‘very little design is actually great, very little of it is even any good, most of it is mediocre, and an enormous amount of it is damn right bad‘, says alice rawsthorn, world-renowned design critic and author of books hello world and the most recent design as an attitude. recently taking to the stage at design indaba 2019, she is making an effort to explore design in its most unflattering guises, and there’s good reason why…

alice rawsthorn expressed her thoughts on stage during the design indaba conference 2019. she uses a digital printer as a useless bad design example, the single most requested product in rage rooms globally, chosen for their countless faults and stress-inducing malfunctions.

image © design indaba

‘bad design is a problem that bedevils all of us and unless we understand it, how on earth can we get to grips with it?’ by paying attention to bad design alice rawsthorn wants to make it easier to avoid, and for designers to make mistakes far less often.

but in an industry thats quicker to laud than criticize, how do you begin to identify the failures? rawsthorn outlines 8 categories: pointless, useless, lazy, thoughtless, ominous, untrustworthy, offensive, and last but not least, good intentions but…

pointless bad design example: google glass steered its designers into thinking the average person would want a camera permanently attached to their face, unintentionally filming everyone and opening themselves up to lawsuits for privacy infringement. google stopped production of glass after 18 months and has since tried to reinvent it, but never convincingly.

image © mikepanhu

in her quest to name and shame design sinners, albeit with good intention, rawsthorn takes to task legendary examples both past and present. at the top of the list, buckminster fuller and the dymaxion car. tooted for its fuel-efficiency, the futuristic vehicle could barely make it through prototype testing. with one destroyed by fire, another in a crash, and a final prototype sold for parts, the dymaxion car ended up in history’s scrapheap, along with countless concepts, prototypes, and ideas never been brought to fruition.

that’s why bad design is so difficult to spot. beyond poorly designed architecture or legendary tech failures (the protagonists of rawsthorn’s more humorous anecdotes), serious perpetrators and their creations, whose effects are far more damaging to the planet, are often laid to rest in garbage piles around the world. in a state of limbo, their impact is no longer felt by fickle consumers but the communities they are now slowly toxifying.

lazy bad design example: the notorious agbogbloshie dump, a place where electronic and digital products are dumped, failing to decompose and poisoning the land as a result. lazy design makes the products difficult to recycle, one example being copper wire, covered in black rubber and therefore unidentifiable to optic sensors in recycling plants.

image courtesy of environmental justice atlas

after being schooled on the not-so-good, the bad, and the ugly, designboom caught up with alice to talk about some more recent controversies, the issues facing the design industry right now, and the newly-founded power of digital media in the 21st century that is taking them to task…

designboom: you referenced the recent onslaught of bad design from fashion brands like gucci and burberry. do you think that this is consequential of an industry that is too demanding on creativity or do you think it is a generational naivety?

alice rawsthorn: actually, I think it’s a different thing. I think that the differences that brands who perpetuate racist stereotypes, or homophobic stereotypes, or gender stereotypes are just likelier to be detected now and called out on it. so unfortunately, fashion brands in particular have perpetuated all of those cliches over the years but given that they tended to have a close relationship with the fashion media they were less likely to be reported on whereas now they’re named and shamed on social media. I mean the so called ‘gucci blackface sweater’ had been on sale for several months without anyone noticing. then suddenly there’s a twitter storm about it and quite rightly, I mean what possessed gucci to produce it? so I suspect it’s established traditional practice that now they’re far likelier to be detected on and hopefully that will be they’ll be much more vigilant in future.

image © gucci

DB: so digital communications and a sense of responsibility amongst consumers is working together to take bad design to task?

AR: I think those are huge factors. for example the burberry now notorious ‘noose’ which when I mentioned it at the conference people were covering their eyes. I mean burberry was called out by one of its own models who because of her personal experience was particularly sensitive to that, she posted about it on her instagram with commendable courage because she could have thought well modelling career now over, you know, having offended a powerful, highly capitalized brand like burberry, whereas as it is they had to apologize immediately and abjectly and hopefully wont perpetuate something like that again.

DB: you mentioned the danger of biometrics in the future, and there’s also a lot of discussion right now around driverless cars and programming morality. as these things evolve, they demand a consciousness when it comes design. can you talk a little about the importance of this?

AR: when we look at the application of technology, which partner with new technologies, which obviously has been a primary role of design forever, you know, long before the industrial revolution and the digital age, I think that because of artificial intelligence, whether it’s neurorobotics or whatever, these technologies will affect so many areas of our lives, that the role of design is more important than ever before. I think a fascination but also terrifying aspect of them is the moral implications of every technological application. so driverless cars are a classic example. you can say that they are less likely to cause congestion, they will save us from the problems caused by tired, inattentive, drunk, or lousy drivers, or you could be terrified at the thoughts of unknown robotics at the helm determining the course of our roads.

image © fuse project

DB: there is an element of not knowing or fully understanding these technologies, and I think that can cause concern amongst consumers…

AR: definitely. one of the most controversial instagram posts that I ever made was about the snoo, the robotic crib by fuseproject. half the respondents said ‘this is the best thing ever, if only it had existed eight years ago when my kids were babies and weren’t sleeping’, whilst someone else accused it of child abuse. it absolutely nailed questions of bringing up children and caring for babies, which of course, are of the utmost importance to us. but people interpret morally in very different ways as to what is or isn’t responsible. I think that in each of these applications, those fundamental questions need to be asked to a greater degree than ever before. so actually, it makes design much more important.

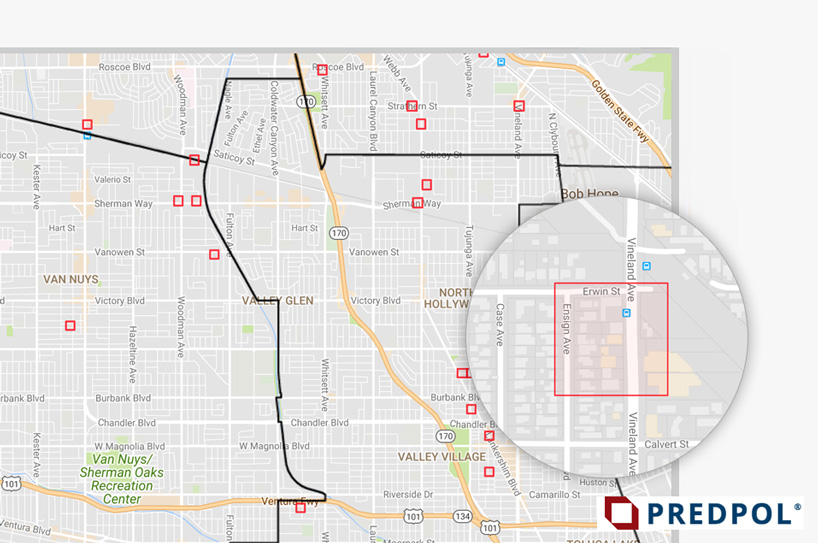

thoughtless bad design example: powered by artificial intelligence, predpol software was supposed to help police anticipate where crime would take place. the problem was that data used was historic and perpetuated stereotypes, focusing attention with wrongful justification, and therefore leaving other areas unpoliced and vulnerable to crime.

image © predpol

DB: is there a value then, to be seen in bad design? because it brings these issues to the forefront, or it works as a magnifying glass to identify issues that need resolving in some way?

AR: I think it’s the magnifying glass effect, because bad design itself doesn’t have a value. but if bad design is called out and used as a cautionary tale. so whether you know, apple did overhaul its relationships with subcontractors after the exposes of supposedly exploitative employment practices, it has made recent efforts to improve its environmental record and so on. gucci and burberry I suspect will be thinking much more carefully about which clothes they send onto the runway and what kinds of colors they put on their sweaters and feature, and that can only be good.

image © zipline

DB: we spoke about the idea of consciousness, and there’s a palpable sense of it here at design indaba. technologists are utilizing drones to send out medical supplies, and there is a significant focus on plastic waste, packaging and efforts to reduce negative impacts on the planet. this is something to be hopeful about. why are young designers inherently conscious of the negative impacts design can have nowadays?

AR: broadly speaking I think that we’re in a period where the practice and possibilities of design have been absolutely transformed by digital technology. so very familiar, relatively inexpensive, and accessible digital tools, whether it’s crowdfunding platforms, computers whose processing power is powerful enough to manage quantities of complex data, social media, all of these advances which are now utterly ubiquitous and taken completely for granted, they have had a profound impact on so many areas of our lives.

presented during design indaba 2019, mirjam de brujin has designed a system where various products can be bought in capsule form and prepared using water from the consumer’s home, therefore decreasing the amount of plastic needed to bottle products that contain mostly water.

image © mirjam de brujin

AR continued: I think the combination of that in design has been transformational. it has liberated design from designers and their roles in the industrial age. this was an age where they focused predominantly, not exclusively, but predominantly on commercial projects, generally executed under instruction from someone else into much more entrepreneurial politically, socially, an ecologically ambitious figures who can initiate, fundraise for, and execute their own projects in accordance with the causes that they believe in most fervently. for example, if you look at probably the highest profile of these sorts of attitudinal, design endeavours: the ocean clean up array. they raised over $30 million from crowd funding grants and other donations to design prototype, and test the original system and get it out live in the pacific.

DB: because there has been a few issues with it so far…

AR: there has, but they call it back to dry dock and I think it gives people a much more realistic expectation of projects like that. you don’t wave a magic wand and they all work, but raising that much money has enabled them to take those risks. if it does work in the end, then first of all it will help to tackle one of the biggest pollution problems all the time, which is an amazing thing to do, but it will also make it much easier for other ambitious, worthwhile design endeavors to raise funding. and if it fails, it’s going to be a lot harder.

image © formafantasma/ikon

DB: is one of the biggest issues facing design at the moment, the fact that there’s just too much stuff? and if that is the problem, how does that reconcile with an industry driven by production, commerciality and demanding consumers?

AR: I think it’s a question of tense there. it’s an industry that was driven by production and demanding consumers. and undoubtedly the most people still see design as a source of all the plastic trash that’s clogging up the pacific, rather than a genius way of removing it, and enabling us to live more responsibly. so designers now have an opportunity and I think a responsibility to challenge that, but that will be determined by the quality of the solutions that they develop. design is instinctively and inherently a resourceful and resilient field that’s constantly evolved over time to adapt to new challenges and changes. so there are commercial opportunities, as well as personal and moral opportunities in all these new areas. it’s really up to designers to design intelligent, appealing, effective and efficient ways of dealing with issues like digital waste, plastic pollution, and so on. and there are fantastic examples: studio formefantasma’s ‘ore streams‘, you know, really charting colossal, illicit trade and global digital waste, I think is fantastic.

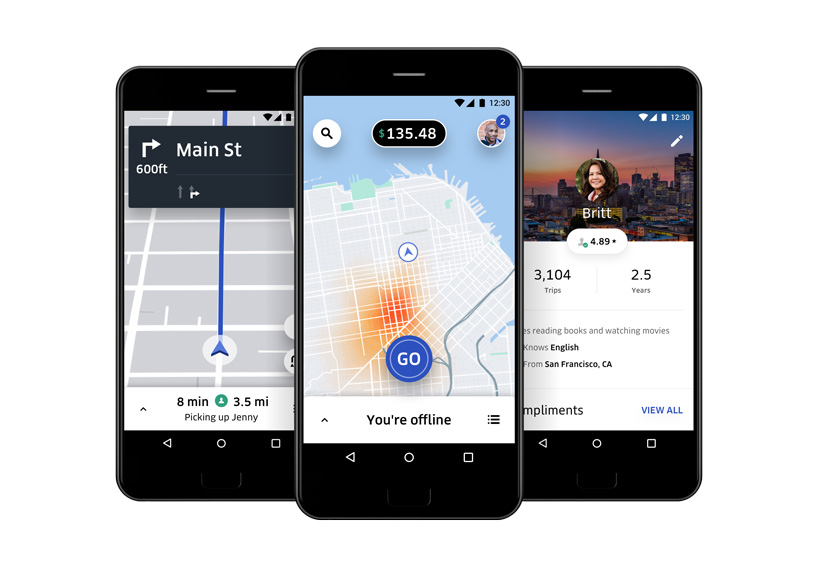

ominous bad design example: uber uses a business model providing easily accessible, very affordable private cars but has been accused of labor exploitation and poor security whilst contributing to traffic congestion and pollution.

image © uber

DB: you highlighted the fact that design touches many different aspects than just the final product. there’s the business model that needs to be designed well too…

AR: and it is designed, it’s just not generally seen like that. one example of bad design is uber as a business model. on the commercial criteria that inspired uber, the need was for a relatively affordable, easily accessible private car service, and this business model was designed to deliver in a potentially profitable way. unfortunately, because of the financial pressures imposed by that model, it has been mired in accusations of labor exploitation and periling with safety and security of its passengers, increasing congestion and pollution unnecessarily and in all the places where it operates, huge political regulatory clampdowns lawsuits, protests and so on. it’s become the villain of the gig economy and a deeply toxic and rather troubled brand with serious business problems.

DB: it’s the same with brand’s like deliveroo who have suffered similar teething problems. is it lack of long term planning? is it the fact that these are new business models so there is lack of regulations?

AR: well, I think it’s all of the above. but I think it’s also questionable as to whether some of those businesses – not all of them – care about what we would see as the negative aspects of them or whether actually labor exploitation which although is not so new unfortunately, has historically been ignored in business models or simply seen as a way of boosting profits. it’s like bad design, it’s existed forever. unfortunately, people have been unfair and exploitative towards other people. I also think, if you looked at some of the rhetoric from the initial executives of uber, there was this sense that they were just going to give it a go. these were genuinely new models, the existing legal and regulatory framework hadn’t been designed to deal with any problems, difficulties and pressures that they would eventually create and impose, so it needed redesigning. whilst the regulators and politicians raced to catch up they took advantage of a hiatus.

untrustworthy bad design example: trust in apple was shaken when it was alleged that a software update was designed specifically to drain the batteries of existing apple devices to encourage owners to buy new apple products.

image © @mnm_all

DB: so, in one word, how can we stop designing badly?

AR: think.

offensive bad design example: the frida kahlo barbie was released to celebrate international women’s day in 2018 in response to a growing interest in feminism. the problem was there was no evidence of kahlo’s disability, her dress had been europeanized, and even the monobrow had been manicured. it was banned in mexico as a result.

image © mattel

DB: is there somewhere that design has the potential to make positive change but isn’t right now?

AR: all over the world. look at the mess we’re in.

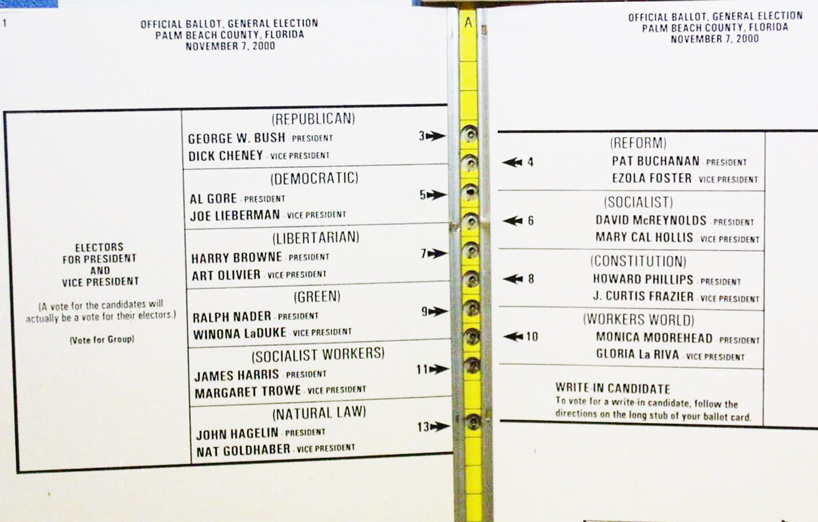

good intentions but… bad design example: in theory this butterfly ballot paper would make it easier for voters in the 2000 us presidential election to look over all information. in reality it led to thousands of complaints voicing people’s concerns that the layout had potentially confused their votes.

image © anthony

DB: and finally, as a purveyor of design what is the most important thing happening right now in design in your opinion?

AR: I think that this is an extraordinary period when design really has an exciting opportunity to play a much more powerful role in our lives. but that will have an impact on the design solutions that are developed or have a quality that proves that designers deserve to do so. design depends on the support of the power structures around it, whether it’s politicians, investors, ngos, educators, whatever, in order to be implemented. it is not going to win and critically sustain that support unless it works. I think it’s absolutely imperative that the designers who are embracing the challenge and the opportunity of working on these huge very important problems really rise to the challenge by dealing with them with intelligence and sensitivity because otherwise, if they fail, it will be much, much more difficult for design to convince people that it should be entrusted as part of the solution to such issues in future.

happening now! swiss mobility specialist schindler introduces its 2025 innovation, the schindler X8 elevator, bringing the company’s revolutionary design directly to cities like milan and basel.