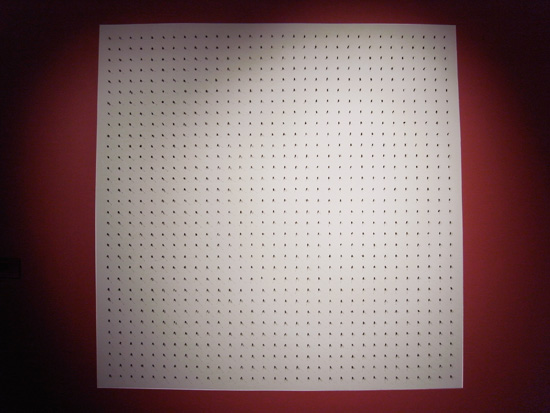

needle in my consciousness, 2003 private collection image © designboom

‘after president suharto’s regime fell, a culture of violence bared its claws upon our society. an indifference to the people’s fate on one hand and narrow-minded partisanship on the other made me feel sickened by the situation. this nausea and pessimism gave me a strong push to leave social themes behind. I felt I had lost my orientation on morals, ethics and even nationalism. if they were all still being voiced, I felt them as empty slogans with no meaning at all. in the time that followed, I felt that I had lost my footing and felt alienated among my own community. this was the community that I had once considered as the marginalised.

people I had to fight for through my art. I then felt alienated from the people I had considered to have a similar vision for change. the nakedness and simple-mindedness revealed through their actions, brought me to the point of asking, ‘who are they, really?’ in a change like this, I try to see myself over again…’ fx harsono, 2003

detail of needle in my consciousness image © designboom

detail of needle in my consciousness image © designboom

marking harsono’s first exploration of the needle as a metaphor for the expression of unspoken pains, needle in my consciousness was made in response to the bombing of jakarta’s jw marriott hotel. the needle of pain, in this case, is the ever-present, nebulous threat posed to the individual by violent currents within society; the niggling, uneasy sense that one is never truly safe, that at any moment forces beyond an individual’s control may strike one down, in physical and other senses. for harsono, this applies not only to the rise of violent fundamentalism, but other, less visible forms of prejudice which pervade society. one such example, drawn from harsono’s personal experience, would be the discrimination against the chinese in indonesia, which was a matter of state policy during the new order.

the work itself presents a tableau of harsono in a number of attitudes, each overlaid with one or more needles, as if piercing him: the repose of death, meditative concentration, the sleeping buddha. each panel presents him in relation to fields of mostly pure colour, allowing us to focus on the elements in play – himself, the needle and the tale of the needle which carries over from the world of dreams to the waking world.

detail of needle in my consciousness image © designboom

detail of needle in my consciousness image © designboom

bon appetit, 2008 – installation with needles and butterflies on a table with tableware artist collection image © designboom

bon appetit, 2008 – installation with needles and butterflies on a table with tableware artist collection image © designboom

in this installation, a table is laid for a meal, the cutlery and chinaware meticulously arranged according to the table etiquette of the elite, anticipating the arrival of diners possessing social status and privilege. startlingly, the bowls and plates are filled not with food but with butterflies, neatly fastened to the chinaware. much of harsono’s recent work has employed the butterfly as a symbol of a victim – beautiful and vulnerable, and inevitably, destined for destruction or attack. the butterflies in bon appetit are forcibly pinned down, about to be consumed. while the work appears charming on the surface, it nonetheless hints at unequal power relations in society, and the relationship between the powerful and the powerless. the suggestion of a domestic or interior setting also marks a shift from harsono’s earlier works, where the streets and public areas were the theatres of violence, and sites of protest and resistance. now, as bon appetit suggests, violence and danger have subtly infiltrated the home, the most personal and private of spaces.

close-up image © designboom

close-up image © designboom

bon appetit image © designboom

bon appetit image © designboom

bon appetit image © designboom

bon appetit image © designboom

view to the exhibition image © designboom

view to the exhibition image © designboom

kuteropong (watching the wound), 2007 private collection image © designboom

kuteropong (watching the wound), 2007 private collection image © designboom

from behind his hands, cupped to resemble a pair of binoculars, harsono surveys what lies beyond – the viewer, or perhaps, the butterfly pierced by a needle and set aflame. the imagery in this diptych conflates a number of motifs employed by the artist in his work of the 2000s: the needle, as an insidious threat and metaphor for pain; the butterfly, as victim; fire, as a metaphor for violence and destruction; and finally, the erasure of the subject or self, to reflect uncertainty about identity and shifting positions. this work is harsono’s introspection of his efforts as an artist, who was mostly preoccupied with social issues. made when he was intensely questioning his self-identity, attempting to reassure himself that within the ‘personal’ there remains a social dimension, the artist nonetheless continues to harbour doubts, questioning how close or how far the personal is from the social or the political. harsono thus began to gauge the issue through reading books, seeking relevant references to ascertain the proximity and distance between these two seemingly paradoxical fields. right before his face, a dead butterfly pierced by a large needle emerges, a metaphor emphasising the fragility of the victim, the very subject that has delivered him to the domain of self-identity and its contexts of power. is speaking of the victim a personal or social subject? the difficulty in answering this question is hinted at by the doubled image of the diptych, which brings to mind the technique of stereography, in which viewing two images at slightly different angles generates the illusion of depth.

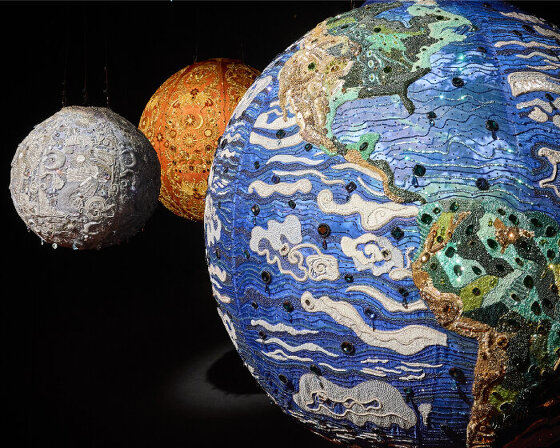

thousand times pain, 2007 – installation with bees and needles artist collection image © designboom

thousand times pain, 2007 – installation with bees and needles artist collection image © designboom

a recurrent motif in harsono’s recent body of works is that of the needle, which the artist likens to a tiny ‘point’ of pain. while the pain caused by the fine point of a needle is slight, subtle when compared to the brutality and forceful violence suggested by the charred and dismembered human figures of earlier works, the pain is, nonetheless, palpable. repeated, these ‘points of pain’ accumulate to slowly wear down their victims by a gradual process of attrition. this is conveyed through the installation thousand times pain, where a thousand bees are pinned to the wall with needles. individually, they appear insignificant; their pain passes us by, insidious in its subtlety. amassed into a grid, where the subtle violence is repeated a thousand times over, they convey the haplessness of victims in a potent symphony of subtle agony.

thousand times pain image © designboom

thousand times pain image © designboom

open your mouth, 2002 artist collection image © designboom

open your mouth, 2002 artist collection image © designboom

the reformasi period in indonesia saw the gradual expansion of civil liberties, such as the freedom of speech and dissent, a relaxation of censorship and the reclamation of public spaces. the imagery of open your mouth can be understood in the light of these new developments, presenting us with an ambiguous metaphor for a newly liberalised society. it could well be that the hands forcing open the mouth of the person in the print are a symbol of this new openness, or that the hands belong to the man himself. either way, the man depicted is – or feels – compelled to say something; after all, indonesians had been denied the right to free speech for so long under new order – yet nothing comes out. what is there left to say that still makes sense, or which is meaningful? what does the freedom of speech amount to, if all which results are sound and fury, signifying nothing? the blank spaces in his eyes, nostrils and gaping mouth suggest that his soul, or inner being, has vacated, and all that is left is an empty, hollow shell, reflecting the hollow victory of finally being able to express oneself now.

close-up of open your mouth image © designboom

close-up of open your mouth image © designboom

image © designboom

image © designboom

preserving life, terminating life #1, 2009 artist collection image © designboom

preserving life, terminating life #1, 2009 artist collection image © designboom

the images in these two canvases are drawn from the same source – old albums of black and white photographs that harsono discovered in his family home, and which subsequently inspired his most recent body of work, which investigates personal – as well as political – history. in these two paintings, images of harsono’s family members are juxtaposed with images documenting the exhumation of the mass graves of chinese murdered in the turbulent years after the second world war. this juxtaposition poignantly highlights the preciousness and precariousness of life – the lives of those members of the chinese community and harsono’s family who were lucky to escape the violence, and the lives of generations to come, as intimated by the marriage portrait of the couple in the first painting, and the family portrait in the second painting, where the visibly pregnant mother reclines in the background, and the father hovers protectively over his firstborn in the foreground. binding these two disparate halves – family life and cause for celebration on the one hand, murder and death on the other – is a string of words echoing the titles of the works, stitched into the canvases with red thread. for the chinese, red thread is associated with occasions both auspicious and inauspicious. at weddings and other celebrations, red clothing is worn as a celebratory gesture; at funerals, pieces of red thread are given to guests to bring home when they leave the place of mourning, as a symbol of blessing to ward against unhappy spirits. it is therefore apt that harsono has chosen to bind the two halves of his canvases with a line of words stitched with red thread – the visual motif of the red line simultaneously suggesting lineage and blood ties, as well as the continuous line of history, all too often stained by bloodshed and violence.

detail of preserving life, terminating life #1 image © designboom

detail of preserving life, terminating life #1 image © designboom

rewriting the erased, 2009 artist collection image © designboom‘rewriting the erased’ is my work to show that I try to remember my chinese name. for about more than 40 years I never used that name again.’ fx harsono.

rewriting the erased, 2009 artist collection image © designboom‘rewriting the erased’ is my work to show that I try to remember my chinese name. for about more than 40 years I never used that name again.’ fx harsono.

image © designboom

image © designboom

in a darkened room, fx harsono sits at a table with paper, ink, and a brush. slowly he begins to write his name in chinese, character by character. he repeats this, placing each sheet of paper with the three chinese characters on the floor, and starts to write on the next sheet, until the entire floor is papered over with his name. in this poignant and meditative performance, the artist seeks to remember – reclaim – that which has been lost or erased. being of chinese descent in indonesia meant that harsono, like many others, was cut off from his chinese ‘roots’ and culture through a series of government policies aimed at fully assimilating chinese immigrants into indonesian society. these measures, implemented during suharto’s new order regime, included requiring all chinese to change their names to indonesian-sounding ones, as well as the closure of chinese schools, press and organisations.

the end of suharto’s new order in 1998 witnessed a lifting of these restrictions, and the chinese were once again able to use their original names. during this time, harsono began to question the seemingly conflicting facets of his identity: indonesian, chinese and catholic. for most of his life, he had to practise a ‘politics of denial’ in order to feel that he belonged somewhere, and this meant the suppression of his ‘chinese’ identity. now that he is free to reconnect with this forgotten, or repressed, aspect of himself, he seems to question, through this work, if that past still holds any significance for him, or is it, when revisited, simply a series of empty and meaningless gestures, taking shape as ideographs from a language and culture that harsono can only half-understand? the gestures of the artist are filled with both pathos and power, as he attempts to reclaim a past that is at once intensely personal as it is politically inflected.

rewriting the erased – video performance of the artist image © designboom

rewriting the erased – video performance of the artist image © designboom

nDudah, 2009 – documentary image © designboom

nDudah, 2009 – documentary image © designboom

ndudah is javanese slang that means ‘once again taking something apart, or digging something up’. harsono heard this word spoken by the villagers around the town of blitar, where he was born, during a survey he conducted in august 2009. the villagers he met still remember digging up the victims – mostly ethnic chinese – of a massacre that has not been (and may never be) included in the official history of indonesia. harsono’s survey concerned the massacre of ethnic chinese that had occurred in blitar and its environs from 1947 to 1948, when the dutch attempted to retake the newly independent nation by force. to defend against these incursions, the republic’s administration attempted to employ a ‘scorched earth’ strategy, leaving barren and empty those cities which the dutch would attempt to occupy. in the chaos resulting from forced evacuation, there were a number of killings and robberies of the ethnic chinese, which may have been exacerbated by the military’s conscription of the inmates of kalisosok penitentiary, who were given weapons and instructions to empty the city. harsono’s investigations began with a series of black and white photographs taken by his photographer-father in 1951, when the latter worked with the chinese organisation chung hua tsung hui in an attempt to recognise the victims, trace their origins and family, and then give their remains a proper burial in one place, now named ‘bong belung’, (‘bone grave’). the number of victims found was 191. the ndudah video documentary project was conducted by harsono by interviewing still-living eye-witnesses, the families of the victims, and survivors of the massacre. he also consulted a book which chronicled the history of the massacre, titled ‘tionghoa dalam pusaran politik: mengungkap fakta sejarah tersembunyi orang tionghoa di indonesia’ (‘the chinese in the political vortex: disclosing the hidden facts of history about the chinese in indonesia’). he then arranged the outcome of the interviews, testimonies and his father’s photographs into a documentary video. ndudah is hence a significant work that chronicles and bears witness to an unspoken chapter of indonesian history, and the problems of the position of the chinese diaspora in indonesia that persist till today.

see also fx harsono: testimonies – part 01

happening now! in an exclusive interview with designbooom, CMP design studio reveals the backstory of woven chair griante — a collection that celebrates twenty years of Pedrali’s establishment of its wooden division.