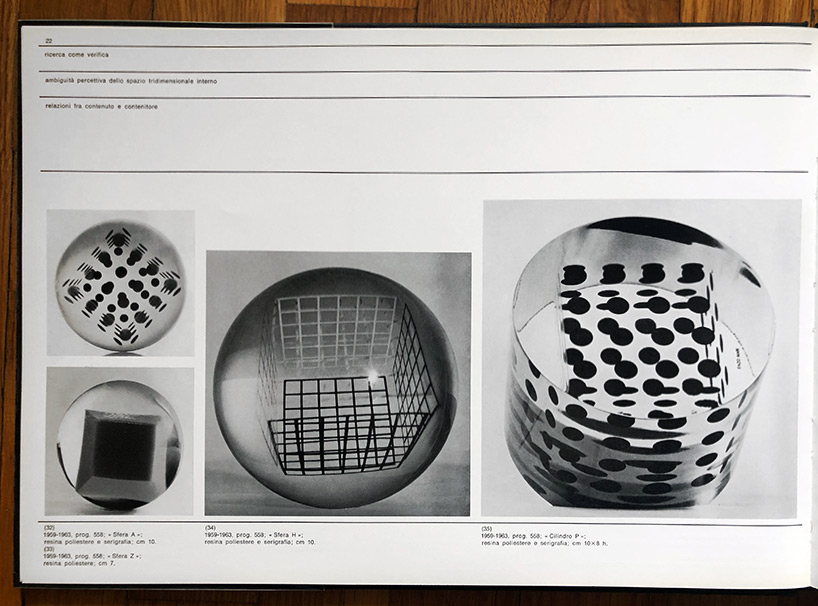

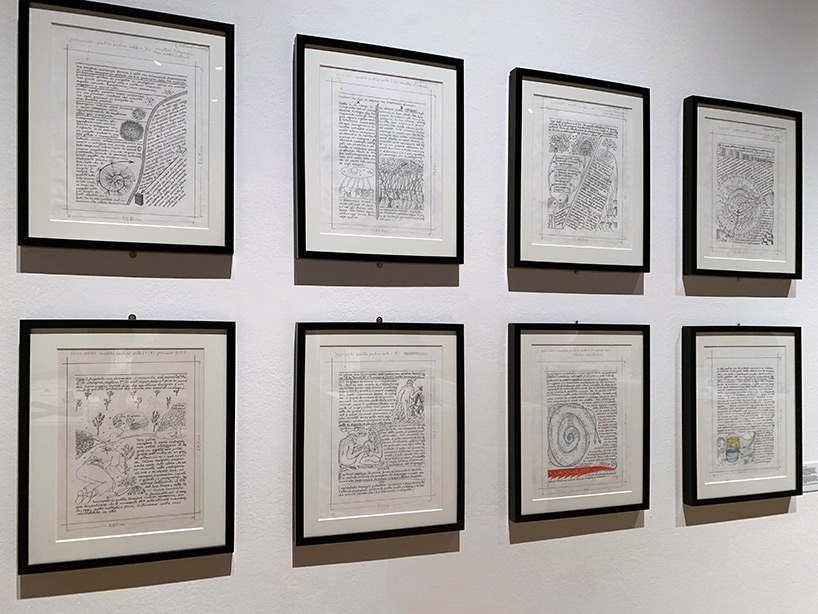

HANS ULRICH OBRIST (HUO): I remember it precisely, actually. I can show you because I actually have a book. it’s one of my favorite books of all times. it’s a horizontal book called, ‘la funzione della ricerca estetica’ – the function of aesthetic research. he signed it with the date — 3rd of february of 2019. that was our last encounter, one year and a half ago. the book is designed by mari in a very special way, because you have these three lines always on top and the grid underneath. a very beautiful design. the amazing thing is that already in 1970, he had created the work of a lifetime.

enzo has had many lives. he has been so productive. there are his book designs, calendars, his industrial designs (including furniture), toys for children…artworks, and works for public spaces. then there are his teachings, his manifestos, his polemics. I don’t know how old he was in 1970, but he was in his 40s, so it’s quite extraordinary (editor’s note: he was 37).

a page from the book ‘la funzione della ricerca estetica’ by enzo mari, edizioni di comunità, milano, 1970

designboom’s collection, image © designboom

HUO: when we looked at this book together (as I finally found a copy, it’s very rare) I did an interview with him about it and he explained the different pages…yes, that was the last interview. just a few months earlier, when stefano boeri and I visited him, he made his announcement that he would donate the archive to the city of milano, but that it should not be accessible for the next 40 years.

a page from the book ‘la funzione della ricerca estetica’ by enzo mari, edizioni di comunità, milano, 1970

designboom’s collection, image © designboom

HUO: it’s possible that we all somehow have enzo mari influences. we at the serpentine in london run a gallery, a ‘kunsthalle’, a public art gallery. we work with architects on our pavilions, but we also regularly invite designers to do exhibitions — martino gamper, konstantin grcic, this year formafantasma. whenever we invite designers, I ask them who their inspiration is and it’s always enzo mari. formafantasma are of a younger generation than martino and konstantin. it continues generation after generation. his influence is enormous. he is the most influential designer of our time. so that’s a whole other aspect. I think he’s kind of the leonardo da vinci of our time. it’s really almost a renaissance ‘thing’.

‘44 valutazioni‘, (’44 evaluations’ that ricompose would create the sickle and hammer motif), 1977

HUO: he was, of course, very antagonistic to the design world. I remember my very first encounter with him must have been probably around 1997 or 1998. I had met stefano boeri in the mid 90s and spent a lot of time in boeri’s home and he would always organize these amazing dinners, epic dinners with ettore sottsass, enzo mari, vico magistretti, cini boeri, achille castiglioni, nanda vigo…we had amazing encounters with this generation of italian designers, who emerged in the 50s and 60s. all these legends in a single room. stefano sat me next to mari so I spent most of the evening talking with him. he started to scream really loudly about the design world. he was very upset, he said, ‘we need to get rid of the idea of profit, we need to get rid of the idea of commercialization, of brands, of advertising. and we need not only a democratization of design, but we need design to communicate knowledge.’ I was very touched by this incredible manifesto, in fact, the whole evening became a manifesto. he spoke endlessly, simply would not stop. so I asked, ‘can I do a studio visit?’ that’s how I got to know him. we continued a very friendly dialogue over many years. whenever I was in milan, I would try to go see him. I started to do a lot of exhibitions, and he was in my show ‘utopia station’ and of course, utopia has always been at the core of the mari constellation (as stefano boeri used to say).

HUO: I just came across another wonderful publication from 1971, which I also studied preparing the show — it’s called ‘notiziario arte contemporanea’, edizione dedalo’. the sales price was 400 lira (three euro) and inside you can find ‘52 interventi sulla proposta di comportamento di enzo mari,’ curated by the amazing, the one and only, lea vergine (editor’s note: lea vergine became his wife. she has been a writer, art critic and curator). mari’s proposal here is to ‘enunciare la propria visione utopizante dello sviluppo della società. definire la strategia che si ritiene utile per questa utopizazione. dire in quale momento tattico di questa strategia sia collocare il lavoro di ricerca trattato in tale momento tattico. comunicare il lavoro in questione tenendo ben presente che va riferito ai conti precedenti.’ (enunciate his utopian vision of the development of society. define the strategy that is considered useful for this utopization. to say in which tactical moment of this strategy is to place the research work treated in that tactical moment. communicate the work in question, keeping well in mind that it should refer to previous accounts.)

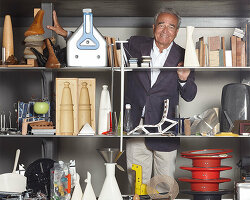

‘intellectual work’, enzo mari’s paperweight collection, first shown at the kaleidoscope gallery in milan in 2010.

mari brought together 66 of his personal collection of paperweights, objets trouvé gathered over the course of a life, that he considered paradigmatic of his own practice.

HUO: this idea of utopia was always present. I invited him to ‘utopia station’ in munich and then of course to ‘do it’, my project of instructions without manuals. I invited him because of his DIY design, his ‘autoprogettazione’ from ’74 that was a great inspiration for my ‘do it’ project. when we did a project with martino gamper at the serpentine, martino decided to show all of mari’s paperweights. it was an amazing collection and display. I wanted to include it in the exhibition.

HUO: I suppose the reason why he was so comfortable with me is that I was in the art world, not part of the design world. he was a bit similar to cedric price (I say this because I was also quite close to cedric price)… and cedric price was also a great rebel, who was very antagonistic to the architecture world. mari is in a way, a cedric price, because they’re both rebels within their own field. mari liked invitations to join what is happening in the art world, because, in a way, that’s where he started. he began with artworks, exhibitions, arte programmata. we went to lisbon for the design biennale of guta moura guedes and did a talk there. then to ‘utopia station’ in venice and munich, then traveled for ‘do it’…many journeys with him. that’s really the root of this exhibition, it’s the time I spent with him.

DB: was enzo mari personally involved in this exhibition?

HUO: yes, absolutely. the exhibition has been the outcome of 20 years of friendship. during my very close dialogues with stefano (boeri), on one day he said, ‘I’ve been appointed president of the triennale and I want to do a show with mari and with you.’ it was one of the first things announced. I was excited because this was an unrealized project of mine (one of my many unrealized projects). in the last two or three years, he was not talking so much anymore, but he agreed to do the exhibition and was also involved in it. lea vergine was essential for the process; francesca giacomelli as well, because she had already worked with enzo on his GAM exhibition in 2008 in turin. I went to see the show at the time, and I love the way he brought out hundreds of objects into display. this was the last show enzo was designing — actively involved. so we (me and stefano) suggested that we could take that as a starting point. he liked this idea, we told him we would also have some new sections around it.

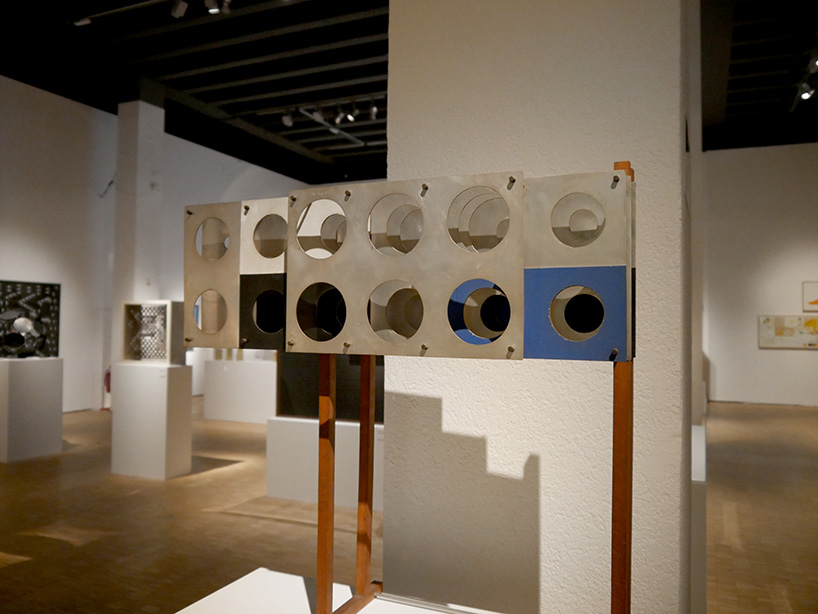

‘modulo 856’, enzo mari, 1967

device to test the reactions of a contemporary art exhibition viewer

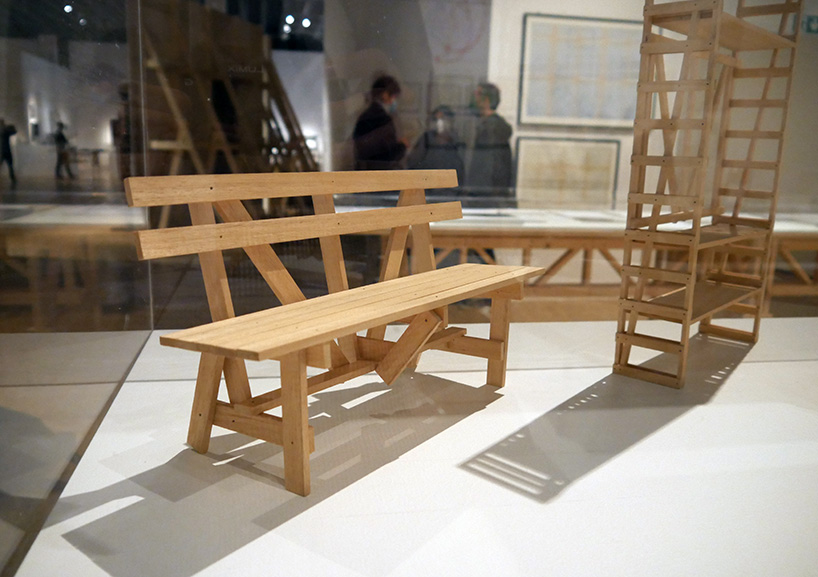

HUO: for mari, design is of course, always about form. he is a rebel with an obsession for form, for the transformation of form. for him, it’s always about the production of knowledge. he creates through these forms a model of a different society. so for him, it’s always political. if you look at the ‘autoprogettazione’ from 1974, he always said that it’s about communicating knowledge. we wanted to show these research platforms, not only his objects, but also their process, how he got there.

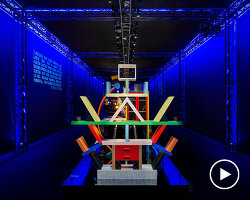

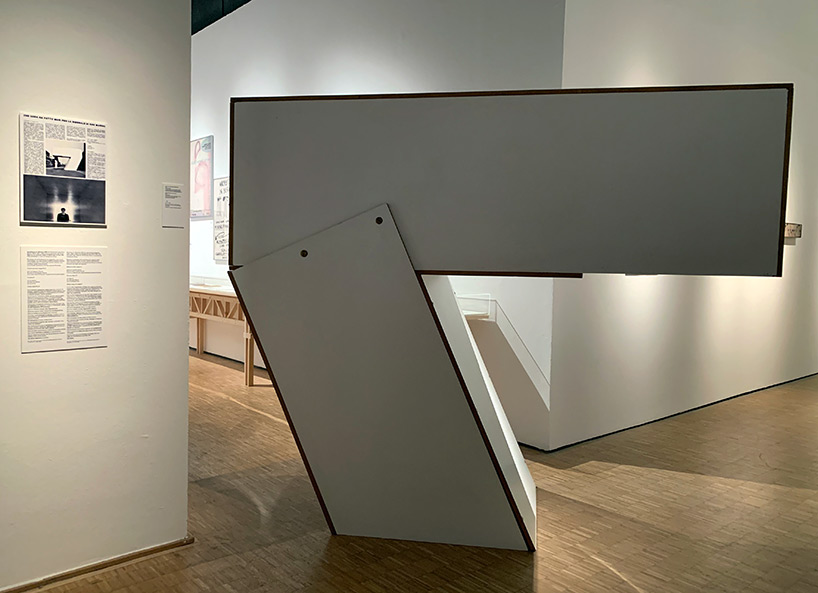

exhibition design for ‘vodun’ african voodoo, originally for the fondation cartier show in paris, 2011

image © gianluca di ioia

‘autoprogettazione’ chair, 1974; re-edition for artek in 2010

HUO: it’s nearly impossible to do a survey of enzo mari, because he did more than 2,000 projects in his life, and as we discussed, there are so many dimensions to each. therefore we thought we needed different sections, different entry points. we helped the viewer to have different possibilities to enter in his world…because mari is a world or as (stefano) boeri says, a ‘costellazione’ / constellation.

‘autoprogettazione’ small scale models

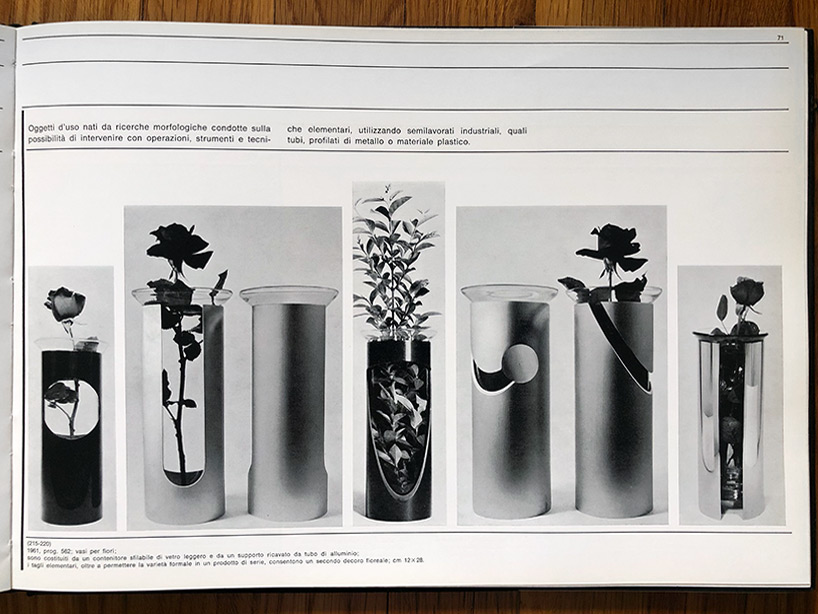

HUO: in the historical section, inspired by the GAM exhibition in turin, you can see all these important series from his paintings in the 50s to the sculptures, structures. from ‘arte programmata’ in the 60s, to the nature series, to the vases, to his exhibition designs, to the ‘autoprogettazione’, all the way over the ‘44 valutazioni’, to the ‘tre piazze del duomo’ (three public squares in milan), to his project of a design museum, to the ‘lezioni di disegno’, to his teachings — you can sort of see all these projects, and then you can dive into the research platform and see the process.

HUO: freely interpreting the historian erwin panofsky, we can say that the future is invented with fragments from the past. so we invited several contemporary artists and designers to give an entry to mari’s world by picking something they like. the ‘autoprograttazione’ is the most inspiring piece for a lot of younger artists. I think it has to do with the fact that it’s so democratic that in a way it has to do with the do-it–yourself logic. visitors can assemble a 1000-piece puzzle created by rirkrit tiravanija on a chrome plated steel. in a sense, ‘autoprogettazione’ becomes a puzzle.

HUO: danh vō has been doing many exhibitions and projects related to mari. he combined the austerity of enzo mari with the danish designer nanna ditzel, and created a kind of a hybrid. then you have the very political interpretation of the youngest participant, dozie kanu. dozie, of course, has been interested in politicizing also the ‘autoprogettazione’, not only through its democratization of design. it is a provocative alternative to the capitalist model of mass consumption. kanu combined this idea with the electric chair, and how many african americans (as kanu says) die through this execution. and so, he talks about this hostile system and particularly the execution of george stinney in south carolina, as a case. three different readings of the very politically charged ‘autoprogettazione’ project.

exhibition view with enzo mari’s ‘allegoria della morte‘ installation, originally from 1987

‘allegoria della morte’/ death allegory

HUO: dominique gonzalez-foerster wrote a long letter, which the visitors can take away. the letter talks about the many collaborations of enzo with iela mari (editor’s note: his first wife), among them the ‘gioco delle favole’ / fairytale game. then you have also tacita dean (who, as you know often makes tribute to pioneering figures like cy twombly, a homage to mario merz. she makes these homages to artists she’s inspired by). she did an homage to enzo by basically saying that she’s sorry that we never got to meet. it’s a very poetic, beautiful temper on a postcard, addressed to enzo directly.

HUO: there is a workshop by adelita husni-bey, a young artist in milan, that goes back to the children’s books; two artists of enzo’s generation: barbara stauffacher solomon (swiss american, inventor of the super graphics). I’ve worked with her before, she’s extraordinary. she seeks always interaction with the exhibition space, so mari’s initials became a gigantic wall painting. there was the idea of making the initials almost into a logo of the show.

‘box’ chair, enzo mari for anonima castelli, 1971

HUO: and then, of course, we have also the interview archive. I have created an edit of five of my interviews with enzo. that’s another entry point for people, in particular for who never met enzo mari. a possibility to encounter the persona, to encounter his incredible cause, his incredible ideas. adrian paci took an extract from that, and did a piece related to reducing the sentences of mari gradually, and he isolates just one question — try to think of god, what god would you like to have? and mari’s answer is, I don’t know.

we also have mimmo jodice, a photographer of enzo’s generation with whom I’ve worked before in naples. he created a portrait of the studio of enzo mari. initially we thought, it could be interesting, that actually visitors to the triennale (of course not in bigger groups, maybe in smaller ones) could visit the actual studio of enzo mari (I’m always interested in the places where the art is being created, the ‘laboratorio’). unfortunately, it was not possible to do that, but we hope that one day the mari studio will be preserved. we wanted to make that statement: how important it is to preserve that place for the future. it would be an incredible loss for milano if the studio one day gets dismantled. we wanted the photographs of mimmo jodice to document his amazing studio, so that in their mind, the visitors can experience it, even if it’s not accessible.

HUO: and last but not least, very sadly, we have nanda vigo, who passed away this year. her last project actually is the previously unexhibited work, which she created a few weeks before her passing for the exhibition: an homage to enzo where she interprets with light, mari’s most famous works — ‘the 16 animals’. she created basically a neon, a luminous light installation for both children and adults. in a way we really want to remember nanda vigo here, because it’s so sad that she can no longer be with us and see this last piece of her.

so it’s many entry points. all of this, the structure of the show, was discussed with enzo when we met him in 2018 and 2019.

DB: why do you think the work of enzo mari is particularly relevant in current times?

HUO: this is a very interesting question. thank you very much for asking this, because I would say that enzo mari is relevant because we live in a society of exacerbated inequality, and in such a society, he refused to design for the luxury industry. instead he wanted to work for the people, to basically do ‘design for everyone’. he’s in that tradition. same for achille castiglioni — I remember I was in his studio and he showed me a light switch he designed: to switch on the light and switch off the light. he said, ‘this object exists in millions of copies, it costs maybe 10 cents, or 50 cents to buy. it’s a great object of design’. he said that’s what the designer should do. it’s designed for everyone. so castiglioni, and enzo mari, are relevant now for really working towards the democratization of design.

‘frate’ table for driade, 1974

HUO: I think another reason why he is so relevant today is because of his understanding of ‘ecology’. we live in a world of extinction, elizabeth kolbert describes it to be the sixth mass extinction — in a way, it’s an environmental catastrophe. one of the reasons is the fact that many industries are now producing objects which last, but they have to get thrown away. you see, and as mario merz once told me (a long time ago), it’s hard to last. it’s of course true for our lives, but it’s also true for objects. very often, if you look at all these technology objects — the iPhones, the smartphone, the screens — they don’t have a live duration of 50 or 100 years, every couple of years, we ‘have to’ change them. enzo mari was vehemently against this. he designed objects to last. I think that is what formafantasma, for example, the great ecology architects and designers from italy (who live in holland), took from him. when they installed their serpentine show, they installed a ‘brancusi tower’ of IKEA chairs — saying, if you buy an IKEA chair, in order for it to have a sustainable, responsible and legitimate use of resources, you would need to use this chair for 90 years — nine, zero. if it’s not used for 90 years, it produces an ecological catastrophe. I think in a way that has a lot to do with enzo mari because it has to do with this idea of his objects. if you look at the exhibition, these objects are very fresh, they are not dated. and you would never throw away a mari calendar or a mari chair or a mari table. it has to do with this idea of the great roman krznaric, on how to be a good ancestor, and his writing is about how to think long term in the short term broad. mari’s importance lies in rupturing the short-termism of the design world. he says we need deep tied humility, we need legacy mindset. we need intergenerational justice, we need cathedral thinking, holistic forecasting and a transcendent goal. I think that is very much what mari covers. he covers all these aspects, and that’s why he is so relevant today.

‘day night’ daybed for driade, 1971

HUO: now, the third point is the idea that in his sort of allegories and in his designs, he very often alludes to the condition of work and to the notion of work as non-alienating. I think we live in a world of artificial intelligence, a lot of work typologies are disappearing, and we need to really consider the importance of work in society. I think that is something enzo mari has always emphasized — his work always wanted to talk about ‘una condizione di lavoro non alienante’/a non-alienating working condition. so, we live in a mari time and that’s why this exhibition is timely for us now. it’s very important to listen to enzo mari. that’s why I hope that this exhibition can, as roman krznaric says, ‘liberate us from the short term thinking’.

DB: if there are important behavioral changes to learn from his body of work, which would be, in your opinion, the most urgent?

HUO: it’s what formafantasma is learning from him, what martino gamper is learning from him. I think we can all learn from him, even the exhibition visitors. mari was always against this idea of consumption, and I really hope that people are not just consuming this exhibition, but that it changes them, and that it leads to an awakening. for this reason, I think it’s a very political exhibition. I’m also very glad that it is going to go into next spring. it will be there for the next salone del mobile in april. I’m very happy about that, because I hope that many people can see the exhibition, and also people of many different generations.

‘quattro, la pantera’ for danese, 1965

HUO: I got to know him well, each of our conversations focused on different subjects — about his design work, his books. he’s an amazing book inventor. exhibitions have always been his medium. he did a lot of exhibitions, for design fairs, for the cartier foundation…actually, we’re very delighted, of course, about this collaboration with the triennale and the fondation cartier because when I was when 20-21, I lived in switzerland, where I went to university, and began my curatorial work. when I was 23, and when I had organized my first show in my kitchen, I received a grant from the fondation cartier. so, I went to france. for me, it was a really groundbreaking experience. the fondation cartier was always very interdisciplinary. when I was 23, I only knew the art world and I wasn’t really familiar with the design- or the fashion- or architecture worlds. through fondation cartier, I met all these people, and it was a big opening in terms of interdisciplinarity. I’m very happy that almost 30 years later, it all came together, thanks to stefano boeri and enzo mari and in milano. I think what’s so interesting is that of course mari has also done displays, not only for his own work, and not only for some of his design clients, but also for museums like the fondation cartier. when they did the voodoo exhibition in 2011, he designed an exhibition for these voodoo figures. we decided to rebuild it for the exhibition at triennale.

‘perchè una mostra di falci’, enzo mari exhibition (originally at danese gallery, milan, 1989)

DB: mari never defined himself as a (professional) designer, but rather as an ideological activist. what in your opinion, is the different approach and execution of these two ways of working?

HUO: I think that he never wanted to be locked, ‘on ferme’, in one aspect of his activities. he, of course, deep-designed objects. he was very much convinced that his objects had a necessity, so he didn’t refuse to design objects even if he was very uncomfortable with the design world. he was very interested in pedagogical activities. we can see that through all the texts he wrote about education, about teaching. I think enzo mari — let’s not forget he began as a visual artist — has always been connected to many different worlds, and didn’t want to be part of just one. if you look at leonardo da vinci, he was a painter, was an inventor, was in the sciences. it’s more that idea. I think enzo mari is not that simple. he doesn’t want just to be a designer, he wants to be many things. this behavior is very relevant for younger creators or practitioners now, because we live in a world of fluid practices. artists who also go into design and into architecture and into music and into literature. enzo anticipated this. it’s about fluidity. you know, if he would say I’m a designer that would be the end of this fluidity, right?