at the 2020 engadin art talks (E.A.T.) in switzerland, mexican architect tatiana bilbao took to the stage to present a talk titled ‘how silence and sound shape the domestic space: the cistercian monastery as a form of living’. in the lecture, which can be seen in the video below, bilbao talks about her time at a monastery in lower austria and how she learned how to design for the monks that live there.

after her E.A.T. lecture, designboom spoke with tatiana bilbao to understand what she gained from talking with the monks and how she can apply this to other, more conventional projects. the mexican architect also explained how she approaches each project by putting herself in the position of its user, and why she loves to teach. read the interview in full below.

ventura house, monterrey, mexico (also main image)

image © rory gardiner (main image © iwan baan)

designboom (DB): yesterday, in your talk, you elaborated on what people want from a space. as you have to interpret it, you always thought it’s better to know the person as much as possible so you can understand their needs. however, then it changed a little when you saw, for example, the community of priests, with completely different needs. so it’s not so important to know every single priest or know their preferences, but it’s something about the absence of things to create space — the mindfulness. can you a little bit elaborate on this?

tatiana bilbao (TB): I don’t think it changed my mind in terms of understanding the needs of the others, but their needs are very different now. when I started working, I was working with projects that were smaller, so I knew the people that were going to inhabit them. as we got bigger and bigger missions, I started to do things where I did not necessarily know the people who were going to use them. what I always try to do is to at least integrate people that could be those who use them.

acuña housing prototype

image © tatiana bilbao estudio

TB (continued): for example, we did a house that was built with €8,000 — this is why people know about the house — but in reality it was because it is part of a program and all of the houses in this program have to be built without money — people cannot pay more. so this is the target, and there are hundreds of models. what we revolutionize is the idea of a modular design that can be used differently as this house is going to be repeated in thousands.

we don’t know who’s going to use the homes, but we interviewed people that could be. in the beginning we were designing and imagining that we knew about these people, then one day I said: ‘guys, we know nothing about the necessities of these people right now’. I was very happy to go because we never thought it was so important to keep the archetypal form of a house. this is something we found out when we did the interviews. this is why I really think that I will never give up on that, because I think it’s very important: we’re designing for others. when you are designing for others, you cannot become the other person. I wish, but you can’t. so within that impossibility, the best you can do is to try to think that you can become the other.

the house has a bright external finish with colored walls

image © tatiana bilbao estudio

TB (continued): the other strategy is to integrate more minds. with my filters, with my education, with my knowledge, with what I see, I definitely translate things in one way. but each of us do this differently. so with the same project, you will need to see totally different things. this is why I like to integrate teams, working with people that are not only my employees, because at the end, when it’s your employee, it’s your employee, and they’re going to agree at some point.

I like to integrate people from other backgrounds, from other professions, even from the contrary visions that I have, and in the case of the monks the necessities are different. it is a very intense individual need of a space that would allow them to find the highest achievement of intimacy, to create this possibility of connection with god, which is silence. the bare minimum is to have a real space where we can find our highest point of intimacy and silence in order to become social human beings. so I’m thinking that there is an important lesson here that could be extrapolated into housing schemes for living.

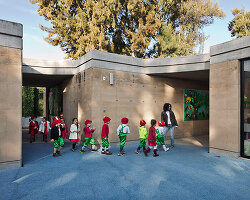

bilbao presented the prototype at the 2015 chicago architecture biennial

image © designboom

DB: do you see this approach as being different from luis barragán’s approach?

TB: what I see with barragán is his search for these moments. so in this case, the core thing, I don’t see differently. barragán was a monk himself, almost no? he was a person in search of this intimacy and in this really complete enclosure from the exterior at some point. I think his procession of spaces would allow you to do that, and the way he uses light in the spaces creates these moments where you are aware of another dimension — I think that barragán was searching for that all the time.

we are in the first stages of the monastery project so we are first trying to understand all the history behind it. I’ve been with the monks for three years. it is been a gift to have these years because monasticism is a life that you don’t understand. I love what I know, but I don’t think I will ever understand it because I’m not a monk myself.

DB: do they know what they need in terms of space?

TB: they have things way more clear than we do. they don’t have noise in their minds. they have this connection with god, and they are free of everything — it’s amazing. so they have things very clear and we don’t. we need to translate, so this is why the gift of time is precious in this project.

‘how silence and sound shape the domestic space: the cistercian monastery as a form of living’

video courtesy of engadin art talks

DB: before your talk, I did not really understand how much they need the community. we have the idea that they don’t want too much to do with it because they’re trying to live far from the daily trouble. but it seems it is so important for them to have a loving community?

TB: yeah, it is impressive. it’s absolutely necessary because you’re not self sustainable as a person so you cannot get all your food that you need. all the things that you need you cannot get them, especially on top of the life that they have, because they have this dedication to the prayers that takes up a long time during the day. so, they have to become a community. they have to share the activities planting their food, preparing the food, and cooking.

DB: and this will be part of your project?

TB: yes, this is the only way it works. this is why monasteries become communities. what is also interesting and can be extrapolated too in the way we live, is understanding these stages of relationships.

DB: which are maybe not so different from ours…

TB: they are the same, but I think that we haven’t understood them like that. especially in modern times, in cities, we’re missing these possibilities of understanding that we really need a set of people around to help us survive. I mean, now that I have kids I understand perfectly. they say that it it takes a village to raise a child. I would not say a village, but I would say it is a community of people that are around in order. with all of us, we take care of the kids, and we cook, and we clean, and then we can each develop our own lives. I think we have lost that especially in big cities.

you live in a huge apartment building where you know no one because there’s an elevator that sucks you into a floor with three doors, you enter your door and that’s it. and then you go out to the street and then there’s millions of people. how do you start relating to them now? then you go far away to your job, and you make friends there, but your friends leave also — who knows where? you then start to somehow create a little community with the parents of your kid’s friends, but it is not a tight circle of people that can really make your life.

DB: can architecture do something about this?

TB: definitely, because now we’re designing these individual spaces and then expelling people to the outer world. so what is the answer? I don’t know, but I am looking for it. I’m working on it, and I have understood that we have to work very clearly on it — I’m digging.

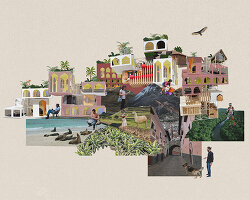

casa ajijic, jalisco, mexico

image © iwan baan

DB: are there some mexican architects that you’re particularly interested in the work of?

TB: I always find the work of mario pani very interesting. I live in a mario pani building and the older generation has done incredible things.

DB: you have said that you work in a very simple, archaic way. could you describe how your process is? as you already said, you involve people, do interviews as a kind of research, and you’re doing modeling a lot?

TB: yeah, we do. I don’t know how to use a computer for anything other than emails, and keynote presentations. now I know how to do very good keynote presentations, even with effects. the rest I don’t know. I also write by hand. I can understand why people use a word processor, but in terms of ideas, I think they should be translated into a physical reality, especially when they are a spatial thing. this is going to be a physical thing and it’s way more direct to think that the idea from your mind goes into some kind of physical representation, which is a drawing, or a model, or whatever, and then it becomes a space. the relationship is more direct. I think that the results at the end are better, and that everybody needs to do this translation.

casa ajijic, jalisco, mexico

image © iwan baan

DB: so you don’t do renderings and present them to your clients to give a graphic view?

TB: no, because in the beginning I started to do them and then I realized how damaging it was for the process. sometimes at the end there are clients that really need the render and really need the physical thing for the government to get the money, but it kills the process. I think the clients, or the people who are going to use the projects, stop thinking because the building is ‘done’. there’s nothing else to think. meanwhile, if you think you are in the process and you show these images to create a conversation and do a delivery, the client then says it’s done now, and when you evolve, because it is going to evolve, the client stayed there. I think this is very damaging to the creative process.

designboom visited bilbao’s studio in 2011

image © designboom

DB: overall, what would you say is your biggest strength? how have you developed that skill over time?

TB: I like the questions! that is hard to answer by myself, you tell me! what I like to think, not that it is my biggest strength, but what I like to promote is a constant dialogue or an openness to a dialogue that might bring me conflicts. the more conflicts, the better it is. conflicts or challenges — I need to be there. questions, lots of questions, and lots of unanswered questions.

DB: how come? did you experience architecture as something limiting? or you wanted to react against something existing?

TB: not a reaction. maybe it’s just a necessity, it’s my nature. I’m always like that and I’ve been always like that. to always question things and to go beyond and go a second time, third round, fourth round.

‘gratitude open chapel’ at la ruta del peregrino, lagunillas, mexico, 2011

by tatiana bilbao and dellekamp arquitectos | image © iwan baan

DB: as you are teaching, which is very time consuming, you must have the will to transmit something important. do you feel that it was important being a student, and you want to give something back?

TB: I think it’s a lot of things, but I love it. it is very difficult every time and I’m almost about to board the plane and I’m like: ‘why did I decide that this was a good idea?’ but the moment I enter the university I know why. I think the one very important and very selfish reason is that I learn so much. every time I’m there, I’m learning and more questions emerge. these students really challenge you in directions that the everyday wouldn’t challenge me and I like this very much.

the other reason is that I like to open channels for people. in the same way I like to be challenged, I challenge people and take them out of their comfort zone and bring them to troubled places. another reason that I teach in the united states is because I think there is very little knowledge of what mexico is in the US. I think in mexico, we have a very difficult relationship with the united states — a very tight and difficult relationship.

DB: I had a long discussion with pedro reyes about that.

TB: obviously now it’s been brought to light because of the president of that nation, but it’s always been like that. in mexico we have idolized the idea of the american dream. one of the reasons that I teach is because I want to bring out that other side of mexico and I also think that it’s important. we are now culturally, totally interrelated, and completely and totally dependent. so it is very important that we understand, especially architects who play a big role.

there are complete cities changing because of this relationship on both sides of the border. physically, the migrants are creating colonies in cities like in new york where there’s a neighborhood called ‘puebla york’. puebla is a state in mexico so now they call it puebla york because half of the population is living there, literally. they’ve transformed this neighborhood into little mexico.

tatiana bilbao | image by katalin déer, courtesy of engadin art talks

DB: is that with building permissions, everything regulated or informal?

TB: both, but yeah — they’re now part of this economy. for example, in kansas in the 1990s, the white population that existed in this little town of 11,000 people reduced to 6,000 very quickly because they they didn’t want to do these jobs anymore, but the jobs were necessary — working on farms where they rear cows and produce meat. it’s a horrible job so they decided not to do it, then they started fleeing out. all of a sudden, at the beginning of the 2000s they found themselves with 6,000 people. by 2012, there were 11,000 people again, but those people were mexicans. so this town transformed. the immigrants that come back have a totally different way of seeing their lives and then they’re changing towns, entire towns in mexico, because of where they’ve lived. we’re really curious.

E.A.T. / engadin art talks is an annual forum and festival for art, architecture, design, fashion, film, science, and literature which takes place in zuoz, switzerland. E.A.T.’s mission is to provide an interdisciplinary platform for a global dialogue on the arts and different creative fields. internationally recognized for its line-up of leading artists, architects, writers, scientists, and disruptive minds from all over the world, E.A.T. has invited so far more than 140 speakers that have presented their ideas and visions on challenging social relevant themes since its inception in 2010. E.A.T. was founded by cristina bechtler together with hans ulrich obrist.