in 2001, japanese brand MUJI started to collaborate with italian artist and designer enzo mari and in 2002 proposed 19 pieces of furniture (which unfortunately did not go into production), followed by workshops. nevertheless, their relationship lasted over years and last year an exhibition for the MUJI atelier initiative: planting the ‘chestnut tree project’ has been shown.

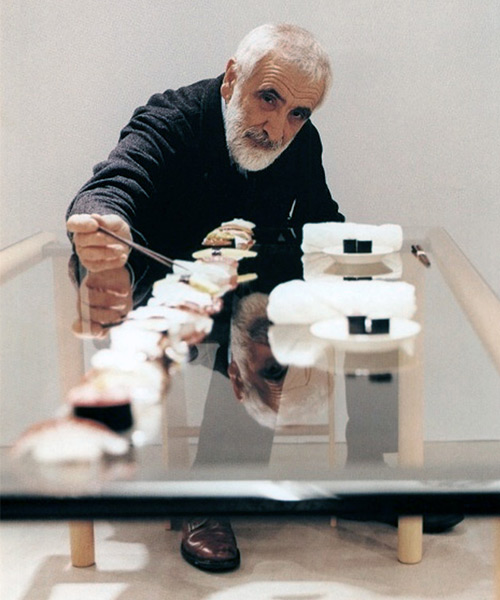

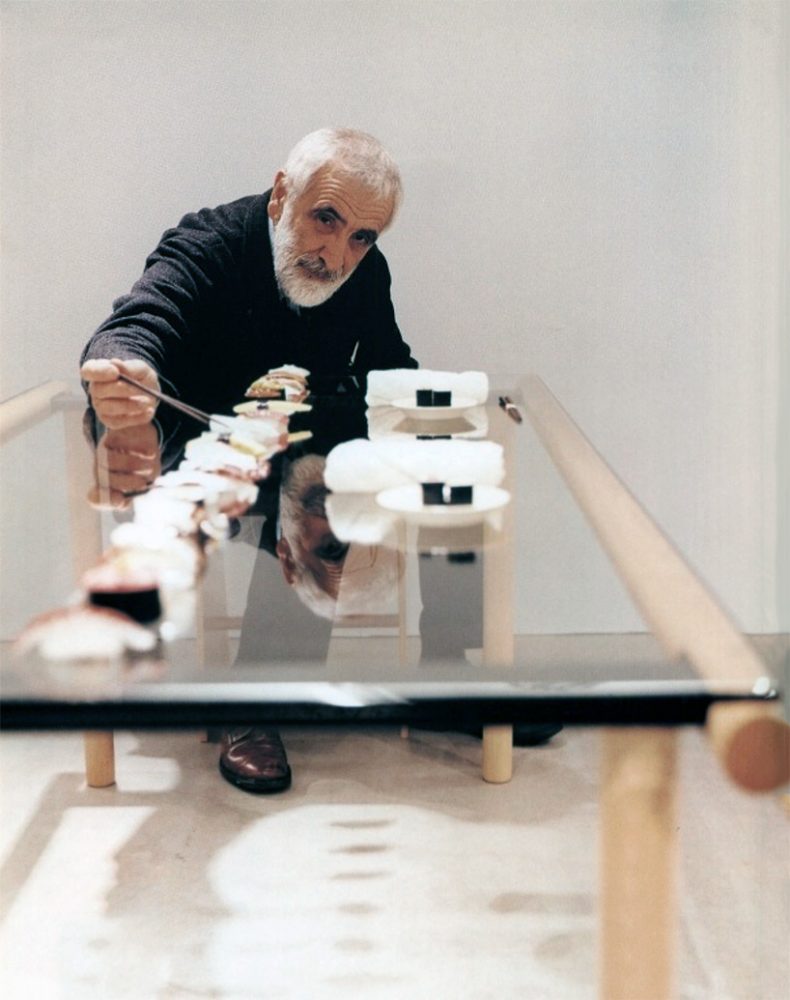

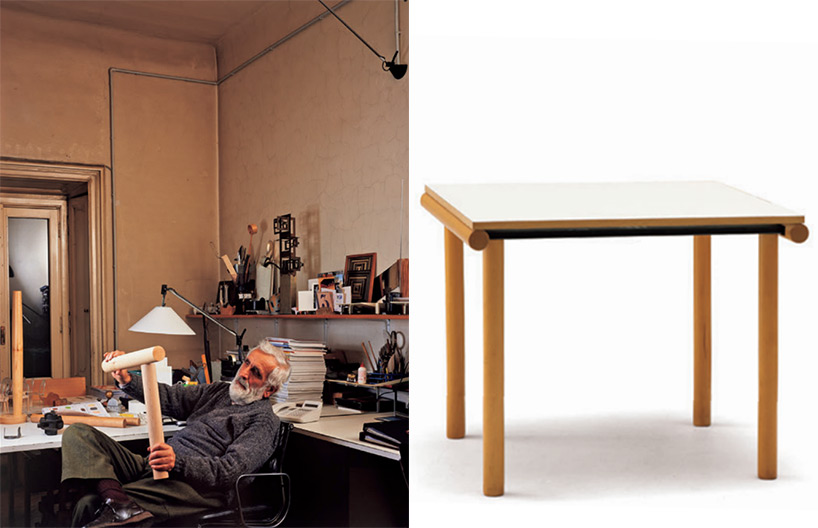

enzo mari and MUJI table with glass top

image courtesy MUJI

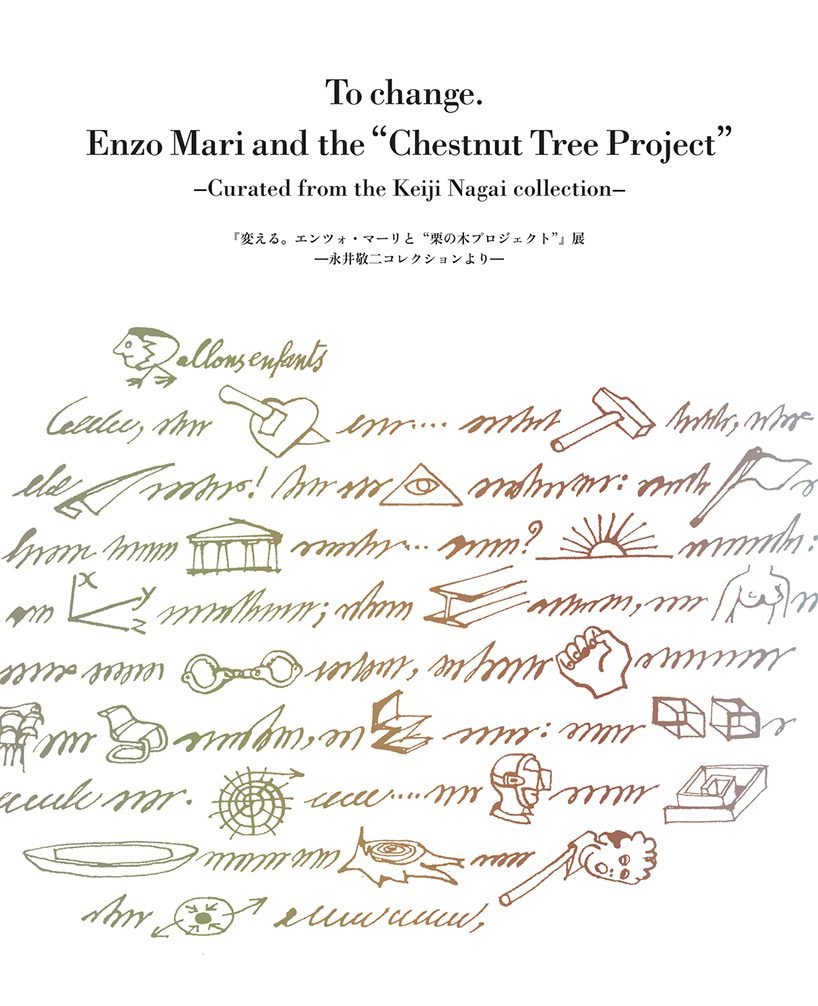

‘in the past, design played a role to invent an outstanding standard in the name of equality. however, following a period of drastic economic growth, it has now been degraded to a simple means to sell merchandise. at present I feel rather ashamed to be a designer. (here) I would like to propose a long-term project to go forward towards the future: it isn’t for financial gain in the short term, but is more like planting chestnut trees to nourish people with their fruit, and to let them relax under their shade. I believe that companies should have this kind of viewpoint’ — introduction by the artist in ‘to change: enzo mari and the chestnut tree project‘, with pieces from the keiji nagai collection.

MUJI agreed, and with this exhibition in tokyo the company introduces the basics of enzo mari’s works to a japanese audience, in order to plant the first chestnut tree. it is his messianic quality that gets people involved in his work. the simplicity of so many of his messages (which are constantly recast into terms that are clear and immediate in their impact) blur the borders between art and design.

enzo mari’s rectangular table with plywood top for MUJI, detail of ‘capitello’/ capital

the capital, in architecture, is the crowning member of a column, and provides a structural support for the horizontal plane, in this case — the table top. only a few of them were made, in form of preproduction prototypes, three of them I acquired for designboom’s studio.

editor’s note:

I have collaborated with enzo mari for over 20 years, and was given by him somehow the responsibility to at least try to document his knowledge he shared with me. ‘birgit, in sympathy, I pass the baton (underlined)’, wrote mari (to me) in may 1987. he told me a lot of times, ‘as a designer (to now come to the point you’re asking me about) – I’m forced to come up with projects that satisfy the needs of an idiot-level man-GOD, a negative man-GOD who has no knowledge of himself or of the real need to affirm himself as what he truly is. I am usually asked to dedicate myself to satisfying the most abject level of needs that people have. I don’t have any way of responding to other levels of needs, which would be needs that neither I nor anyone else could clearly define in the absence of some dialogue. as I look at it, neither I nor anyone else finds himself faced with a group of even ten people who believe in some value that they’d like to see expressed. that’s a conflictual situation.‘

‘what is design?’

‘I don’t know’, he would often say.

not only mari, but other italians who had driven industrial design after the war, have called ‘design’ as ‘progetto’, and ‘designer’ as ‘progettista’. progetto implies to the entire process that leads to a physical form which is the best answer possible for a question. progetto on the other hand, involves many people in different positions, from entrepreneurs and their employees, factories, to craftspeople and even sellers. since other aspects such as materials, technology, machine tools and so on are also complexly intertwined into this process, as a result each situation becomes unique and impossible to repeat. mari didn’t deal with progetto referencing any of his prior knowledge or experience, but tended to work from scratch every single time.’ stated curator keiji nagai.

he has never ceased to direct himself towards a single goal – refusing centerless subjectivity and the promotion of a dignity of work. mari’s work has a consistent philosophy. his idea is to strive for utopia, an ideal which we are to find ‘nowhere.’ enzo mari once said, ‘if we cannot bring about change, it is not a good progetto.’

left: enzo mari demonstrates the ‘capitello’ concept, right: the MUJI beech table, here shown in square size version

image courtesy MUJI

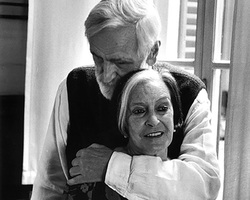

his wife, the art critic lea vergine, summarizes — ‘the central intention of mari’s experiment is to arouse the viewer’s faculties for reflection and critical reaction with respect to his own modes of being and behavior’.

not much of the 19 piece furniture collection has been documented (and designboom has ‘lost’ the related article published in 2002, due to a radical change of our publishing platform. unfortunately, when we switched to work on wordpress, most of our historic archive material got ‘dismantled’). these are chairs enzo mari proposed to MUJI to be included in the collection.

a few notions of mari’s project criteria were addressed in the exhibition, such as standard / the utopia of everyday things; joints / how are the parts assembled; archetype / branches and leaves growing from the roots; beauty / thoughts hidden behind the form and play / the origin of a project.

‘to change: enzo mari and the chestnut tree project’ – exhibition organized by MUJI, curated by keiji nagai, 2019

image courtesy MUJI

standard / the utopia of everyday things

‘standard’ can be understood as ‘criteria’ mari says. ‘the etymology of ‘standard’ is ‘étendard’, the french word for ‘flag’, and the origin of the word ‘standard’ does in fact have the meaning of ‘flag’ or ‘banner.’ the word ‘étendard’ appears in the lyrics of la marseillaise, a revolutionary song of the french revolution which later became the french national anthem.’

‘what he wants to change is not the ‘form’ of things, but rather the society, economy and the system of production system in order to get closer to this utopia. to do that, mari has talked to people with sincerity and sometimes even raising his voice in doing so. it was from one of these dialogues that he told us the story of the ‘chestnut tree.’ keiji nagai.

one of the flags raised for the french revolution actually symbolises ‘equality’. it is mari’s theory that the revolution, which aroused from the thirst for equality, was one of the historical events that would lead to modern design. there used to be a time when very few people could possess things, but suddenly people could experience ownership thanks to mass production. but the people who hold the ‘flags’ high must make sure that standards do not get compromised.

‘while mari probably has the awareness that the utopia of equality would never exist anywhere, he has nonetheless raised the ‘flag’ of a utopia that would come true through ‘things’. by working on projects, mari would continue to voice out this theory to people. good designs can make a change. it may be worthwhile to return to the origin of design once more and think about the potential of ‘things.’ keiji nagai.

‘to change: enzo mari and the chestnut tree project’ – exhibition organized by MUJI, curated by keiji nagai, 2019

image courtesy MUJI

I was a student of enzo mari and back in the 80s he underlined the importance of the french revolution for our design education. ‘I’m trying to work towards collective values. by destroying the idea of the king, the french revolution also destroyed the idea of GOD. the bourgeois had faith in the new, free and productive city is itself, a denial of the old religious forms of sacrality. as soon as the idea of GOD had been destroyed, the first phase of need for the liberated slaves was to take possessions of the material goods that had belonged to the king. but once this phase, which is entirely understandable, had been surpassed, at least psychologically, for many, the intent became to take the place of the king. we have to find the ways and the mechanisms to re-establish the sacrality of the other, otherwise the world will destroy itself.

it is still a discourse that has to find a voice.‘ enzo mari

joints / how are the parts assembled

changing parts also changes its entirety. relating everyone involved to every part of the project, mari has been passionate about creating joints, focusing on simplicity. his joints were developed with the intention save time for the factory and for people who would have had to struggle with the repetitive work of screwing. the progettista (designer) is in a position to understand the overall flow of manufacturing and the work of all the people involved. in this sense, he also possess the potential to change the movement of the hands of these working people as well as their working style. the joint is a symbol of how small changes can build towards an ideal where everyone actively participates in the work. it also raises the question, how do you engage in your work?

a view into the MUJI exhibition

image courtesy MUJI

archetype / branches and leaves growing from the roots

somewhere in the world today, ‘new’ chairs are being designed. however, mari mentioned that ‘there are few chairs in history which are truly innovative and new.’ he would refer to them as ‘archetypes’. one representative example is the bentwood thonet chair, invented by Michael thonet in the 19th century. the bentwood technology enabled mass production and compact transportation with ready-to-assemble kits. ‘we don’t need to design something just so to make it look different! it may be more meaningful to ‘grow’ such archetypes, their derivatives and useful variations, just as healthy branches and leaves can grow from the roots. it is perhaps time that we ought to get to know this tree.’ enzo mari

a view into the MUJI exhibition

image courtesy MUJI

beauty / thoughts hidden behind the form

‘there are many processes in the background of any design and there is much know about the thoughts behind the form. mari disliked how the success of industrial products are evaluated based on the idea of ‘beauty’. he would explode in anger when the viewer stops thinking as soon as they are captivated by ‘beauty’. his experimental projects introduced the essence of art into design by utilising the functions of machine tools. he considered the design and operation of such machinery as craft technologies and often observed factories and the machineries before he started on new projects.’ keiji nagai.

a view into the MUJI exhibition

image courtesy MUJI

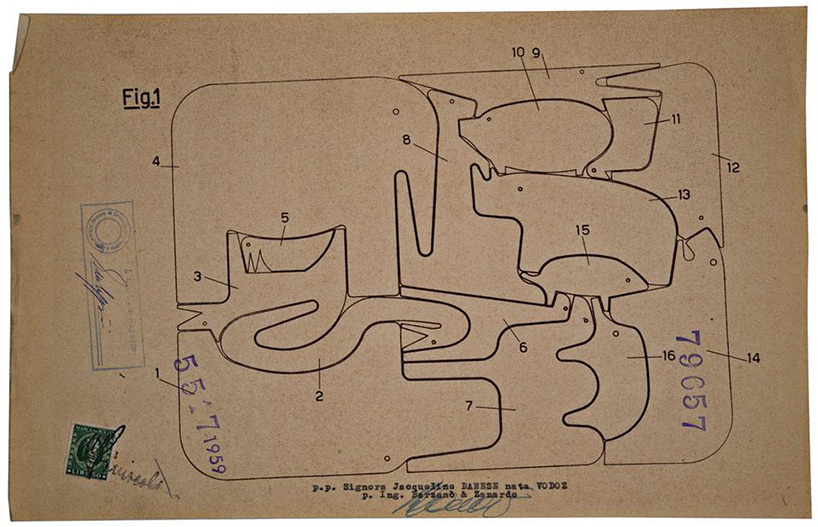

play / the origin of a project

many of mari’s early projects were toys for children. children learn every day at an astonishing speed, and feel great joy when they discover and understand something by themselves through play. however, the best-selling children’s toys have the fastest cycle of consumption. in opposition, mari tried to encourage children’s independence by introducing play without a manual. play would be different all the time and would not become so quickly obsolete. he invested time in his picture books (in collaboration with iela mari, his first wife) where every single illustration was a result of an enormous amount of studies and research. ’16 animali’ is a puzzle where 16 animals fit perfectly in a rectangular box. I was gifted a set and my children played all sorts of games with them, in their different ages. this project has been something that appeals to both children and adults. ‘enzo mari shows us that one of the most important things in life is the ability to sustain a project and maintaining it with passion.’ keiji nagai.

a view into the MUJI exhibition

image courtesy MUJI

a diagram of mari’s objects that were shown in the exhibition

image courtesy MUJI

enzo mari, drawing of ’16 animali’ for danese, 1959

image courtesy of danese

everything he has managed to achieve or even just conceive, using a complex method that would be incomprehensible and inapplicable for anyone else, has been organized, classified and diligently preserved in his endless, paroxysmal and perhaps paranoid archive.

happening now! thomas haarmann expands the curatio space at maison&objet 2026, presenting a unique showcase of collectible design.