ghanaian artist ibrahim mahama repurposes discarded materials from urban environments into artworks that explore themes of commodity, globalization, migration and exploitation. his monumental installations are made from materials such as remnants of wood, or jute sacks, which are stitched together and draped over architectural structures. born in tamale, ghana, in 1987, the artist currently works in accra, kumasi, and tamale, where he also recently opened SCCA tamale, an artist-run space dedicated to retrospectives of practices which emerged from the 20th century. designboom spoke with ibrahim mahama during design indaba 2020. read the full interview below.

a friend, 2019 by ibrahim mahama at caselli daziari (tollgates) di porta venezia, milan

a friend, 2019 by ibrahim mahama at caselli daziari (tollgates) di porta venezia, milan

designboom (DB): can tell us about your background? how did you go from painting to spatial installations?

ibrahim mahama (IM): I studied at the kwame nkrumah university of science and technology in kumasi ghana. our teachers had also trained within the same college but from a much older curriculum. it didn’t allow for experimentation or enough freedom within artistic practice so they said to themselves, ‘we can’t teach these same things,’ and they became interested using pedagogic revolution as a way to shift ideas and forms within our generation. they started teaching things like philosophy, which was not being taught, critical and analytical thinking, using other subjects like science, math or any discipline as a source of inspiration; and the curriculum changed significantly. I enrolled in the university for my undergrad in 2006 and I was fortunate have these mentors. one important character was kąrî’kạchä seid’ou, a lecturer at the department of painting and sculpture. he later became a mentor and he is an incredibly good thinker, and his idea was, ‘how can we transform art itself or make it a gift to society?’. art should always be what we imagine tomorrow to be in terms of form, reality or experience – that’s what I took from there art school. I started thinking about everything as an artistic form, and now you see me using airplanes, or trains. lately I’m working on a project to create these merry-go-rounds for kids within the community as part of my studio project in tamale redclay. the idea is, ‘how do you create a work of art that becomes an experience, something that lifts other people, and it’s not something that is commodified’. but at the same time the paradox of the art world allows for these projects to be possible, I don’t take anything for granted but then if you take that same idea and translate it into the world, particularly in a given context, you can change so much within it. the world needs change but we have to create systems which are fundamentally un-suppressive and allow for free thinking and justice for all. the ideas and history of painting is really expansive, we just want to extend the forms they have always claimed to have proposed. in the time of crisis, we have to use the conditions which define our reality to reinvent our experience of the world. malam dodoo national theatre 1992 – 2016. covering of the national theatre of ghana in charcoal jute sacks in 2016 as part of the exchange exchanger project

malam dodoo national theatre 1992 – 2016. covering of the national theatre of ghana in charcoal jute sacks in 2016 as part of the exchange exchanger project

DB: so what happens with your artworks once the show is over? do you reuse them, or sell them?

IM: I don’t sell those installations, I reuse them. sometimes they travel from place to place as if they were collecting memories and residues. for instance, some of those works have gone to sydney, where I’m going from here for the 22nd sydney biennale. the installation will be at the cockatoo island in sydney, where they have these huge spaces. these are old factories which were used for making ships back in the 20th century. we’ve covered the entire interior of this space, and these materials are the same which were used in venice biennale, documenta 14, K21 in dusseldorf and many other projects. so they almost become like clothes, they move from one body to the other, and as they move they take histories and scares with them for new conversations. K.N.U.S.T library. occupation and labour 2014. K.N.U.S.T kumasi ghana

K.N.U.S.T library. occupation and labour 2014. K.N.U.S.T kumasi ghana

DB: one of the main materials you use, jute sacks, has a history that is directly connected to the history of ghana, but then it’s interesting that you apply them to other places beyond ghana. what kind of contexts are you looking for when you decide to use them in another location? because I saw your work in syntagma square in athens, greece during documenta 14, and I thought it was interesting how two kinds of contexts can co-exist.

IM: it’s not only in relation to history, but also in relation to the crisis, I always thought that art is born out of crisis. so what do those aesthetics have in common? for instance, the jute sacks typically represent exploitation of commodities around the world; all the coffee, cocoa we drink around the world, doesn’t come from the so called first-world countries. also, ivory coast and ghana alone produce over 70% of the world’s cocoa. by the end of the year the value for cocoa that is produced out of such commodities is about 150 billion dollars but between ghana and ivory coast, they make around 2 billion dollars, which means there are no processing plants for transforming these commodities they produce. it’s something heavily embedded within a certain political and economic system. in the early 1960’s kwame nkrumah had the idea to build these silos in ghana for the storage of food, but it has never been realized since his over throw in 1966. the west typically didn’t want it because of the economic implications it was going to have on trading. it’s the same thing when you look at economies around the world. the jute sack, at its lowest level, somehow represents all of this, it begins to reveals the inequalities within an established system. if you go deep down into the microscopic level of the material, in terms of what its aesthetics produced, from there you can see that it relates to the protests in greece for the austerity measures, privatization of natural human resources, like water, which is supposed to be a common right we all share and so I think the idea of politics is somehow embedded within this material. check point prosfygika. 1934-2034. 2016-2017, documenta 14, syntagma square, athens, greece

check point prosfygika. 1934-2034. 2016-2017, documenta 14, syntagma square, athens, greece

DB: can you tell us a bit more about one of your recent works, the parliament of ghosts?

IM: I started making the parliament of ghosts last year, as a work of art. I was interested in it some years before but it wasn’t called the parliament of ghosts then, it became that when I designed it for the manchester international festival. the original idea was to transport two old locomotives from ghana to manchester together with other objects, like cabinets, to create these spaces around the city for both play and critical reflection. the locomotives of course couldn’t happen, but the cabinets and the seats could, so the parliament of ghosts was born. normally for an exhibition you make paintings or sculptures, but I wanted to create a work that was a place where people simply seat and have a conversation. but not just any conversation, because the parliament of ghosts is made of wood that was used in the last 130 years as well as cabinets for workers and railway slippers – the trains of exploitation – seats that normal people sat on, commuting to work everyday. if you’re creating a parliament with these kinds of materials, what kind of conversation do you think is going to happen within this chamber? for me that’s where the point is. the fact that the traumas and the failures of history itself can be a starting point to create a spotlight, and so now let’s start the conversation.

the ghosts are not necessarily from the dead but also an unrealized future which is constantly haunting us. it doesn’t need an audience to be complete, it is what it is. the aesthetics and physical states of the components making up the parliament speak volumes to the conversations which will be generated within it. in manchester, the parliament was used for all kinds of events from a fashion show to a meeting hall by school kids. the idea is for it to do more in the future when it takes other forms.

parliament of ghosts at the whitworth gallery, manchester as part of the manchester international festival in 2019

parliament of ghosts at the whitworth gallery, manchester as part of the manchester international festival in 2019

DB: and you have a second version of it in ghana, right?

IM: yes, I do. the parliament of ghosts was later developed as a central part of my studio (redclay) in tamale. unlike the artwork produced for the whitworth gallery as part of the manchester international festival, the parliament in tamale is permanent in its position as it was designed into the foundation of the institution. it will seat over 300 people at each point in time and there is a lot more detail than the piece which was presented in manchester. it was an important decision to situate the work there not only to amplifier the kinds of social transformations which would happen as a result of that but also simply produce artworks for ourselves rather than institutions. the idea is for this to inspire building of more local institutions ever more even within the difficult times and conditions we find ourselves.

the parliament of ghosts is a shift towards building spaces as a practice within our generation rather than relying modes of showing art within the traditional art world. artworks can be made specific spaces and communities within our local context rather than constantly exporting ideas all the time for mega exhibitions abroad. at the same time, we should also allow old sites to inspire us to create forms which go back to bring those sites back to life and offer renewed experiences.

this parliament will be used for lectures, as a classroom, cinema hall and exhibition hall for site specific installations through invited artists. I am sure many other ideas will develop once its put to use.

the parliament of ghosts. work in progress. as a central part of redclay. when completed, it will host artists talks, lectures, film screenings, community debates and meetings and also serve as a classroom amongst other functions

the parliament of ghosts. work in progress. as a central part of redclay. when completed, it will host artists talks, lectures, film screenings, community debates and meetings and also serve as a classroom amongst other functions

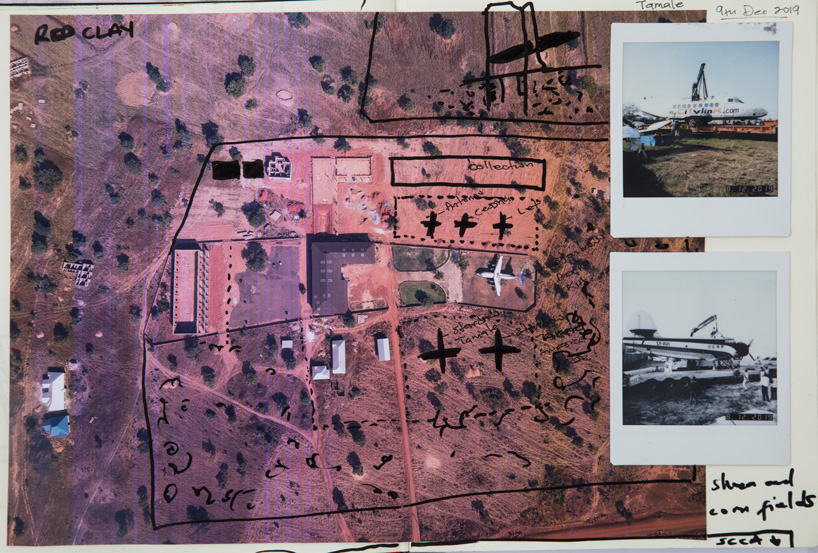

DB: you are also the founder of a project space, the savannah centre for contemporary art in tamale, ghana, and you showed in a video these airplanes that you were transporting through the city. what do you use these for?

IM: if you take out all the seats from an airplane, there is a perfectly good space for a classroom, with a few cabinets and desks there is a system to work with. some of these cabinets are coming from the ghana railways company while others from old factories from the 1960’s and also public schools. they are historical materials; which children will now engage with. I am presenting a 130 year, or 50-year-old desk to a child, who is now going to use it as a platform for drawing and is aware of its history, where it’s coming from, and what it’s built upon, from the starting point, his or her thinking will be different. we need social transformation through significant shifts within our ideological beliefs. I believe that is what will change the course of history within our life time. the seats that we removed from the airplanes will be used to build a series of cinema halls for screening both local, experimental films amongst many others. this is just one way to bring life back into the cultural scene aside that the physicality of the airplanes do something to the landscape which can also reshape the relationship between agricultural practices and the institution.  redclay jenakpeng, tamale ghana. work in progress. artist studio, library, cinema hall, exhibition halls, archives, photography lab, sound recording studio, parliament of ghosts, classrooms, residencies, farms and parks and museum of contemporary art

redclay jenakpeng, tamale ghana. work in progress. artist studio, library, cinema hall, exhibition halls, archives, photography lab, sound recording studio, parliament of ghosts, classrooms, residencies, farms and parks and museum of contemporary art

DB: what’s next?

IM: after the biennale of sydney, which is in a couple of days, I have a few exhibitions this year, quite a lot in europe. I have a group show in paris, then I have a solo show at the white cube in bermondsey, london, a group show in antwerp with the middlehiem museum, but I believe most of these will either be pushed to a much later date or even next year due to the current health crisis.

I will also go back to work on SCCA tamale/redclay with my colleagues in ghana. we are currently working on our next major retrospective on the ghanaian artist agyeman osei which is due to open in may this year but we might have to reschedule the opening date due to the current health crisis. our institution is working closely with blaxTARLINES kumasi, exit-frame collective and FCA ghana on these future projects. there is a lot of work to be done within our generation.

the savannah centre for contemporary art (SCCA) in tamale, ghana

the savannah centre for contemporary art (SCCA) in tamale, ghana  exchange exchanger. liberty please no enter by police, kanda 37, accra ghana

exchange exchanger. liberty please no enter by police, kanda 37, accra ghana wagon. site of production. sekondi locomotive station, 1901 – 2030, western region, ghana

wagon. site of production. sekondi locomotive station, 1901 – 2030, western region, ghana  K.N.U.S.T catholic church. site of production, 2016, kumasi, ghana

K.N.U.S.T catholic church. site of production, 2016, kumasi, ghana redclay jenakpeng, tamale ghana. work in progress. artist studio, library, cinema hall, exhibition halls, archives, photography lab, sound recording studio, parliament of ghosts, classrooms, residencies, farms and parks and museum of contemporary art

redclay jenakpeng, tamale ghana. work in progress. artist studio, library, cinema hall, exhibition halls, archives, photography lab, sound recording studio, parliament of ghosts, classrooms, residencies, farms and parks and museum of contemporary art

is a multifaceted platform committed to a better world through creativity. the south-african online publication hosts an annual festival and social impact do tank in cape town. the design indaba festival has been created by ravi naidoo in 1995, with focus on african and global creativity, through the lens of the work and ideas of leading thinkers and doers, opinion formers, trendsetters and industry experts.

happening now! in an exclusive interview with designbooom, CMP design studio reveals the backstory of woven chair griante — a collection that celebrates twenty years of Pedrali’s establishment of its wooden division.