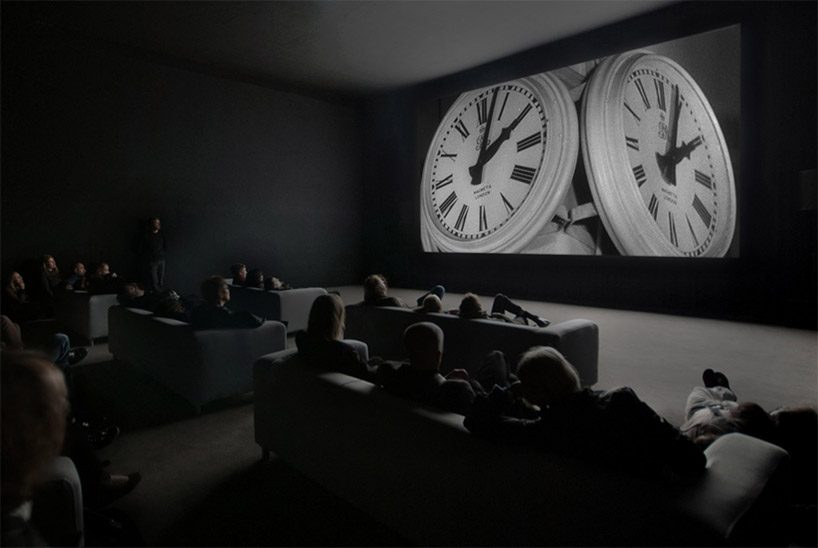

eight years after its premiere, ‘the clock’ finally arrives at the TATE modern in london where it will be screened until 20 january 2019, including an overnight 24-hour screening on 1-2 december! the california-born, swiss-raised and london-based marclay, originally debuted the acclaimed installation at the white cube gallery in london in 2010. the looped supercut is a 24-hour montage of thousands of film and TV clips of clocks, edited together to show the actual time (to which it can be locally synchronized). playing to huge crowds across the world since it’s first release, it has become the most popular video art work ever and also won the coveted golden lion award at the 2011 venice art biennale.

video still © christian marclay, courtesy of white cube gallery

soon after its premiere in 2010, paula cooper gallery and white cube offered ‘the clock’ for sale in a limited edition of six, and one was bought jointly by the centre pompidou, paris, the israel museum in jerusalem and london’s TATE modern. marclay worked tirelessly on the acoustics of the installation, assisting with curtains and carpets, and therefore had previously declined to screen it in the TATE as the turbine hall’s acoustics would interfere with the carefully edited soundtrack. now, with the new blavatnik extension, there is finally an ideal setting in the TATE for marclay’s meticulously edited art-piece.

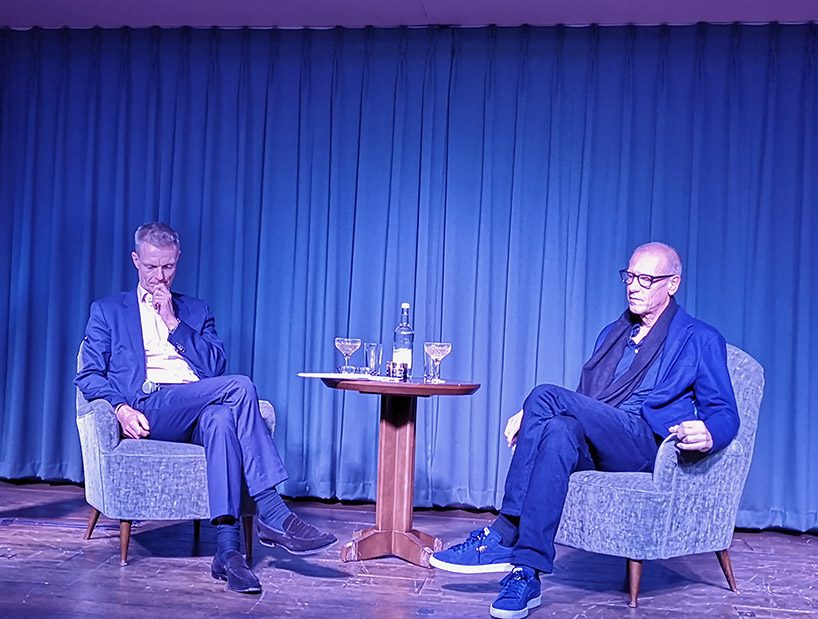

’60 minutes with christian marclay’, BMW art talk with tim marlow and the artist (right) during frieze london 2018

image © designboom

during frieze art week 2018, the historian and artistic director of the royal academy of arts, tim marlow, moderated the BMW art talk — ’60 minutes with christian marclay’. presented earlier by tim marlow, designboom gained further insight from christian marclay into some of the main themes behind ‘the clock’, and his other artwork, ahead of the TATE screenings.

‘the clock’ is a meditation on time

video still © christian marclay, courtesy of white cube gallery

we would like to explore the origins of how ‘the clock’ (2010) actually came about. at what moment and how did the notion of doing a 24-hour artwork that was a timepiece but also a montage of moments from films, when did that crystallize?

christian marclay (CM): well it took a long time before I actually started to work on it. I was moving from new york to london, following my wife, who got a good job there. I found myself not having a real studio and not quite sure how to get to work. it’s always the challenge as an artist because you don’t necessarily have an office to go to… thank god. but it’s still a challenge and so I had a lot of time on my hands. 5 years prior to moving, I didn’t think it was possible, and I was full of doubts. I didn’t really know if it was possible to find every minute of the 24-hour cycle within the history of cinema, within 100 years of cinema. at that time, I was working on a project called ‘screenplay’ which was about the process of making music live and I wanted to mark time – important for musicians -, and so I looked for some footage of clocks in films. yes, that was the initial idea, me and my research assistant watched films all day.

someone has to do it.

CM: the material was stored on computers. I had an AM computer and a PM computer.

the great idea of ‘the clock’ is that you will never have enough time to see it all

image courtesy of white cube gallery

so, it is a timepiece but it’s also a history of cinema. and cinema is a construction, film is a construction, and one becomes aware of watching it … what was your visceral response when you actually saw it?

CM: the fact that it is in real time and you become, the viewer becomes a participant in this experience, it’s almost like a performance. it’s not just a video that you watch and you’re separated from. it’s neither the engagement that you have with an action movie where you kinda get sucked into the narrative and you forget about time. this piece is really engaging you in the present. you’re there, you know exactly how much time you’ve spent in the video. you know when you arrived, you know when you left and actually that’s when it starts. you might never see the whole thing, its 24 hours and you can’t just, you know, spend all that time there. you have to eat, you have to feed your kids or the dog, water the plants… there’s so many things we have to do. go to the office.

still from ‘the clock’ © christian marclay, courtesy of white cube gallery

what’s interesting in the endless leap of the 24-hour cycle, that here are jump cuts. the viewer gets into the narrative, then is disjointed and thrown somewhere else, then you pick up the narrative again… was it kind of a random procedure or were you able to find enough material to control that?

CM: some minutes I might have just one shot at the clock at a certain time, but others, especially at the top of the hour, I had many choices. in cinema, midnight or noon are quite popular. but finding many alternatives for 5, or actually 3:30 AM, is a bit harder. especially 3:32, so there is actually within that minute a lot of room for me to express myself. I think there’s a lot of me in that project.

is there an obscure time of day that you can personally recommend us? should we be getting up at 2 o’clock in the morning? is there something there?

CM: I like the early morning, anytime after 5 AM. that’s when people in the movies, in real life too, start waking up (not in the art world, they don’t. no, real people…). the alarm clock starts ringing and it’s the morning I feel as the time when you can identify the more strongly with what’s happening on the screen because you’re physically tired you’re just starting to kind of trying to get on with the day. the clock is very much about that identification, that physical bodily response to the clock is when someone yawns on the screen and then you have to yawn because you’re living it. that’s the best part.

enough movies tend to be all about action. in ‘the clock’, time becomes tyrannical because almost without exception no one looks at a watch or a clock with pleasure. it’s something that’s impending, you’re about to miss something, you need to be somewhere to do something…

CM: maybe this is overstating it, but there is that kind of tyranny there. yeah, mostly time is shown in the movies as an anxiety-filled moment. I mean that’s what time does, or the way we structure our time. we have deadlines and we constantly need to keep up with it. also a lot of footage is about waiting for something. waiting to act. it’s that strange moment where you can’t do anything because time is going to decide for you somehow. I was interested in all these lull moments in the movies where people are at a cafe just waiting for someone on a date or something to happen or just you know waiting for a bus, that kind of, you know, where it feels like wasted time.

in ‘telephones’ (1995), christian marclay created a seven-minute, pre-youtube video collage of people in films making phonecalls

what’s the longest span you’ve ever watched ‘the clock’?

CM: I don’t watch it. I mean, I’ve edited it all so I know it by heart. I haven’t seen the morning, but for 8 years I’m trying to do that. a lot of people have claimed they’ve seen it all. people go back and they try to make sure they saw every 24 hours of it. I don’t like to think of ‘the clock’ a marathon piece. just see it a couple of hours here and there. that’s for me what’s important, it’s just how do you fit it in your schedule, that struggle is important to the work. unlike a film where everybody comes in at the same moment, collectively in rows, we sit and we don’t dare get up because we know that the whole row is going to have to get up for us and there’s this disruption. ‘the clock’ is about you making choices: you can come in at any time, leave at anytime. you make, you have to make these choices, which in cinema you don’t.

could you explain how the sound works as binding force of disjoint moments in ‘the clock’?

CM: sound is magic in a way because you can take different sounds and put them together and they become one. you can’t do that with images. in the process of making ‘the clock’ I realised how talented all these editors were, to make you believe that you’re watching one action and one space at one time. in fact, actors are being shot at different times, they don’t necessarily follow the continuity of the narrative but the practicality of the space. I’ve always been fascinated with our separation of the senses and how one is more subjective than the other. I’ve been interested in how one expresses the other — how to make sound with images or how can an image express or suggest sound. a lot of my work has been about this dialectic. we are so much more visual consciously, but in fact the sound plays such an important role in our experience of the world and you know we say an image is worth a thousand words but sometimes I’d like to think the other way around.

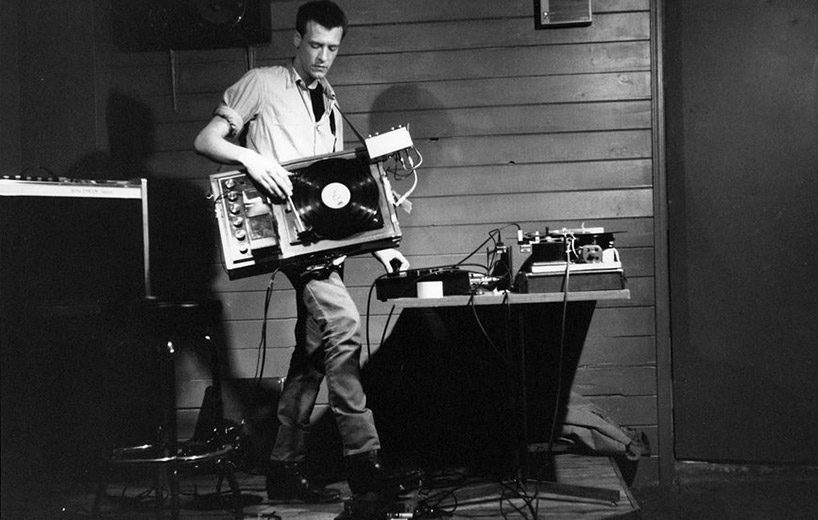

christian marclay performing on his phonoguitar in the 1980s

you often refer to duchamp and the found object. the language of appropriation and collage is still contentious in the era of copyright. how problematic has it been for you to sample thousands of film images, because we might as well be clear about it, they’re not copyright cleared…?

CM: yeah, well, I mean if you do something interesting, people will enjoy it. I think if you do something that’s not offensive, chances are pretty good that it would be qualified as ‘fair use’ which is a kind of north american term for that kind of appropriation. in europe it’s slightly different, there are laws where you have the right to quote but then you have to cite. I’ve been appropriating since ever. since I was cutting out magazines as a kid and collaging them. I’ve always been interested in the found, never interested to create something out of nothing. I mean even if you’re carving a piece of marble, marble is something and what does that mean? I’ve always been interested in pop culture and how the stuff that we use everyday that we don’t think about can be appropriated, transformed and maybe make us think about what it means and to be a bit more critical about what we do everyday. I think it’s always great to be able to marvel at what we do on a daily basis, things that are not important. I think duchamp was always very interested in the tiny little gesture that we never think about because it’s so damn banal.

los angeles, 2003

los angeles, 2003

© christian marclay, courtesy of white cube gallery

video still of ‘guitar drag’ (2000)

© christian marclay, courtesy of white cube gallery

seeing a musical instrument being mistreated or destroyed provokes strong reactions. in 2000 you’ve featured a fender stratocaster being dragged behind a pick-up truck along rough country roads in texas. can you tell us more?

CM: the video is called ‘guitar drag’. while on one level it’s an expression of my interest in creating a new sound, it is also referencing some of the guitar-destroying rock stars of our past – as well as it is triggered by the murder of an african american called james byrd in jasper, texas, where he was tied to the back of a truck and dragged along until he died. I tied an electric guitar to the back of a truck and for 14 minutes dragged it around. it’s a violent piece that starts as a comic one. the sound is quite violating.

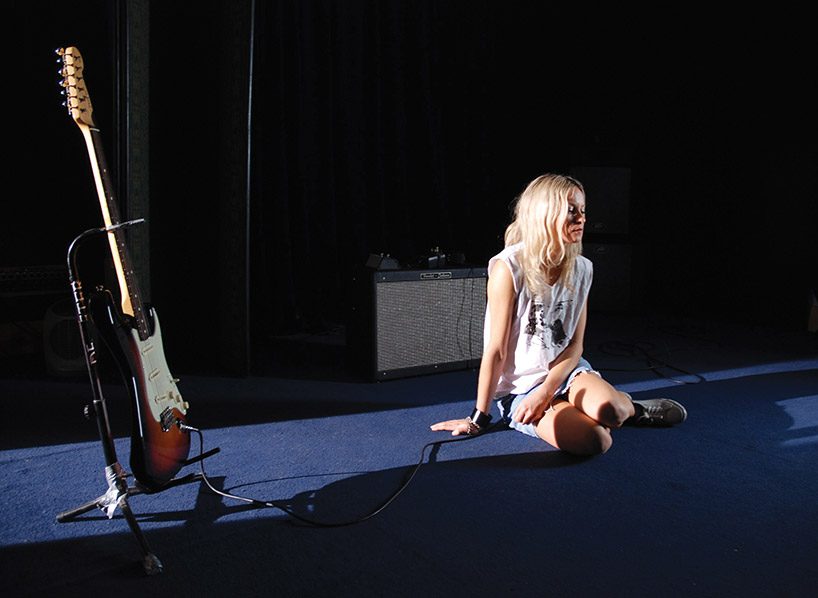

video still of ‘solo’ (2008)

© christian marclay, courtesy of white cube gallery

earlier, in another extraordinary piece ‘solo’ (2008) you are showing what a guitar becomes. guitars have a sort of erotic rock and roll history and you have shown a woman using a guitar as a substitute, she is masturbating, she is rubbing herself against it…

CM: I’m a male artist and I’m portraying a woman masturbating with a guitar. but the actress was really into it and she felt empowered by this and I got a lot of positive feedback from women who felt the same because the guitar is mostly associated with the male performers. it has a masturbatory quality, it is very phallic, it’s very anthropomorphic. the guitar has always been associated with the body, the body parts of the guitar, the neck, the body. often blues players will call their guitars by women’s names. I haven’t shown this piece in a long time it would be interesting to show it now to see what kind of reaction. today it doesn’t seem to be an issue. it’s very interesting how culturally at certain times you can do things that at other times you can’t. if you think back to when duchamp painted his ‘nude descending a staircase’, and it was a scandal, you wonder why. another thing, guitar drag would be more controversial today because I’m a white artist referencing the lynching of a black man and people have become very defensive. you can only talk about your race and someone else’s race, which I think is a sad thing. we should all be able to identify with others regardless of race.

about BMW group’s cultural commitment

for almost 50 years now, the BMW group has initiated and engaged in over 100 cultural cooperation’s worldwide. the company places the main focus of its longterm commitment on contemporary and modern art, classical music and jazz as well as architecture and design. in 1972, three large-scale paintings were created by the artist gerhard richter specifically for the foyer of the bmw group’s munich headquarters. since then, artists such as andy warhol, jeff koons, daniel barenboim, jonas kaufmann and architect zaha hadid have co-operated with BMW. in 2016 and 2017, female artist cao fei from china and american artist john baldessari created the next two vehicles for the BMW art car collection. besides co-initiatives, such as BMW tate live, the BMW art journey and the “opera for all” concerts in berlin, munich and london, the company also partners with leading museums and art fairs as well as orchestras and opera houses around the world. the BMW group takes absolute creative freedom in all its cultural activities – as this initiative is as essential for producing ground-breaking artistic work as it is for major innovations in a successful business.

happening now! thomas haarmann expands the curatio space at maison&objet 2026, presenting a unique showcase of collectible design.