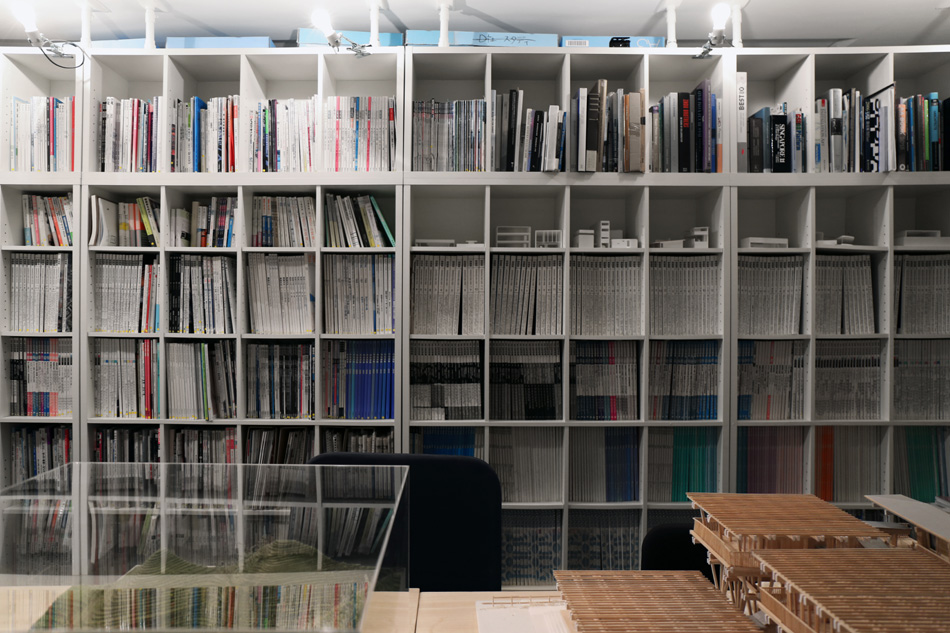

tezuka architects is a tokyo-based practice led by husband and wife team takaharu and yui tezuka. since its formation in 1994, the studio has completed a great number of residences, schools, and hospitals, all of which embody the firm’s belief in designing projects that embrace a natural lifestyle. on a recent visit to tokyo, designboom spoke with takaharu tezuka at the firm’s headquarters, where he explained what originally made him want to become an architect, his biggest influences, and why timber is his material of choice.

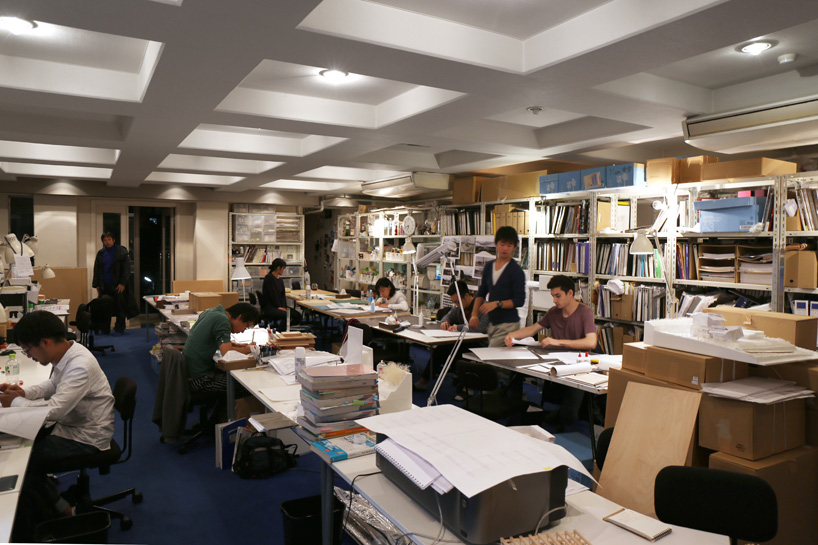

inside tezuka architects’ tokyo headquarters

image © designboom (also main image)

designboom: what originally made you want to study architecture and become an architect?

takaharu tezuka: both my grandfathers liked architecture so much. my mother’s father actually asked frank lloyd wright to design his headquarters, but it didn’t work out, as he was getting old. instead, he got one of his apprentices to work on the project — taro amano. also, my father’s father organized two gold medal winning buildings. my father was supposed to take over the family business, but he didn’t like the money making business, so he became an architect! my older brother was disabled, so he couldn’t become an independent architect, but he worked for the kajima corporation. the most important project he worked on was the imperial palace, he was a side architect on it. since I was small, I have been surrounded by models and drawings, so it was quite natural to become an architect.

the office is organized with a series of linear work stations

image © designboom

DB: what particular aspects of your background and upbringing have shaped your design principles and philosophies?

TT: the tezuka family house in arita had a profound influence on my architecture. the house was built about 100 years ago. the family was doing trade with the east india company, and they used to import different styles — art nouveau, art deco, these kind of things. consequently, the house had two aspects: one part was really japanese, and the other was very european. I think I got that kind of influence. there were so many interesting details, but until I went to london, we didn’t know that the house was so special. after staying four or five years outside of japan, I came back and I went to the house again, and realized that there were so many great aspects of the house. I think that house had the strongest influence on my designs.

also my father — he always talked about architecture. I was a third year student in winter school, I was nine years old, and he explained the structure of the world trade center towers. after september the 11th, my friend asked me how it happened, so I explained the structure. but the knowledge didn’t come from my studies, it came from my father.

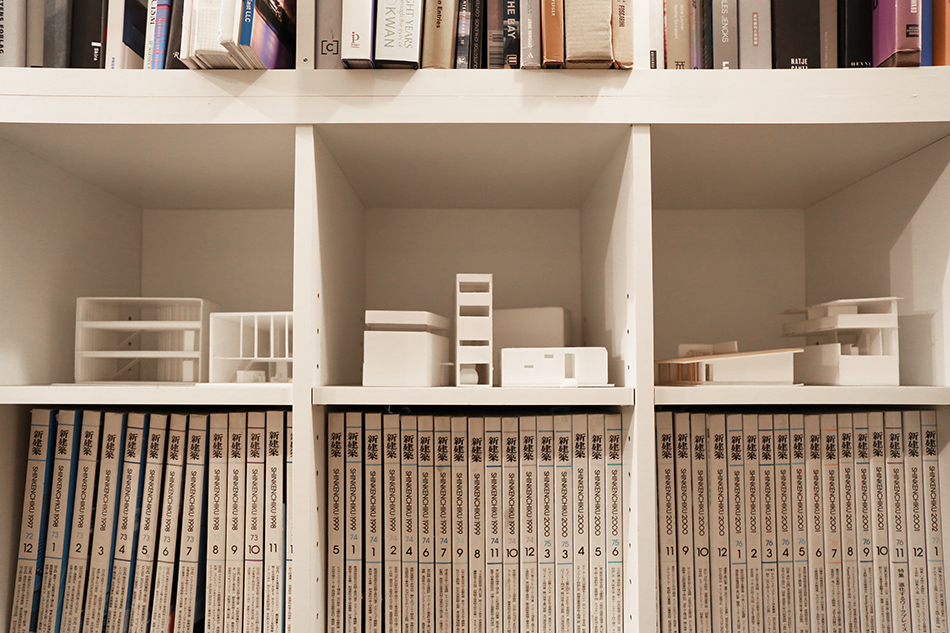

the desk where the firm’s models are made

image © designboom

TT (continued): another great influence was richard rogers, who I worked for in london. some people think he is just about high-tech style and high-tech details, but I don’t think so. he always talked about the lifestyle of people. we used to look down the river thames from the balcony of his studio and drink tea, it was so fun. I really enjoyed it.

one day I went to the top of his old office, which was a conversion of warehouses along the thames. it had this vault on top, which had a wonderful mechanism that brought out this triangular tent. I told him ‘it’s hot today’, and richard rogers said, ‘this is contact with nature!’. he always made a joke about these kinds of things, but that kind of feeling became the base of my thinking. I didn’t have much time to talk with him, but I think that short moment became a base of my architecture. it was a great moment. I was only there for four years, but the influence lasted a lifetime.

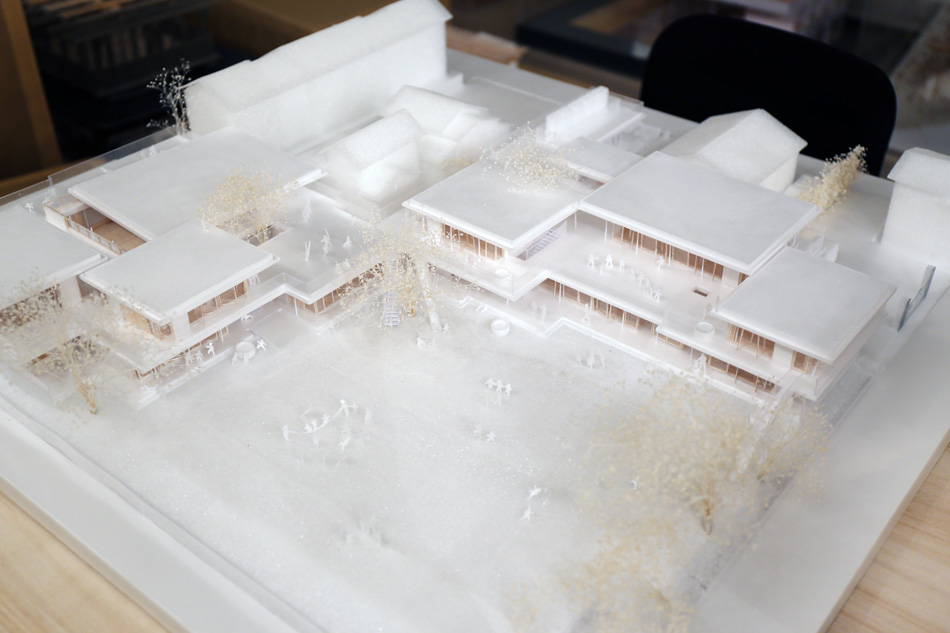

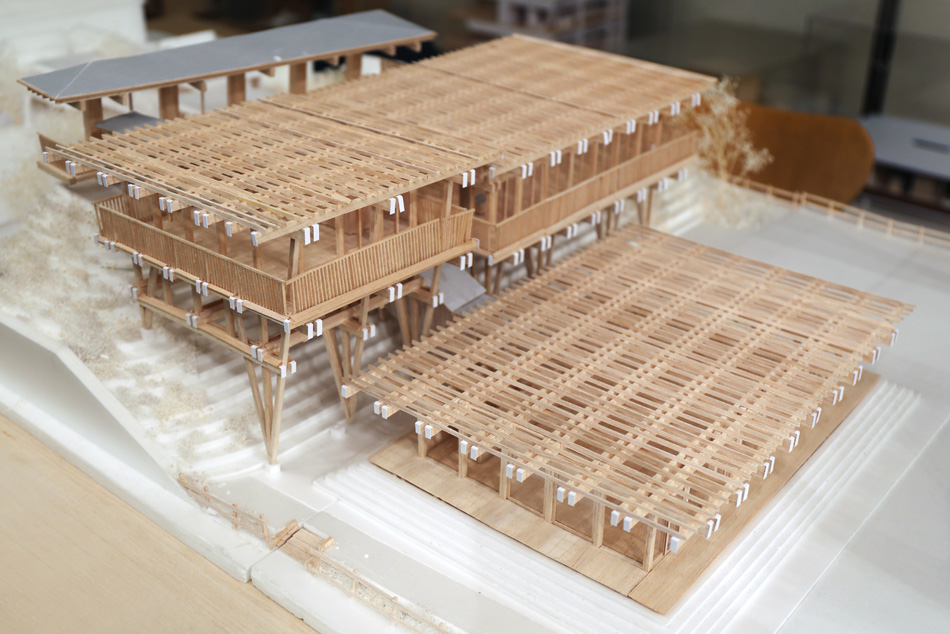

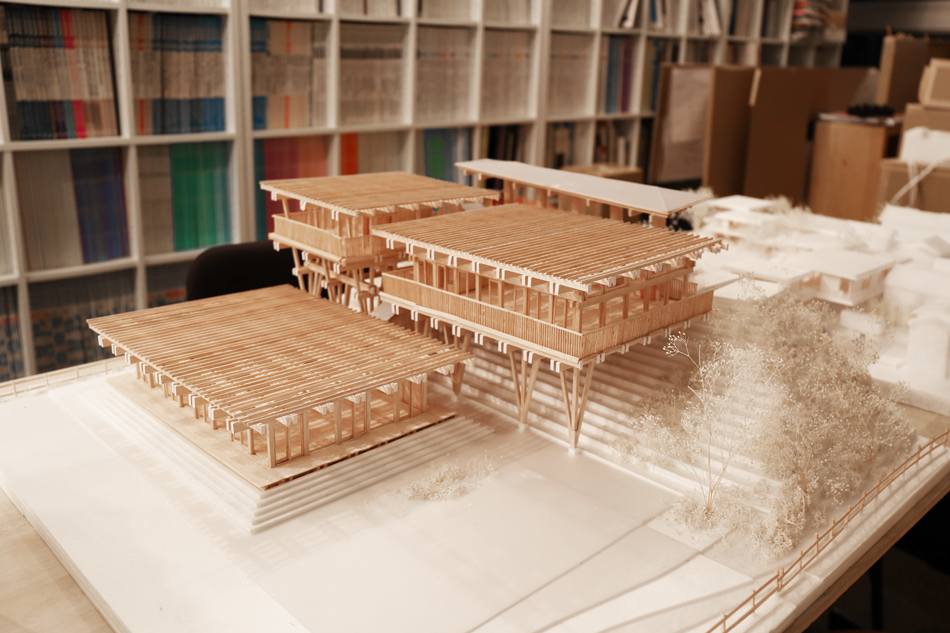

the studio continually uses models to develop its designs

image © designboom

DB: how important is incorporating a sense of nature and greenery in your work?

TT: it is my philosophy. I am very accustomed to the idea that we are part of all aspects of existence. architecture is not making something against nature, we don’t need to protect ourselves from it. so we try to find a way to appreciate nature. in europe, nature is something to overcome, but in japan it is quite different. we try to bring nature into the room.

I try to relate it to the story of sashimi. in the 19th century, a cartoonist in the UK drew a japanese lady with a kimono eating a live fish. it meant that everybody in europe saw the japanese eating live fish. we eat fish raw as it is — we don’t cook it sometimes — but it doesn’t mean that we are eating live fish! to get good sashimi you need a good knife forged by the craftsmen, and also a good cook. it needs to be treated properly, otherwise it doesn’t taste good. for scientists, sashimi is just fish meat. however, if you talk to sushi masters, they say that if you slice it into thin pieces it tastes sweeter, and if you make it chunkier, sometimes it tastes bitter. so by treating it in a different way, it tastes different.

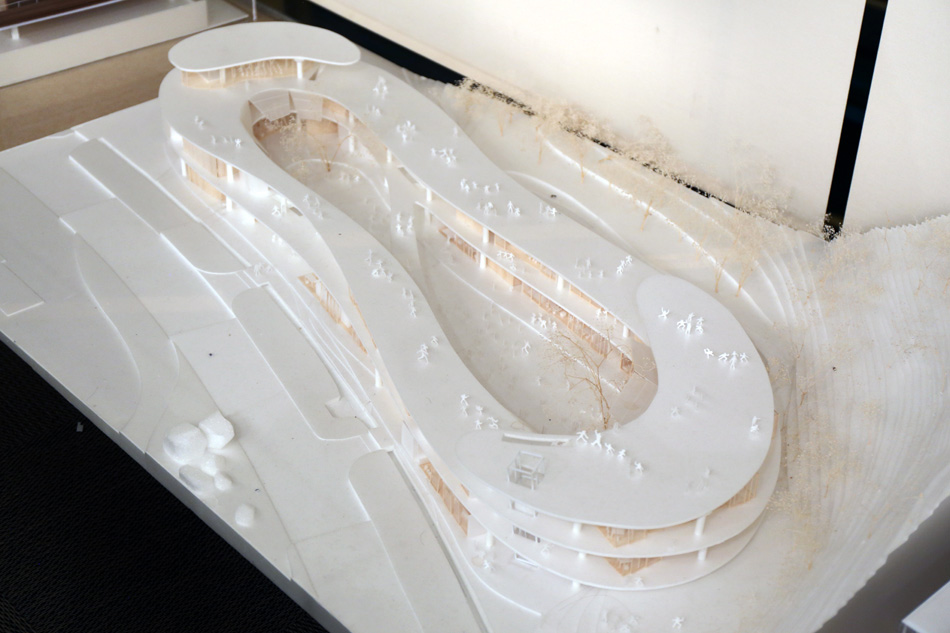

model of the fuji kindergarten

image © designboom

TT (continued): we are doing exactly the same thing with nature. we are trying to bring it in, but not as it is. for our ‘roof house’ project, sometimes people say, ‘okay, so you are just putting people on top of the roof. instead, you should put people on the field — it is much more open’. but we treat nature in a way that people can digest and appreciate. so if you look at the top of the house, you see it has walls that offer some privacy, and there are skylights to bring light. it doesn’t mean that we build something or cook something, but we adjust things so that they can be appreciated. that is the most important thing about our architecture.

we are a kind of symbiosis of many life forms, and we try to put ourselves into clean environments where we can survive. we are always fighting against bacteria coming into the body, so the white cells are always fighting back. but when we put ourselves into 100% clean spaces, like a surgery room, many things can go wrong and cause allergic reactions.

recently, we designed a hospital but we made it open to nature. usually, people think that this would mean there is more bacteria, which would be bad for patients. however, we found that it actually works better for humans. we are not supposed to be in a controlled environment. we ski in the winter at -20 celsius, and in summer we go to the beach and it is hot. but we feel comfortable. so comfort is not about the degree, or the temperature, or the amount of moisture, it’s about the lifestyle. so we design everything for lifestyle, we make everything a part of nature.

the circular kindergarten was completed in 2007

image by katsuhisa kida/fototeca courtesy of tezuka architects

DB: you have completed many impressive timber projects. can you talk about the challenges and benefits of using that material?

TT: the great thing about timber is that you can keep the continuation from the structure to the small details. of course there are some great japanese architects making things with concrete, but I am not the person to fight against comfort — my architecture is not the fighting type. architecture is about fun, and how we can enjoy life. timber is quite a useful and capable material for this. for example, you can change timber. it can be adjusted on site with a carpenter, but when you do a steel structure, you have to plan everything ahead because most of the products are made in factories. concrete is the same. once you cast it, it is very hard to change it. often kids touch timber, as they feel it is natural, but they don’t do this with concrete.

it is also easy to control the cost of timber. we have a great collaborator who manufactures our projects. they do everything in 3D, and then they make a 100% perfect cut. so it comes on site, and it is joined together. we know the exact price, so we don’t need to worry about it.

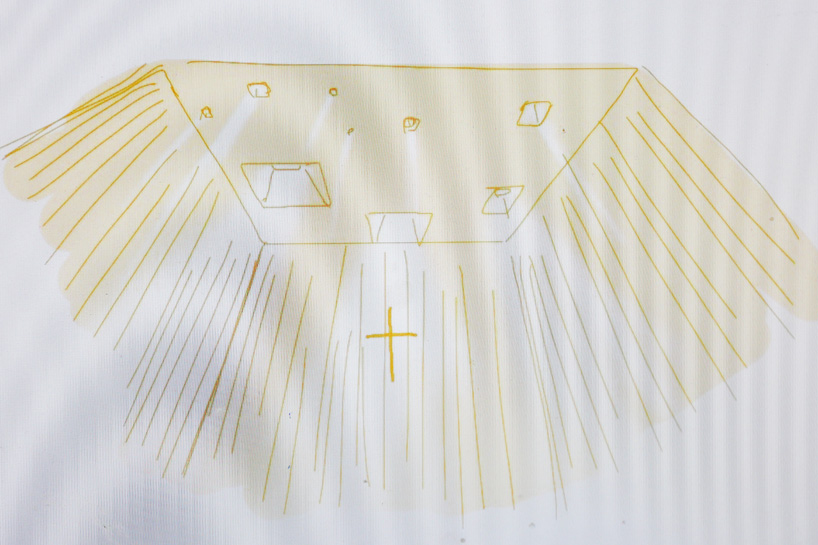

model of the bancho church

image © designboom

DB: the ‘home-for-all’ initiative by toyo ito has been important in the wake of the 2011 earthquake. what is your opinion of architects involving themselves with humanitarian projects?

TT: we have done two similar projects, and one more is completing now. the projects are paid for by UNICEF and the government and we understand that it is very important. it is what makes us japanese — we help each other because we are a small island. however, it doesn’t mean that we agree on every concept. I had a talk with mr. toyo ito, who I respect a lot. I know if he was not in this world, we wouldn’t be here, because he helped us to do our first project publication, and he wrote a recommendation for my wife to go to london. also our children are taking his class at his school. so he knows everything about my family! after the tsunami he tried to make everything for everybody, but I don’t think that is right. he said that he made mistakes before the tsunami, but I told him that he should never say that — he never made mistakes.

takaharu tezuka’s sketch of the bancho church

takaharu tezuka’s sketch of the bancho church

image © designboom

TT (continued): for example, he designed the sendai mediatheque. our kids like it, and many people love it, but it doesn’t mean that everybody loves it. I always say ‘home for everybody’ is not for everybody, ‘park for everybody’ is not for everybody, and ‘architecture for everybody’ is not for everybody. when you design something for a specific purpose, that has some kind of will of what architecture can offer — people can hold on to that kind of will. architects are the only kind of people capable of putting this kind of wish into architecture, and that kind of potential makes people happy.

most of toyo ito’s projects have this kind of potential, so I told him: never say you made mistakes. if you say ‘wrong’, people may misunderstand, and after the tsunami many people started denying the design of architecture. instead people are designing a square box, or just normal architecture. I think this decision is wrong. I think now is time to go back to how we were supposed to design. architecture should be for somebody, then it can be for everybody in the future. after the tsunami, people tried to design architecture for temporary purposes, for the short term. I think this is wrong. it is supposed to take time — sometimes more than 100 years — to understand its value. architecture is not for the now, it is for the future. to do that, you have to have a specific purpose.

‘roof house’ was presented as part of the japanese house exhibition at rome’s MAXXI museum

image © designboom

DB: now that computer generated visualizations are so commonplace, do you still use physical scale models or sketch designs by hand?

TT: in the 20th century, we used to think that computers or machines would be the future. these things represented our future. if you look at movies like ‘metropolis’, machines are the future, and if you look at ‘tron’, then computers are the future. but if you look at ‘the matrix’, which came to japan at the beginning of this century, the things going on the computer could be more real than the real world. already more than 15 years have passed since that movie came out, and I think that virtual reality is becoming more and more integrated into life. there is no boundary between virtual reality and reality. I make watercolor paintings on my iPad, that is a computer. so for me, there is no boundary between drawing on the computer and hand-drawing. I can do hand-drawing on the iPad, and I can do 3D visuals. everything is blurred and mixed.

‘roof house’ was completed in 2001

image © katsuhisa kida / courtesy of fondazione MAXXI

DB: outside of architecture, what are you currently interested in and how is it influencing your designs?

TT: I spend a lot of time with my piano. I used to play quite a lot, but when I was 11 I stopped, as my mother didn’t want me to become a musician. about 5 years ago, I started lessons again, and I realized that I can still play quite well. I admire just one composer, chopin, and nothing beyond him. since I was young I was always thinking: how can I make things like chopin? in music maybe it is possible, but in architecture it is so difficult. it is so difficult to make architecture perfect. architecture is nothing more than an instrument, and we can compose a life. and that is exactly what is happening in the fuji kindergarten. for example, just after its completion, chopin’s ’fantaisie-impromptu’ was in playing my head. I am a very good cook too, but maybe I’m a better musician!

DB: many of the recent pritzker laureates have been japanese. how do you assess the current state of japanese architecture?

TT: it was very good that I grew up in a society where architects had the opportunity to win the pritzker prize. you know, my wife always wears red, and I always wear blue, so when my daughter was five years old, kazuyo sejima said: ‘I’m sorry that your daughter is always in yellow, I am going to buy a black shiny dress for her with flowers!’. I remember that, and we still see kazuyo sejima. shigeru ban is quite a frank person, and I also talk to him. these people are very close, especially toyo ito. for us, pritzker prize winners are not something ‘beyond the crowd’. the great architects are always very close to the people. they are frank, and they are quite easygoing. it is not easy to become a pritzker prize winner, but it is quite possible to learn from them. that is the great thing about being in japan.

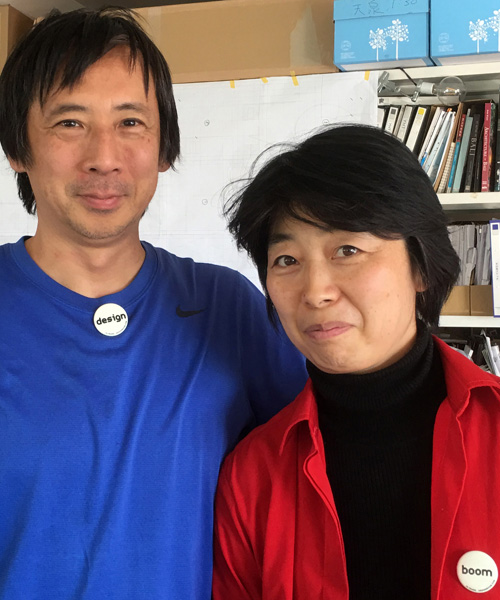

portrait of takaharu and yui tezuka

portrait of takaharu and yui tezuka

image © designboom

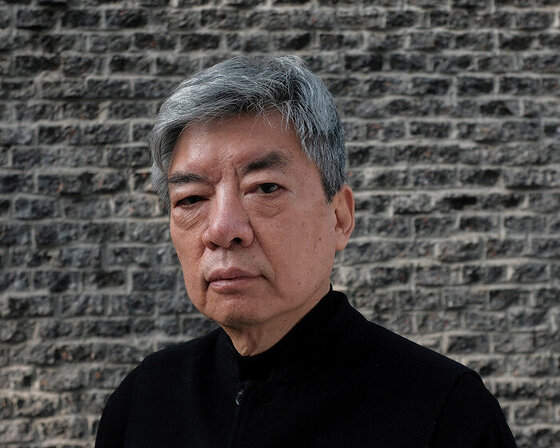

DB: which architects or designers working today do you most admire?

TT: in japan, toyo ito. he is not just making architecture, he is making the world, and society. he is raising the next generation. I think making architecture is possible for everybody, but raising the next generation is a much harder task. after he won the pritzker prize he is doing even more. he is a great person, and I am not just talking about his architecture. of course, I respect richard rogers as well.

DB: what is the best advice you have received, and what advice would you give to young architects and designers?

TT: be yourself, that is the most important thing. each person is unique, and usually the world wants something unique. if you want to be an architect it is very important to be unique, but it doesn’t mean you have to do something stupid. being yourself is the most natural way to be original.

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save