Introducing ‘Edges of Ailey’ at the Whitney Museum

The Whitney Museum of American Art is celebrating the legacy of Alvin Ailey with the exhibition Edges of Ailey, curated by Adrienne Edwards. As the first large-scale museum exhibition dedicated to Ailey’s life and contributions, it explores into the visionary choreographer’s multidisciplinary impact across dance, visual art, and music. The focus spans Ailey’s life and creative influences, using rare archival materials, live performances, and a multi-screen video installation to offer an expansive look at his world.

In addition to visual art by over eighty artists, visitors can experience performances by Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, which will be in residence at the museum throughout the show. Edges of Ailey will be on view from September 25th, 2024 until February 9th, 2025 — designboom interviewed curator Adrienne Edwards to learn about the work and influences of artist Alvin Ailey.

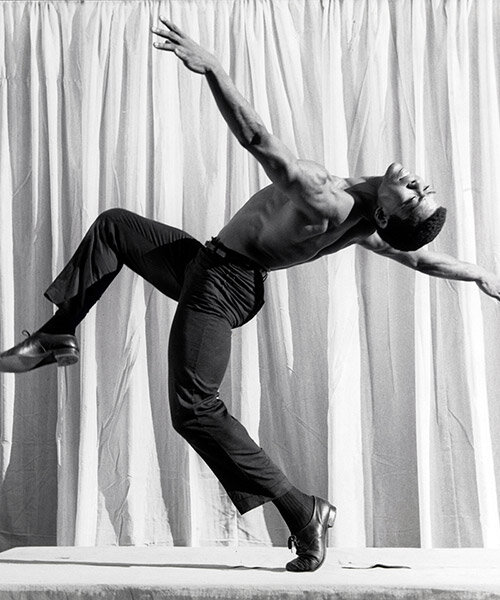

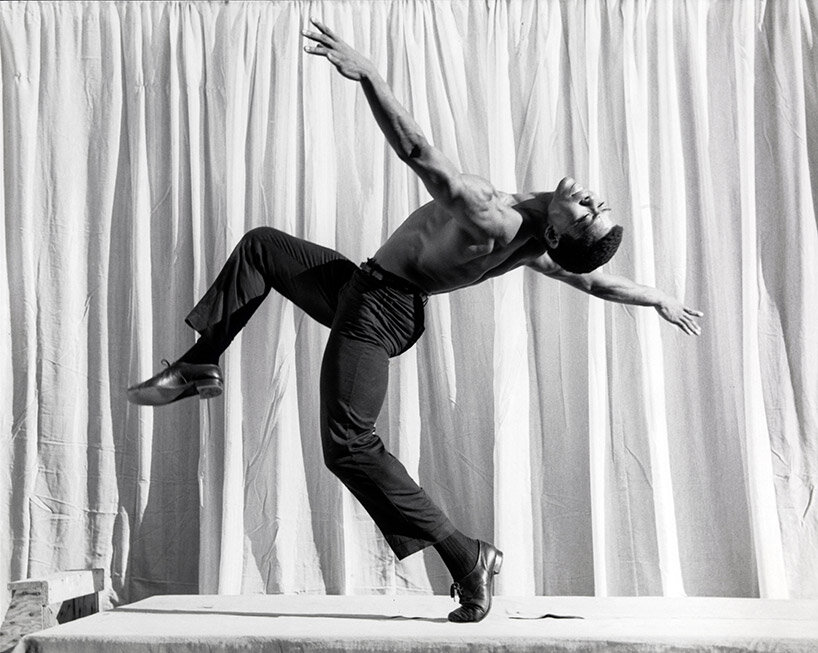

Normand Maxon, Alvin Ailey, c. 1950-1960. Courtesy the Jerome Robbins Dance Division, The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts

Alvin Ailey’s Multidisciplinary Legacy and Influence

In the following interview with designboom, curator Adrienne Edwards reflects on her personal connection to Ailey’s legacy and how the idea for Edges of Ailey originated. Edwards, a former dancer, shares how her lifelong admiration for Ailey’s work shaped the exhibition’s vision, describing it as an exploration not only of his choreography but also of his broader artistic passions, including literature and visual art. Edwards also highlights Ailey’s deep engagement with Black American culture, spirituality, and the African diaspora, underscoring the exhibition’s thematic structure, which links Ailey’s choreography to a range of artistic traditions.

Through the exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art, Edwards hopes to broaden the public’s understanding of Ailey’s artistic vision and the profound cultural narratives embedded in his work. The range of materials on display at the iconic New York museum — spanning personal letters, choreographic notes, and collaborations with prominent Black artists — demonstrates how Ailey’s influence extended beyond dance to intersect with the visual and conceptual arts. Take a closer look into the creation of Edges of Ailey, an ambitious celebration of an artist whose legacy continues to resonate across multiple disciplines.

Jack Mitchell, Alvin Ailey, Myrna White, James Truitte, Ella Thompson, Minnie Marshall, and Don Martin in “Revelations”, 1961. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture and Alvin Ailey Dance Foundation, Inc. © Alvin Ailey Dance Foundation, Inc. and Smithsonian Institution

in conversation with curator adrienne edwards

designboom (DB): What inspired the Whitney Museum to curate an exhibition focused on Alvin Ailey’s life and legacy? How did the idea for Edges of Ailey originate?

Adrienne Edwards (AE): It’s coming from a lot of different places. I’m a former dancer. I danced as a kid and throughout my teenage years, and one of my first art experiences was an Ailey concert. In some ways, I’ve been thinking about Ailey my whole life. It came about when I was having lunch with Scott Rothkopf, who was then the Chief Curator at the Whitney and is now our Director. He said to me, ‘What show do you think needs to be done that hasn’t been done?’ I didn’t miss a beat, and I said Ailey.

It was mostly because I was really surprised that no one had done it around this time period. There were a lot of exhibitions being made about dancers, and they were sort of falling into two camps. One camp was ballet — with dancers like Balanchine — and the other is the Judson Dance Theater which couldn’t be more opposite of that. Artists affiliated with that are Merce Cunningham, Tricia Brown, Yvonne Rainer, and Simone Forti. But never anything about Ailey. I thought that there must not be enough to work with, because clearly someone would have done this show — but there was plenty to work with!

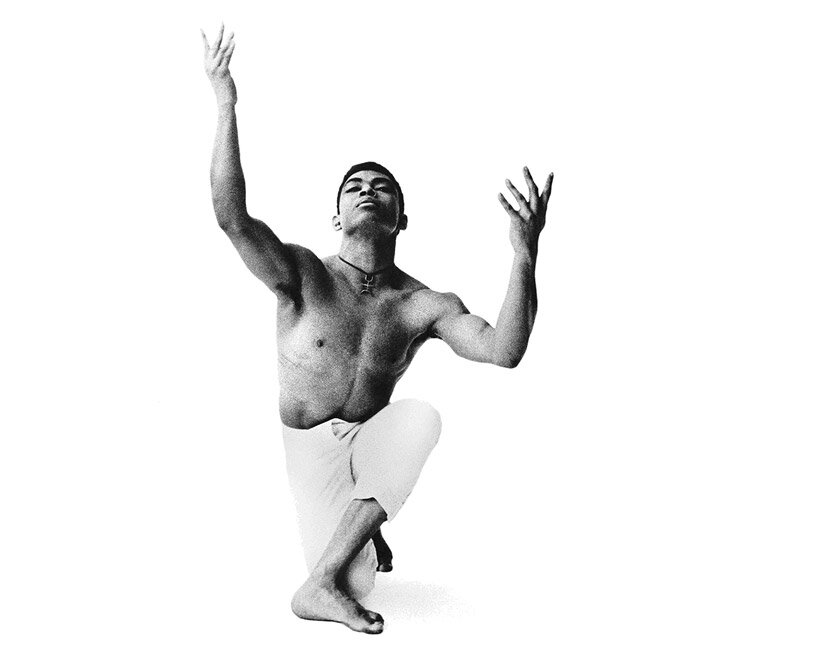

Alvin Ailey. Photo by John Lindquist. © Harvard Theatre Collection, Houghton Library, Harvard University

DB: Ailey is known for his work as a dancer and choreographer, but this exhibition emphasizes his multidisciplinary approach to art. Could you talk about Ailey’s influence beyond dance and how this exhibition aims to capture that?

AE: Once I really got into the archive and I listened to Mr. Ailey’s interviews and read his notebooks and read a bunch of dance scholarship, I realized that the very things he was talking about were things that were everywhere for a very long time. Not only within black American culture or black diasporic culture, but even in American culture more broadly. I realized that there’s a way in which these very things he’s putting forth are shared by all of these different people, and that it happens across time.

Once I got in the notebooks, and went through his interviews, I could see that he had a deep preoccupation, not only with literature, including novels and poetry fiction, but also a deep love of visual art. There were so many different references to the visual arts. In my conversations with Judith Jamison, Sylvia Waters, and Masazumi Chaya — the people who danced with him going back to the sixties — it was very clear in their comments that he encouraged them to go to art museums in all the cities to which they traveled for their various performances.

Edges of Ailey (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, September 25, 2024-February 9, 2025). Courtesy of Whitney Museum of American Art; Photo by Natasha Moustache

(AE continued): In Mr. Ailey’s notebooks are these taxonomies and reflections. The taxonomies were really telling, because that’s where he would list names of people and whatever he’s thinking about or reading. Then he puts them in relationship to each other, because he’s clearly building on an idea for a dance and wants to turn towards all these different folks to get there. Three references come to mind in particular. One is that he described the dances as ‘movement full of images.’ And I was so struck that he would characterize it that way, that even though it was about the body and about choreography, it was also about image making. In an interview he mentions that he was a painter, he wrote poetry, he wanted to write the great American novel, and that the dances are somehow all of those things for him. I thought, ‘we’re off to the races, this is great!’

So I took the themes that are in the dances which he said the work is about, and I started constellating other artists around them. In some ways, we end up with the ‘greatest hits.’ There were even lot of paintings that I have only seen in Art History books. We were able to bring some of the greats to be there alongside Mr. Ailey. It was very important for him to arrive at the Whitney not alone.

Jordyn White, Edges of Ailey (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, September 25, 2024-February 9, 2025). Courtesy of Whitney Museum of American Art; Photo by Natasha Moustache

DB: How did you select the works from this wide range of mediums that best represent Ailey’s expansive artistic vision and his impact on contemporary art?

AE: The works date back as early as 1851, and some are made especially for the show. It speaks to the profundity of these motifs — they’re so sustained and so important to such a wide range of artists, even when it’s not obvious. It’s actually very compelling when it’s not so obvious. They all work in different styles. There’s portraiture, abstraction, conceptual art, photography. There are self taught artists working in a very black American, Southern vernacular tradition. They are all displyed alongside one another.

DB: Ailey’s work is deeply rooted in themes like the Southern imaginary, Black spirituality, and the experience of Black migration. How does Edges of Ailey explore these themes, and why are they important to understanding Ailey’s legacy?

AE: The show is divided in two different ways. On one hand, there is an anchor around the American South. On the other, it is a broader diasporic investigation. It looks at the west coast of Africa and African culture, which is represented by drums. If you take an Ailey class you often start by listening to live African drumming so you can find your individual expression in the breaks between the rhythms. It’s important not only to the way he has taught choreography and the company teaches, but also to this historical relationship to West African culture.

Then you have Haiti — you see this across the show, where things are in one location, but reverberate and relate to other sections in the show. Haiti is an icon as the only country in the Americas in which the enslaved overthrew their colonizer and created their own country. Haiti is still repaying France for the fact that they were successful. Culturally it has a place in terms of how we imagine the possibility of what Black liberation is. Haiti, the Caribbean more broadly, and even Bahia, Brazil, are very important symbolically because they are places that have retained strong tensions in terms of African culture, spirituality, food, — many facets of Black expression.

installation view of Edges of Ailey (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, September 25, 2024-February 9, 2025). Mickalene Thomas, Katherine Dunham: Revelation, 2024. photograph by David Tufino

(AE continued): Going back to the nineteenth century, questions about liberation from enslavement come forward. These are sites that are looked to by Black Americans in terms of their painting and sculpture. There’s something about an imagination. Many of have them never been there before, but are imagining and situating themselves or scenes in their work.

We have this indexed through other artists in the Southern Imaginary section. For example, Loïs Mailou Jones is a Black American who taught at Howard University for many years. She is a wonderful artist and a very important figure in the Harlem Renaissance and also the Black Arts Movement. She taught in Haiti for almost a decade. She would go back and forth. She made a range of works that are stylistically different. We found an entire folder of research material by Mr. Ailey in which he imagined a dance around the Haitian figure Henri Christophe who had been a revolutionary in the Haitian Revolution, which we have on display. There was also all of this research from Brazil, looking at the Candomblé and at Samba.

We have that material paired with another Black American who’s gone Bahia, David Driskell, a very important art historian and artist who made these abstract paintings and drawings that are based on his time in Bahia. He went three times in the eighties, the same time that Mr. Ailey was going there. David Driskell’s imagining of Bahia are paired with these wonderful dresses and costuming that the women wear. Then we have Ruben Balanchine, who’s an amazing artist from Bahia. He was a dentist who became a practitioner of Candomblé and turned to making a beautiful symbolic paintings related to it. So you can see all of these entanglements.

Installation view of Edges of Ailey (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, September 25, 2024-February 9, 2025). From left to right: Kara Walker, African/American, 1998; Elizabeth Catlett, I am the Negro woman, 1947; Elizabeth Catlett, In Harriet Tubman I helped hundreds to freedom, 1946; Elizabeth Catlett, In Sojourner Truth I fought for the rights of women as well as Negroes, 1947; Elizabeth Catlett, In Phillis Wheatley I proved intellectual equality in the midst of slavery, 1946; Karon Davis, Dear Mama, 2024; Geoffrey Holder, Portrait of Carmen de Lavallade, 1976. photograph by Jason Lowrie/BFA.com. © BFA 2024

(AE continued): In terms of the American South section that leads into the Black Migration section. Mr. Ailey’s mother and her family were sharecroppers. He himself picked cotton. You’ll see a lot of references to cotton. We went to Rogers, Texas and shot video with the wonderful filmmakers Kya Lou and Josh Begley, who worked with me on this piece. They shot this cotton field that just went on for acres and acres and acres. For all we know, it’s the same land that Ailey’s family would have worked on, that he himself might have picked cotton.

We also have Beverly Buchanan’s shacks this a little village, and a nod to Mr. Ailey writing about the kind of home he grew up in and the extent of their poverty, which resonates with what Buchanan’s shacks look like. But then, in the forties, his mother decides to move to Los Angeles for better prospects, and probably because she knew she had a young gay child. It’s there that Ailey, in high school, studied gymnastics and meets Carmen de Lavallade. She takes him to his first dance class, which was at the Lester Horton School, which was the only integrated dance company in this country at the time.

While he was in high school, saw Katherine Dunham’s Tropical Revue. Dunham is an anthropologist who did the majority of her field research in Haiti. She is the first to use Haitian ritual dances and combine them with modern dance to evolve what we know of as Black Modern Dance in this country. It’s incredible when we think about these entanglements. Ailey hears Duke Ellington for the first time, he sees the Ballets Russes, and all of this sets into motion what he would become.

installation view of Edges of Ailey (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, September 25, 2024-February 9, 2025). photograph by Jason Lowrie/BFA.com. © BFA 2024

DB: The exhibition includes live performance programs and a residency by the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. How do these live elements enhance the experience of the exhibition, and what role do they play in conveying Ailey’s legacy?

AE: They’re important because there parallel to the show. There’s a total of over ninety performances that will have taken place by the time we finish. It’s enormous. Ailey’s in residence one week every month during the run of the show. So a total of five times. Then there are a group of choreographers who have been commissioned to show new work on the occasion of this project. Those eleven and their collaborators are happening in the weeks that Ailey is not in residence. They were selected by a dance advisory committee that included myself and eight other people from the Ailey company. It was an incredible process, and we took eight months to look at all of these different choreographers and to get that list down to the eleven.

DB: What do you hope visitors will take away from Edges of Ailey? How do you see this exhibition contributing to the ongoing dialogue about Ailey’s place in the broader history of American art and culture?

AE: I’m probably the last person to answer because I’m so in it! I think what would be important is that people do come to understand them not only in relation to dance, but also in relation to a visual art world. That they will understand the complexity of all of the ideas, influences, and surprising sources of material that actually influence his dances. I hope that they come to see him as a singular cultural figure, and thereby makes them look at all of American culture a little bit differently. And they should marvel. They should have, more than anything in that space, a fantastic experience.

project info:

exhibition title: Edges of Ailey

museum: Whitney Museum of American Art

location: 99 Gansevoort St, New York, NY

curator: Adrienne Edwards

on view: September 25th, 2024 — February 9th, 2025

happening now! thomas haarmann expands the curatio space at maison&objet 2026, presenting a unique showcase of collectible design.