issa diabaté is an architect from ivory coast who, together with guillaume koffi, leads koffi & diabaté architectes. after graduating from yale with a masters in architecture, diabaté worked at a number of high profile firms, including that of jean nouvel. in 2001, issa diabaté joined forces with guillaume koffi to form koffi & diabaté group. to learn more about the practice and the projects they are working on, journalist joana lazarova spoke with the ivorian architect who explained his work in more detail. read the in-depth interview, beautifully illustrated by julien lanoo, below.

let’s start at the beginning – at which point did you decide to become an architect?

ID: I decided to become an architect when I was 13. I discovered architecture through an internship at the practice of a friend of my father and I really fell in love with architecture. however, I did not go straight into studying architecture when I finished high school. I did four years of finance and business administration because I thought it was a more secure profession. nevertheless, I kept my interest in architecture all the way through my undergraduate studies and opted for a minor in fine arts (photography, painting, sculpture, and drawing). by my third year in finance, I decided that architecture was actually what I was made to do. so despite all the other concerns, I reconsidered going to architecture school at the master’s level. in the end, I applied to do a master’s in architecture at yale.

what do you think the role of the architect is today?

ID: I think that the role of the architect has to become much larger. architects work nowadays on a very specific level of the building and they no longer function as the ‘grand maître’ as they used to be at the time of ‘renaissance’, when they could control the idea the entire way up to the built result. unfortunately, the trade of architecture in the world has gone the other way and has become a very specialized area, especially at the corporate level.

I think that the crisis that architecture is currently undergoing expresses the need to come back to the position where the architect masters the process as a whole, from the idea to the finished product. this is pretty much what is taught in school: observe, think, take a lot from other disciplines, and mix it together to bring something new. I think our role in society should reflect that. our role should go beyond the building; our role should be very critical of the direction society’s going in and be very inventive about ways to move forward.

issa diabaté is co-founder of koffi & diabaté group

image © joana choumali

ID (continued): with the scale and speed of development in africa at an unprecedented high, working as an architect in our context should be driven by a different approach to our profession. an architect has to be a source of proposals to the government and to the people. he should be able to materialize ideas, a vision, through acts and concrete projects, to reach the final goal of transforming the urban landscape.

it’s not enough to just provide infrastructure. you need to anticipate how cities will function and then develop different nodes or centers that focus on relevant social amenities and commercial opportunities — especially at a time when we need to be resilient in order to incorporate the constantly changing conditions (e.g., demographic growth / rise of the middle class / new rise of this in the age of social media).

what research is currently informing your practice the most?

ID: as architects, we need to know the people, understand their habits and culture, and respond appropriately to their social, cultural, and climatic environments. at koffi & diabaté, beyond formal research, one element that is informing our practice is very informal. it is done through observation of what is going around us physically (building) and sociologically.

the assinie-mafia church

image © julien lanoo

ID (continued): we can see that our population is changing very fast in terms of size due to exponential growth and also due to technology. technology has become very present in the way that younger people live their lives. we must take that into account if we want to be able to anticipate what architecture (in our context) will be in the future, and most importantly, the systems that we are creating for tomorrow. systems of living, eating, enjoyment, work: all of these are being totally re-configured in the light of technology as it allows for much faster connections between people.

the assinie-mafia church

image © julien lanoo

ID (continued): hence, the need to rely on one source is becoming peripheral. increasingly, we are getting used to relying on multiple sources and cross-references to create our own truth.

this is mainly how we need to feed the architecture that we want to create for tomorrow: cross-referencing from different experiences in order to create our own truth.

the assinie-mafia church

image © julien lanoo

the ivory coast has one of the fastest growing economies in sub-saharan africa, according to the IMF’s latest world economic outlook, and urbanism, infrastructure, economic development, and social equity are some of the topics of the important discussions. what is in your opinion our discipline’s actual role in the process?

le plateau in abidjan

image © julien lanoo

ID: it’s not so far away from architecture. the way I see architecture, and design in general, is about being able to capitalize on other disciplines: what they can bring in terms of information and vision. architecture and design are part of all those issues. architecture must be central to those issues in order to create something new, something progressive, something that responds to the different needs of society. also, architects should take these issues into account — because we do understand the urgency of rethinking things.

for instance, if we talk about urbanism, the role that architecture can play in it is quite obvious. such a role is less obvious when we are talking about economic development and social equity. but the truth is that architecture is also a big player in the management of these issues. if you take for instance social equity and you start looking at what happens in the informal neighborhoods, what you learn is actually very rich in terms of information and how that information could actually inform the formal world. through the observation of the informal, we can see a much more flexible world. I think we should learn from that flexibility and bring it into the formal world. in order to feed the ambitions of the future, we need to get such input and figure out how to accommodate it in the light of much more important issues regarding the contemporary world. being too formal kills resilience and creativity in a world where we need to rely on inventive solutions to solve unprecedented situations.

cocody, abidjan

image © julien lanoo

ID (continued): before architecture can have an impact on social equity, social equity should have consequences on our practice. when you understand the need for social equity, then you can model your practice to accommodate the way social equity works. for instance, if you take a neighborhood like adjouffou (an informal neighborhood in abidjan), you will find that there is a very strong social structure. and then the question is not how do you make this informal reality become formal but rather how do you take the social structure of this informal world and apply it to a more formal environment. this is how architecture can be enriched by social equity and can re-inject observed principles into the process.

the two mains issues that are having an impact on our work today are sustainability and the digital world (how things travel so fast and how the world is connected in real time, no matter where you are.) so the challenge for african architects is to determine how our experience fits into the global world and how we then influence it (which values).

we are already starting to see that with social media. we can also compare the way social media works in a formal environment with how it works in so-called ‘informal’ spaces. we can already start to see differences. in the formal, people still rely on the official source (from an official website from which you can download information). but in a place like the ivory coast, you will seldom find official sources or data that are reliable. therefore, the source becomes the people around you who have gone through the same thing and who share their experience with you. there you are in a position where you can cross-check the answers that you get. I will say that we get much more valid information that way because such information has been already tested.

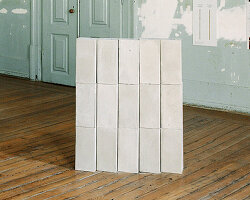

urban development in assinie-mafia

image © julien lanoo

can you tell me about koffi & diabaté’s ideas on housing and urban development?

ID: koffi & diabaté has been exploring issues regarding housing for years now. the rapid growth of african cities has given us the opportunity to develop new urban forms and types of dwellings designed as an invitation to live differently, in a sustainable environment adapted to local cultures.

the main reason why we became architect-developers was to enjoy the freedom of exploring urban issues. if you work on a building, you don’t have much impact on a neighborhood. that is why it has become important for us to no longer solely work on single buildings but rather focus on the entire ecosystem.

over the last two decades, a lot of things have changed: people’s visions have changed, the younger population is aspiring to other things, therefore housing and development ventures have had to adapt to this new reality. it is very difficult to quantify fundamentals into a body of academic work. it is more the result of our observation of the city, of younger people, and the changes created by technology (e.g., facebook, mobile banking, etc.) – what are they looking for today? are they still aspiring to own a house with a pool? what are they looking for in social relationships? these are definitely things that we are looking at.

urban development in assinie-mafia

image © julien lanoo

ID (continued): through these analyses, we generate a new model of housing as we respond to the way that society is evolving. we are at a time in which people realize that whatever needs to be invented for tomorrow has to be novel, innovative, and should rely on multiple experiences from the world as a whole, mixing experiences from different cultures, places, localities, etc., in order to create something that works within our respective, contemporary context.

the bamboo house in assinie-mafia

image © julien lanoo

so, in a way, your work incorporates strong social missions. the urban project in assinie-mafia, for example, aims at constructing self-consciousness. can you tell me about its impact?

ID: what we have been doing in assinie-mafia has been very interesting, it has been a way for us to test ideas. it is like a laboratory of experimentation. assinie is a small village and it is a lot easier to test things that wouldn’t have been done in abidjan.

the bamboo house in assinie-mafia

image © julien lanoo

ID (continued): first, the notion of lifestyle is an important aspect in the design of koffi & diabaté houses in assinie-mafia. as it is indeed a coastal environment, the link between interior and exterior is totally different from that of an urban environment. assinie-mafia has allowed us to test a lot of ideas – and often very simple principles – with regards to sustainability and the use of local materials. it has been very instructive in that regard. one of our goals was also to achieve climatic performance through natural ventilation and lighting, passive building in terms of energy construction before relying on green technology.

the bamboo house in assinie-mafia

image © julien lanoo

ID (continued): secondly, we have also managed to create a form of social experimentation aimed at bringing people together to work in order to achieve a unified urban environment. in the mid ‘90s, we designed a simple landscape model for the front entrance of a house we had built. people loved it so much they started to implement the same thing in front of their own houses. year after year, neighbors have created gardens in front of their houses, naturally contributing a part of their plot to the public urban space. when you see the area now, you could easily think it was the result of formal urban planning, when in fact it wasn’t.

urban development in assinie-mafia

image © julien lanoo

ID (continued): the lesson for us was that you have to take initiative: when you show people the way to proceed, when you offer something of a model, people follow, especially when they can see the results. here, every neighbor was invited to participate in the making of a new urban environment; this was a very informative experience for us in terms of human psychology and sociology (experimenting with the ‘how’).

we can definitely transpose the same thinking onto a neighborhood in abidjan. for our next project in abidjan, ‘abatta village’, an important part of our work is looking at how people can claim ‘moral ownership’ of public space. what is the mechanism that we need to put in place in order to nudge them into taking care of the public space?

public space in assinie-mafia

image © julien lanoo

could you tell me about ‘les résidences chocolat’ in abidjan? this project is creating a model which is defining new standards within the city and is aimed at conforming a way of living that would seamlessly match local needs with those of a metropolis.

ID: this project, a high-end residential compound with 14 townhouses and 18 apartments, amounts to 32 units per hectare. the notion of densification here was key, and an important design element was an emphasis on common space. we started with a high-end project because we wanted to inspire emulation. in order to offer a new model of living, we built a high-standard villa with a surface area of 260m² on a 400-m² plot. the traditions inherited from the prosperous period of the ivory coast would have led us to build 450-m² villas of on 2000-m² plots. this new scheme of life, accepted by the people able to buy a high-end product on a tiny piece of land, is more easily conceivable for the middle class, thus creating a new model in terms of lifestyle aspirations.

les résidences chocolat in abidjan

image © julien lanoo

ID (continued): it is lot easier when you move to a much bigger population to also implement densification, even with much smaller pieces of land. it is important to create this type of dynamic in a city like abidjan, where we know we are lacking in land capacity. we are starting to feel congestion, and having a lot of problems with traffic. so we need to propose a new vision of dwelling. we also need to lead people towards mutualizing such things as for gardening, security, energy, etc. so it makes a lot more sense to put people on a limited piece of land, where their resources work better together than separately, all the while diminishing our dependency on cars and introducing a new approach to mobility.

les résidences chocolat in abidjan

image © julien lanoo

ID (continued): at ‘les résidence chocolat’ for instance, you have one security system for 32 units, you have a gardener who takes care of the entire compound (for both individual and common spaces), and you have a generator that works for all residents. at the end of the month, when you accumulate the cost of all that, it’s a lot cheaper than if you had these same expenses in a house independent from a compound scheme.

for abatta village, a mixed-use compound with 226 units, we are using the same philosophy on a much larger scale (in terms of generation, income, and typology). we offer townhouses and apartments with 2 to 5 rooms. the compound also includes office space, and a sports center with a swimming pool and a gym.

if a person decides to live and work in this environment, he or she could do so without having to use a car to get to remote destinations. at koffi & diabaté, we are also hoping that by creating this new model, we will begin to see new lifestyle trends in terms of the residents’ involvement in their immediate environment, managing our shared spaces together and developing a common vision for our environment as a whole. this is something that is cruelly lacking in a place like abidjan. a program like abatta village is meant to teach people that community life is about putting resources together in order to achieve more, and also that when you put things together, you also get more back from your initial investment.

urban development in assinie-mafia

image © julien lanoo

does architecture need a more democratic approach?

ID: architecture, in essence, is democratic because we negotiate between different trades from the technical, sociological, aesthetic, and economic sides… negotiation has to take all of that into account in order for architecture to become democratic.

but in the end, the responsibility falls on the architects and their vision and ability to create something new. they have to be inspired by different sources, all the while being able to claim ownership for their vision. also important is the fact that one architect’s vision must be shared with at least a cluster of other architects; that is how architecture can have a more democratic approach: by working together toward a common vision, a common goal.