inside the uzbekistan pavilion at the 60th venice art biennale

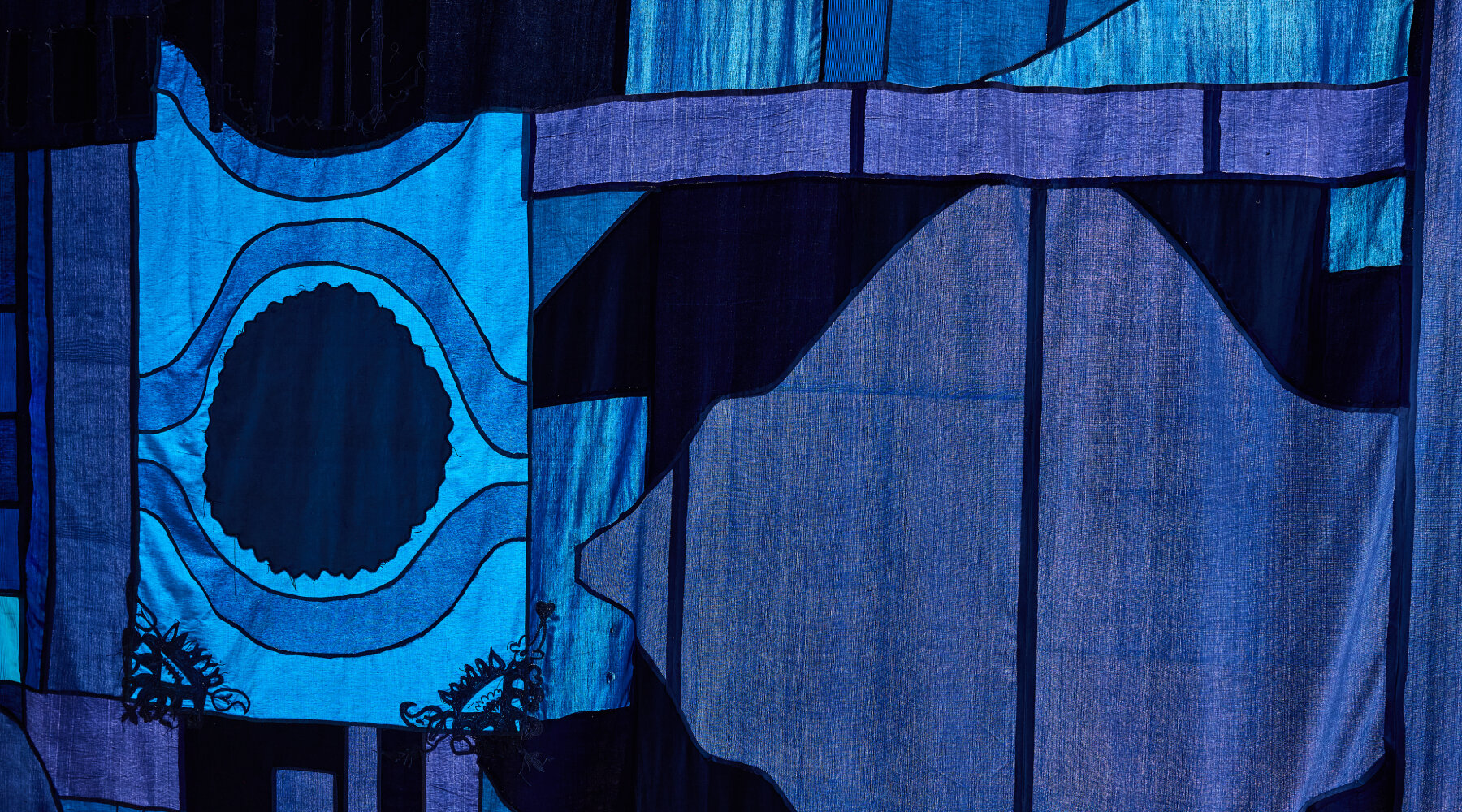

Wading through hues of blue, patchwork tapestries, and suzani embroidery, the Uzbekistan Pavilion at the 60th Venice Art Biennale is a theatrical staging of collective voices and cultural memory. Artist Aziza Kadyri turns the pavilion, titled Don’t Miss the Cue, into a deconstructed backstage of a theater — a dimly lit room with hidden corners, lined with heaps of costumes, reconfigured hanging rails, and digital screens. Visitors wind through a sensorial yet obscure journey that culminates as they emerge onto an open stage illuminated by spotlights and activated by the gaze of resting ‘audience’ members — a nod to Kadyri’s background in theater.

Speaking with designboom, the artist reflects on how this concept is one that is both deeply personal and representative of the collective experiences of Central Asian women. ‘When representing a country,’ she shares, ‘it’s crucial to bring in a multiplicity of voices, especially those that are often underrepresented, like the younger generation of women who grew up after Uzbekistan’s independence in 1991.’ Kadyri then worked closely with the Qizlar Collective (Qizlar meaning ‘girls’), a group of female artists giving a stage to the narratives of these women, translating their postcolonial memories in search for identity, and their resilience, into poetic design installations. The works as such urge reflection and interaction, even inviting visitors to step inside the textiles and embody their weight. ‘The whole idea is to transmit a bodily sensation — a sense of corporeality. The audiovisual elements also attempt to represent these experiences of the community in a more indirect and emotional way,’ Kadyri adds. Read on for our full conversation.

all images courtesy of ACDF

a journey through a deconstructed theater backstage

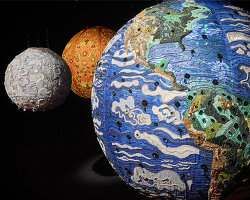

Though part of the Uzbek diaspora herself, Aziza Kadyri further looks to her heritage to question what it means to be a creative working with traditional practices today. In collaboration with master embroiderer Madina Kasimbaeva who has been working with embroidery for 25 years, she reimagines artisanal forms with technology at the Uzbekistan Pavilion. AI, an increasingly prevalent tool within our contemporary creative fabric, is trained to reinterpret an archival body of suzani patterns which Kasimbaeva with her team materialized across the pavilion’s hanging curtains and embroideries — their forms oscillating between past, present, and future.

Notably, for both the artist and the artisan, technology is not at odds with tradition. While Kadyri likens Uzbek suzani works to historical documents and their associated processes as a record of female collectivity, AI becomes a modern tool to remember and reinterpret them for contemporary contexts. The integration of AI, which the artist refers to as a globalized ‘vessel for collective memory,’ modernizes the visual language of the patterns to strengthen their resonance with newer generations. ‘During our discussions, Madina mentioned that some patterns didn’t reflect her experience as a woman in the 21st century. Then conversations ensued that sparked a search for innovation — how it’s okay to break from tradition and create something that represents your current reality,’ the artist tells designboom. Read the full interview below.

the Uzbekistan Pavilion at the 60th Venice Art Biennale

aziza kadyri on collective memories at don’t miss the cue

designboom (DB): Your representation of your nation brings together a range of voices in the community, heritage, and traditions. Can you begin with introducing these collaborations?

Aziza Kadyri (AK): Initially, I was asked to do a solo, but a lot of my practice is collective. When representing a country, it’s crucial to bring in a multiplicity of voices, especially those that are often underrepresented — like the younger generation of women who grew up after Uzbekistan’s independence in 1991. So, I invited the Qizlar Collective, which I co-founded, to join me in this project. We focused on the experiences of young women within our community, especially how life has changed post-independence.

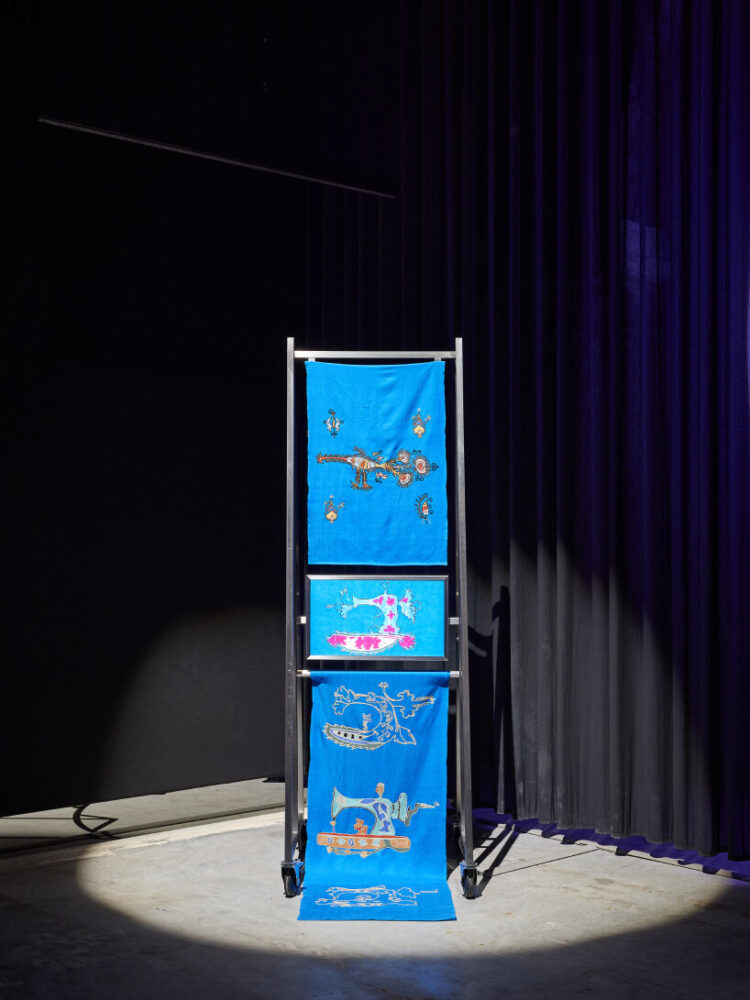

We also worked with a fantastic artisan embroiderer, Madina Kasimbaeva. This ties into another strand of my practice, where I explore the visual language of embroidery as a historical document, a way women recorded their hopes and dreams over the centuries. We wanted to modernize that tradition, to reimagine it using contemporary technology.

a theatrical staging of collective voices and cultural memory

DB: What inspired this spatial concept of an abstract experiential journey ending upon a stage?

AK: I came up with this idea of a deconstructed backstage of a theater, which draws from my experience of traveling through different countries by working in theaters. I’ve worked as a theater designer, scenographer, and costume designer for a long time, and I think those traces of storytelling persist in everything I do.

Backstage, to me, became a metaphor for this collection of disparate objects. When you go backstage, you find costumes from one play and props for another, all bunched together. They somehow tell a story, even if it doesn’t make immediate sense. That process of picking up pieces — of identity, of memories — feels similar to what I and many of the women we spoke to have experienced. In this way, my work is also very performance-focused, but it’s never direct. I feel that putting things poetically actually communicates more, and that’s something we tried to capture with the pavilion.

Don’t Miss the Cue welcomes visitors into a deconstructed backstage of a theater

DB: Do these ideas of migration and performance extend to the visitor experience too?

AK: I design experiences, and my theater background, along with my work in immersive experiences and technology, drives me to create specific emotional responses at certain moments. There’s a twist to the journey of walking through the works in the dark because you go through, then you’re suddenly on stage, with people staring at you. Here, I wanted people to feel a sense of discomfort, something they could either accept or reject. They could either step off the stage or become one of the ‘performers’.

wading through hues of blue, patchwork tapestries, and suzani embroidery

DB: How do the works on display speak to these themes of theater and interactivity?

AK: There are interactive stage costumes and metal structures along the journey, these hanging rails, that form and deconstruct shapes reminiscent of familiar spaces in Uzbekistan, like a street lamp with seating areas.

It was our attempt to translate the experiences we gathered from interviews with different women, finding similarities between their stories. These installations embody their memories. So, when you step into a costume, you might get a sense of how their bodies felt at certain moments in their lives. The whole idea is to transmit a bodily sensation — a sense of corporeality. The audiovisual elements also attempt to represent these experiences of the community in a more indirect, poetic, and emotional way.

the journey ends as visitors emerge onto an open stage illuminated by spotlights

DB: We also see a lot of traditional embroidery and motifs. In bringing together artisanal practices and new technologies such as AI, how do you relate the results to identity, heritage, and collective experiences?

AK: I worked closely with Madina Kasimbaeva and something she said really stuck with me. That suzani embroidery is one of the first, and most known practices reflective of women’s collectivity in Central Asia. Women always embroidered together, it was rarely an individual effort. Each piece they created became part of a collective expression. But then I also have this interest in AI as a vessel for collective memory but in a more globalized sense. Over the past 25 years, for instance, we’ve created so many images, and they now form a pool of knowledge that remembers for us.

I wanted to see how AI and traditional craft could interact. So, I trained an AI on my own archive of patterns, and instead of giving it words, I’d input a specific design, like one with a circular motif from Samarkand which represents an astral body. I’d let the AI interpret it back to me, and it would poetically transform the pattern into something new. I’d then show these outputs to Madina, asking if they resonated, and the women working in her studio were so intrigued by the idea of using traditional techniques to create something completely out of the box.

Aziza Kadyri looks to her heritage to question what it means to be a creative working with traditional practices today

During our discussions, Madina mentioned that some patterns didn’t really resonate with her anymore. They didn’t reflect her experience as a woman in the 21st century. Then conversations ensued that sparked a search for innovation — how it’s okay to break from tradition and create something that represents your current reality. It’s been a truly collaborative process between artist and artisan, and I’ve learned a tremendous amount from her.

the textiles by Madina Kasimbaeva materialize AI speculation

DB: The pavilion is deeply rooted in your identity, and reflective of those you worked with. How did you hope the concept, staging, and exhibited works would be received by visitors?

AK: Whenever I work on a project, I always formulate an ideal audience. For this pavilion, I envisioned younger people from diasporas or who have experienced migration – people a little like me. I wanted to connect with them on a deeper level.

While the experiences and stories we share from Uzbekistan are very specific, there’s something universal about them. Almost everyone has experienced migration in some form, even if it’s just moving to a new town. The emotions we convey are universal. Many people didn’t really understand it. But I also received so many messages from people telling me how moved they were by the pavilion.

the Uzbekistan Pavilion’s concept reflects the collective experiences of Central Asian women

DB: You have a very memorable and bold title: Don’t Miss the Cue. What does this mean?

AK: It’s from the phrase ‘Don’t miss your cue’, which is said to actors when they’re about to go on stage, and that obviously ties into the theatre form that we’re working with.

But there’s also a wordplay because we can talk about social cues, which directly ties into gender socialization and how women navigate social scripts to advance through the world.

I’m really proud of the title. It’s punchy, playful, imperative, and invokes this fun curiosity. And it really fits the journey we’re winding visitors through, ending with them under a spotlight on the stage. What’s interesting is how the stage has inspired spontaneous performances. Audiences have started clapping when others step out, and it’s also led to impromptu dances, poems, and other performances. The space is activated by the audience.

a dimly lit room with hidden corners, lined with heaps of costumes, reconfigured hanging rails, and digital screens

the costume installations invite visitors to step inside

Aziza Kadyri draws on her background in theater

the Uzbekistan Pavilion is shaped by collective voices and traditions

project info:

name: Don’t Miss the Cue

artist: Aziza Kadyri | @aziza.kadyri

collaborators: Qizlar Collective, Madina Kasimbaeva

location: Uzbekistan Pavilion, Arsenale, Venice

program: Venice Art Biennale 2024

on view: April 20th – November 24th, 2024

curator: Institution of the Centre for Contemporary Art Tashkent

commissioner: The Art and Culture Development Foundation

happening now! thomas haarmann expands the curatio space at maison&objet 2026, presenting a unique showcase of collectible design.