henrique oliveira was 18 years old when he first entered an art museum. ‘my mother always fostered the natural aptitude that I had for drawing by sending me to painting classes,’ he shares in an interview with designboom. ‘however, in my childhood there was no reference to what art was and how being an artist could be a professional option. I only realised this later on — art could be a career rather than just a lifestyle.’ growing up in a small town within the state of são paulo, brazil, oliveira cultivated a strong connection with nature. oliveira’s early relationship with the natural world, coupled with an obsessive need to draw and later six years of artistic education at the university of são paulo, would go on to form the multilayered universe that his practice now spans.

from installations architectural in scale to ‘fantastic portals’ and paintings, oliveira’s work evokes a duality between the urban and the organic, nature and construction, and reality with the spectacular. ‘it interests me a lot — the idea of intervening in the fabric of the real,’ he says on his outdoor works, which have emerged from buildings in brazil and medieval walls in bruges. ‘this speaks to the relevance of sculpture in the contemporary world, to its ability to survive outside the protective aura of the museum and to establish a relationship with audiences beyond the usual visitors to spaces dedicated to art.’

banisteria caapi (desnatureza 4), 2021 | bruges triennale | plywood and metal | 5 x 6 x 1m

read more on designboom here

designboom spoke with henrique oliveira about art as a ‘free zone’ of human knowledge, social media as a factory of anxieties, and the best moment of the day.

designboom (DB): what aspects of your background and upbringing have shaped your creative principles and philosophies?

henrique oliveira (HO): I grew up in a small town within the state of são paulo, brazil. my parents were young during the 60’s and 70’s, so were directly influenced by the changing traditions and expanding freedom that characterised those years. so I grew up in an environment that was quite liberal.

my mother always fostered the natural aptitude that I had for drawing by sending me to painting classes. however, in my childhood there was no reference to what art was and how being an artist could be a professional option. I only realised this later on — art could be a career rather than just a lifestyle. at the age of 16, I moved to são paulo capital, but it was only at 18, when a friend from college took me to MASP (museum of art of são paulo) that I first entered an art museum.

back in my hometown, I had a strong connection with nature. there was not much to do there, so our entertainment was to go swimming in a river, camping, kayaking, waterfalls, etc. I had some older friends who incited my interest in meditation, yoga and spiritualism. I changed my diet to vegetarianism at that time and still keep it today. my visual references were mostly from vinyl covers, tattoos and psychedelic art. art books were a rarity to come across.

sysiphus casamate, 2019 | jardins des plantes, le havre france | plywood, tree branches, other materials | 6x6x20m

HO (continued): at first I thought about being a cartoonist. I was quite good at caricatures. but when I was 18, I went through a kind of initiation rite (at least that was how I interpreted it later on, after reading jung’s ‘the man and his symbols’). together with two friends, we took magic mushrooms. it was a terrible experience, but it was also fascinating because I reached the limit of madness. the visions stayed in my memory the following days and I felt the need to give form to that experience. drawing started to serve as a kind of repository to represent the possibility of reconstructing things that could not be adequately expressed in words. I began to draw almost obsessively.

a few years later in são paulo, I took painting classes with two artists, which not only provided me with more sophisticated plastic means, but also helped me prepare to go to art school. it was then at the university of são paulo, where I spent six years, that my knowledge and training in art really began. it was also a more urban experience within my life, when I spent more time in the city as opposed to back in the country. my collage work with used plywood started during those years as a result of my random walkings around the city.

trancorredor, 2016 | centropecci, italy | mixed media | 3 x 10 x 48m

DB: where do you work on your projects? how is your studio activated on a day to day basis?

HO: my practice is basically divided between working in my studio and traveling to create exhibitions on different sites. in the studio, I follow a routine that varies between paintings, drawings and sculptures etc.

when I travel to produce an installation, the work is more intensive because I have a deadline to fulfill, so there is less room for experimentation. on the other hand it forces me to act quickly to find solutions for many different situations — which at the end of the day has contributed a lot to the fast development of my production.

trancorredor, 2016 | centropecci, italy | mixed media | 3 x 10 x 48m

HO (continued): in the studio the atmosphere is normally a lot calmer. the ideas float in the air and I always work on different things at the same time. many unfinished works haunt the space. there is much less pressure, but more anxiety on the openness of multiple possibilities. usually I work on sculptures in the afternoon while my assistants are around, then when the evening comes, I switch to painting. ideas for projects often come up during my painting sessions, when I stop thinking about what to do and just follow the viscosity of the medium. when this happens, I stop for a few minutes and go to a sketch book.

I see the two practices — studio and site production — as complementary to each other. after a season traveling to produce a work, I return to the paintings with renewed breath. traveling to work, on the other hand, offers me a break from studio routine.

DB: what is the best moment of the day?

HO: having breakfast reading the newspapers (nowadays not the brazilian ones).

baitogogo | palais de tokyo, paris | photo © andré morin

read more on designboom here

DB: your work traces the narrative of materials from their origins in nature, to their use in construction and architecture, to their reconfiguration into natural forms — can you talk about the idea of transformation, and how your projects share the story of the materials from which they’re made?

HO: the idea of using wood to build the shape of a tree is not new. but I think in the way that I do it, subsists an ethos that mirrors the moment we as humans are going through. especially in works where this reconstruction reaches a higher degree of mimesis — here I refer to some of my recent sculptures that, at least in photos, can hardly be distinguished from a real tree. it is as if the heyday of the technique that I have developed over 15 years had overflowed the spectacular aspect of some of my earlier works, and has now moved towards a more banal state of a natural object. a turning point in my use of plywood so far. the sense of the practice seems to have shifted from the pure visuality of my early installations to another layer of meaning, hidden in the simplicity of the final work, which can be inferred by requiring a careful look from the observer. these works are certainly less generous than those I used to do ten years ago. for that very reason, they also may reveal a kind of ‘sisyphus effort’ that characterises the contemporary world, where the fruit of technological development seems to have turned from a solution into a challenge.

devir, 2017 | van de weghe, NY | plywood and tree branches | photo by ali elai camerarts

it is a laborious process for a banal result. I think that this is related, although obliquely, to our present time when the biggest human efforts start to be directed no longer to change nature, but to maintain what has always been the predominant element in the historical and prehistorical relationship of man with his natural environment.

conundrum, 2020 | plywood, barks and branches | 70 x 175 x 110cm | photo by everton ballardin

DB: many of your works have been immersive in nature — what relationship do you want them to have with the body or the person experiencing them?

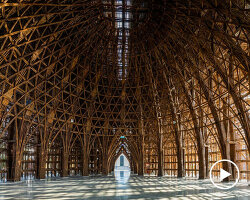

HO: many of the environmental installations made since the 50’s and 60’s were composed of multiple elements separated from each other, in such a way that the idea of an art object would tend to disintegrate so that the immersive experience would be brought to the fore plane. it was a moment of dissolution of the borders that used to separate genres of art. but when that dissolution reaches its limits, it is necessary to recompose its fundaments or it may get diluted in the world. I try to think of my immersive installations as similar to my smaller sculptures, in a way as if they were the same sculptural objects — but on a scale that they can be penetrated with the body and not just with vision. so, the experience of the senses becomes intrinsic to the object — the smell of old wood, the sounds provoked by walking (which have their origin in the way the bits of materials articulate), the instability of the pathway and the tactility of the surfaces.

I often see the term ‘monumental’ associated with these works. I understand this relationship by the fact that I produce small objects with similar materials, but I never use this adjective because I see this dimension of the body as co-extensive with the scale of use of plywood units. these works happen on the same level of architecture, caves, walls — this is their natural scale. finally, they are works that, although functioning as fantastic portals, have their foundations solidly grounded in the physical world. they happen in the same space that we inhabit.

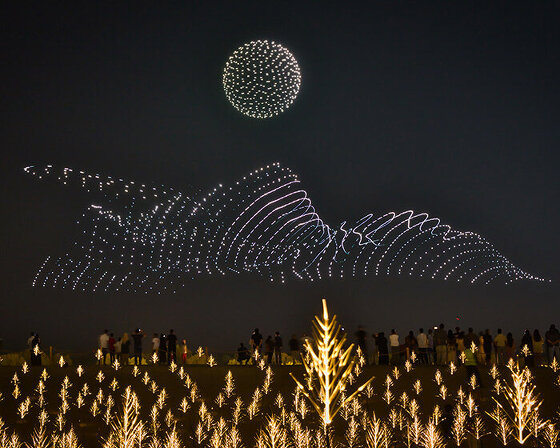

occupation, 2016 | colegio benigno malo – 13th bienal de cuenca ecuador | paper mache and wire mesh

DB: what are the differences between working in outdoor or urban contexts compared with an indoor gallery or exhibition space? do you have a preference?

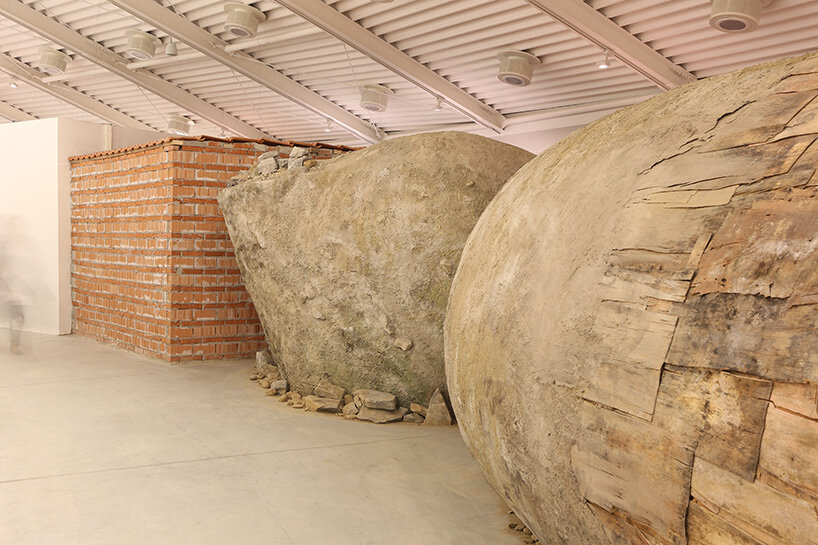

HO: within the clean environment of galleries and museums, the work tends to function as a contrast. if it on one hand enhances their visual impact, it also tends to give them a theatrical atmosphere. white cube spaces are environments that function as a kind of parenthesis in the world — as if their function was to say: from here life ends and art begins.

when the work is out of this environment, whether in nature or in the city, the viewer can be caught off guard. a dubious situation may emerge, as people tend to question the purpose or the nature of this. it interests me a lot, the idea of intervening in the fabric of the real. this speaks to the relevance of sculpture in the contemporary world, to its ability to survive outside the protective aura of the museum and to establish a relationship with audiences beyond the usual visitors to spaces dedicated to art.

I rarely used to be invited to create external works, but this has changed and I am enjoying it.

xilempasto11, 2016-18 | plywood and pigments | 270 x 290 x 76cm | photo by everton ballardin

DB: how planned is the outcome of each piece in advance? in general, does spontaneity and improvisation hinder or help express your vision?

HO: it depends a lot on the type of work I’m going to do. at the studio everything happens in a more free and experimental way, I rarely produce models. when it comes to a commissioned project, I prepare some drawings beforehand — often just to please whoever is ordering the work. but I always make it clear that the final design will only be established in the physical space. in the end, the projects serve more to define the starting point and the general concept of the work. although most invitations are accompanied by project requests, I like to think of art as a kind of free zone of human knowledge. an area of action that is free of pre-established limitations.

parietal passage, 2016 | martaherfortmuseum germany | plywwod, bark, moss, PVC

HO: certainly society is increasingly turning more and more into a virtual world. especially amongst the younger generations, it is difficult to find someone who does not spend the day with their nose sunk into their smartphone. the result seems to be something like a fractional reality. if my generation had a hard time concentrating for more than 20 minutes because it was conditioned by the timing of TV commercials, the world of social media is a factory of anxieties. the physical dimension has been pushed to a background plan, a framework from where everything emerges from and refers to, but paradoxically can never be fulfilled in its plenitude because communication became completely detached from that plan.

transarquitetônica | MAC USP, são paulo, brazil | photo by everton ballardin

read more on designboom here

HO (continued): but thinking optimistically, in the end — all these anxieties have to go down to drink water from the valley of physical reality. perhaps this explains the crowded parks on weekends, the jammed roads that go down to the beaches, the waiting lists in the restaurants and the queues at museums doors. I think that to the same extent virtual images become ubiquitous in people’s lives, the search for material compensation in the physical world also grows, and it happens in the art context too.

transarquitetônica | MAC USP, são paulo, brazil | photo by everton ballardin

transarquitetônica | MAC USP, são paulo, brazil | photo by everton ballardin

read more on designboom here

DB: what are you currently fascinated by, and how is it feeding into your artistic practice?

HO: I’ve been living in london since last year. in the last few months, I have been working on projects in europe. between these trips and the quarantines, when there is some time left, I’ve been slowly setting up my studio.

when the pandemic broke out, I was in brazil and couldn’t make it to london. I worked a lot in my são paulo studio, which remains active. it was a good time to read and produce without pressure. of all that I read during this period, a book that struck me was ‘the neanderthal’s necklace’ by juan luis arsuaga. I was fascinated by the descriptions of paleo-anthropological sites in northern spain, wondering how the homo sapiens, which at some point almost disappeared from the planet, became what we are today. the landscapes and the shape of the rocks, the role of nature perception in the process of the development of our language, the first artefacts produced. I was working on such themes before I left for london. several works are on their way and shall be part of my next exhibition in são paulo next year.

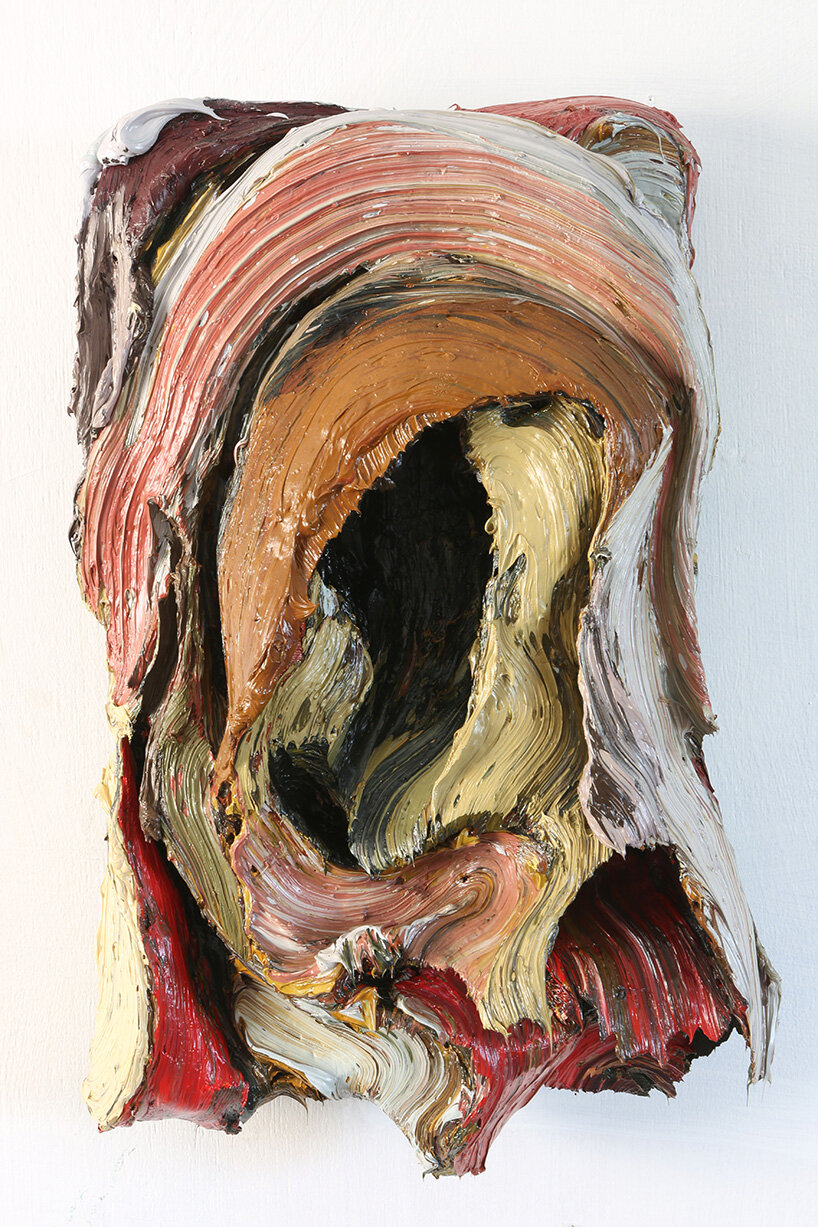

EXLP26, 2019 | oil on paper mache and wire mesh | 50 x 32 x 16

DB: can you tell us about any other upcoming projects you are particularly excited about?

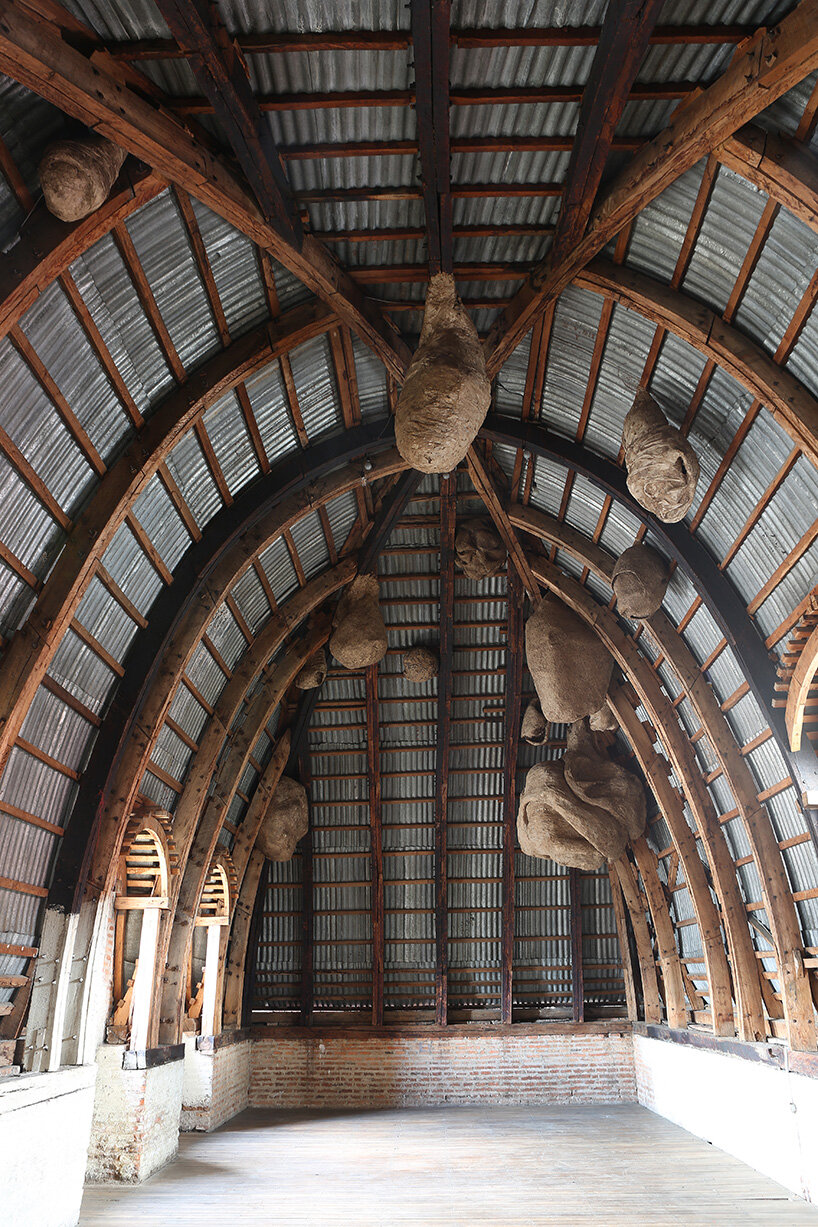

HO: next weekend I’m going to holland to produce a work for ijssel biennale. it is a new event that proposes works in the landscape along the ijssel river valley. the curators offered me the ruins of a mill, which I found quite picturesque for a new sculpture-installation. it is the type of project where I feel free to experiment and improvise, as it does not have strong pressures or expectations. so I drew some cuts of flexible plywood and sent them to prepare the material accordingly. then I asked them to bury it all and leave it maturing for three months.

I also just finished producing a work for the bruges triennale, in belgium. the show just opened. it is a structure that resembles vines and was built on a medieval wall that dates from around the 11th century and is located in an external area on the banks of a canal.

last week, I was with my assistant in denmark. I collaborated with the new museum dedicated to the writer hans christian andersen. they asked me if i could do one my tree-sculptures. I made one that grows from a concrete column, a bit like the magritte shoes that turn into feet.

desnatureza 3, 2018 | villa aymoré, rio de janeiro, brazil | plywood and other materials | 7.6 x 9 x 6m

desnatureza 3, 2018 | villa aymoré, rio de janeiro, brazil | plywood and other materials | 7.6 x 9 x 6m

common root, 2019 | arte sella, italy | oak trees, plywood and tree bark among other materials | 4.5 x 33 x 10m

happening now! thomas haarmann expands the curatio space at maison&objet 2026, presenting a unique showcase of collectible design.