designboom interviews thomas heatherwick

image © rosie hallam

since founding his own studio in 1994, thomas heatherwick has emerged as one of today’s leading thinkers in the field of design. working from a combined studio and workshop in kings cross, london, heatherwick’s growing team now includes 180 individuals. at the heart of the practice’s work is a commitment to finding solutions through a working methodology of rational inquiry, undertaken through collective experimentation.

the studio’s realized work includes the UK pavilion at shanghai’s expo 2010, the olympic cauldron for the london 2012 olympic games, and the transformation of a paper mill into a striking gin distillery. the success of these projects, among many others, has lead to larger commissions, with heatherwick currently working alongside norman foster on a mixed-use destination in shanghai, and collaborating with bjarke ingels to develop google’s new california headquarters.

designboom recently spoke with the designer who explained why he wanted to become an inventor when he was younger, the projects he is currently working on, and why he relishes a collaborative working environment.

bombay sapphire distillery, UK / image © iwan baan

see more of this project on designboom here

designboom: your work spans many different disciplines. can you talk more about the ideas that interest you?

thomas heatherwick: when I was little there were some books I got given of old patterns from edwardian times, and I always find it quite mesmerizing to go through and see all these ideas that were trying to solve a problem, but they also had this aesthetic quality to them. so I grew up wanting to be an inventor, but then I discovered that you can’t study inventing. the world of inventing was chopped up into all these different areas, and the thing I found useful about that is that there is always some kind of problem — something you perceive to be a gap or a loophole that you can fill. we lose track sometimes of what the objective is. if you can’t describe what the problem is, designing means nothing. critiques and problems sound negative, but to us it’s a positive thing, and helps guide us.

google mountain view campus / image © heatherwick studio + BIG

see more of this project on designboom here

DB: finnish architect alvar aalto was obsessed by detail, so he continuously went to check everything concerning his projects. today it is a little bit different, you are working in many places in the world, so how often do you have the chance to see what’s going on as the project is being built, can you still have an influence on the details?

TH: my role is to keep focus for everybody, and to champion and keep pulling your brains back and everyone’s brains back on to the object and the problem you are trying to solve. there are infinite amounts of possibilities for things to go off in funny directions.

we don’t blindly trust anything other than the physical. I feel very strongly that what we do is the physical, and there is excitement about what the new technologies can do, but I don’t think many people have made more complex geometries than were made centuries ago by people who didn’t have any of the technology that we have now. you look at some of the geometry that gaudí was working with, and the great cathedral builders, and you know that now it would be trumpeted as ‘computer design triumph’, but there was no computer design involved. they are just tools, but it means that me and my team are engaged all the way through. if you can really have the right relationship with those around you, when that works well, that’s when a special project can really happen, but you depend on everyone else as they depend on you. it’s not just you or it’s not just them, it’s that management of complexity that I find fascinating, and endlessly challenging.

bund finance centre, shanghai / image © foster + partners

see more of this project on designboom here

DB: can you talk about any projects you are working on at the moment?

TH: one is a large project on the bund in shanghai where we are working with foster + partners. we are designing it 50/50, and it is currently nearing completion. another shanghai-based project we are doing, ‘moganshan’, is at the M50 art district. this one is 300,000 square meters — nothing is small in china! so the challenge, more than ever, is human scale. because there is this massiveness, but we are still roughly the same size we were 1,000 years ago. I find that interesting – how to make details, variety, and enrichment.

moganshan development, shanghai / image by mir

see more of this project on designboom here

DB: are there any particular problems you encountered in terms of the scale of these projects?

TH: every project is challenging. we have been working on those projects for four years, and they’re at different stages of construction. I feel very lucky to have had the chance to work with city officials and with the planning offices, and people who really wanted to do something special. I never realized how influential being chosen to do the british pavilion (for the shanghai expo) would be. it was very different than if that project had been in britain, because british property developers are a little bit set in their ways about how things are done. I felt that the response from chinese city officials, mayors, and developers was much more open.

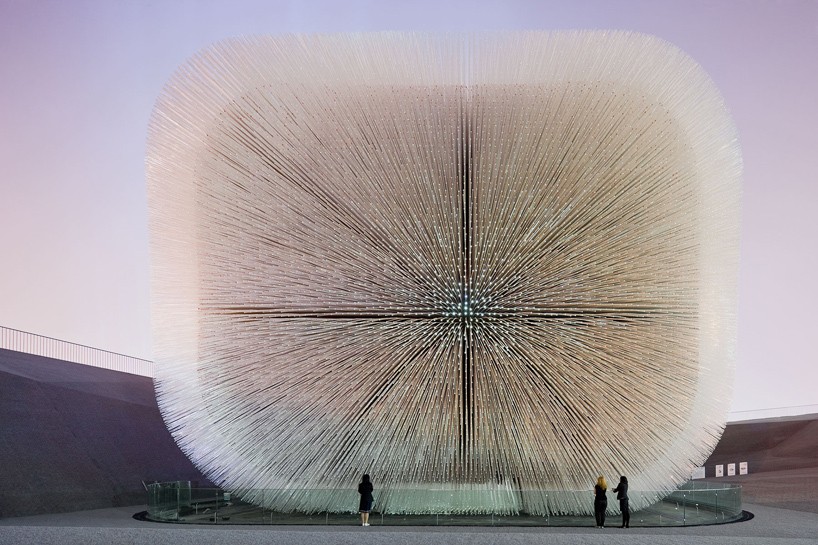

the UK pavilion was rationally conceived — there were 250 pavilions, and we had half the budget of the other western nations. we had to anticipate how a human would feel at an expo which is the size of a whole city. when it won the top prize, it was because of the analytical work we did and the very precise use of the budget we had. I think the british mindset is learning things from the way others are working around the world. we just had incredible conversations with people, which are now turning into these completed projects. we have had, in turn, a chance to learn ourselves, and carry through thoughts that for many, many years we had been thinking about.

UK pavilion at shanghai’s expo 2010 / image © iwan baan

see more of this project on designboom here

DB: do you feel there is an enthusiasm in china that people want to have projects that really stand out?

TH: I feel that the expo happened at an interesting time in that there had already been this big opening up of china. there had already been this explosion of new construction, and there had already been an initial burst of excitement. the first wave felt like it was much more a duplication of things from other places. the people we were meeting were people who were looking at this first wave with critical eyes, and feeling that — while appreciating that things were happening — that there was a sense that china didn’t need to copy other places. and now there’s this interesting second phase, where china is wondering how to do things that particularly relate to their incredible historic civilization. that’s a process we are all in, and I feel very privileged to be on that voyage. I hope my studio’s objectivity is used for that partnership as we learn from our collaborators here.

garden bridge, london / image courtesy of heatherwick studio

see more of this project on designboom here

DB: can you explain how you are influenced by nature and how it is integrated within your designs?

TH: I don’t have a single philosophy of the world that is a mono-approach. everything around us is designed — everything. so having something that changes and evolves and has its own life and its own seasons is a balance to the manmade. we have been interested in the integration of nature in some of our projects. for the garden bridge (in london), even if we created an enclosure, there is a different feeling when there is something that feels ‘not designed’. nature also replenishes its own surfaces, and keeps generating a new skin like a chemical peel.

aluminum paneling and perfect shiny flat glass have their place, but it is a counterpoint to that. most of the projects I’m working on are public projects, that’s my passion. I think that one of the things the victorians and the georgians did in the united kingdom was they made british cities the greenest of their size in the world. they put in parks, heathlands, street trees, squares, front gardens, private back gardens, and that gives a sense of humanity somehow, and softens what can otherwise be very harsh.

a recently released winter rendering of the garden bridge / image courtesy of garden bridge trust

DB: as a designer you have stated we should be passionate about the projects we work on — and that if we’re not, then we should be doing something else. have there been any decisions that you have made that allowed you to work from that position?

TH: I’ve been going for 21 years, and for the first 15 I was very frustrated. it takes a very long time to be trusted to do the kinds of projects that we’re working on today. nobody just takes a 24 year old and says ‘why don’t you work on a 3 million square foot development’. you have to be very patient and very determined. I’ve been going for that time, but the singapore learning hub was one of our first completed buildings with elevators and fire stairs. did I want to do that 15 years ago and desperately want someone to commission us to do that? yes, but you have to just keep going and that’s the challenge. it’s always hard doing things, there’s never an easy moment. I think it’s easy to project onto others that they’ve had some kind of luck.

learning hub, singapore / image © hufton + crow

see more of this project on designboom here

(continued) I knew when I was studying that nobody got grabbed at the end of their degree show and was suddenly shown the stars. so I already started planning when I finished my masters degree, how I could live and work in the same building to keep my costs down. I didn’t know who to work for, so I thought I’ve got to work for myself, because I don’t know anyone who was working in that niche that I was interested in. it feels so recent in a way for me, leaving college, and it goes so fast. I was never good at sprinting, but I could do long term endurance. I think that working on a project that is going to take six years to build, you just have to be really determined, and not lose heart. so you need to enjoy the process, and be excited by the potential outcome in order to fuel the dark days that it takes to get to that point.

the project is one of heatherwick’s first realized buildings

image © hufton + crow

DB: when you were younger you saw this gap in the field of design. do you consider your role different now?

TH: in a sense I feel like I’ve only just got going. as I said, I’ve only just finished one of my first proper buildings after 21 years. would I like to design more than that? yes! the UK pavilion, for example, no one did things like that, but now the serpentine does a pavilion every year, architecture courses do things like that… so in a way it’s exciting to feel that we were on to something, and it encourages us to believe in logics that we perceive, because I think people need to trust their intuitions.

I am always interested in the gaps, and when you have brilliant people doing something you think: ‘there’s already brilliant people doing that kind of thing, so I’ll do something else’. that’s always been something I’ve been very aware of, and there are some very talented people. there are probably more talented people in the world of designing buildings and environments, than there are good people to commission them. so that’s always the challenge, finding the people that have an ambition and a vision for what something could be. you completely depend on the vision of your commissioner — you end up getting all the credit, but it’s them who felt that there was something that could happen, and you’re part of achieving that.

maggie’s centre, yorkshire, UK / image courtesy of heatherwick studio

see more of this project on designboom here

DB: can you elaborate on how your studio works, and how the team comes together?

TH: I don’t come in with a sketch on monday morning and throw it down. I realized quite early on when I was studying that I didn’t work like that. in university it is very much about the individual student, and they are trying to do something brilliant. and I felt that I was okay, and I could do that. but there was an engineer who used to come in, and you would start talking with him and it was wonderful. you forgot who was the engineer and who was the designer, and together you could move ten times as fast.

‘inspire’ is an overused word, but I find people and conversation the thing that triggers my brain the most. I love that camaraderie, and the best projects we have worked on are the ones where I can’t tell you who designed what. I’m in the middle of it, working with everybody. my job is to make sure it comes together, and be the glue and the provoker for my team. one thing about taking your time, is that gradually you build up brilliant people around you, and that’s one of the things I’m really protective and proud of, and I’m trying to get better and better at understanding how to nurture those people.

pier55, new york / image courtesy of heatherwick studio

see more of this project on designboom here

DB: how do you find a balance between the fields of art and design?

TH: I don’t feel they are separate disciplines. I feel like the pieces of design that we really like have an artistic thinking in them. I think it is implicit that the best pieces of design are artistically, as well as functionally, technically, and socially, conceived. I don’t see them as two things to balance, but rather inherent to each other. I’m very interested in logic, but then also feelings, and how you mix the two. feelings are an important part of function. and I think people ask questions as if feelings are this separate thing, but it’s a function, how something makes you feel. I think we underestimate how much these decisions affect human experience, and you don’t have to study design or art history to perceive how something makes you feel — even if you can’t explain to a designer why.