can art save us from extinction? — this is the pertinent question posed by the oak project, a new partnership between yorkshire sculpture park (YSP) and the university of derby. aimed at exploring our relationship with the natural world, and building upon its connection through arts, culture and creativity, the initiative will pioneer arts-participation to create kinship with nature over the next five years. the oak project has been developed in response to the university of derby’s recent psychological research, which shows that art can play an important role in motivating people to take action in protecting the environment.

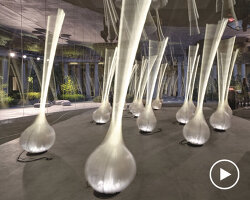

this spring, the oak project launches its first artist commission hosted at yorkshire sculpture park by artists heather and ivan morison from studio morison. silence – alone in a world of wounds — to be unveiled on world environment day, june 5, 2021 — comprises a sculptural space made of materials sourced from the west bretton estate at YSP, and sustainably sourced timber from the artists’ own woodland. the structure acts as an extended open pavilion that becomes the framework to a quiet space set within nature. informed by evidence drawn from the university of derby’s research, studio morison has delineated the work as a circle and asks that visitors refrain from conversation, creating an area of calm contemplation to stop, connect, and experience the natural surroundings. the work will become part of the landscape over time, as natural weather contributes to its decomposition and leaves only a slight indent and trace of a ring in the ground.

all images: heather and ivan morison, silence – alone in a world of wounds, 2021

courtesy yorkshire sculpture park and the oak project | photos by jonty wilde

to learn more about the oak project, designboom spoke with clare lilley, director of programme at yorkshire sculpture park, and heather and ivan morison of studio morison — read our interview in full below.

designboom (DB): why was now the moment for yorkshire sculpture park to introduce the oak project? what makes it so timely?

clare lilley, director of programme at yorkshire sculpture park (CL): we know we are at a tipping point in terms of climate change. we also have deeper understanding of the emotional and psychological impacts of contemporary life and especially of the pandemic. for several decades, yorkshire sculpture park has empowered artists to respond to and draw out layers of history and ecology of its 500-acre estate; both andy goldsworthy and david nash carried out important early research here and artists from james turrell to rebecca chesney and brandon ballengée have amplified the natural resources of this place, deepening people’s experience of it. we know instinctively and through empirical research that regular contact with and understanding of the natural world improves our mental health. altogether this makes our work with the oak project especially important and precisely well-timed. I’m certain silence will engender a sense of fascination and enjoyment, and that it will give great hope and sustenance.

DB: what research went into identifying the importance of the arts in motivating people to take environmental action?

CL: the oak project collaboration with the university of derby is a firm foundation for our ongoing commissioning programme. the university’s nature connectedness research group, led by miles richardson, has identified five pathways to nature connectedness – contact, emotion, beauty, meaning and compassion. through the senses, these pathways enliven the emotions that nature brings and the ways in which beauty reveals meaning, encouraging both caring and taking action for the natural world. silence will be part of this action-research, encouraging people to note their response to the work and to carry it into their own lives.

DB: how has working with studio morison on this first commission activated the initiative, and informed its future plans and goals ahead?

CL: any new commission embraces the unknown and it’s incredibly exciting to put your faith in artists. for many years, ivan and heather have been nurturing an ancient wood in west wales which has been central to their developing practice; they have brought decades of careful and authentic communion with the natural world to yorkshire sculpture park. late yesterday, in the pouring rain, I stood in silence with ivan morison and it was simply breathtaking – it activated a depth of breath and psychological stillness that is exceptional. we know that YSP in itself is incredibly healing for people, that it’s a sanctuary, but silence accords a new level of connection and sets a very high standard for future collaboration. it offers great optimism for revealing previously unexplored areas of our land and for projects that catalyse the best of human endeavour.

interview continues with heather and ivan morison from studio morison…

DB: how have you responded to the question, ‘can art save us from extinction?’ — what was your personal interpretation of this concern?

heather and ivan morison from studio morison (SM): the great conservationist, aldo leopold, said: ‘one of the penalties of an ecological education is that one lives alone in a world of wounds. much of the damage inflicted on land is quite invisible to laymen. an ecologist must either harden his shell and make believe that the consequences of science are none of his business, or he must be the doctor who sees the marks of death in a community that believes itself well and does not want to be told otherwise.’

recently we have been reading braiding sweetgrass by robin wall kimmerer, making – anthropology, archaeology, art and architecture by tim ingold, and diary of a young naturalist by dara mcanulty. each one speaks explicitly to what we want to offer up for the oak project.

both the botanist robin wall kimmerer and the naturalist dara mcanulty express a deep sense of loss when they look at the world around them through their professional eyes. they see what many of us may not. both talk of what is it is like to ‘live alone in a world of wounds’. their writings share their own insights into the reality of the world around us, bringing us into their grief.

‘we tend to shy away from that grief,’ kimmerer explained in an interview earlier this year. ‘but I think that that’s the role of art: to help us into grief, and through grief, for each other, for our values, for the living world. I think about grief as a measure of our love, that grief compels us to do something, to love more.’

SM (continued): our work for the oak project must open the viewers eyes to the natural world, wounds and all, and through the shared grief create action — turning towards the world for what it has to teach us.

dara mcanulty lays in the grass and exquisitely describes the sound of the grasshopper’s tympanal membrane vibrating to us.

so, our response to this commission is like fieldwork — a protracted masterclass in seeing things, hearing and feeling them. a kind of education of attention, to join with people to speculate on what life might or could be like.

it is kimmerer who can offer us some guidance towards an answer to the oak projects question to us ‘can art save us from extinction?’. we share kimmerer’s understanding of the work of art in terms of the ‘long game’, the function of which is to create the necessary ‘cultural underpinnings’ for change.

this work is a gift of time and attention.

DB: can you briefly walk us through silence – alone in a world of wounds? what should visitors expect to encounter?

SM: silence – alone in a world of wounds is a sculptural space. an extended open pavilion. a ring set within nature.

it is a space that is a kind of education of attention, that offers a protracted masterclass in seeing things, hearing and feeling them.

it is a space for silence. a pavilion where speech is not allowed. we become dara lying in the grass listening for the sounds of nature.

it is a space that is a frame for the landscape around it. it reframes the familiar making the viewer see anew. as an object it provides a counterpoint within the landscape. from within it reframes views looking out as well as creating physical perimeters around an area of the natural world.

it is a space that captures light, draws in natural sounds, holds moments of weather, allows a space of nature to speak to us.

it is a space of temporality and of lightness.

SM (continued): our materials are natural, from site, from the ground, or made from trees, reeds and grasses. walls allow air and light through – paper screens and delicate slats create patterns of light and shadow.

the structure creates a framed area of ground and nature.

the structure is generous in scale, allowing space to wander through it – slow walks along cloisters.

the structure has its own ruin designed into it. some materials will go first – paper screens will tear in the wind and rain of its first winter. thatch may begin to go the next year as animals begin to make homes in it. as water comes down the walls those made from compressed earth will begin to slump and lose their sharper minimalist edges. at this stage plants will now begin to push up through compacted mud floors. the light timber framing that held the screens will hold steady, but the thin wooden louvres begin to fall away, opening up different views, creating new patterns of light as the timber rots on the floor. visiting after some years we will find some upright elements still offering up framed moments of landscape and a ghostly outline of a space that once was. in years to come only the slight indent and trace of a circle in the ground remains.

DB: in general, how do you think art experiences can support a person’s well-being, and encourage a connection with nature?

SM: we make a grave error if we try to separate individual well-being from the health of the planet. kimmerer talks about restoring a ‘grammar of animacy’. that is no longer seeing nature is ‘it’ but as kin – like an elder ‘relative’ and to recognise a kinship with plants, hills and lakes. this is what we want for our audiences through this commission.

tim ingold helps us find a way of doing this, from his position as a social anthropologist he advocates a way of thinking through making in which sentient practitioners and active materials continually answer to, or ‘correspond’, with one another in the generation of form. we look to natural materials, we look at the landscapes they sit within, we create works that frame and heighten our experience of these places, offering us deeper understandings of them, connecting us to them.