KEEP UP WITH OUR DAILY AND WEEKLY NEWSLETTERS

PRODUCT LIBRARY

do you have a vision for adaptive reuse that stands apart from the rest? enter the Revive on Fiverr competition and showcase your innovative design skills by january 13.

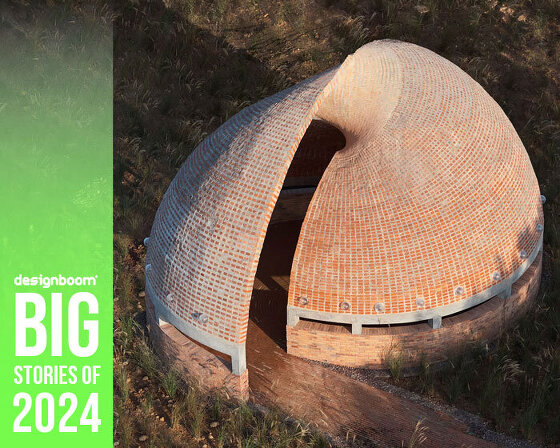

we continue our yearly roundup with our top 10 picks of public spaces, including diverse projects submitted by our readers.

frida escobedo designs the museum's new wing with a limestone facade and a 'celosía' latticework opening onto central park.

in an interview with designboom, the italian architect discusses the redesigned spaces in the building.