exhibition entrance

fx harsono: testimonies SAM – singapore art museum march 4th – may 9th, 2010

the exhibition presents a survey of artworks by indonesian contemporary artist fx harsono: from the artist’s earlier conceptual works during the gerakan seni rupa baru movement (new art movement) of the 1970s; to political works and installations of the 1990s that critique the regime of power and oppression in indonesia; until recent, more personal investigations into issues of self-identity and family histories.

through these various ‘testimonies’, the exhibition offers a glimpse of the political, social and cultural changes that have shaped indonesian society. with a belief in the potential of art to address injustices in society, harsono shows the horrors of social injustice and discrimination in his country. it shows the artist’s constant re-evaluation and re-positioning of his role throughout this recent history.

‘social and cultural issues cannot be detached from the creation of art work: creativity in art must be able to reflect social issues, as well as raise the audiences’ awareness… at this point, my art is a form of expression trying to remind the audience of the problems we are facing together…’ fx harsono (1994)

paling top ’75, 1975 – plastic gun in wooden crate artist collection image © designboom

paling top ’75, 1975 – plastic gun in wooden crate artist collection image © designboom

artists from the gerakan seni rupa baru (new art movement), such as fx harsono, jim supangkat, nanik mirna and art critic sanento yuliman called for new approaches to the theory and practice of art. using objects familiar to everyday life was a way to create works that related to local experiences.

in paling top ‘75, fx harsono rejected the notion of the ‘artist’s hand’ – visible traces such as brushstrokes in a painting – as one of the elements which give an artwork its significance or aura. as an alternative, he appropriated commonplace objects, such as a toy gun and a wooden crate, which he paid a carpenter to fabricate. the use of ready-made and everyday objects to make artworks challenged the institutions of art education such as the bandung institute of technology (ITB) and the indonesian arts academy (ASRI) in yogyakarta, which defined fine art as painting and sculpture personally executed by the artist in accepted media, such as oil paint. rejecting the need for artists to actually make their works also went against principles espoused by modern artists like s. sudjojono, who advocated the idea of jiwa ketok – the artist’s ‘soul made visible’ on the canvas.

paling top ’75 also confronts social and political reality head-on. the toy gun encased in a wooden crate with wire mesh symbolises the power of the military in all facets of life in indonesia, and the subjugation of the indonesian people to this power. under suharto’s new order regime, where art was deliberately de-politicized, such critical political commentary in art was a risky endeavour and made patently clear a belief that art needs to actively engage with society and its politics.

voice without voice / sign, 1993 fukuoka asian art museum collection image © designboom

voice without voice / sign, 1993 fukuoka asian art museum collection image © designboom

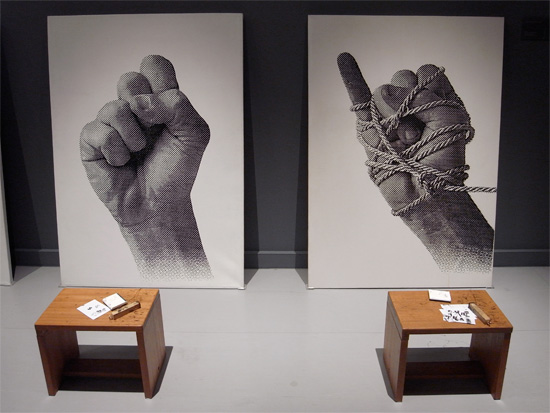

voice without voice / sign comprises a row of panels, each imprinted with a gesturing hand. collectively the various gestures spell out, in universal sign language, the letters d-e-m-o-k-r-a-s-i. the row of gesturing hands, and in particular the clenched fists that form the letters ‘e’, ‘a’ and ‘s’ bring to mind the actions that accompany public protests, which, together with the dramatic chiaroscuro, lend this work much of its forcefulness and urgency. however, sign language is the recourse of the mute, and this work implies that the ‘voice’ of the people has been silenced. these demonstrations for democracy are also futile; they exist only as gestures frozen on canvas panels, abstracted from the potent immediacy of actual action. to make this painfully clear, the last hand which forms the letter ‘i’ is bound with rope. while the work spells out uncompromisingly the demand for democracy, it is also a sign of the impossibility or futility of political action. demokrasi (democracy) exists only as a series of empty gestures; it is represented purely as a sign, an abstraction, rather than concrete reality.

voice without voice / sign – silk screen on canvas (9 panels), wooden stools and stamps image © designboom

voice without voice / sign – silk screen on canvas (9 panels), wooden stools and stamps image © designboom

wooden stool and stamps image © designboom

wooden stool and stamps image © designboom

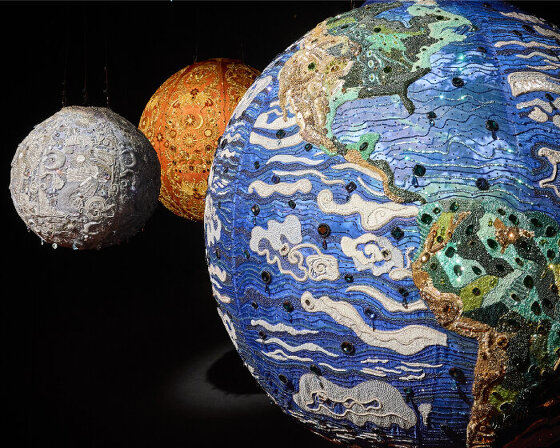

image © designboom

image © designboom

‘destruction’ video performance, 1997

‘destruction’ video performance, 1997

destruction was harsono’s contribution to slot in the box, an exhibition organised by the cemeti gallery. slot in the box called together artists from across indonesia to engage with the new order’s electoral fraud through such diverse forms as installation and performance art; other entries included yustoni’s open your freezer and find new clothes for the president, which critiqued the foregone conclusion of the presidential elections, and weye haryanto’s lip-service democracy, which responded to suharto’s lip-service to democratic ideals in consistently engineering the victory of his golkar party (golongan karya).

destruction was performed during the so-called ‘silent week’, a period prior to elections during which public assembly of more than five people was declared illegal; as such, harsono’s performance placed him at personal risk of arrest. this performance saw harsono assuming the role of the uncontrollably powerful demon king ravana, prime antagonist of the epic sanskrit poem the ramayana. dressed in a business suit, harsono set fire to three wayang masks on chairs, which represented the only three political parties suharto allowed to contest the elections: his own golkar party, the islamist united development party (PPP), and the democratic party of indonesia (PDI). using a chainsaw too powerful for its task, harsono destroyed the burnt chairs, as a metaphor for suharto’s brutal exercise of power over the electoral process. the mangled remains of the chairs and masks serve as an installation alongside a video of the performance; reminders that power should always be kept in check.

exhibition view image © designboom

exhibition view image © designboom

burned victims (front), 1998 artist collection image © designboom

burned victims (front), 1998 artist collection image © designboom

conceptualised as a performance-installation, the performance component of burned victims involved the burning of five wooden torsos, during which a placard was displayed to the audience, bearing the word kerusuhan, or ‘riot’. in the work’s installation component, the blackened remains of the wooden torsos are suspended in oblong metal frames, arrangements of regular lines which highlight the agonised contortions of the torsos. placed before each torso is a pair of burnt footwear, rendering the figures all the more forlorn. this performance-installation was made in response to a tragic episode of the may 1998 riots, during which the rioting mob stormed a shopping mall, sealed off its exits and set it on fire. the motives for such callous brutality remain unknown. whatever the reasons, the hundreds of people who were trapped and burnt to death in the shopping mall were all victims of a power struggle that culminated in the downfall of suharto. in an almost photo-journalistic fashion, the artist presents to his audience the scorching image of the victims’ bodies, to elicit horror and condemnation of civil violence.

burned victims image © designboom

burned victims image © designboom

close-up image © designboom

close-up image © designboom

burned victims image © designboom

burned victims image © designboom

video of the installation ‘burned victims’ image © designboom

video of the installation ‘burned victims’ image © designboom

rantai yang santai (the relaxed chain), 1975 – installation with cushions and chains artist collection image © designboom

rantai yang santai (the relaxed chain), 1975 – installation with cushions and chains artist collection image © designboom

the new order (1965 – 1998) established by president suharto de-politicized art in indonesia by oppressing through various means those artists deemed to have aligned themselves with political organisations such as the people’s cultural organisation (LEKRA), which was influenced by the indonesian communist party. artists who produced works that were perceived as being political or critical of the new order faced similar consequences. this climate of fear was not restricted to artists, as all opponents to the authoritarian regime were brutally suppressed.

rantai yang santai makes visible the oppressive climate that prevailed during the new order years. for fx harsono, it was a powerful statement on how the military’s presence was so pervasive in all facets of indonesian life, that it even haunted one’s dreams and moments of repose. at the same time, as the english translation of the artwork title suggests, the juxtaposition of the cushion (symbolising relaxation) and the chain (a metaphor for imprisonment) begs the question: have we become so accustomed to the suppression of free speech and expression that we find oppression and injustice comforting and familiar?

republik indochaos, 1998 SAM collection image © designboom

republik indochaos, 1998 SAM collection image © designboom

an ironic inversion of the commemorative function of postage stamps, republik indochaos is the result of harsono the individual electing to immortalise scenes of violence and death, as opposed to a state inscribing the memory of its own glory. a portrait of suharto with the bahasa indonesia word lengser or ‘stepping down’ branded upon his face confirms the status of the work as an incisive critique of the violence and destruction of the 1998 riots in indonesia, which had as its root the failure of the political establishment. images of soldiers taking aim at protestors, and buildings and motorcycles burning, confront us with the chaos brought upon by the inability of the government to establish control and maintain security. an image of security personnel beating demonstrators with batons is accompanied by the following caption: kekerasan tidak menyelesaikan masalah (violence is not a solution). rather than glorifying national achievements through stamps, harsono has literally enshrined the memories of the people who lived through the 1998 riots and experienced the traumatic events first-hand. republik indochaos is a stark reminder never to forget; more importantly, never to repeat the uncontrolled escalation of violence that led to so many deaths.

republik indochaos image © designboom

republik indochaos image © designboom

close-up of republik indochaos image © designboom

close-up of republik indochaos image © designboom

the voices controlled by the powers, 1994 artist collection image © designboom

the voices controlled by the powers, 1994 artist collection image © designboom

in this installation, wooden masks gaze voicelessly at a macabre centre piece: their own severed mouths, naked evidence of their violent mutilation. these traditional wayang masks, or topeng, stand as a mournful testament to the situation of powerlessness; they symbolise each and every person who has been left voiceless without recourse – a situation familiar to those indonesians who lived under the new order. the voices controlled by the powers exemplifies fx harsono’s belief that art should make visible social problems in order to effect social change, and was made in response to the forced closure of tempo magazine in 1994 for publishing an article exposing the corruption of the new order. in addition to contemporary political commentary, the work also laments the loss of traditional cultures of minority ethnic groups such as the chinese, who were not allowed to practice their own culture: alongside other discriminatory laws, chinese schools were banned and indonesian chinese were made to change their chinese names to more indonesian – sounding ones. the severed traditional masks are metaphors for the forced erasure of the diverse cultural practices of different ethnic groups in indonesia in the construction of a javanese-based national culture.

close-up of the voices controlled by the powers image © designboom

close-up of the voices controlled by the powers image © designboom

close-up of the voices controlled by the powers image © designboom

close-up of the voices controlled by the powers image © designboom

image © designboom

image © designboom

power and the oppressed, 1992 artist collection image © designboom

power and the oppressed, 1992 artist collection image © designboom

the chair, whether realised in the material form of a throne, or in the linguistic form, such as in the term ‘chairman’, can be seen as a symbol of power and authority. in power and the oppressed, a lone chair denotes authoritarian power, its lofty isolation highlighted by a coil of barbed wire. the keris pinned on the wall behind the chair allude to the privileging of javanese culture as indonesia’s national culture while suppressing other cultures during suharto’s regime. symbolic of blood, red-stained pieces of cloth are placed on piles of blackened earth arranged systematically in a grid pattern, in supplication to the chair’s occupant.

the grid-like order brings to mind the central government’s obsession with order, in its bureaucratization of all political and societal organisations. the blood also reminds us of the violent repression of political opponents, particularly the anti-communist purge in 1966 that resulted in the deaths of an estimated half a million indonesians.

close-up of power and the oppressed image © designboom

close-up of power and the oppressed image © designboom

detail of the installation power and the oppressed image © designboom

detail of the installation power and the oppressed image © designboom

detail of the installation power and the oppressed image © designboom

detail of the installation power and the oppressed image © designboom

included in the exhibition are seminal works drawn from the singapore art museum’s permanent collection, as well as from other art institutions and private collections, such as paling top (1975) and voice without a voice (1994).

about the artist born in 1949 in biltar (east java), indonesia, fx harsono is known for playing a pivotal role in the development of indonesia’s contemporary art scene. harsono’s work often shows his sense of urgency and revolutionary fervour. it offers a social critique and commentary of the political landscape of his country.

‘… at SAM, we want to not only promote emerging artists but also acknowledge and pay tribute to artistic figures in mid-career who have contributed to the region’s contemporary arts scene. a solo exhibition of harsono’s work was the perfect platform for us to do this and leads the way for three other solo exhibitions which sam will be holding this year.’ tan boon hui, director of SAM.

any discussion of the history of contemporary art in indonesia would be incomplete without an examination of fx harsono’s art and practice. harsono’s works are remarkable in that they span four decades in indonesian art and history, and have borne witness to a multitude of changes and upheavals in indonesian politics, society, and culture. throughout this time, harsono has continued to question his role as an artist and his position in society, constantly pushing his art and practice to reflect and engage with new social and cultural contexts. the indonesian art world first encountered fx harsono as a restless young artist in the 1970s.

gerakan seni rupa baru one of the founding members of the gerakan seni rupa baru (GSRB) or new art movement in 1975, harsono – together with his GSRB compatriots – was already experimenting with new modes of art-making which incorporated found objects and conceptual approaches. by the 1990s, he had established himself as a force in indonesian contemporary art, creating powerful installations with strident social commentary. these compelling works gained critical attention and were widely exhibited abroad.

the closing years of the 1990s were marked by a series of societal shockwaves which reverberated throughout the nation, in particular, the economic meltdown of the 1997 asian financial crisis generated a groundswell of public anger. in 1998, this culminated in days of brutal street violence and the fall of indonesian president suharto’s new order. indonesian-chinese artists like harsono experienced a profound sense of disillusionment, as the events of may 1998 revealed that the very ‘people’ he had fought for through his art were just as capable of brutality as the political regime, and worse – these people would turn on each other. with the veneer of control under suharto’s ‘strongman’ regime removed, the fractures in indonesian society revealed themselves more painfully than ever, particularly along ethnic lines. it was then that harsono’s art began to look inwards, as he intensively scrutinised his identity and place in society.

to date, harsono has continued to raise troubling questions about the position of minorities and the disenfranchised in indonesia. his most recent body of work draws on his family history, in an investigative journey that reveals the intersection of the personal with the political. driven by his belief that an artist needs to constantly engage with society and its issues, harsono has consistently navigated the shifting currents of indonesia’s socio-political realities, deftly re-aligning his practice to most effectively address urgent issues in indonesian society and culture. as such, harsono is widely respected by the indonesian art community. his pioneering efforts in the early days of contemporary art’s development have paved the way for a new generation of artists who look up to him as an icon.

besides his art practice, harsono also lectures on art and design, and writes regularly about social issues and the development of contemporary art. he continues to nurture and challenge the next generation of artists, and contributes to art discourse and debate in indonesia.

see also fx harsono: testimonies – part 02

happening now! in an exclusive interview with designbooom, CMP design studio reveals the backstory of woven chair griante — a collection that celebrates twenty years of Pedrali’s establishment of its wooden division.