richard meier & partners architects interview

reynolds logan and bernhard karpf, associate partners of richard meier & partners

portrait © designboom

—

designboom met with reynolds logan and bernhard karpf, associate partners of richard meier & partners at the international firm’s new york offices on may 22, 2013.

—

reynolds logan (RL)

bernhard karpf (BK)

what is the best moment of the day?

BK: that’s tough. I don’t know, because there is no best moment of the day.

RL: there are some favorite moments of the day for me. the quiet in the morning when you just get up and take the first sip of coffee and look forward to the day, is pretty good. and maybe to book end that at the other side, I find those last few moments (before you throw yourself to sleep), is when I reflect on what happened, or what I got accomplished, and then ask what’s happening tomorrow? what might I have done differently? what did I learn? what were the rich moments of the day that didn’t have anything to do with learning? maybe I would say the evening wind-down. lunch is pretty good too.

BK: the funny thing is sometimes there’s a day where maybe mid way it’s like, this is cool–something happened that you really enjoyed. unlike my colleague, yes, I can enjoy the morning too, or I can enjoy the evening, but it’s kind of predictable. the good moments of the day are when things happen, when you get a surprising phone call or you finally have this idea on a project you have been working on for the longest time and you never could figure out how to turn that corner, and suddenly it plops into place, and it’s like, ‘oh man, this is good!’. I like those moments–they’re unpredictable.

jesolo lido condominium, italy

photo © roland halbe

see designboom’s original articles on the construction phase and completion

what kind of music do you listen to at the moment?

BK: I’m in the plane a lot, flying to europe; frequently with lufthansa, and they have something called channel 15 world music. tunes from mali, mumbai, former yugoslavia–from all places in the world. I think it’s produced somewhere in berlin. I like that.

RL: that sounds pretty good, like the emerging markets of music. I won’t listen to the radio anymore because I don’t want to listen to all the talking and the commercials. so, I will go to pandora, and I’ll program something. like lately, maybe it’s a crazy phase, it’s chamber music. I find it very relaxing and calming. it lets me basically shut out the world and think.

do you listen to the radio?

BK: I’m listening to the radio, whatever the radio offers. there are good stations here in new york.

RL: I used to listen to the radio when I was much younger, and I got all this fresh music coming at me. and now, the world is changing so fast and there’s so much media thrown at you, that I’m the opposite.

jesolo lido condominium, italy

photo © roland halbe

what books do you have on your bedside table?

BK: I actually have two. one is an interesting book by a french author. I got it in a little used bookstore, and it’s about how the meter was invented and the story behind it. it discusses the french revolution and how they were trying to generalize measurements that were all over the place. so that one’s for brain reading. for entertainment, what was it again? let me think for a moment. it’s the latest john erdman novel, but I really haven’t touched that in a while (it’s still sitting there on my bedside table), so the title beats me.

RL: I also have two, and maybe they’re perfectly predictable. one is the robert hughes book on barcelona that’s probably 10 years old. time flies, maybe it’s older than that, but my wife makes fun of me because I can’t get all the way through it. it’s a bit of a slug, but it’s really really interesting, however you can get bogged down in the history, so I tend to read just a little bit of it at a time. the other is the biography of le corbusier. I feel more obligated to read that than enjoy it, so that’s also a little bit at a time.

do you read architecture magazines?

RL: yes.

BK: sure do. have to. more a combination of reading and flipping through. whether it’s architectural record, or architect; or any number of these european magazines that are fantastic that richard receives, but I’m not sure he’s the one who really looks at them. el croquis from spain–always looking through those. every once-in-a-while you get interested in professional service articles in architectural record or another publication, but it’s primarily a visual activity.

jesolo lido condominium, italy

photo © roland halbe

where do you get news from?

BK: very easy. the newspaper. I think I’m the last one here in the office who actually reads the newspaper the old-fashioned way. so that’s the source. no TV. maybe a little bit of radio, but newspaper.

RL: I concur. I think the new york times is the best newspaper on the planet. and um, he (bernie) reads the real thing, and I read it on my iPhone. you don’t get ink on your fingers that way.

BK: that’s true.

RL: or your face.

BK: but you can wrap some fish in it at the end of the day!

RL: that’s right.

BK: or use it for something else…

and architecture news you get from magazines?

BK: no, actually most of the stuff these days you get online. you’re subscribing to a number of these services and you get your daily update on whatever you’re interested in. I guess you know how that works better than we do. but, I mean we have these things pop into our inbox and you just flip through and see if anything new happened–competition winners announced, new projects launched, that kind of stuff, but it’s all online. I think for some reason, the magazines are no longer the source of news. they are more a record of what has happened, because you read about certain things in a printed publication about a month or two later, and then you say, ‘oh, that’s kind of old.’ right? current news comes from online sources.

city green court, prague, czech republic

image © roland halbe

see designboom’s original article here

do you have any pets?

BK: nope.

RL: I have a two-year old son. that’s as close as I get. he’s enough trouble without more pets.

city green court, prague, czech republic

image © roland halbe

when you were a child, did you want to become an architect?

BK: nope. my plan was to become the next einstein, a scientist actually…

RL: really?

BK: a space explorer, yeah.

RL: I like that. you learn something new every day about your colleagues.

I don’t remember what I wanted to do as a child. maybe a little of everything, but I got interested in architecture at maybe 15 or 16. and I shouldn’t say this, but I have this idea that I’m like most people, that you go through life and if you’re lucky, through your life’s experiences and teachers, you stumble upon something that you become very interested in. I was interested in drawing in high school, and I had a teacher who encouraged that and got me into–at the time it was referred to as–mechanical drawing. he introduced me to a couple of architects because I was curious in drawing plans of things. one thing led to another, but I don’t know if any of this would’ve happened if I hadn’t had this special interest of one particular teacher, and the gift of encouragement. I don’t really think that I’m so different than any other successful professional in that way somehow.

bodrum houses in yalikavak, turkey

image courtesy of richard meier & partners architects

see designboom’s original article here

where do you work on your designs and projects?

BK: it happens everywhere. I mean again, it’s not you sitting down and it’s there. it’s not like you just draw a project. it’s a process developing ideas. you can’t really confine that to a particular space or time. sometimes you get funny ideas late at night. it can happen in an airplane, it can happen in a bar, it can happen in the care while driving somewhere…

RL: for me sometimes it happens in a dream. I think even in the earlier days of my youth, maybe even when there was much more design intensive activity, I used to keep a little piece of paper by the bed because if you wake up at 4 o’clock in the morning and you solve that problem that you have been working on for months, it’s a pity if you don’t write it down, because sometimes you just don’t remember what that idea was.

BK: because the next dream is even better. I think a study is basically like a marketplace and production place. we come here and just take the ideas and share them with each other and turn them into real projects you know as a process, a narrative process. and the other thing you have to do is document it in drawings in models. but, the ideas can happen all the time.

do you discuss your work with other architects?

BK: on occasion. I mean obviously when we work, as we’re working worldwide, we typically collaborate with local architects. and so, when we start a project, we have this conversation with them on what the project should be, what are the parameters for the project requirements, and any local issues we need to address with the project.

bodrum houses in yalikavak, turkey

image courtesy of richard meier & partners architects

describe your style, like a good friend of yours would describe it.

BK: oh, that’s a hard one. I mean number one, we are working in an office that already has a very established, formal vocabulary. so, I think we’re all okay with that, and we’re pushing that in 12 different directions, because issues change. we’re looking at things, in regards to sustainability, with a much closer eye. we’re looking at materials, and those materials we’re looking at are things that we didn’t look at before. the projects got bigger faster, they’re more international, so style is a difficult one. I mean, if it comes down to how we work, I want to call it, ideally somewhat organized. if that’s a style, you know just as a process. understand architecture is a very long process. even design is a long process, so you don’t have to solve everything the first day. you take your time, repeat and repeat, and see what comes up. be curious about what comes up.

RL: I would say the language for all of the work here is very similar. the products can be superficially similar, but underneath, they’re all a little bit different. overall, obviously, looking at the work we’re interested in a certain rationality and order to the design. we are interested in lightness and transparency, and the use of a fairly simple palette of modern materials. we’re not one to go experimenting with a lot of new and different materials on every project. however, underneath that superficial resemblance among all these projects with their language is, that everyone is different in terms of its approach to the site. everyone is specifically tailored to its program. these are things that make projects different. then, if you get underneath the surface and you really look at them, you can see the different response to every project and to those factors.

italcementi i.lab, italy

image © scott frances

see designboom’s original article here

please describe an evolution in your work, from your first projects to the present day.

RL: well as bernie mentioned, maybe the most important thing is sustainability. we have been working in europe the whole time we’ve been here, 25 years. and what’s different, and was always different about working in europe, was that there are very clear regulations about light, ventilation, and energy because the cost of energy there is much higher than it is here. so, we were always interested in building systems that made sense. long before it was fashionable, and obviously in the last 10 years, it has become much more critical that we actually do seriously worry about our use of the world’s natural resources. they’re limited. there are more people on the planet every day using more and more. we have to do something about that. I think that, in the whole time that we’ve been in new york, it’s become much more a part of our consciousness–long before LEED and long before it became fashionable to talk about sustainability–to promote your work. it’s in our blood.

BK: I can remember in our early days, maybe 25 years ago, 20 years ago, we developed relationships with very good building engineers who saw this issue coming, who were more global in their practice and understood these same energy issues that we did, I think maybe even more than our level of consciousness. they were pushing us. particularly our friends over at ARUP and partners.

italcementi i.lab, italy

image © scott frances

what project has given you the most satisfaction?

RL: everybody has their favorite. what’s bern’s?

BK: I have to answer that differently. it’s not a project necessarily, but what I notice is, and it gets worse with computers because you can simulate everything up front… what is always good is when you start out designing, you try to imagine something, and the better you are at putting it on paper and working out all the corners, all the details and this and that, and you see construction going up, that is always a very satisfying moment. and then the project is done, and it’s like okay. it’s like a ‘so what’ moment. I mean, it’s not a surprise anymore because you have been spending the last two years of your life on this project. and then, when you see it done, it’s like okay, yeah, this is the way it should’ve been. this is the way it is. you know, this is the way I thought of it. you know, it’s not all really a surprise. we used to have a game in the office because there are corners in a building or situations in a building that cannot really be properly resolved. we call them the bandaid corners. for a while we had a competition that before the thing was going into a construction, we picked the worst corner and then the most surprising corner. everyone on the team could basically vote for a corner and say, ‘this is a corner that’s going to be really ugly’, or some would say, ‘no, this corner despite the fact that it will be ugly, is going to be surprisingly elegant. we’ll find out’. and there are those moments and it’s true. sometimes you look at things and you thought it will never work. it doesn’t go around the corner, it doesn’t do what it’s supposed to do. and then, turns out it’s actually pretty good. if I had to pick a project I would say a small museum in baden bahn in germany years ago, and that was small. it was a good environment, a good client. it turned out to be a really nice project and has been embraced by the local population to a degree that we did not imagine when we started out on it.

italcementi i.lab, italy

image © scott frances

who would you like to design something for?

BK: well, I would like to design a soccer stadium. we’re trying. can you publish that on designboom? ‘richard meier + partners would love to do a soccer stadium’. that comes from me obviously because I love soccer. I used to play and go to the stadiums when I have time. I can’t really do it here in new york. there’s not much going on, but when I’m in europe and I have a weekend over there, I go to the local soccer palace or stadium. in some ways we’ve been trying to get into this world cup business. when they pick the sites for the next world cup, and by the time we get around to it, we find out it’s already taken care of. someone else did it already. so we’ll have to see if we can do something about that. if you know someone, give them my number.

RL: I’m still interested in museums. I almost feel embarrassed to suggest that partly because we’ve done so many. but the other reason is because at the end of the day there are so many interesting kinds of projects out there. some that we’ve done before and some never done before, and they’re all new. I think we’re always appreciating a new experience no matter what it is. the most important thing to us is the people who are doing work with us–the client, the engineers, everybody around that thing–and that they are interested in doing something good that we’ll be very proud of after. it’s not simply a service that we’re providing and trying to do the best we can. it’s a project where everybody has the same vision and dream as opposed to just, ‘ok, we do it the best we can’ and hope everybody likes it after.

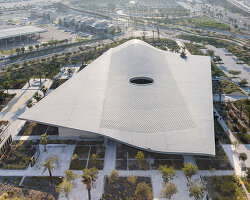

OCT shenzhen clubhouse, china

photo © roland halbe

see designboom’s original article here

is there any designer and/or architect from the past, you appreciate a lot?

RL: well you probably won’t be surprised to hear the two of us say that we’ll always be referring to the modern masters like le corbusier, and frank lloyd wright, mies van der rohe, alvar aalto, louis kahn. seems like every time you try to do something, you wind up flipping through pages of their work in the library because the architecture is so solidly forever. it’s that good. I think that’s something that we aspire to as well. what all of these people share is a kind of sensibility about simplicity and order that’s born out of, as I mentioned earlier, the site and the program, and a certain level of maybe personal expression in there, but it’s orderly.

BK: one that I want to add, but he’s not up there on the hall of fame with the upper tiers is carlo scarpa. probably one of the favorite architects when it comes to dealing with materials and details and even working in a small environment. it doesn’t always have to be big. it can be very small and just right.

OCT shenzhen clubhouse, china

photo © roland halbe

and those still working / contemporary?

RL: for me there are too many. I like so many things that are going on out there that I don’t want to single any one out.

BK: I think I could go away from the architect, and voice my interest in those that don’t really have a name, those people that build infrastructure. you know the guys who do the bridges? I mean sometimes, you see a bridge and say ‘man, this is pretty amazing’. here in new york, sometimes you walk through subway stations and you say ‘wow, this is pretty good’. we know there are people out there that still do that today, build subway stations and whatever. I have total respect for them.

HH resort and spa, korea

image © vize

see designboom’s original article here

designboom asks richard meier & partners’ associates bernhard karpf and reynolds logan:

what advice would you give to the young?

video © designboom

what advice would you give to the young?

BK: be stubborn, and follow your ideas. simple as that. you know, if you want do it, it’s a long haul. it’s not something… an architect is not, it’s not like a… going back to soccer, a soccer star. it’s like 10 or 15 years and it’s either talent or is not. architecture, I think, requires talent, but it needs a lot a lot of work to get experience. I was always surprised that when you open magazines that talk about young architects, it turns out that they’re like 50 or 60 years old. they’re still young architects ’cause obviously, it takes a long time not only to build a building, but also to learn how to build a building. so you really gotta be stubborn and you got to follow that idea that you wanna be an architect.

RL: I would say two things. one is to travel and see things, experience them. it’s too easy to be seduced by photographs in magazines and books, and not really appreciate the quality of what something really is that’s really 10x more meaningful going there. and the other is to, in another way about avoiding superficiality, I think architecture is more than just making images. I think we provide a service to people that’s terribly important. it’s about shelter, and making environments, and making environments that work. so, I would suggest that everyone, all young architects, not be seduced by the instant gratification of making things too quickly. there’s a process of learning–what it takes to make a building–and I don’t think it’s any less important than the design of the building itself.

HH resort and spa, korea

image © vize

what are you afraid of regarding the future?

BK: the future is glamorous and happy. no. it’s not happy. but you know, if we were afraid of the future, we’d be in the wrong profession. we probably should be driving the subway or something other. but architects, we’re embracing the future, I think. most of us do. this is what makes it exciting. I mean, you look at new york here, look out the window here. you see all these buildings that went up over time and the thing is the people who put these buildings you know, whether they’re clients or architects or engineers or whatever, they built in maybe to a degree for themselves, but to a more major degree, they built it for the city they live in in order to build in the city, you’ve gotta believe that the city is the future. that the city has a future.

RL: I wouldn’t say afraid. so many things about the future that you can’t predict. I’m optimistic about it. like you, I look forward to it. I do worry about a couple of things, and the thing that comes to my mind right away is that maybe it goes back to a thing I mentioned earlier, and that is the barrage of media and electronic information that just seems like everything is instantly available to you these days, and there’s not enough. everything is moving faster, and I don’t think that’s a good thing. I think that the faster things go, the faster they change, and the less meaning they have. some of the things you do have, the expectations that surround it and I dont’ know, from our perspective here I think that we want to make really good important buildings and I hope that’s what most architects want to do, but it takes a while to design a good building. it takes a while to build it. and what I’m afraid of is that everything is happening at magnum speed these days, as is the perception of what’s happening, and so superficial preferences and styles are changing in that way that… I’d just like things to slow down a bit.

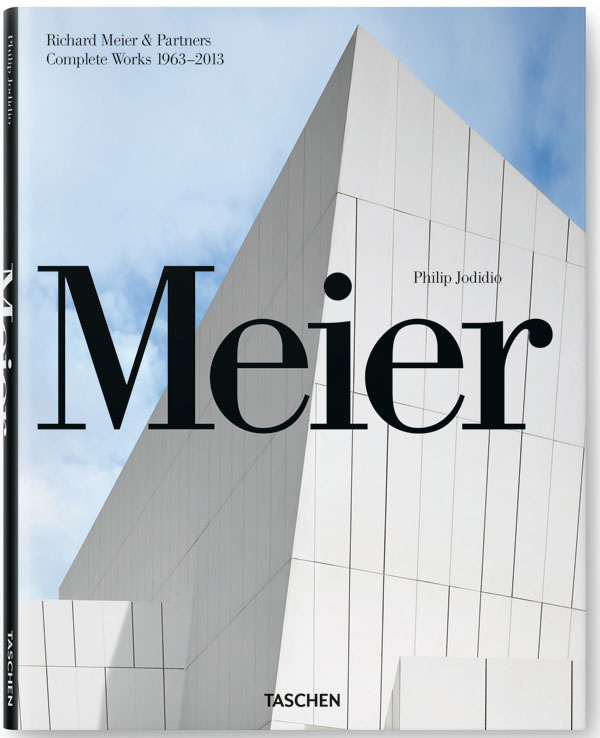

richard meier & partners: complete works 1963-2013

to celebrate the firm’s 50th anniversary, TASCHEN has published a monograph richard meier & partners: complete works 1963-2013. the book offers an extensive survey of the international practice’s major achievements, covering the entirety of the american architect’s career.

—

richard meier, managing partner

richard meier was born in newark, new jersey in 1934.

he received his architectural education at cornell university, and has been awarded honorary degrees from the university of naples, new jersey institute of technology, the new school for social research, pratt institute and the university of bucharest. he founded his own practice in new york in 1963, after a brief stint at skidmore, owings and merrill. since then he has been awarded major commissions in the united states and europe which include courthouses, city halls, museums, corporate headquarters, housing and private residences. some of his most recognized projects include the getty center in los angeles, the high museum in atlanta, the frankfurt museum for decorative arts in germany, the canal plus television contemporary art, the hartford seminary in connecticut, and the atheneum in new harmony, indiana. in 1982, richard meier was awarded the pritzker prize for architecture, considered the field’s highest honor, and at the time was the youngest recipient in history of the prize.

bernhard karpf, associate partner

bernhard karpf joined richard meier & partners in 1988, and was named an associate partner in 2011. he studied architecture and literature at the university of stuttgart, germany, the ETH zürich, switzerland, and the technical university darmstadt, germany where he received his diploma. after being awarded a deutscher akademischer austauschdienst fellowship in 1986, he continued his education and received a masters of architecture degree at the urban design studio at cornell university in 1988.

reynolds logan, associate partner

reynolds logan joined richard meier & parners in 1988, and has been an associate partner at the firm since 1996. he received his master’s of architecture from clemson university after studying and traveling with the charles e. daniel center in genoa, italy. he also earned a BS design magna cum laude from clemson university.

happening now! in an exclusive interview with designbooom, CMP design studio reveals the backstory of woven chair griante — a collection that celebrates twenty years of Pedrali’s establishment of its wooden division.