manuel herz is a german architect who leads his own practice based in basel, switzerland and cologne, germany. his firm, manuel herz architects, has completed a variety of projects, including a jewish community center in mainz — a project that explored the contemporary significance of ancient jewish traditions. herz’ most recent project is a house with a striking façade comprising operable horizontal and vertical louvers, (illustrated in the video at the top of this page). besides his work as a practicing architect he researches and publishes on the relationship between architecture and nation building, and on refugee camps. appropriately, herz’ contribution to the 2016 venice architecture biennale considered the role and nature of such settlements in western sahara.

to learn more about the architect’s work and influences, journalist joana lazarova spoke with manuel herz who, among other topics, discussed his initial interest in architecture and his upcoming project in eastern senegal. read the interview in full below, and see designboom’s previous coverage of the architect’s work here.

portrait of manuel herz in basel, 2018

image © julien lanoo

joana lazarova (JL): you became well-known through your early works — legal / illegal in cologne and the synagogue mainz are some of your first defining projects. what led you to choose such a bold architectural language?

manuel herz (MH): a lot of it, of course, comes from a personal preference. I am interested in a certain kind of sculptural quality in architecture, which I have been and am still trying to explore. having said that, I think I was never trying to develop a formal language that is applied and reproduced in each project, in the same way a formal formula is repeated. what truly interests me is the spatial, political and social quality of architecture, and of course also the material and engineering side of it. but I’m certainly not interested in a formula.

jewish community centre, mainz, germany (2010) | read more about the project here

image © iwan baan

JL: when did you become interested in architecture?

MH: I don’t come from a family with an architectural background, but my parents were very interested in the arts and in architecture. their circle of friends was full of artists and architects. I think it was in my final years of school that I decided to study architecture, because at the time, I thought it was a brilliant combination of something theoretical and philosophical on the one hand, and something artistic but also very practical on the other hand. that’s what fascinated me in my youth, and it is what still fascinates me today.

architecture — designing and building buildings — also means changing public space, transforming streets, the cityscape, and having an impact on public life. what is very tempting to me in retrospect (but maybe also dangerous in a certain way), is this combination of the social and political aspects of architecture and the notion of vanity: the architect is someone who is in control of the public environment and everybody observes his or her work.

legal / illegal, cologne, germany (2004)

image © julien lanoo

JL: actually, in a way, control is a defining feature of the compositional activity that characterizes your work, which is also aesthetically released. yet it seems that you give your architecture a lot of freedom — all of your projects are very site-specific, but once you leave a building behind, it inhabits itself and creates its own destiny. how do you achieve this?

MH: I always like to push design to a certain limit. each project is an opportunity to question how far I can push a concept, whether it’s in terms of its spatial dimension, its material properties, its engineering, or even its legal aspects. for example, legal / illegal is a residential, mixed-use building, and the interesting part was to push the limits of what I could achieve on the level of bureaucracy in this situation — the legal dimensions of architecture. this resulted in a building which is on the one hand a very direct response to its local conditions and the local code, but, at the same time, there is an object quality to the building.

I do not see it as a foreign object, but as a commentary on the existing urban context and the abundance of rules and regulations. in mainz, I worked on theoretical aspects — about the contemporary significance of ancient jewish traditions. what could be the result of learning from jewish text exegesis and early medieval life in the diaspora. to what extent can we push this in the production of architecture. explorations like these lend a certain kind of freedom.

ballet mécanique, zurich, switzerland (2017) | read more about the project here

image © yuri palmin

JL: what about your latest built project in zurich? in a recent article for the new york times, you mentioned that ‘it’s totally not swiss, but it’s also a building that could only be built in switzerland’.

MH: indeed. I quite like the ambiguity aspect of the building. I was lucky enough to work with a wonderful client, an art collector who was very open to a different approach to architecture, and the idea was to capture the transformative quality of kinetic art that she is collecting. I understand this building as a very close reading of its context — it’s located 100 meters from le corbusier, very close to lake zurich, in a very traditional bourgeois villa. it resulted in a building that on the one hand is perhaps very different from what we would conceive as traditional, contemporary swiss architecture. it is different in the sense that it is colourful, playful, there is a kind of humor, it is not orthogonal or dominated by concrete, at least not on the outside. it also undermines the notions of stability and structure, that are so fundamental to swiss architecture.

maybe I’m just listing some clichés here, but to a certain extent, they do represent what we think of as contemporary swiss architecture, and this building doesn’t conform to that. yet it absolutely relies on the fantastic craftsmanship that you can find in switzerland, on the perfect execution of the architectural details, on swiss building culture in general, and on the culture of the client and her appreciation of architecture.

JL: you are currently working on the tambacounda hospital in eastern senegal. what comes most naturally when designing in such a climate?

MH: all the research that I’ve done over the years on architecture on the african continent is now gaining the dimension of practice. I am certainly not an architectural historian. I am an architectural practitioner, and I am extremely happy about getting the chance to be able to build there. I was approached by a foundation to participate in a competition to design a hospital in eastern senegal. initially, I was very skeptical. on the one hand I was very interested in the context, the geography, and in the program of a hospital. yet, I thought the vehicle of a competition was not really the right one. it didn’t seem right that ten architectural offices located in basel, london, berlin and new york develop proposals for a region that they have never visited and for doctors and patients that they have never spoken with.

I thought that the competitive process was not the correct approach, but rather a collaborative process. so my response was to propose a research project, instead of an actual design proposal. I wanted to convince the client that before we could actually design something, we should first do a study on the climate, the region, the doctors, the nurses, the patients, and the local crafts and building techniques. only then, we could develop a design out of that. I was extremely happy that the client was open to doing this, and after an intense research phase and exchange and workshops with the local actors we developed a design proposal. now we are starting the construction at the beginning of this year.

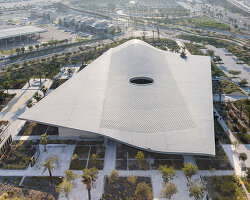

tambacounda hospital, senegal

image by play-time © manuel herz

JL: you’ve done an extensive investigation on architecture on the african continent previously. can you tell me about your research on human migration, and what are the overriding concerns in your studies?

MH: I have always been concerned with the social, and socio-political, aspects of architecture. as much as we, as architects, are involved in form and space, they don’t exist outside of a socio-political context. so I think we have to be aware of the repercussions of architectural and spatial urban production. we are not innocent. we are not these naïve designers — in the limited sense of this term — making pretty forms that have few repercussions on a social level. I wanted to investigate the political dimensions of our discipline, and I’ve always been interested in the topic of migration. it was in the mid-2000s that this notion of refugees, camps, and camp-like spaces became ‘popular’ within the architectural sphere. this was due to writers and thinkers like the italian philosopher, giorgio agamben, and architects were using terms like ‘spaces of camp’ and ‘spaces of control’. but I was skeptical how architects were using such terms, and what kind of conditions these terms were really reflecting. so, I started travelling to central africa to look at and study refugee camps. I wanted to understand our role as architects in the context of refugee camps, and what this reflects on our discipline. it was not commissioned work, but rather work generated purely out of a kind of self-initiated interest. I was just really motivated to understand these terms and to try to analyse them.

I developed an analysis of spaces of refuge in different locations on the african continent — what kind of spaces do refugees produce when they have to flee their home countries and home regions and set up new places of residence in a foreign country. while these spaces of refuge are usually seen as either spaces of misery, or spaces of exception in which refugees are not in control of their own lives, I was interested in the hypothesis that there is possibly a certain kind of emancipatory power, or the power of a new beginning, that these spaces could offer, and, that the refugees could use and appropriate their spaces as kinds of spaces of potential — social potential, political potential, cultural and economical potential. this is what I wanted to explore in locations such as nairobi, eastern chad, and the western sahara.

architecture can have an incredible influence or power in such places, whether for good or bad, it can be quite decisive in these contexts. but what fascinates me is the notion of dilemma that our discipline finds itself in: on the one hand, architecture is doing something ‘good’ — protecting people, saving people’s lives, and so on. but, simultaneously, it’s also often making a situation worse, or creating new problems, such as forcing or creating permanent situations out of temporary ones, creating new displacement, or even blocking solutions to a political conflict. so, this paradox of doing something good and bad at the same time is something that I think is very interesting conceptually, and it goes back to the core of architectural production. when we build, we always construct something in a positive way, but we also always screw things up.

pavilion of the western sahara at the 2016 venice biennale | read more about the project here

image © iwan baan

JL: what about your pavilion at the 2016 venice biennale?

MH: I had been doing research on western sahara for many years. in terms of aravena’s topic, it was literally a front line. the camps were located just few kilometres away from militarized and mined wall and borderline that morocco had constructed to occupy the western sahara. the urban research that I was doing there was literally ‘reporting from the front’. I was extremely glad to hear about the topic, and my intention for participation had several layers. first of all, I wanted to do a project with the refugees, in a way that didn’t result in me speaking about them on their behalf, but rather a collaborative project.

I wanted to work on the topic of the ‘national pavilion’, which is so fundamental to the venice biennale, and wanted to create a national pavilion for a nation that doesn’t have a national territory because it is a nation that has been exiled. this turns the otherwise quite conservative and conventional notion of the ‘national pavilion’ into a very political statement. I wanted to test the limits of the venice biennale as an institution in itself and see how we can give the national pavilion agency. and, thirdly, together with the refugees, we wanted to represent the spaces in camps, not as humanitarian spaces, nor as spaces of emergency, but rather to represent their architectural production on the same level as all the other architectural exhibitions at the biennale. the spaces and buildings constructed in the camps are often of a very high quality. there are some schools for example, featuring great designs. if we can acknowledge their architectural quality, and represent them as architecture with a capital A, rather than as emergency solutions, this gives some kind of honour and decency to the refugees and to the camps as spatial environments that are consciously shaped by their inhabitants. it is also a novel way of understanding refugees as agents of their own destiny.

JL: what made you decide to make a book about african modernism?

MH: I have been travelling to the african continent very frequently since the 2000s. on several visits to nairobi, while we were doing urban research in the context of ETH studio basel, I noticed the architecture from the ‘60s and ‘70s that I didn’t know about. I was struck by the aesthetic and architectural qualities of the buildings. they are not only well designed, they also hold a very interesting, complicated position within the political history of the country.

the buildings were instrumental in the process of nation-building. because most of them were designed by architects who were not based in or didn’t come from kenya, they also exposed many contradictions and dilemmas. they carry a certain kind of historical baggage, that is uneasy, interesting, and which I wanted to investigate. so I started a research project documenting the architectural production of the 1960s and ‘70s, the years following the decolonisation of most of the countries in sub-saharan africa. it is an investigation of the role of architecture during a period of political transformation.

kenyatta international conference centre, nairobi, kenya

image © iwan baan

JL: there is an ongoing discourse on whether architecture results in a new history, or history makes new architecture. how do you perceive this? what do you think the duty of architecture is?

MH: it always works both ways. the kenyatta international conference centre in nairobi, for example, was very influential in shaping the country: the united nations came to nairobi partially because of this building. although not the only reason, this building is also one of the reasons the UN decided to set up the headquarters of UNEP (united nations environmental program) and UN-habitat in this city, and this eventually led to nairobi being chosen as one of the UN capital cities. so, this building has had tremendous impact on the country’s political development.

by telling the story of a building, we can uncover the story of a city, or even a nation. in a way, a building becomes a witness, and gives a testimony to history. in architectural history, we often tell the story of a building’s design, planning, foundation, then its opening, and we usually stop at that point. but a building’s story doesn’t stop at the time of its completion. it is actually from the moment when a building is inaugurated, and the following forty, fifty or sixty years of its life, which is the interesting story to tell. by telling this story, the building becomes a witness to the political and the social transformation. it is not so much about the chicken and the egg [story] — whether a building influences a society or a society influences architecture, but rather about using buildings as a reading device for our social political context.

portrait of manuel herz in basel, 2018

image © julien lanoo

happening now! partnering with antonio citterio, AXOR presents three bathroom concepts that are not merely places of function, but destinations in themselves — sanctuaries of style, context, and personal expression.