the murals of irish artist joe caslin seem to spring up overnight. both visually commanding and powerfully subtle, his towering works of art appear like massive sketch books across the architecture of ireland’s cities. devoid of text and realized in stark monochrome, the figures of caslin’s murals both compliment and change the world around them, compelling passersby to stop and stare, if even just for a moment.

potent in their simplicity, the lofty drawings are more than just visually arresting street art. each project engages directly with the social issues of modern ireland, responding and commentating on events taking place in the surrounding community and beyond.

caslin’s most recent work ‘the volunteers’ overlooks the front square of trinity college dublin

all images courtesy of the artist

joe caslin came to international attention in 2015 with his large scale mural ‘the claddagh embrace’. taking up a prime position overlooking dublin’s south great george’s street, the image was created in reaction to the country’s then-upcoming referendum on same-sex marriage. in many ways, the piece felt like a turning point in the campaign. a country that had so long been defined by its staunchly catholic tradition now had a giant-size image of two men embracing on one of its busiest streets.

potent in their simplicity, the lofty drawings are more than just visually arresting street art

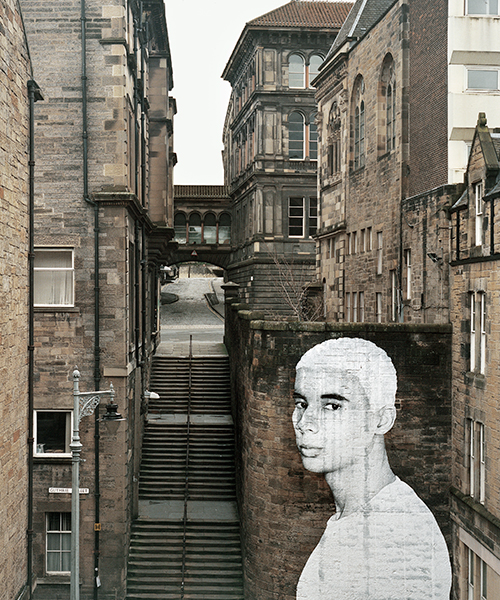

caslin’s earlier project ‘our nation’s sons’ spanned across the island of ireland and abroad to scotland, decorating cities with huge portraits of their young male inhabitants. the project aimed to highlight the demonisation of male youths based on their appearance and apparel, the collective condemnation of young men through stereotyping, and the effect of this on their mental health. caslin, who works as an art and design teacher, had seen first hand the effects of such marginalisation.

caslin came to international attention in 2015 with his large scale mural ‘the claddagh embrace’, pictured above

image by david sexton

caslin’s art is silent, powerful and unafraid of addressing the faults in a community. the figures that populate the murals — ordinary individuals — become spokespeople of their own experience, reminding viewers of the challenges they, as a population, must face together. caslin’s most recent piece ‘the volunteers’ stretches out across the façade of trinity college dublin, changing the face of one of the capital’s most visited landmarks. recently, designboom spoke with the artist about the piece, as well as his motivations, process, and the role of the artist in modern ireland.

‘our nation’s sons’ spanned across the island of ireland and abroad to edinburgh, scotland

designboom: what originally made you want to become an artist, and what first attracted you to creating murals?

joe caslin: I believe the artist has a valued place in society and that we are ‘cultivators of empathy’. our role is to be observant at all times and to do our best to create debate and feed back. to hold a mirror up; to advocate and to provoke. street art by its very nature allows the conversation between the artist and the public to be instantly engaging. it is this closeness and intimacy in dialogue that attracted me to creating large-scale public work.

the figures that populate the murals — ordinary individuals — become the spokespeople of their own experience

DB: can you talk us through the stages involved in realising one of your compositions, from the drawing board to the final product?

JC: there are many stages involved in the production an installation. it begins with a lengthy period of research. I immerse myself in the social issue I wish to examine. this could take anything between three months to two years depending on the subject matter. once candidates have been selected for the drawing they are photographed in various positions. these are then used to compose the piece. the drawing itself can take anything from two to seven weeks to complete depending on the number visual metaphors and individuals involved.

the drawing is then scanned and printed on a large format architectural printer. these sheets are then applied to the surface of the building using a biodegradable adhesive. the installation is then photographed, filmed and disseminated online.

the drawings are applied to the building using a biodegradable adhesive

image by sean jackson

DB: creating work in the public realm involves surrendering a bit of control when it comes to how that work is interpreted, especially with pieces like yours where the message is not always self evident. how does this influence the way you create?

JC: I would agree that you surrender control of interpretation your audience. this is the case indeed with many fine art mediums. additionally, my work has many mechanical and scaling similarities with advertising campaigns. however, I purposely do not include any text. as a result, I lean quite heavily on conveying the story through body language and the inclusion of artefacts relevant to the subject matter I am portraying.

I believe my audience have a strong visual library which they can use to determine the multi layered meaning of each installation. sometimes relinquishing control leads to a stronger and more varied sense of understanding.

‘the castle’, also created in response to the marriage referendum, was realized on the side of a crumbling tower

image by david sexton

DB: have you ever considered creating work for a gallery or museum, and how do you think this might impact your process?

JC: my participation in the gallery or museum environment has been very sparse. this is through no fault or failing of the gallery or museum cohort as there is a distinct shift in these organisations to bring the outside in. I feel, I have not yet reached that stage of proficiency as an artist. having an exhibition is not something I wish to do half-heartedly.

DB: ireland has seen a lot of change in the past decade — the economic crash, the marriage referendum, the ongoing campaign for abortion rights, the decline of the catholic church and more — how do you think the role of the artist in ireland has changed over the past few years, if at all?

JC: the role of the artist within society has been historically consistent, they provide a visual documentation of our social history. the stone age people used the artist to express the earth’s connection to the immense and cyclical power of the sun, the catholic church used the artist to bring their dogmas to an almost illiterate congregation, the celtic tiger allowed the artists to engage with the betrayal of business world.

the crash then showcased the artist as resilient. the marriage equality and ongoing campaign for abortion rights has showcased a desire within the general public for their emotional state to expressed and made visible. the artist has the power and capability to do this and will continue to document and enhance humanity’s future.

‘the role of the artist within society has been consistent, they provide a visual documentation of our social history’

DB: your mural for the marriage referendum occupied a huge space on dublin’s south george’s street, and your most recent work changes the face of trinity’s front square. how important is the location or building itself in the conception of each piece?

JC: securing a location can sometimes come before the drawing has been realised. my work is biodegradable and temporary and as such I get to install drawings on sites of significant national heritage. it is important that such important social issues are not pushed to the periphery or indeed onto sites of poor architectural value. having fought hard to bring an issue to the fore it would do little to install the drawing down some back alley.

caslin also created a five storey high mural in belfast in response to the marriage equality campaign

DB: can you tell us a bit about your most recent project, ‘the volunteers’?

JC: ‘the volunteers’ is a powerful new collaborative multimedia piece of public art and film, the first of a three-part series highlighting the importance of volunteerism in tackling some of ireland’s most pressing issues: drug addiction, mental health, and direct provision. the project reflects upon ireland’s century of progress and asks us what battles we must fight in the present to remake the country for the better.

I have chosen to focus this piece and its accompanying short film on the theme of decriminalising addiction. the controlled drugs and harm reduction bill is currently before the houses of the oireachtas (the legislature of ireland). both the bill and this piece attempt to humanise the complex narratives around addiction, placing treatment as a health issue and not an offense to be punished within the criminal justice system. this piece of cultural commentary features rachael keogh, an advocate in recovery from heroin addiction, senator lynn ruane, author of the legislation, and fiona o’reilly, managing director of safetynet, a primary care service to people who are homeless.

the male figure represents the doctor, a role which is frequently secondary in drug abuse intervention due to failed government policy and the mischaracterisation of addiction. ‘the volunteers’ is about the preciousness of life, and the ways we betray it, as well as the ways that we honour it with our time, passion, and attention. drawing from the example of the 1916 volunteers, who made their lives offerings for a new world, this piece looks at those who offer themselves to transform their country in a different way, today.

a mural created to raise awareness for suicide and self harm crisis center pieta house

DB: what are the most challenging aspects of realising your work?

JC: securing funding is a constant issue. provocative work is hard to finance so my work as a secondary school teacher pays for the majority of the projects. the stereotype of the street artist as a renegade figure of the night can be a double edged sword. bureaucracy can be infuriating. having to pander to state agencies can gnaw at your soul. it often turns vibrant work grey.

DB: how has your work as a teacher influenced the way you make art?

JC: all of the social issues I have made work around have come from first hand experiences within my classroom. my classroom has a community of over three hundred individuals. they each work together to find meaning from society so that they can effect change both as youth or in the future as adults. my students are usually the guinea pigs as an idea comes together. my classroom is my testing ground and my classes are contained focus groups who give immediate and honest feedback on an idea or a drawing. this honesty can at times be blunt.

‘the stereotype of the street artist as a renegade figure of the night can be a double edged sword’

DB: do you have a particular piece that is your favourite, a ‘desert island artwork’ if you like?

JC: there is a piece I drew back in 2010 that I have hanging above my bed. it is a piece about resilience and the quietness of solitude. I’ll bring that with me please.

DB: are there any other artists you’re currently fascinated with, and how do they feed into your work?

JC: I am heavily influenced by those who came before me. I have referenced many great irish and international artists in the work I create. contemporary artists who inspire and push my standards and work ethic are ron muek, kate tempest, christo, richard mosse, connor harrington & maser.

caslin’s influences include ron muek, kate tempest, christo, richard mosse, connor harrington & maser

joe caslin

happening this week! holcim, global leader in innovative and sustainable building solutions, enables greener cities, smarter infrastructure and improving living standards around the world.

street art (253)

PRODUCT LIBRARY

a diverse digital database that acts as a valuable guide in gaining insight and information about a product directly from the manufacturer, and serves as a rich reference point in developing a project or scheme.