‘des cheveux et des poils’ to debut at musée des arts décoratifs

Following the success of the exhibitions ‘La mécanique des dessous’ (2013), ‘Tenue correcte exigée !’ (2017) and ‘Marche et démarche’ (2019), the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris continues to explore the relationship between the body and fashion in its latest show on hair styles and body hair grooming. Titled ‘Des cheveux et des poils’ (Hair & Body Hairs), and running from April 5 to September 17, 2023, the exhibition demonstrates how hairstyles and the grooming of human hair have contributed to the social construction of appearances for centuries.

© Aurélien Farina | Jacob Ferdinand Voet — Portrait of a Man (before 1689), France | © Sotheby’s Art Digital Studio | model image © Virgile Biechy

‘Hair is an essential aspect of one’s identity and has often been used to express our adherence to a fashion, a conviction, or a protest while invoking much deeper meanings such as femininity, virility, and negligence, to name just a few. In an atmosphere where shades of blond, brown, and red evoke the main hair colors, the course, divided into five themes, questions what makes hair, in Greek-Roman and Judeo-Christian cultures, an attribute of the animal and wildness and explains why hair had to be constantly tamed to remove the woman or man from the beast,’ writes the museum.

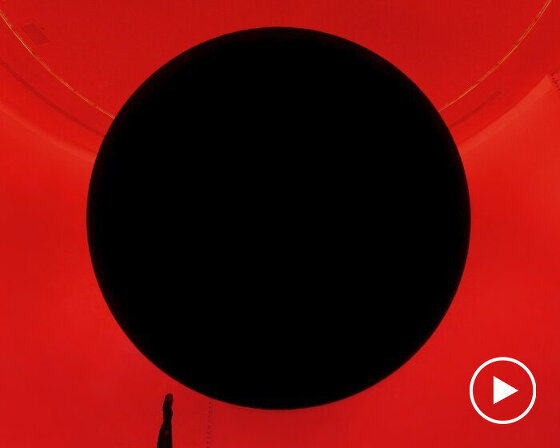

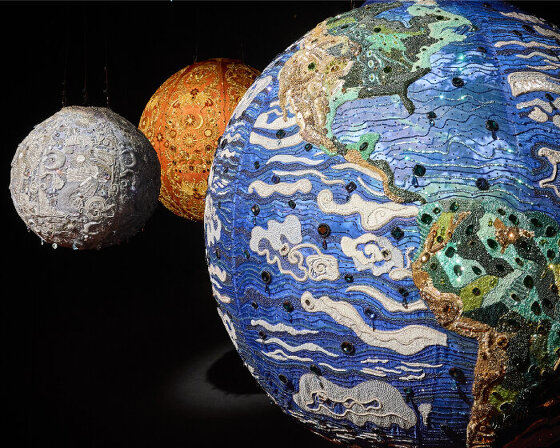

‘Des cheveux et des poils’ scenography | image © Christophe Dellière

‘Des cheveux et des poils’ will showcase 600 works, starting from the 15th century and leading up to the present day, with themes inherent to the history of hairstyle and pose questions related to facial and body hair. The trades and skills of yesterday and today are highlighted with their iconic figures: Léonard Autier (favorite hairdresser of Marie-Antoinette), Monsieur Antoine, the Carita sisters, Alexandre de Paris, and, more recently, studio hairdressers. In addition, great names in contemporary fashion such as Alexander McQueen, Martin Margiela, or Josephus Thimister are present with their spectacular creations made from this unique material that is hair. The exhibition takes place at the Christine & Stephen A. Schwarzman’s fashion galleries of the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, with the scenography created by David Lebreton of the Designers Unit agency.

Marisol Suarez, braided wig | image © Katrin Backes

FASHIONS AND EXTRAVAGANCE

The first part of the exhibition opens with the study of the evolution of women’s hairstyles, a true social indicator and marker of identity. In the Middle Ages, obeying the command of Saint Paul, the wearing of the veil was imposed on women until the 15th century. Gradually, they abandon it in favor of extravagant hairstyles constantly renewed. In the 17th century, the hairstyle à la ‘l’hurluberlu’ (dear to Madame de Sévigné) and ‘à la Fontange’ (after the name of the mistress of Louis XIV) were symbolic of true fashion phenomena. Around 1770, the high hairstyles called poufs were undoubtedly the most extraordinary Western hair fashions. Finally, in the 19th century, women’s hairstyles – whether inspired by ancient Greece or called ‘à la giraffe’, in tortillon, or ‘à la Pompadour’ – are just as convoluted.

image © Christophe Dellière

WITH OR WITHOUT HAIR?

After the hairless faces of the Middle Ages, a turning point occurred around 1520 with the appearance of the beard, a symbol of courage and strength. In the early 16th century, the three great Western monarchs, Francis I, Henry VIII, and Charles V, were young and wore beards, which were associated with a virile warrior’s spirit. However, as the 1630s approached and reached the end of the 18th century, the hairless face and the wig became the hallmarks of courtiers. Facial hair did not reappear until the early 19th century with the mustache, sideburns, and beard: this century was by far the hairiest in the history of men’s fashion. Many small objects (mustache wax, brushes, curling irons, wax, etc.) testify to this enthusiasm for mustaches and beards.

During the 20th century, the rhythm of bearded, mustached, and smooth faces continued until the return of the beard among Hipsters in the late 1990s. The maintenance of hairiness among these young urbanites has given rise to the barber profession, which has disappeared since the 1950s. Today, the thick beards tend to give way to the mustache that had deserted faces since the 1970s.

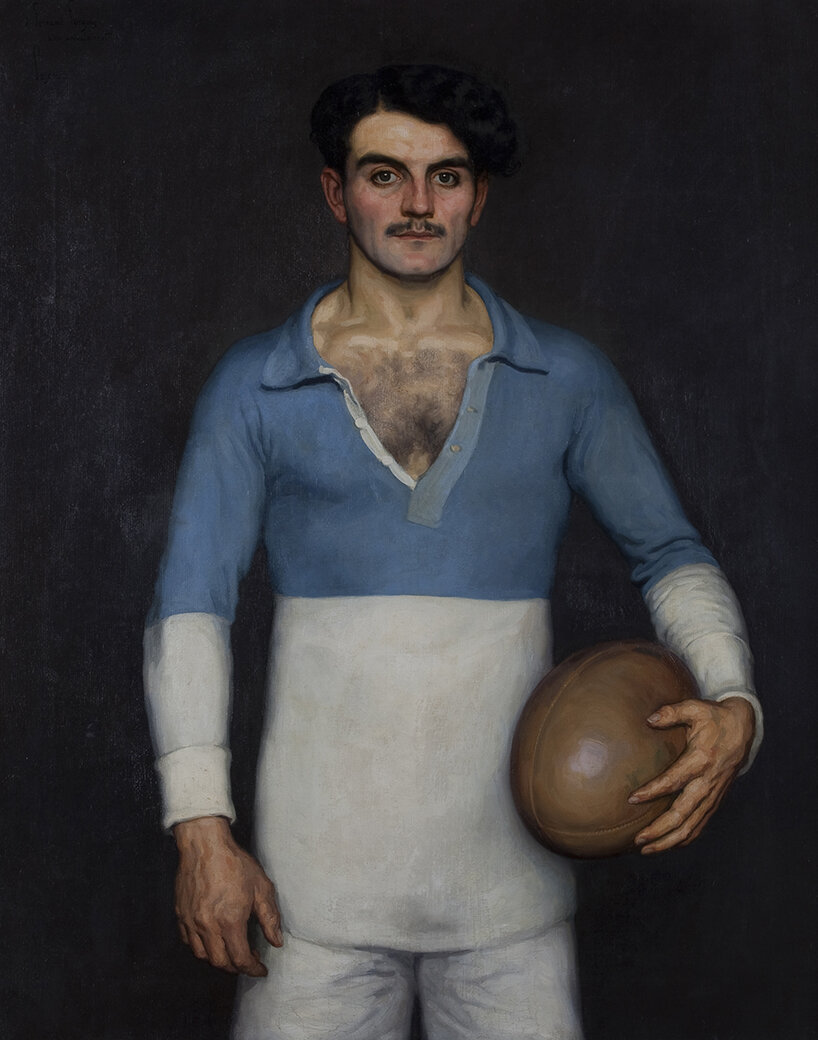

Eugéne Pascau — Fernand Forgues, captain of the Aviron Bayonnais (1912) | oil on canvas | © A.Arnold | Musée Basque et de l’Histoire de Bayonne

The choice of keeping, eliminating, hiding, or displaying hair on other body parts is also a subject of history that the exhibition addresses through the representation of nude bodies in visual arts and written testimonials. Hairiness is rare or even absent from historical paintings. The hairless body is synonymous with the antique and idealized body, while the hairy body is associated with masculinity or even triviality. Only enthusiasts of virile sports such as boxing and rugby, as well as erotic illustrations or medical engravings, show individuals covered in hair.

Around 1910-1920, when women’s bodies were exposed, advertisements in magazines touted the benefits of hair removal creams and more efficient razors to eliminate them. In 1972, actor Burt Reynolds posed naked, hairy body for Cosmopolitan magazine, but fifty years later, an abundance of hair is no longer in fashion. Since 2001, athletes being photographed naked for calendars like Les Dieux du Stade (The Gods of the Stadium) have had rigorously controlled hairiness.

image © Christophe Dellière

INTIMACY, HAIRPIECES, AND COLORS

Hair styling is an intimate act. Moreover, a well-born lady could not show herself in public with her hair down. A painting by Franz-Xaver Winterhalter, dated 1864, depicting Empress Sissi in a robe and with her hair untied, was strictly reserved for Franz Joseph’s private cabinet. Louis XIV, who became bald at a very young age, adopted the so-called ‘bright hair’ wig, which he then imposed on the court. In the 20th century, Andy Warhol had the same misfortune: the wig he wore to hide his baldness became an icon of the artist.

Nowadays, hairpieces and wigs are used in high fashion, during runway shows, or, of course, to compensate for hair loss. The natural hair colors and their symbolism are studied, along with what they convey. Blonde is said to be the color of women and childhood. Red hair is attributed to sultry women, witches, and famous stage women. As for black hair, it would betray the temperament of browns and brunettes. Artificial colors are not forgotten, from the experimental colorations of the 19th century to the more certain dyes from the 1920s. The show also spotlights the work of the hairdresser Alexis Ferrer who creates digital prints on natural human hair.

Lodewijk van der Helst — Portrait of Adriana Hinlopen (1667), Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum | © Rijksmuseum

TRADES AND KNOW-HOW

The exhibition also reveals the different hair professions: barbers, barber-surgeons, hair stylists, wigmakers, ladies’ hairdressers, etc., through archival documents and a host of small objects: signs, tools, various products, and the astonishing perming machines and dryers of the 1920s. In 1945, the creation of haute coiffure elevated the profession to the rank of an artistic discipline and a French savoir-faire. 20th-century hairdressing is marked by Guillaume, Antoine, Rosy, and Maria Carita, Alexandre de Paris styling princesses, and celebrities. Nowadays, outstanding hairstyling is mainly expressed during the fashion shows of prestigious fashion houses. Sam McKnight, Nicolas Jurnjack, and Charlie Le Mindu were invited to the exhibition to create extraordinary hairstyles for top models and show business personalities.

image © Christophe Dellière

A LOOK BACK AT A CENTURY through ‘des cheveux et des poils’

Finally, a special focus evoked the iconic hairstyles of the 20th and 21st centuries: the 1900 chignon, the 1920s garçonne haircut, the 1930s permed and notched hair, the 1960s pixie and sauerkraut, the 1970s long hair, the 1980s voluminous hairstyles, the 1990s gradations and blond streaks, not to mention afro-textured hair.

The arrangement of hair in a particular form can reveal the belonging to a group and manifest a political and cultural expression in opposition to society and the established order. More ideological than aesthetic, the punks’ Iroquois crest, the grunge’s neglected hair or the skinheads’ shaved heads reflect iconic moments of hair creativities. Wearing the hair of another, known or unknown, has an eerie dimension, and this superstition seems well-entrenched.

Despite these apprehensions, some creators transcend this familiar material into fashion objects. This is the case with contemporary designers such as Martin Margiela, Josephus Thimister, and Jeanne Vicerial. The question of identity, treated lightly or more deeply, is often at the heart of the reasoning, whether the hair is real or fake.

Alexis Ferrer — Wella Professionals Global Creative Artist | ‘Printed Hairpiece’ (2021) | collection ‘La Favorite’ | model: Emma Furhmann, Agence Blow models | image © Rafa Andreu

Charlie Le Mindu —’Blonde lips’ | Spring-Summer Collection 2010 called ‘Girls of paradise’, Fashion Week at the Royal Festival Hall, 19 September 2009, London | image © Samir Hussein /Getty Images

image © Christophe Dellière