‘MIGRATIONS’ AT THE VENICE ART BIENNALE 2022

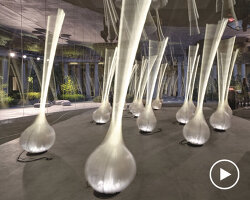

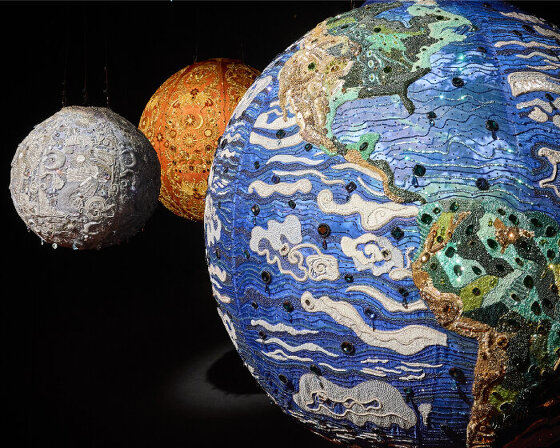

Part of ‘The Milk of Dreams’, the International Art Exhibition of the Venice Art Biennale 2022, Marguerite Humeau’s ‘Migrations’ is a new body of work made from biological and synthetic resin and polymers, salt, algae, seaweed, bone, pigments, mineral dust, ocean plastic, glass, and stainless steel. The installation is composed of three sculptures named after ocean currents: El Niño, La Niña, and Kuroshio. Somewhere between levitating, collapsing, and almost flying away, the three sea creatures of the artist’s mythological ecosystem express an understanding of mortality that transcends the domain of humans. ‘I thought that maybe because of climate change and mass extinctions, animals are also getting conscious of their own death, and maybe they’re developing their own rituals, mythologies, and spirituality,’ Humeau tells designboom. ‘In the past three years I’ve developed a series of death rituals and dances, many of them about marine mammals specifically because I do lots of research around their existing rituals,’ the French, London-based artist adds. Find out more about ‘Migrations’ and the work of Marguerite Humeau on our interview below.

all installation views from the 59th International Art Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia: Marguerite Humeau, Migrations (El Niño, Kuroshio, La Niña), 2022 | images by Roberto Marossi, courtesy the artist, C L E A R I N G and White Cube

video: Marguerite Humeau, ‘Migrations’, 2022. video: Jon Lowe Courtesy of White Cube

INTERVIEW WITH Marguerite Humeau

designboom (DB): Can you tell us a few things about the new body of work you are presenting at the Venice Biennale?

Marguerite Humeau (MH): The work is called ‘Migrations’, and it’s composed of three sculptures called ‘El Niño’, ‘La Niña’ and ‘Kuroshio’. They are named after sea currents. It’s actually an extension of a work I did in 2019, which started for my show ‘MIST’ at C L E A R I N G, Brussels, and then ‘High Tide’ for the Prix Marcel Duchamp prize. My original speculation was about the origin of humankind, and how a lot of researchers think that we became spiritual when we became conscious of our own death, from an individual point of view, but also as a species. There are a few researchers that think this, and especially one who I really love is Joseph Campbell. He talks about how, for him, this moment in time was the beginning of spirituality and the birth of mythologies. Because the first impulse we humans have had when we realised our own death, as individuals, but also the death or extinction of our species, has been to try to find ways to transcend it.

Kuroshio and La Niña

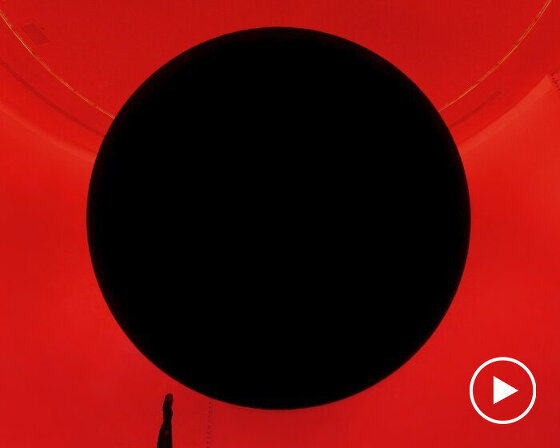

MH (continued): When you look at many religions around the world, or grand narratives, or mythologies, they’re all connected one way or another to the idea of eternal life or questions like, ‘where do we go after we die?’ or, ‘do we get reborn?’. So I thought that maybe because of climate change and mass extinctions, animals are also getting conscious of their own death, and maybe they’re developing their own rituals, mythologies, and spirituality. In the past three years I’ve developed a series of death rituals and dances, many of them about marine mammals specifically because I do lots of research around their existing rituals. Actually one of the inspirations behind the show in Venice comes from a video I saw of a female whale that was carrying a baby that had just died. For many weeks she was carrying it on her head. For this work specifically, I was also thinking about climate change, the rise of the water, and especially in Venice because the water is so overwhelmingly present everywhere; it seems that the city is counting the millimetres until it literally drowns. What do we do when this happens? I guess we’re forced to migrate. So I was interested in the idea of migration, as in to be physically forced out of where you live to go somewhere else. But also the migration of the mind, the migration of the soul once you die. I was thinking about a group of marine mammals who are migrating. The show operates on different levels. Maybe this is my most mysterious work, because there are different ways of interpreting it.

El Niño, La Niña, Kuroshio

MH (continued): I don’t know if you experienced the same during COVID, but I felt that there was a huge change of paradigm. In previous works I had been more interested in accelerating life to the point it becomes eternal, through technologies or other means. I was interested in accelerating this process to the point when it becomes horrifying. This has totally shifted now, and I’m much more interested in vulnerability, imperfections, and fragility. There is something quite overwhelming about what’s happening in the world at the moment. Then, the figure of Atlas came to mind, the Greek titan who’s carrying the sphere of the heavens on his back. To be honest, I’ve felt very much like that in the past two years, like you’re almost overwhelmed by your own weight. Thinking about the challenges that we humans have to tackle, especially with climate change. It is very complex to understand how we can act on an individual level, what we should do to have a real impact in the world, and also how to manage those challenges at a collective level.

La Niña

MH (continued): So, I had this image, and then I had the image of the whale carrying the baby, and like that I started to think about bubbles, or big water drops that could be like the bags one might carry on their shoulder when they’re migrating, or they could also be crystal balls, or spheres in which you can project your future but also your memories, your past. And when you migrate, what do you take with you? What is it that you want to protect? I was playing around with that and developed the work like this.

I wanted to have one of the beings in this ecosystem, in this group, totally overwhelmed, like Atlas, who’s totally overwhelmed by its own weight. I wanted it to seem really fragile, almost a bit sick, one of its ‘arms’ looks almost like it’s broken. I worked really hard on the balance, and I was also thinking that yes, we’re on the cusp of falling, but maybe we could also transcend. So the beings look like they’re levitating, almost falling, collapsing, but also almost flying. They’re all slightly unbalanced, but also kind of moving forward. This was quite new for me, I broke the symmetry of my work that was quite present before. I brought more imperfections, I worked on the balance, and I wanted them to feel really light but very heavy at the same time. The second being is more like it’s travelling, carrying something, maybe on their head or on their hands. And the last one is much more hopeful. It’s almost like a wave coming out and showing the way. We don’t really know where it’s heading to, but it’s heading somewhere. There’s something more hopeful about it.

La Niña, detail shot

DB: Why did you name the three sculptures after sea currents?

MH: I named them after sea currents because once I designed them, I was showing the forms to different friends to test them, and it’s funny because some of them were like, ‘that’s not even an animal, that’s a plant,’ or ‘that’s a flower’. I got many different responses. I thought that it was so interesting, because it was almost like it was the entire living world that carries Earth in a way. In the end it doesn’t matter, they could be plants, they could be flowers, they could be animals, they could be all living things that are on a mission to protect something that they’ve lost, or that they’re about to lose. So I thought about sea currents because they are such strong forces. Also, they encapsulate huge ecosystems. For example, El Niño is quite emblematic of that, as it warms up or shifts, this affects many living things. And as the currents keep changing, they will affect all sorts of living organisms and the ecosystems will be transformed.

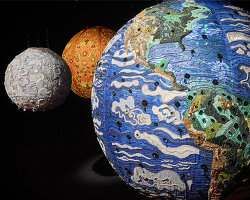

Marguerite Humeau, High Tide (The Dancer II, The Dancers III & IV), exhibition view, Centre Pompidou, Paris, 2019 | Image by Julia Andréone, courtesy the artist, C L E A R I N G New York/Brussels

DB: Can you tell me more about the materiality of the sculptures?

MH: I started to include organic and mineral materials. I am working with seaweed pigments and mineral dust and bones, that are all encapsulated within the works. I’m also interested in those materials, of course, conceptually speaking. Also, although there is a slight distance in the way the work is presented in the Arsenale, if you look really close, I wanted their skin to almost feel like it has pores and freckles, and like it’s really soft as well. I wanted to create a high level of empathy, although we don’t really know what these are exactly.

Marguerite Humeau, Waste I – 4, A respiratory tract mutating into industrial waste, exhibition view, Clearing Brussels, 2019 | frigate bird respiratory tract in resin, polyurethane, paint, silicone tubes, CO | 93 x 57 x 33 cm | image by Julia Andréone, courtesy the artist, C L E A R I N G New York/Brussels

MH (continued): I want my materials to be really ambiguous, so you never really know what they are. It’s a big question people ask me, and I can tell you the ingredients but it’s also about how you apply them and what you do with them. Recently, I’ve been much more involved personally. For example, for the big blue-ish spheres in the sculptures, I was at my fabricator’s workshop in London for the spray painting and sanding, and I also applied different textures on the surfaces. I treated them like watercolors. The sculpture on the left, if you look close enough, looks like there is a storm inside.

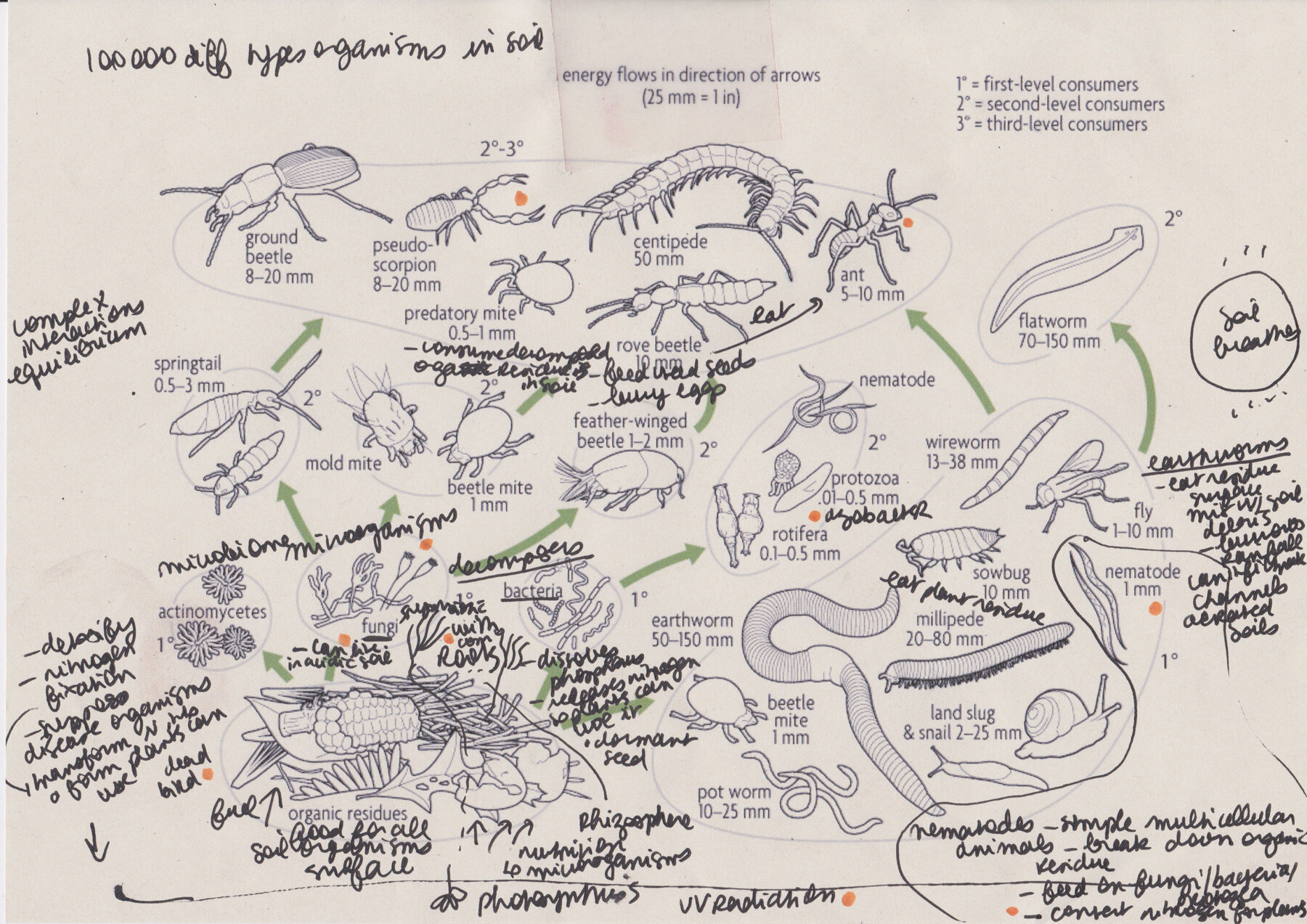

Marguerite Humeau, ‘Energy Flows’, exhibition view, Clearing New York, 2022 | image by JSP Art Photography, courtesy of the artist and C L E A R I N G New York / Brussels

DB: One thing that struck me is the scale. Its monumentality allows you to immerse yourself in it. How do you decide on the scale of your works in general? Do you also produce pieces on a smaller scale?

MH: Actually my last show, ‘Energy Flows’ at C L E A R I N G New York, was all composed of really small works around plants. I’ve been working at different scales. I’m working on a teapot at the moment, I’m doing small sculptures, drawings and bigger paintings, and in the last year I’ve done gardens and microarchitectures. But you’re right, these are some of my largest works to date. In sculpture, I always think that scale is so important and means different things. For example, with my show of really small sculptures, I was thinking of them as elixirs, so I really wanted them to feel quite intimate. I was also thinking of them almost as prototypes for new worlds, like architecture models for something much bigger.

Marguerite Humeau, ‘Ambedo’ (with Jean-Marie Appriou), 2021 | skeleton, lacquer | 58.2 x 59.6 x 36.3 cm | image by julia andréone, courtesy the artist, C L E A R I N G New York/Brussels

MH (continued): Usually, in the tradition of sculpture, one to one scale is human, and for example, one and a half might be a god-like figure. For the works at the Biennale, I didn’t start by saying I want them to be monumental. I first designed them, and then I was thinking that I wanted the part that relates to some kind of head to be at the height of a human head, so it feels like we’re entering in dialogue with them. I wanted to feel like you can almost discuss with them, but at the same time that they also feel that they are embodying something greater than us.

diagram – working document for ‘Energy Flows / Surface Horizon’, courtesy of the artist

DB: Can you tell me more about your process?

MH: I start with lots of sketches, I’m talking hundreds of pages. I usually also gather lots of reference images, and then I send them to a 3D designer who I work with. Recently I’ve changed the way I’ve been working. Before, I would send him my sketches and he would translate that into a 3D model. Now, I’m sending him sketches, but most importantly, reference images and ask him to replicate some parts. For example, I’ll ask him to replicate this organ of a whale, or this bone, or this part of a seaweed. He makes a kind of toolkit, and then he sends it back to me, and I connect them together. I play around with them, I scale them up or down, and then I send it back to him and he connects everything back together. It’s a bit of a process. About the scale, I’m usually in my studio measuring myself and things around me to understand how it would feel to be next to them. This time, we made a full model of my space in the Arsenale, including the columns that surround it, so we could try with small characters to see how it would feel like. Of course, once the work has been produced, I’m always surprised. But that’s nice as well, because I don’t exactly know how things will be in real life so it makes the process really exciting.

Marguerite Humeau, Common Moonwort, 2022 | Pigment and charcoal on paper, frame: sugars, mineral dust, plant-based and synthetic resin, wood |courtesy the artist, C L E A R I N G New York/Brussels

DB: What you’re working on at the moment?

MH: I had my show ‘Energy Flows’ at C L E A R I N G in New York that just ended. I was presenting a sort of garden-cemetery-alchemical place where I was growing sculpture elixirs to find emotions that we’ve never named, or that we’ve lost. At the same time, I was showing a series of pastel drawings that I saw as portals into the soil. I’ve been working with high precision scanning technologies to get images from the soil and understand what are all the micro interactions that happen there and what we can learn from them. And this is an ongoing series, so I’m going to show also some new drawings at Art Basel in Hong Kong. At the same time, I’m showing at the Sydney Biennial. It’s a piece that’s connected to the work I’m showing here in Venice, which I produced in 2019. It’s called ‘The Dead’ and it’s a marine mammal that seems to be floating at the surface of the ocean with its arms open, almost like a cadaver, but

reaching for some form of transcendence at the same time.

Marguerite Humeau, The Dancer V, A marine mammal invoking higher spirits, 2020 | Polystyrene, polyurethane resin, fibreglass, steel skeleton, pollution particles | 220 x 206 x 169 cm | image by Filip Claessens, courtesy the artist and CLEARING New York/Brussels

MH (continued): And my big project is the one I’m doing in Colorado, in the San Luis Valley, with an organisation called Black Cube. We managed to rent one of those huge circles that are used for intensive agriculture in the United States. The site is one kilometer in diameter, and has been unused for a while. We are developing the project at the moment. When we finish, it’s going to be the largest earth work ever made by a woman artist, so that’s a challenge. It’s a massive project and I’m really excited about it because my work is moving even more towards thinking about sculptures as portals, and as agents that can create relationships between different things. I’m not really interested in making objects in themselves, I’m much more interested in creating beings or agents in a group or an ecosystem who connect between each other, like in Venice. I have also been working on an elixir that is served with a specific teapot, again, using sculpture as a means to connect humans together or to activate something within us, or connect us to other times or spaces. All my projects are all mythological ecosystems, that are carefully researched and emerge into our reality, through sculpture or sound, via a clairvoyant like in my show Surface Horizon that took place at Lafayette Anticipations last year, or through gardens, landscapes, via an elixir or a drawing-portal, via voices or all forms of ethereal presences or manifestations.

Marguerite Humeau, Rise, 2021| Aluminium, oil, pigments

5250 x 4573 x 3234 mm | commissioned by Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo | image by Domenico Conte

MH (continued): In Colorado, it’s about the relationship between humans and the birds because there are very specific birds that migrate over the sites that are called sandhill cranes. So the connection is between the birds, the water, the rain, and satellites that are specialized in weather forecasts. The intention is to transform the land into a rain making device using physical tools, but also mythologies. I’m really excited about it, because conceptually speaking, it is a great new direction for me: how to work site-specifically, how to create new mythologies that can be active in specific landscapes, drawing from past myths and speculations about the future. I am interested in exploring the idea of humans reintegrating wider ecosystems, synchronising with and transcending through larger life flows. In Colorado, I am imagining that we transform the land into a rain-making device, a collaborative opera at the scale of a landscape, a collaboration between the land, the weeds, sandhill crames, the wind, past and future mythologies, farmers, community members, soil scientists, bird specialists and more. I also started to work with White Cube gallery and I will have my first solo show there in April 2023, and then at C L E A R I N G in Brussels.

Marguerite Humeau, Levitation, 2021 | image by Julia Andréone, courtesy the Artist, C L E A R I N G New York/Brussels

Migrations (Kuroshio, El Niño, La Niña), installation view

project info:

name: Migrations

artist: Marguerite Humeau | C L E A R I N G New York/Brussels | White Cube

location: Arsenale – the 59th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia