kurt schwitters’ merz barn in cumbria to become art residency

Reviving a major remnant from the anti-art Dada movement, Factum Foundation has acquired Kurt Schwitters’ Merz Barn in England’s idyllic Lake District with plans to regenerate it as part of a creative cultural hub and art residency. The great German artist, who led a life of displacement and upheaval, is most recognized for his ‘Merz Picture’ collages created from discarded, found materials that he reassembled as a reflection on the fragmentation of his times. In 1937, Schwitters fled the Nazi regime and eventually found refuge in a barn in the Cumbrian countryside in which he lived and worked until his death in 1948. This space, though incomplete, became one of the most major artworks of his career and reflects his abstraction techniques and non-conformist ideologies in a new dimension. What remains is a spatial translation of his collages materialized through layers of plaster cast and painted over found objects.

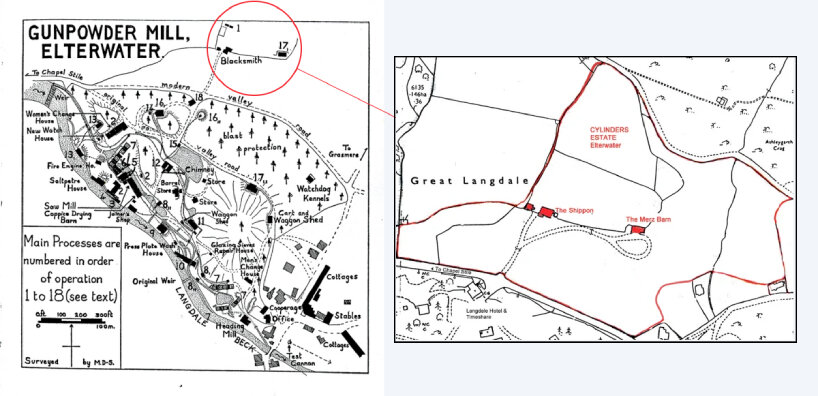

To learn more about the project, designboom spoke with Adam Lowe, founder of London- and Spain-based Factum Foundation. Lowe, who has long been committed to the preservation of Schwitters’ legacy, explains how he approaches at-risk cultural heritage sites by recording and replicating them through meticulously developed systems of digital technologies. At the Elterwater Merz Barn, this begins with creating a 3D digitization of the original wall, planning the reunification of the 3D collage with the site by creating a facsimile of the missing section. ‘We want to make sure the facsimile keeps the original intent, and that all aspects of Schwitters’ work are celebrated across all the other buildings on Cylinders with events that contextualize it,’ Lowe tells designboom.

entrance to the Merz Barn | image © Adam Lowe | Factum Foundation

interview with factum foundation’s adam lowe

designboom (DB): Can you introduce us to Factum Foundation and its broader initiatives?

Adam Lowe (AL): Factum Foundation was set up in 2009 to develop and apply digital technologies for recording and replicating cultural heritage sites and artifacts, and to build bridges between digital and traditional craftsmanship. Since then, it has worked all over the world, in some of the most prestigious museums as well as in places where cultural heritage is at risk, with a particular focus on transferring skills and technologies to local communities.

DB: You have been working with preserving Kurt Schwitters’ legacy for a while now. How did this acquisition of the Cylinders Estate and the pending restoration of his Merz Barn come about?

AL: I was invited to get involved in the Merz Barn at Cylinders by Richard Hamilton in 2008. We worked with Littoral Trust to make a facsimile of the Merz Wall and talked to the Hatton Gallery, and in 2009 we visited Norway, digitized and made a facsimile of the Schwittershytte in Hjertoya — which is today at the Henie Onstad Art Centre near Oslo. Celia Larner, who worked with Ian Hunter to preserve the site since 1998, requested assistance in taking the Merz Barn last year. We haven’t started any restoration yet, but the process will involve the barn, the buildings on the site, and Harry Pierce’s garden.

the Merz Wall installed at Hatton Gallery | image © John Lord | used under CC BY 2.0 | color edited

DB: How are you approaching the restoration and the creation of the facsimile here? You have been using digital technologies in really interesting ways to preserve so many historical artifacts and architecture across the world.

AL: It will first need an agreement with Hatton Gallery and the full digitization in 3D and color of the original wall, on condition we can use the data to make one facsimile for the Merz Barn at Cylinders. The data will be given to them. After this it will be a process of research and for this we will need the help of several people. Fred Brooks immediately comes to mind: he has been connected to the Merz Barn since 1965 and was part of the team from Newcastle University that made the survey of the Merz Wall and prepared its removal, moved it, and installed it in the Hatton. He told me that he ‘carried out extensive repairs and restoration on the artwork in its new home in the Hatton Gallery’. Moving a fragile plaster construction with the wall was a very complex task. We will also need to work closely with Derek Pullen who carried out the recent restoration of the wall at the Hatton Gallery and has a deep understanding of its materiality.

Our aim is to rematerialize the wall in ways that reveal Schwitters’ intentions, and for this we will rely heavily on Celia Larner, who spent many years looking after Cylinders and has an intimate knowledge of the site and its history. Our intention is to meet and talk to people who knew Harry Pierce (the owner of Cylinders and designer of the garden), Jack Cook (who assisted Schwitters while making the wall), and Edith Thomas (also known as Wantee, Schwitters’ partner).

Paul Thirkell, Derek Pullen, Steve Hoskins, and Adam Lowe viewing the Schwitters Merz Barn installation in the Hatton Gallery | image © Ian Hunter, Littoral Trust

DB: This space was used by Schwitters in exile, and the works are deeply personal expressions of his struggles. How will you preserve this essence, while finding a balance between making such a private work open for public engagement?

AL: The Cylinders Estate is a resonant location for the perseverance of art in the face of conflict, and Schwitters’ Merz Barn is an act of defiance by a refugee artist at the end of his life. It was made in a remote rural location, but it deserves to be a centre of attention. We don’t have all the answers, but if we ask the right questions and work in the right way, they will emerge.

We don’t want Cylinders to be judged by visitor numbers, but by depth of experience of those who visit. We have stated we also want it to be a refuge for refugee artists wanting to be in rural environments.

DB: Will the project embrace Schwitters’ approach of working with everyday materials?

AL: We won’t be improvising or altering the Merz Wall when we make the facsimile, but we will be undertaking a digital restoration using references such as Ernst Schwitters’ photo, taken soon after his father’s death. We want to make sure the facsimile keeps the original intent, and that all aspects of Schwitters’ work are celebrated across all the other buildings on Cylinders with events that contextualize it. The Lake District isn’t just spectacularly beautiful: three great radicals Wordsworth, Ruskin and Schwitters lived at different times just a few miles from each other!

the cluster of the remaining buildings from the charcoal works at Cylinders | image © Adam Lowe | Factum Foundation

DB: Do you also see any opportunities to integrate other multimedia art forms or expressions into this new experience?

AL: Yes — but anything we do will be the result of research and building consensus among those invested in Schwitters. We want Cylinders to become a place that celebrates Schwitters’ life in England and all aspects of his creative energy.

DB: Can you share anything some of the long-term visions for how the site will be used to engage both the public and art communities?

AL: There is a lot to be done — a lot to be understood and a lot of thought-provoking research to be carried out. We want to work with other local charities, and we will need support from philanthropic individuals, institutions, government agencies, and artists. Littoral Trust benefited from the generosity of artists including Damian Hirst, Anthony Gormley, and the Boyle Family. Many more will now be needed to make this vision of the site a reality. Our aim is to celebrate all aspects of Schwitters and the site — that will include Harry Pierce’s Garden, the history of the Langdale Hotel across the road, and the connections to Wordsworth, Ruskin, and others.

point cloud of the exterior of the Merz Barn following a first photogrammetry survey | image © Factum Foundation

DB: Looking ahead, how do you envision Factum Foundation’s work influencing future approaches to art and cultural heritage preservation?

AL: Factum Foundation is working to shape how technology can be used to preserve, communicate, and share cultural heritage. I invite people to lose themselves in Factum Foundation’s website, follow our newsletters, and read our publications. It’s a very exciting moment that is revealing the importance of culture in many forms. Our work ranges from Schwitters to tombs in the Valley of the Kings, from Michelangelo and Raphael to the Sacred Cave of Kamukuwaká (that is being installed in the Amazon as I wrote this).

A team is just back from recording in Mexico, a team is traveling to London to work at the British Museum, and another is in Venice. Culture has never had so much to offer to so many people — our aim is to make sure that those who are interested can find a point of access. Please look at Factum Foundation’s last publication… it’s packed with examples that show significant changes in the way we preserve both nature and culture are taking place right now. Schwitters’ Merz Barn in Elterwater and Aalto’s Silo in Oulu are just two examples of what can be done. Hopefully they will both make a positive difference.

left: original map of the Elterwater Gunpowder Works, with the Cylinders Farm | image © Factum Foundation

project info:

name: Merz Barn

artist: Kurt Schwitters

restoration: Factum Foundation for Digital Technology in Preservation | @factum_foundation

location: Cumbria, United Kingdom

happening now! thomas haarmann expands the curatio space at maison&objet 2026, presenting a unique showcase of collectible design.