designboom interviews michael murphy, co-founder of MASS design group

michael murphy, co-founder of MASS design group

portrait © designboom

designboom is a media partner of the annual WHAT DESIGN CAN DO! (WDCD) conference in amsterdam. each year, WDCD invites a line-up of international speakers, across diverse creative disciplines, to tackle a number of key questions which contemporary society is trying to respond to. the 2015 edition saw the themes of humanity, cultural consciousness, urban issues and the senses being addressed. creatives from across the globe stood in front of a packed audience at the city’s historic municipal theatre stadsschouwburg, to discuss their role as designers or architects.

michael murphy, co-founder of MASS design group, was invited to contribute to the issue of humanity, and communicate architecture’s part in responding to the social and economic challenges of our world today. the boston-based practice was founded by murphy and alan ricks in 2008, and has since been using architecture to positively impact communities across three continents, improving people’s lives by delivering dignity, good health care and well-being to individuals. designboom sat down with michael murphy to discuss what has influenced his role as an architect, media’s impact on architecture and which project has given him the most satisfaction to date.

michael murphy on what originally made him want to become an architect

video © designboom

designboom: what originally made you want to go into the field of architecture?

michael murphy: I was originally influenced to go into architecture for a couple of reasons. the primary one was that I lived in south africa when I was studying in college, and saw the transition of a post-apartheid government on the landscape and the urban condition in cape town. it was quite dramatic to watch razor wire and electric fences go up and enclose a kind of political and social dimension behind the real estate; and the political dimensions really play out around the built environment. I found that really striking — the social and political implications of buildings, and how they represent the conditions of the state. that was one of the reasons why I was very interested in design and urbanism, and becoming an architect.

DB: what particular aspects of your background and upbringing have influenced your approach to design and architecture?

MM: the primary thing behind my background which has influenced my approach to architecture is probably a very personal story about working on my house with my father actually. he was suffering from cancer and in order to cope with the treatment we worked on restoring our old arts and crafts home together. I remember him walking outside and saying how that exercise had really saved his life, and it was this very restorative process of the day-to-day activity of working on building and restoring and maintaining one’s home. and, I was really convinced then that our buildings directly affect and improve or change or impact our health and our lives, and for that reason I really wanted to become an architect and build buildings that improve lives and improve health and focus on the relationship between our well-being and our built world.

butaro hospital in butaro, rwanda

image © iwan baan

the various programs of the hospital are connected through outdoor ‘hallways’

image © iwan baan

DB: to date, what has been the single biggest influence on your work as an architect?

MM: the single biggest influence is probably dr. paul farmer who is an amazing medical professional and hero to many. he’s really shown me a new way to think about the role of the built environment, the role of buildings and impacting people’s lives. he’s introduced me to amazing thinkers like johan galtung, a philosopher of peace studies who thinks about such terms as structural violence, and how our world can keep people from achieving their full potential. I often think about those thinkers when we imagine what else architecture can do, because it’s when it keeps people from achieving their potential, that architecture really participates in a negative impact, or what some might call structural violence. so, I’ve been influenced by them. I think in terms of architects I’ve been very influenced by some of the southwest architects in the US like rick joy and will bruder. I find marlon blackwell’s work absolutely, totally inspiring. I am influenced by architects from the modern era, giancarlo de carlo of team 10, and italian late modernists like that. we’ll go back to william morris as an arts and crafts architect and his political bend. francis kéré is a big influence of mine and friend, and others like that.

the hospital wards are arranged so that the beds all have views of the surrounding landscape

image © iwan baan

the butaro hospital at dusk

image © jay cody

butaro doctors’ housing in butaro, rwanda

image © iwan baan

see more about this project on designboom here

DB: when you started out, was your intention to have a firm that focused on social, non-profit work, or did you have a different idea in mind?

MM: my firm has always been a non-profit, but I don’t really see the distinction between a social architecture and a non-social architecture. I wonder what would be a non-social architecture? it would be one that doesn’t really exist or is just ephemeral. I am interested in buildings and implementing buildings and building buildings, and seeing how they impact people’s lives; and all buildings impact people’s lives — some intentionally and some unintentionally. so, I was interested in purpose-built structures and intentionality in the built world, and because of that, obviously deeply cared about the social and political implications of the built world. I think all architecture is political of course. all architecture is social, we just sometimes don’t elevate the conversation about where architecture is becoming incredibly social or political, and we must just add that to our repertoire of evaluation.

DB: you must be working alongside a lot of medical workers and people who are very familiar with the types of diseases that you are trying to keep under control in the buildings that you’re designing. how does that collaboration evolve? you are thinking in different ways, but ultimately have the same goals. could you elaborate a bit on the design process?

MM: our design process is very integrated with the medical professionals that we work with. I mean, they know what we don’t and inform us of what we need to be looking for. around airborne disease like tuberculosis, we’re very influenced by a medical doctor at the harvard medical school called ed nardell. he is a pulmonologist and he came up to us and explained early on in the project what the role is of these terrible waiting areas and how the lack of design is causing disease to transfer. we worked very closely with him to develop a strategy in order to use his rules of thumb and design towards that outcome based method, and that’s been in our minds, a very successful collaboration. with this new project around diarrheal disease and cholera, we’re working with this amazing doctor in port-au-prince one of the leading researchers of HIV, and one of the leading doctors in the caribbean. he’s on the cornell weill faculty, his name is dr. bill pop. he’s an amazing visionary leader and he’s really shown us not just how to treat disease, but the bigger socio-economic implications of treating disease and really what a public health strategy is about — that a building is one component of that larger strategy, but the strategy needs to be there in order for the building to be successful.

the dwellings are a series of streamlined volumes

image © iwan baan

interior view of one of the houses

image © iwan baan

view of the hillside site of the butaro doctors’ housing quarters

image © iwan baan

DB: what would you say MASS design group’s strength is, and how have you honed that skill over the years?

MM: I think one of the strengths that we, well at least we aspire to achieve and work towards, is making sure that every building that we work on has a very simple, singular idea. I call this a mission of a building, that it seeks to achieve through its tectonics, through its identity, to the way its built — a singular, simplified concept. simplicity is what’s so necessary I think to me in architecture in order for us to transcend the building itself and be something more than just a building, but actually be part of a movement. so, we try to really focus our work both in the materials we choose, the way in which we build and the forms that we make, to achieve the highest level of simplicity and singularity to achieve maximum impact.

DB: today, computer generated drawings are very commonplace, so I am wondering what your view is on the role of the physical model, and hand drawing.

MM: we use all tools at our disposal in order to create architecture. sometimes we’re in the field drawing by hand in the dirt because people don’t know how to read drawings, don’t know how to read a plan or a sectio4n, so if you give them a booklet it means nothing, it’s a whole other language. so there, 3D modelling, axonometric drawing, simple sketching could be much more effective than a construction document. on the other hand, our work is hyper customized, especially our recent work in haiti, and so that could only have been developed through parametric modelling, robotic fabrication technology and software. and, we leveraged that way of working and that software in order to maximize the amount of labour we used on the ground, instead of maximizing the amount of robotic cuts we could make. so, we’re using these technologies in a way to affect change, but we’re using whatever we can at our disposal.

michael murphy on the role of media in architecture

video © designboom

DB: what is the role of media on architecture?

MM: I don’t know if I can respond to media on architecture, but I certainly can respond to communication in architecture which I think is incredibly important. it’s very important for the architectural profession to articulate their ideas to the public, and it’s something that I think we do poorly. often, so few architects are really known, so few architects are actually working, and yet there are so many buildings out there, and there’s so much work going on that it seems as though we have a messaging problem where we’re unable to articulate why we’re valuable, why the public needs our work, what value we bring to the public. and, in the worst case scenario architects are considered frivolous and unnecessary and icing on a cake, as opposed to a profession which I deeply believe is fully immersed in trying to create a better world, trying to create better cities, trying to create purpose built buildings, institutions, hospitals that help and serve society and serve communities. I think most architects are committed to these principles, and yet we often get considered as sculptors or frivolous excess, instead of core fundamental advocates for a better world.

umubano primary school in kigali, rwanda

image © iwan baan

see more about this project on designboom here

DB: outside of architecture, what is fueling your work?

MM: a lot of different fields are influencing our work, certainly the advances in health care influence our work, both in terms of policy change and significant public health changes. I’m very fascinated in the big public health disasters we’re seeing now that are specifically related to urbanism. cholera for example was directly related to how our cities are capable of coping with water and sanitation, and how the lack of design is causing public health nightmares. ebola is related to a lack of available space — hospital spaces, medical spaces — that people want to use. so we’re very interested in seeing what the spatial dimensions are of big issues that we’re dealing with as a society. I mentioned johan galtung. I am very influenced by thinking about advocates for peace or social change, more specifically behaviour change or behavioural science; and how there are real significant shifts happening in the way people understand human behaviour and how a particular space can nudge and improve, or fault and disrupt behaviour. I am particularly fascinated by that. and then, I am very interested in activists who are out there trying to solve problems — significant social problems or political problems — through structural change. bryan stevenson, from the equal justice institute, comes to mind. he’s doing amazing work around really remapping the united states, its history of slavery and lynching an imprisoned population as a history of slavery is now the US prison population. his work, while it’s largely about legal activism, also has significant spatial implications if it were, to be realized in its full potential. these are the kinds of people we want to work with, and see how architecture makes a difference in their work.

DB: who from the past do you admire or look to as an influence?

MM: I have been very influenced by a number of professionals a number of architects who, especially in the modern era, late modernism who came out. team 10 architects were doing very fascinating things. paul rudolf is fascinating and I think has really taught me about building and how one designs a journey or an experience and the intimacy of our infrastructure. I mentioned william morris from the arts and crafts movement and how influential he’s been for us to think about: what’s the role of the craftsman, what’s the political role of the craftsman in the creation of better buildings, better design in designing our entire world. I was happy to see frei otto awarded the pritzker. the kind of expressiveness and urgent social issues that he was coping with or trying to cope I thought also have been compelling to us thinking about massive systems change. and then the other people I’m really fascinated by those who are struggling with hospital design. hospital design is really a challenging typology and it’s really a systems design problem and many of the architects that coped with that, especially in the 60s and 70s, being influenced by the metabolists or archigram and trying to deploy those as medical facilities we find is totally fascinating. sometimes misguided, but very interesting challenges of bigger, bigger issues that they’re starting to encounter in the design of new types of buildings.

the umubano school is built into a sloped site

image © iwan baan

view of one of the classrooms at the primary school

image courtesy of MASS design group

DB: what project to date has given you the most satisfaction?

MM: our inaugural project, the butaro hospital, certainly has paid many dividends and made us feel some level of validation that I did not expect. I did not expect that the project would be so well-received and we’ve been so touched by that. I think because it’s our first project, it’s also added additional value over time. we’re right now in the fourth phase of that building. we’ve built housing, we’ve built a cancer center on the site, we’re now building more housing and we’re about to design and build a new university on that campus. so, it’s become this continual project that has added brought forth more buildings and additional partners. there’s an amazing ongoing relationship with that initial project that has changed the way that I think about buildings all together. some of the new work that I’ve been really excited about is this project in haiti where we’re trying to deal with waterborne disease like cholera, and cope with designing a highly customized skin system with local metal workers which has just been incredibly powerful for us to realize. it’s a very challenging condition to build in port-au-prince, but incredibly satisfying to see it completed and being used. patients just entered it last week, so it’s very nice.

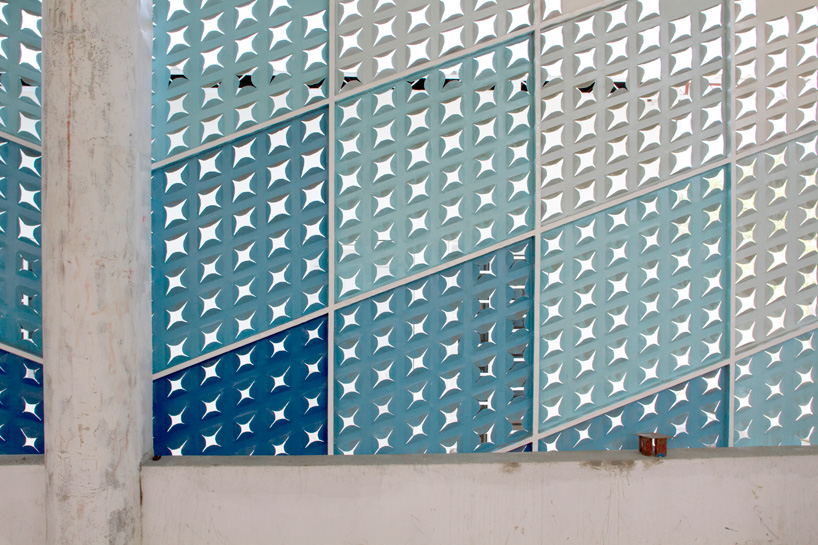

GHESKIO cholera treatment center in port-au-prince, haiti

image courtesy of MASS design group

see more about this project on designboom here

the center is meant to treat patients with cholera and other diarrheal diseases

image courtesy of MASS design group

detail of the perforated façade

image courtesy of MASS design group

DB: what is one of the best pieces of advice you have ever received?

MM: I think the two pieces of advice that stick out in my mind are stay focussed on a simple idea, and hone into that and stay rigorous and true to that; and then the second one is don’t wait for your turn and sort of take opportunities when they come towards you, and learn by doing in that process. we’ve learned a lot by just trying to do it and failing and getting up again and trying to figure it out again. that to me has been the most influential activity over the last 10 years doing this work.

DB: is there a particular motto that you live by?

the motto that we live by is that we like to think that design is never neutral — it either helps or it hurts. we must focus on design that helps, otherwise we’re making design that hurts — there’s no in between. there’s no middle ground. it’s one or the other.

WHAT DESIGN CAN DO! is an international platform about the power of design, promoting design as a catalyst of change and renewal and a way of addressing the societal questions of our time. formed in 2011 by a group of designers from various fields, it aims at showcasing best practices and visions, raising discussions and facilitating collaboration between disciplines, raising awareness among the public for the potential of creativity. at the same time, WHAT DESIGN CAN DO! calls on designers to take responsibility and consider how their work can impact the wider society.

happening now! in an exclusive interview with designbooom, CMP design studio reveals the backstory of woven chair griante — a collection that celebrates twenty years of Pedrali’s establishment of its wooden division.