growing up among the ‘onion fields and big skies’ of rural america, artist jacob hashimoto collected an open and abundant perspective. ‘it makes you see culture and cultural patrimony through an oddly shaped lens,’ he shares with designboom in this exclusive interview. half-japanese and half european american, and the son of an english professor and school administrator/social worker at a small liberal arts college in washington state, hashimoto considers his background hugely influential in terms of the way he thinks about art, its purpose and utility. ‘the work is generous because it is interested in speaking to as broad an audience as possible,’ he shares. ‘I’m always trying to create experiences and objects that cut to the core of all of our experiences of the world. it’s an overly broad and idealized goal, but maybe that’s what you get when all of your world were onion fields and big skies as a kid.’

across a mix of sculpture, painting, and installation, hashimoto creates complex universes from a range of modular components, including bamboo-and-paper kites, model boats, and astroturf-covered blocks. his richly-layered compositions reference technology, video games, and virtual environments, while also remaining firmly rooted in art-historical traditions and craftsmanship. ‘it’s about creating spaces for questions and thought and, when successful, it also reminds us of some fundamental things — the size and power of nature, smallness, sisyphean efforts, the kind cumulative experience of a lifetime. all of those things are built in to the work and I think that we experience those things as a community, often times through artwork, and through the discussion of those artworks. so, if any point my work happens to do that, I think it’s been very successful.’

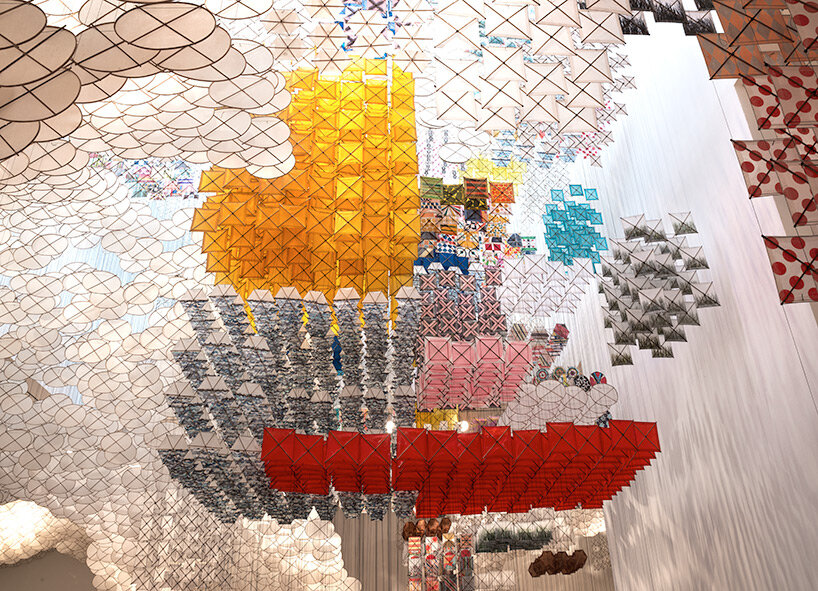

the eclipse, 2017- 2018 | bamboo, screen prints, paper, wood, acrylic and cotton | dimensions variable

st. cornelius chapel, governors island, NY

image by erin o’hara

designboom spoke with jacob hashimoto about how his upbringing has shaped his creative principles, the loss of materiality and traditional ways of making, and relying on the small things in life.

designboom (DB): we last spoke with you in 2012, and a lot has happened over the last decade — how has your work developed? what has changed for you?

jacob hashimoto (JH): I mean a lot has changed. we moved the studio out of new york city, which is probably the biggest change. we moved it to a small town on the hudson river just north of manhattan. I think the change to a small town environment has transformed the studio practice and the work in ways that were probably necessary. after so many years of working in cities, it’s healing to have a quieter, more focused studio. additionally, I had a daughter and that’s also hugely affected the way that I’m working quite a bit. I can’t work 24 hours a day anymore. all-nighters and months-long trips are also prohibitively difficult. so I’m much more focused when I go into the studio and I think it gives me a level of engagement that I haven’t had since I was much younger. obviously, overshadowing all of this is the COVID-19 pandemic, which has completely reorganized the ways that all of us have been able to work. we did OK with the virus and have many protocols in place around the studio, but it has definitely disrupted the creative rhythm of the studio. it’s been damaging, but hopefully we’re learning a bit too. right now, what we are doing is trying to re-build and reorganize the studio to kind of recapture some of the lost energy and productivity. also, I think the time is coming to try and process how the pandemic has changed how we work, what we work on, and who our audience is….among other questions. it’s still hard to see clearly what the studio practice is going to look like as we emerge from all of this into even newer normals. it’s hard to understand how it’s going to work, what kind of projects we want to explore, what the environment in the art world is going to look like. so many changes….we’re waiting like everyone else to see how it all plays out over the next few years. in the meantime, art making is a good way to help process.

the eclipse, 2017- 2018 | bamboo, screen prints, paper, wood, acrylic and cotton | dimensions variable

st. cornelius chapel, governors island, NY

image by timothy schenck

DB: what aspects of your background and upbringing have most shaped your creative principles and philosophies?

JH: well, you know, I grew up the son of an english professor and a school administrator/social worker. my folks both worked at a small liberal arts college in rural washington state (USA). I think that was probably hugely influential in terms of the way I think about art, its purpose and utility. I think that it also affects the things that I’m principally interested in creatively and what drives me professionally. growing up in the country was great but also vastly boring and I had a lot of time alone to work and stare into space…both good things if you want to work well in the studio. so, the practice of the studio has always been fundamental to my creative life. by that, I mean that the goal of making art is tied directly to the practice and life of making. I get up everyday and go to the studio and the art grows from that, sometimes frustrating, consistency. principles and philosophies are a bit difficult to parse without boring everyone, but, generally, I think that my work was shaped by growing up in the country and being socialized in an environment that wasn’t necessarily sophisticated or particularly worldly in their thinking about art.

counterintuitively, it was a huge benefit for my work and I think that it’s allowed the work to speak meaningfully to a broad audience that I might not have been able to access if I had grown up on more narrow social and intellectual circles. the work is generous because it is interested in speaking to as broad an audience as possible and through the work, I’m always trying to create experiences and objects that cut to the core of all of our experiences of the world. it’s an overly broad and idealized goal, but maybe that’s what you get when all of your world were onion fields and big skies as a kid – I’m joking a bit, but the kind of ideals that populate the work really do come from a certain youthful ignorance…and that’s probably a good thing to try and keep a hold on.

the eclipse, 2017- 2018 | bamboo, screen prints, paper, wood, acrylic and cotton | dimensions variable

st. cornelius chapel, governors island, NY

image by timothy schenck

JH (continued): of course, I could talk all day about how growing up in a liberal artsy household had an indelible and lasting affect on my artistic and personal philosophies and it did. the one specific and important thing that it impressed on me however was the importance and practice of lifetime learning. this is fundamental to any studio practice. and I think as an artist its always been important to me that the studio is a place of lifetime learning where I’m constantly teaching myself new things. the studio staff is constantly learning and teaching themselves new ways of working and creating. through this process the art’s philosophies, priorities, and purposes are also changing, reflecting that sort of autodidactic ethos.

finally, and importantly, I’m half-japanese and half european american and having grown up asian american – or at least half asian-american in a rural part of the united states definitely helped shape who I am as a person in ways that I think can’t help effect the way that I make my artwork. so my relationship with traditional materials and traditional japanese handicraft, you know a lot of that stuff is a product of my relationship to asian culture through the lens of being an american. it’s easy to get bogged down in all of the ways this may or may not have affected the ways that I think about artwork and I don’t think that there are many clear answers as to the specific impacts of growing up culturally isolated. it makes you see culture and cultural patrimony through an oddly shaped lens…and I think it’s, at times, useful.

the eclipse, 2017- 2018 | bamboo, screen prints, paper, wood, acrylic and cotton | dimensions variable

st. cornelius chapel, governors island, NY

image by timothy schenck

DB: you’ve described your work as ‘cultural landscapes’, representing different periods of time and parts of the world. how do you choose the narratives to weave into a single piece? are they typically personal to you, or do they respond to the context of the site in which they’re placed?

JH: I think it depends on which artworks specifically we’re talking about. very often, the artwork does both – the work is a balance between my personal narratives as they are shaped by the broader cultural, architectural, or intellectual context in which they’re placed. sometimes, for example, when I’m doing public artwork, the mandate of public art programs provide a certain framework, into which, I have to build my work. the goals and purpose of the artwork have to serve the need of the audience, the institution, and my own personal agenda — it’s always a bit of a juggling act. conversely or contrastingly, I think that when I make works in the studio the decisions are obvious — I don’t know if its obvious, but they are at least much more personal and a lot of times they come from things that I’m interested in or kind of mulling over in my intellectual life. I’m defining the audience and the narrative and planning the context without committee or institutional influence, so the process tends to be much more seamless. narrative responds to context as necessary to serve the purpose of the individual artwork within its own rules, it doesn’t compromise. that said, I think that it’s important for people to understand that the studio is a composite of lots of people’s voices, so while I control a lot of the narrative that goes along with the artwork, and I am the final editor, my studio assistants and staff also bring a lot of their own experience and creative input to the artwork. so a lot of what happens around here is that I’ll have this over arching sort of creative agenda, but underneath that umbrella, other people are doing what they’re interested in at that moment, and we have to figure out a way to bridge all of those voices together in order create something that’s more than the sum of its parts. I think that the process is a combination of my having control and having an agenda…and accepting that the rest of the world exists and other people have voices that add to the narrative of any individual artwork.

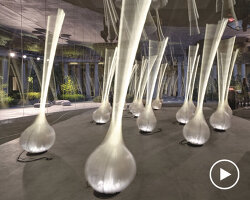

the city, 2020 | bamboo, resin, UV prints, screen prints, and fiberglass rod | 40’ x 30’ x18’

PDX- portland international airport, portland, OR

image by mario gallucci

DB: how planned is the configuration of each piece? is there room for spontaneity and improvisation while you’re working?

JH: I think spontaneity and improvisation are absolutely critical to the work. yeah, so the super short answer is that yes, there is room for spontaneity. the pieces themselves — to go back to how planned things are, each artwork has kind of a different degree of planning that goes in to it depending on my intentions for it. so for example, sometimes if there’s a certain pattern or specific sort of graphic architecture I’m interested in, I’ll be very calculated in my approach and we’ll start with drawings and build the pieces directly from reference drawings that are quite planned and prescribed. within those drawings there’s room for some chaos. other times there’s no drawings, no plans and I just have thousands and thousands of odd parts that I’m struggling to figure out. I kind of discover through making how they make sense. those pieces tend to be much more painterly and intuitive and immediate in terms of my relationship with them. and it works in large part because the system by which all the artwork is made is pretty prescribed, and so everything that I do in the studio either plays with the precision and repetition of the method of making or completely subverts it, breaks it, annihilates it and allows the body of work in general to have a lot of range — even though the method of making fairly prescribed.

the city, 2020 | bamboo, resin, UV prints, screen prints, and fiberglass rod | 40’ x 30’ x18’

PDX- portland international airport, portland, OR

image by mario gallucci

DB: in a world that is increasingly virtual, your work is rooted in tactile and physical experience. do you think society today is moving too far away from materiality, and traditional ways of making?

JH: I mean, I think society is always moving away from traditional ways of making. it’s inevitable. I feel like I worried for many years about this kind of loss, but these days, it seems like our control over such things is pretty much a lost cause. maybe it always is and it just takes time and living to begin to process the inevitability of change. I know that I’m interested in the kinds of things I’m interested in it because of who I am and when I am, but it’s hard to imagine my daughter seeing the world and processing materiality and traditions in the same ways. there’s certainly value to materiality and traditional ways of making, but I don’t expect them to go on forever. I think there will come a time when the society, broadly speaking, doesn’t see value to them. I think right now, the community of people that are interested in what I do are also interested in the traditions in which I’m working and they’re probably interested in handicrafts and traditional ways of making things. and, I think that we’re having kind of an interesting cultural discussion through the artwork because of that.

the city, 2020 | bamboo, resin, UV prints, screen prints, and fiberglass rod | 40’ x 30’ x18’

PDX- portland international airport, portland, OR

image by mario gallucci

JH (continued): in the future, maybe other artists not of my generation won’t see the value of working the way that I work. I don’t think it will diminish what they create artistically, it’ll just be different and I feel like that’s happened throughout the history of humanity. technology changes; those who are raised in certain technologies have certain values that those who were not raised with them don’t have. this goes on and on and on and the fabric of our expression, our poetry, and our philosophy changes from generation to generation. the one thing I’m very curious about is what’s happening with NFTs – and, clearly, I’m not alone in this curiosity – I’m curious about these non-fungible tokens, because I think that we are just seeing this new language come out, not even language, but this artifact that’s sellable, preservable, tradable. it’s this kind of purely digital object, that hasn’t really been possible pre-block chain and something that we really haven’t experienced before. I’m curious to see how that’s going to change or not change the way we make art or what we think about as an art object. in the back of my mind, I want them all to fail cause it rubs me the wrong way — to have this virtual trading card, this artificial currency might just be a stepping stone to a stepping stone to something else that is more interesting. right now, we’re just creating souvenirs of the pre-NFT world and it’s not hugely interesting but maybe these are just the first infantile steps towards creating something new or more interesting that I can’t personally see.

the city, 2020 | bamboo, resin, UV prints, screen prints, and fiberglass rod | 40’ x 30’ x18’

PDX- portland international airport, portland, OR

image by mario gallucci

DB: what impressions do you hope your work conjures? what discussions do you hope it provokes?

JH: I hope it provokes discussion. I think it’s always a huge achievement. art work lives in the world and lives through people’s experience of it and part of that experience is provoking discussion whether it be as fundamental as, ‘I like this more than I like that,’ or, ‘it makes me feel like this,’ or ‘this kind of this art is worthless,’ or ‘this is transformed the space architecturally in these kinds of ways, – what do you think? oh its brilliant oh it’s made it better,’ etc. being able to kind of invoke a discussion in a world of pretty apathetic people feels like a real achievement. I’m not personally super invested in the nature or specifics of the discussion. revelations and conclusions as they pertain to my art are fugitive because the work isn’t about delivering the absolute, it’s about being an open system that people can impress their own experience and reflect and validate ones own experience of the world. it’s about creating spaces for questions and thought and when successful, it also reminds us of some fundamental things — the size and power of nature, smallness, sisyphean efforts, the kind cumulative experience of a lifetime. all of those things are built in to the work and I think that we experience those things as a community, often times through artwork, and through the discussion of those artworks. so, if any point my work happens to do that I think its been very successful.

the sky, 2020 | bamboo, resin, uv prints, screen prints, and fiberglass rod | 40’ x 30’ x18’

PDX- portland international airport, portland, OR

image by mario gallucci

JH (continued): there’s something to be said about the nature of meaning that I’m constantly discussing with myself — the nature meaning’s changeability is worth some consideration, and I think that the kind of artwork that I try to make engages in this discussion as it exists in the world. it engages in the sense that its meaning and its purpose change as the society and world in which in it lives changes. I see things that I made decades ago that are completely transformed in terms of their meaning today. stuff happens and as it does, and because artwork lives in the world, the conversation around the work subsequently changes. context and signifiers and language itself change over time, the discussion itself changes, and that’s probably an interesting, if a bit self-indulgent discussion that we see in art and tons of other disciplines as well.

the sky, 2020 | bamboo, resin, uv prints, screen prints, and fiberglass rod | 40’ x 30’ x18’

PDX- portland international airport, portland, OR

image by mario gallucci

DB: also in our last interview, you shared a few of things that you were afraid of regarding the future, including a concern for art becoming too much of an industry. how do you reflect on that point of view today, and how do you asses the current state of art?

JH: I think that all of us are a bit uneasy about all of the changes that have taken place in our industry over these past years. I’m still always a bit worried about the huge growth of the art industry. it seems so unsustainable. I think there was some reasonable expectation that we were moving towards some sort of market adjustment in the last couple of years. COVID-19 gave us a bit of an abrupt, non-art world specific adjustment and I’m not confident that anybody knows how all of it is going to play out over the coming years and months. a lot of the fundamental problems with the art market still exist despite the global shutdown. I think that it would probably be foolish for me or anyone else to make any sort of predictions on how things will look like this time next year for the art world and the art market and art in general. seems like there are a lot of variables and unknowns.

the sky, 2020 | bamboo, resin, uv prints, screen prints, and fiberglass rod | 40’ x 30’ x18’

PDX- portland international airport, portland, OR

image by mario gallucci

JH (continued): however, I do think lots of people who grew up in the 80’s and experienced the crash in the late 80’s have a bit of nostalgia for a time when nobody had a career. post-2004 we all know how much things have grown – the internet, phones, digital imaging, fair culture, auction houses have all allowed for exponential market growth and I think the art itself has probably suffered a bit. I know that this last year has been really hard on a lot of artists, galleries, and museums and I think that we’re all clearly waiting to see how this will impact artistic production moving forward. some of the pre-COVID problems with gallery consolidation and closures, fairs, and museums are still in play and it’s hard to see how or if that will have an impact on artists. the ground is very uneven out there and I fear there will continue to be a collapse in the emerging arts and a stultification in the establishment art community. as to how all of this affects the state of art? who knows. change is afoot however. be it through COVID, global climate change, violence, inequity, things feel ready to break in some fashion.

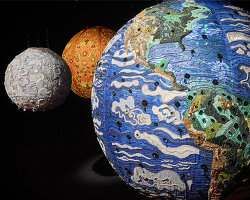

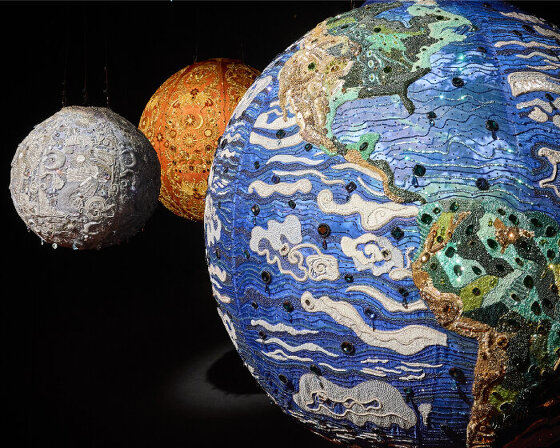

gas giant, 2014 | bamboo, paper, acrylic, wood, and cotton | dimensions variable

MOCA pacific design center, los angeles, CA

image by fredrik nilsen

JH (continued): in this stage in my career, you know, a decade or so on from our last talk, I just need to make some decisions about what kind of work I want to make, and how I want to participate with the market. the art market is going to do whatever it’s going to do. understanding yourself well enough creatively to understand you know what you want to make, and how you want it to be presented, and how you want it to exist in the world I think are individual decisions at this point. I think the art market itself will get bigger and bigger and bigger until it faces a pretty major adjustment and then it will probably reset and get bigger and bigger and bigger again until it can’t anymore. it’s not something that I think I personally have a lot of control over or ever did. so I guess I’m not as worried as I used to be even though I should be.

gas giant, 2014 | bamboo, paper, acrylic, wood, and cotton | dimensions variable

MOCA pacific design center, los angeles, CA

image by fredrik nilsen

DB: what are you currently fascinated by, and how is it feeding into your artistic practice?

JH: not to be flip, but my lack of fascination is a bit fascinating when I think about it. we’re always looking to creative folks for inspiration and to see what they’re looking at or thinking about….but these days have been hard. it’s hard to look out at the world for inspiration and it’s hard to look at history as a guide to navigate these unsettled waters – it all seems borderline irrelevant. I’m not all doom and gloom, but I think that we’re probably at a moment when looking at traditional forms for inspiration is a bit of a waste of time. you know TV has gotten so boring and repetitive. we’re sitting around wondering if there’s some possible way to resurrect all of the avengers because creating new mythologies out of whole cloth is way too exhausting to consider. I think it’s probably a symptom of the pandemic lock down. everything tastes like dirt. so it’s a difficult moment for everybody.

gas giant, 2014 | bamboo, paper, acrylic, wood, and cotton | dimensions variable

MOCA pacific design center, los angeles, CA

image by fredrik nilsen

JH (continued): I’m also fascinated by the fact that everybody is interested in what artists are thinking during this time. people are talking about it like its sort of a sabbatical from the world that artists are taking — like it’s supposed to be some incredibly fruitful moment. it’s curious that people have these expectations of artists that they don’t have for the rest of the community when we’re all just a bunch of people trying to get through the day, everyday.

for me, practically, I rely on small things in life and in the studio to feed the work, momentary fascinations. I’ve been drawing more and riding my bike and taking time to think and work on small problems within each work. I think I’m trying to figure out how to get by, get up and do my work, and stay interested in these small momentary things and not cripple myself with too much ambition.

the unbroken grace of perplexity and madness, 2020

bamboo, paper, acrylic, wood, and dacron | 45” x 74 7/8” x 8.25”

galerie forsblom, helsinki,FI

image courtesy of jacob hashimoto studio

the unbroken grace of perplexity and madness, 2020

bamboo, paper, acrylic, wood, and dacron | 45” x 74 7/8” x 8.25”

galerie forsblom, helsinki,FI

image courtesy of jacob hashimoto studio

this infinite gateway of time and circumstance, 2019

paper, UV ink, resin, bamboo, spectra, acrylic, stainless steel | 9’ x 39’ x 9’

SFO- san francisco international airport, san francisco, CA

image courtesy of the san francisco arts commission

this infinite gateway of time and circumstance, 2019

paper, UV ink, resin, bamboo, spectra, acrylic, stainless steel | 9’ x 39’ x 9’

SFO- san francisco international airport, san francisco, CA

image courtesy of the san francisco arts commission

this infinite gateway of time and circumstance, 2019

paper, UV ink, resin, bamboo, spectra, acrylic, stainless steel | 9’ x 39’ x 9’

SFO- san francisco international airport, san francisco, CA

image courtesy of the san francisco arts commission

the dark isn’t the thing to worry about, 2018 | bamboo, paper, acrylic, wood, and dacron | dimensions variable

SITE santa fe, santa fe, NM

image by eric swanson photography

the dark isn’t the thing to worry about, 2018 | bamboo, paper, acrylic, wood, and dacron | dimensions variable

SITE santa fe, santa fe, NM

image by eric swanson photography