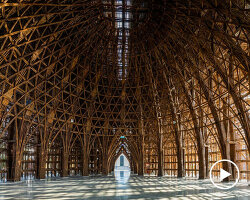

studio zhu pei, jingdezhen imperial kiln museum, jingdezhen, jiangxi, china, 2016–2020 | image © schran image

KEEP UP WITH OUR DAILY AND WEEKLY NEWSLETTERS

happening now! thomas haarmann expands the curatio space at maison&objet 2026, presenting a unique showcase of collectible design.

watch a new film capturing a portrait of the studio through photographs, drawings, and present day life inside barcelona's former cement factory.

designboom visits les caryatides in guyancourt to explore the iconic building in person and unveil its beauty and peculiarities.

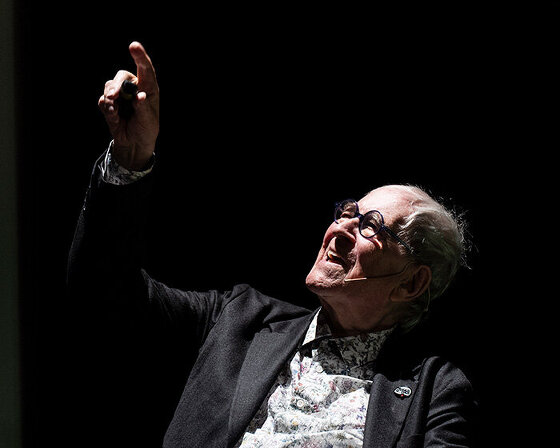

the legendary architect and co-founder of archigram speaks with designboom at mugak/2025 on utopia, drawing, and the lasting impact of his visionary works.

connections: +330

a continuation of the existing rock formations, the hotel is articulated as a series of stepped horizontal planes, courtyards, and gardens.