morphosis architects is an interdisciplinary architectural and design practice based in culver city, los angeles. founded in 1972 by design director thom mayne, laureate of the prestigious pritzker prize in 2005, the firm employs an uncompromising methodology of design and research that has produced countless forward-looking and iconic buildings and urban environments across the globe. their work ranges in scale from residential, institutional, and civic buildings to large urban planning projects, including the emerson college los angeles (2014), giant interactive group headquarters in shanghai (2010), and 41 cooper square in new york (2009). as their name, morphosis, suggests – derived from the greek term to form or be in formation – the firm and their work is dynamic, showcasing their constant evolution to the shifting and advancing social, cultural, political and technology influences of modern life.

emerson college los angeles center, los angeles, CA, USA. 2014. image © iwan baan

(main image: perot museum of nature and science, dallas, TX, USA. 2012. image © iwan baan)

see more about this project on designboom here

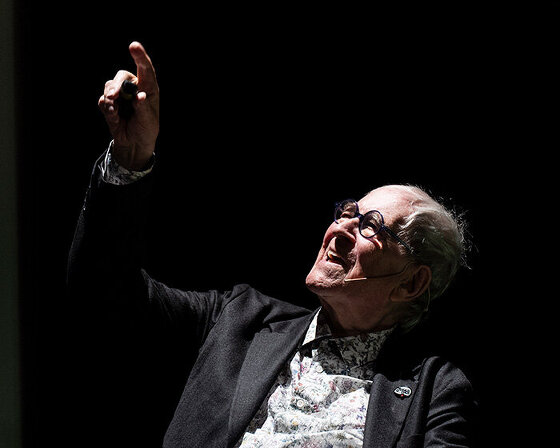

bachelor of architecture from the university of southern california (1968) and master of architecture from the harvard graduate school of design (1978), thom mayne founded morphosis architects in 1972 as a collective architectural practice that explores the cross-disciplines of research and design. as design director and thought leader, mayne guides the overall vision and project leadership for the practice. alongside his esteemed career, mayne has remained active amongst the academic field, most notably co-founding the southern california institute of architecture (SCI-Arc). he has gone on to teach at an array of renowned schools ,including columbia, yale, harvard graduate school of design, the bartlett school of architecture in london, and at present, at the university of california, los angeles.

thom mayne

image © morphosis architects

meeting at morphosis architects’ head office in culver city, los angeles, designboom sat down to interview design director, thom mayne. during our discussions, mayne provided intriguing insight into his background, delving into how he first got into the field of architecture, how he founded his own practice, and the origins of SCI-Arc. as well, mayne further speculated on the evolving design scene in LA at present, the misunderstandings of humanitarian architecture, and the importance of communication for architects.

designboom (DB): could you tell us about how morphosis began, and the origins of SCI-Arc?

thom mayne (TM): I am a person that has never established long term goals — I live in the present. I grew up in the 1960s when it was part of a time that you absolutely lived in the present. there was no long term ambition of having my own office, things just happen in my life and it has continued to be that way.

I came out of a time in architectural education when the ‘modern project’ was disappearing, and was, in effect, exhausted. most of my time as an undergrad was spent seeking out peers that were involved in very experimental work, were challenging all historical models, and were looking for a completely new entry point into architecture. I came out of school in 1968 with a huge appetite for question asking; I was looking for some new model, as I felt like we didn’t really have anything in place to work from as a conceptual foundation. so the first work we were doing was analytical in nature – we were searching for the right questions, and for the right basis from which to address them.

scaled models in morphosis architects’ head office in culver city, los angeles, USA

image © designboom

see more about this story on designboom here

in a way, my education was actually more appropriate to urban design and planning. I ventured in that direction first, starting with the city redevelopment agency and then moving to gruen associates who at the time was known as a think-tank, and had a huge investment in the education and mentoring of their staff. it was where a lot of young people wanted to start work; they took care of you. they trusted young people and saw their education as part of their mission.

while at gruen, a friend of mine offered me a position to teach at Cal Poly, which I took, and so left gruen. at the time, it was very much a chance for me to continue my education through guiding and teaching. also, it allowed me to ask questions and think about what it meant to be an architect, kickstarting my conversion from planning and urban design back into architecture. I taught there, alongside jim stafford, for a year and then we started a practice together. I was 26 or 27 years old: we just started something and called it morphosis. it was not ‘work,’ it was all about ideas and aspirations to realize them. it was the working arm of our academic connection in a way. it was very much formed through our interest in rethinking architecture outside of the singularity artist, architect. at that time, architecture was seen as the production of a personality like the frank lloyd wright character, and we saw it as a collective activity that was much broader than that. our approach was very much influenced by the archigram boys who were at UCLA at the same time that we were at the university of southern california.

it is really interesting because before I really got to know peter cook I met him as a kid. I was a senior at the university of southern california and I was going over to UCLA because I found it much more interesting at the time. this was because the archigram boys had just arrived in los angeles. I was totally fascinated and I immediately met ron herron, and as a kid, I was precocious, but I wasn’t shy about talking with them. I met the whole group and I was fascinated!

41 cooper square, new york, NY, USA. 2009. image © iwan baan

for our practice, we didn’t want to use our own names as we wanted it to be broad. we spent months looking through thesauruses and eventually came up with ‘morphosis’ — translating to the development of form. its big generic idea allowed us the flexibility to work on anything interesting that had to do with design. it meant that we were absolutely using archigram’s notion of a collective practice and malleable, flexible, organic people that can adapt to various kinds of problems.

a disagreement broke out at the end of that year at Cal Poly, and six of us were let go. from that, we started this school, where we worked for two years without a salary. just about the total senior class of Cal Poly left and came with us. imagine that happening today, it wouldn’t be possible! just six people decided to call it the southern california institute of architecture (SCI-Arc), and bought a warehouse in santa monica, which was right next to where our office was at that time, surrounded by the artistic activity happening in venice. it was definitely focused on breaking away from a regulating authority, which allowed us a certain kind of freedom. it was without any shadow of a doubt, explicitly and implicitly focused on innovation, research, rethinking, and understanding what architecture was and wasn’t, and the role of architecture within formal and social terms. as luck would have it, it just kept growing, and by the third year, we could actually draw a salary. jim and I had morphosis as well now, so we were just trying to pay our rent by doing anything we could do for work. by the third year of teaching and practising, we decided to separate. I kept morphosis as really, it didn’t mean anything. we didn’t have anything other than a name and an idea. I kept going with it and just before we split up, we won a competition with PA for our first project; the sequoyah school. if you look at it, it is straight archigram. I think that it is totally about transforming to climate conditions, being made by students, and is all about flexibility. jim and I were working on it with two of our students; one of them became my partner michael rotondi, and the four of us won that competition. this was the first time that word got out to the world that morphosis existed. at that time, publications and art museums were hugely important to architects, and PA was one of the central awards program. right after that, we heard from a lot of other publications that wanted to publish the work as well. it started this process of becoming more well-known.

hypo alpe-adria center, klagenfurt, austria. 2002. image © christian richters

DB: how did things evolve from there?

TM: after 10 years, I had a continuous practice of five to 15 people, who were my students coming out of SCI-Arc. we were getting little pieces of work, most of them residential and research based. I was still hugely invested in teaching, and now SCI-Arc was growing even further. it got accredited, and I was also involved in starting a graduate program, which eventually led to me taking a year off and obtaining a graduate degree from harvard. we were at a point then where I had a legitimate practice – still a little practice, mind you, but no longer just me, michael, and a few students. the next transition of the company was when michael and I separated in the late 1980s. again, I kept morphosis and he started his own practice. there was a downturn in 1990, where I had 25 people or so, but no projects really got built because of the 90s crash. I spent two or three years repairing things in order to get back into business. after this, I knew we would take off. we got our first large project, which led to working in austria, toronto and los angeles. that was the beginning of a continuous pattern of work for us. by that time, we had published quite a few books, and had been documented very extensively. we started winning lots of PA awards, so much so that I kind of lost track because we were extremely active.

wayne lyman morse united states courthouse, eugene, OR, USA. 2006. image © tim griffith

DB: what were your ambitions when you started out?

TM: I never really had any interest in becoming something. lots of people say that their goal was always to become an architect, but for me, I had no idea what I wanted to do when I was a kid. I had a hard time just getting out of school. I was never interested in the organizational notion of school, I never did very well with it and it was never comfortable for me. I left school with no clue, but things just fall in place at certain times. one thing however, is that I am part of a generation that made stuff. in the US, I can talk to my other architect friends who are also from my generation, and some of the things we have in common is that we did come out of a suburban world where we made things – models, cars, etc. actually, first we would make the models, and then we would immediately change them, riff on them.

for example, we would take apart go-karts and then reconfigure them to become better and faster. the straight-forward mechanics of this activity were comfortable for me and I had a kid-like pleasure in them (still do). it was definitely the one impulse that pushed me into architecture, and it just came quite naturally. the intellectual and conceptual aspects of making and architecture came later on. so, to summarize, I started in architecture by the simplistic notion of the pragmatics of stuff, the process of making and materials. then, through my education — and absolutely through teaching — the expansion of my awareness of the intellectual, social, political aspects developed. I am often traveling around the world, and you can see that architecture is becoming globalized through a shift in the media coverage. LA, which was this very powerful place architecturally, but was provincial, is part of a broader culture now. my generation is now being invited to lecture all over the world, expanding those friendships even more so. with this expansion comes the opening up of the whole definition of what architecture is, particularly on a conceptual and intellectual sense. one of the wonderful things about architecture, which I always try and communicate to my students, is this discipline which by its nature is expansive, but it can be started at a very simple level and demands you to move forward in multiple ways.

bloomberg center at cornell tech, new york, NY, USA. 2017. image © matthew carbone

see more about this project on designboom here

DB: how was the purpose or intention of SCI-Arc changed over the years? how has it remained relevant?

TM: SCI-Arc has remained this amazing place that is focused on innovation. it has a collective energy that is quite contagious, which is very unusual in a school that has run for 44 years. and it continues to evolve: it has just changed again as hernán díaz alonso has replaced eric owen moss as the school’s director. I left in the 90s and have been a professor at UCLA since then, but I am still involved in the board — it is my baby, I will never leave it. what has been so fascinating is that it has always had an anarchistic sensibility but as an oxymoron, it is somehow an institutionalized anarchism. there is a sense in the place that is more powerful than any leadership. SCI-Arc has this energy that comes from a concept of education which is based on question asking, and some quasicollective connection of ideas that overpowers leadership. it has maintained that energy and it has increased in its sophistication. if you were to go to a jury there, you would be bowled over by the consistency of high level work and by the level of energy that takes place — it is just amazing.

at morphosis, we still have an important sense of the innovative act and the notion of asking first principle questions that continually lead us to new ideas. however, the company has changed in a very different way — from a very small office dealing with quite simple problems, into an institution that produces vast differences of work types and scales that would have had absolutely nothing to do with this office 20 years ago. by its nature, it has been forced to become much more specialized in dealing with the kind of projects we have in front of us right now. it now has some hierarchy, even though I initially wanted it to stay completely flat on one level. looking at our environment, we all sit at a desk in the same space, and I try to keep this kind of sensibility, but due to the nature of our work and its specialization, it has changed quite radically.

sun tower, seoul, south korea. 1997. image © young-il kim

DB: you have worked alongside some other fantastic architects, many of which when their careers were starting out. do you feel that young architects today have the same enthusiasm and sense of camaraderie?

TM: I consider myself very fortunate and incredibly lucky to have grown up in LA in a particular time. I was working with the generation under frank gehry, who was the singular character of his generation. my group included major characters such as coy howard, robert mangurian, craig hodgetts, and eric owen moss. this fascinating group of people was producing really interesting work when they were just in their young 30s. there was this really interesting critical mass in LA between the three schools: UCLA, USC and SCI-Arc. all of us were teaching and were sitting on juries on regular bases, continuing conversations over decades, and questioning curious aspects of architecture. then all of us at some point, probably when we turned 50, went in our own direction. I would have said that the group here at that time, my colleagues, were on the artistic, cultural side of architecture.

this is another fascinating thing about SCI-Arc. it creates generations of these kind of groups. a lot of young, mid-40 people who are or were involved with the school, are now very well publicized. just to name a few: elena manferdini, marcelo spina, georgina huljich, florencia pita, tom wiscombe, hernán díaz alonso. they are all in LA, with most of them coming from, or are at, SCI-arc. it is a group of people that talk to each other regularly, have conceptual interests that bind them together, and all have their own foci, but are absolutely connected. I would say that at this point in my life, that aspect is enormously important, you cannot overrate it. you need a community and, as an architect, part of your own thinking is based on dialogue. it is how you are being charged from the outside, it can’t be all internal. these aspects still make LA one of the most vibrant, if not the most vibrant educational center in the world right now. I might be overstating it, but only slightly.

cahill center for astronomy and astrophysics at caltech, pasadena, CA, USA. 2008. image © michael powers

DB: do you feel that architects who teach are able to communicate their ideas more easily? particularly to the general public?

TM: I have these certain categories that are absurdly simplistic, but they help me understand and negotiate the field I work in. I define architects as those that teach and those that don’t teach — I draw a line between the two. by the nature of teaching, this usually also distinguishes the architects who are more invested in theory and research, and those that are more invested in practice and business. today, depending on how you want to cut it — I’d say 90% business and 10% culture of architecture — there is going to be an observable split between architecture as a business activity and architecture as an art form. the majority of architects teaching are in the art form category. with communication, I would immediately say that the teachers are much better, but then I realized that it is much more complicated than that.

when I was younger, I communicated through my visual world as if I was a musician. my work said everything I needed to say, I didn’t need to talk, but you can’t do that in teaching. when you have to guide somebody, even if it is extremely complicated or very subjective, you have to find ways of discussing it, and you have to expand your own literary abilities at the same time. it is extremely useful, in that sense, for refining your ability to locate and articulate a problem. so yes, I would say that all the architects that I know who teach are very articulate because they have to be, both in dialogues in juries and as they are communicating with their students.

on the other hand, there is a private, somewhat esoteric language among architects which very few people in the general public would understand. you might say that an architect can be very articulate, but won’t actually be able to ‘communicate’.

madrid housing, madrid, spain. 2006. image © nic lehoux

in the so called ‘real world’, maybe the business-sided architects know exactly how to speak, because they get what they want, they communicate, and they adapt—a very different strategy and goal than the people operating in the discourse of architecture. if you are in the business of architecture then you are responding to what that market is asking for. but I am increasingly searching for a third option–more of an approach inspired by say, a steve jobs or elon musk. if it exists, let someone else make it; I am interested in doing something that doesn’t exist yet. now, to achieve this my role is to communicate on shared terms, within cultural, political, pragmatic, functional, and environmental aspects. I see this as a critical strategy for any person who is interested in innovation, especially an architect who is trying to move things forward in some way.

so, to summarize, there are two very different notions of communication in architecture. what is so beautiful about practising and teaching is that you can operate on these two levels.

I will say though, there is a difference geographically as well. I have worked about 50/50 in this country and outside of it – if I am in britain and in europe, say, I can get much closer to speaking about the project conceptually with my clients than when I am building in the US. here, I tend to have to tone that down and speak within a certain pragmatic language. otherwise, it can work against you, even to the degree that you might lose the commission — it is that severe here.

7132 house of architects, morphosis hotel rooms, vals, switzerland. 2016. image © morphosis architects

see more about this project on designboom here

DB: in 2016, alejandro aravena won the pritzker prize and curated the venice architecture biennale. what is your feeling about architects taking a stance on humanitarian architecture or being more proactive in shaping the urban environment?

TM: there has been a lot of press focused on this same topic, which I think reflects a new (and unfortunate) notion in the general public that it is somehow unusual for architecture to have humanitarian dimensions or urban involvement. even more alarming is the press denigrating the decision, that the pritzker selection should have focused on ‘design’ and not social agendas. when I entered architecture, even as we kind of ignored history, we were conscious of the modern project as an undertaking at a societal scale. architecture was attractive precisely because, out of all the academic and creative pursuits, it was the one that maintained some sort of ethical position. I think that one of the things that connects architecture to this day, is the instilling of this either implicit or explicit notion of some common good, where somehow you are assisting and advancing society in some terms. but I’m not sure that this same understanding of architecture pervades the public’s conception of what architecture is and what it is supposed to do.

my sense is that there is some sort of larger movement going on, similar to what is going on politically, where people are attacking certain broad, collective ideas that were the mission of the 20th century. in architecture, this translates as somehow anti-design, and I can’t fathom the reasoning for it other than as design symbolizes self-expression, and that the use of freedom frightens people. right now, there seems to be a lot of people moving with the herd and are comfortable doing that. I can buy into this a bit because we all are creatures of habit to some degree. however, it seems that the speed of change is surpassing the capacity of huge numbers of people to support that change. I am talking about social, political, cultural changes, shifts in gender and shifts in institutions.

casablanca finance city tower, casablanca, morocco. 2018. image © morphosis architects

so alejandro aravena comes along, he is actually just like any architect in formal terms, but he is highlighted as focusing on architecture’s social aspects and I don’t buy it as a new concept or an alternative to ‘design’. I don’t know any architects today that don’t see architecture as a social art form; we are still deeply embedded in the history of 20th century architecture and its socio-cultural experiments. even the idea of separating design into ‘formal’ and ‘cultural’ spheres and comparing their legitimacy is troubling. the separation is dangerous because it is implying that architecture is dangerous in a cultural form. and to say that when you have socially responsible architecture, then you don’t have ‘real’ architecture, is nonsense.

there is a political split right now between those that seek difference and those people that yearn for singularity and somehow innately fear otherness. with architecture, there is an absolute parallel with this. there are people that still want, on one level, for the town to look amazing, but with the whole town’s architecture to fall under some single authority so that they feel comfortable that we all agree and all live under the same ethos. they still yearn for this even though it is a complete impossibility, because the first question is, ‘under whose culture?’

it is impossible to have any single dominance aesthetically nowadays. this works against innovation. architecture is symbolic, they want the thing that is a symbol of their dominance and culture. for me, I can’t disconnect this from an architectural discourse. it is a conservatism back to the art form because they are afraid. it is less about architecture as a social art form, it is about an attack on the art form. it is not about the social form, it is an attack on the rest of us. I will be talked about as absolutely someone who is totally embedded in environment, urbanism, advancement of social ideas to someone who knows me and my work. for those that don’t, I am going to be a weird character who has another ego.

beirut new embassy campus, beirut, lebanon. 2023. image © morphosis architects

DB: which architects or designers working today do you most admire?

TM: the friends that I admire are: wolf prix and frank gehry for all different reasons; steven holl; richard rogers, for all the reasons why he is totally fascinated in urbanism; and eric owen moss. they are characters who are fighting for their culture of architecture. all of them have somewhat different notions of its connection, whether this is focusing on sustainability or urbanism etc.

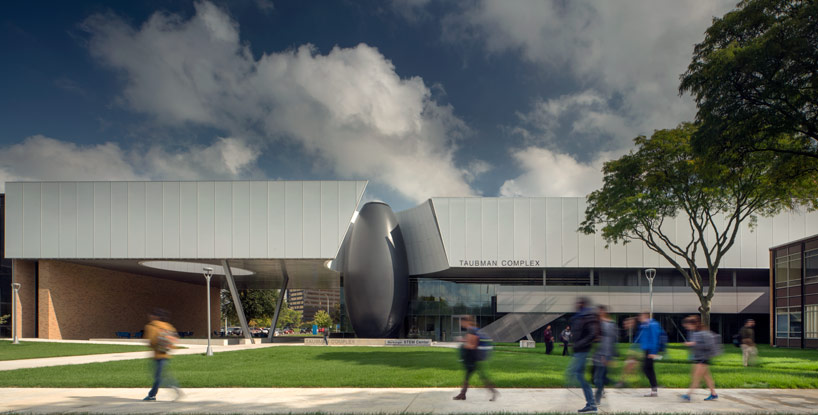

taubman complex at lawrence tech, southfield, MI, USA. 2016. image © nic lehoux

see more about this project on designboom here

DB: what projects are you team currently working on?

TM: our projects are super diverse right now. we are working on a huge research center in soeul, which is a really interesting project environmentally. it has an external skin going on, which will be the most advanced that we have done to date. we are doing our first really tall tower (350 meters) in shenzhen, china. we separated the movement so that you can walk over bridges between the buildings. there is no core so you walk into a big space and then look down on the city from a 15 meter glass bridge. I am really intrigued in the basic restructure, the organizational aspect of this work, and that was how it all started. it is at the 50th floor right now… we have another one in casablanca which is under construction… we are also doing our biggest project, in beirut, which is the new U.S. embassy.

kolon future research park, seoul, south korea. 2018. image © morphosis architects

see more about this project on designboom here

DB: overall, what you say is your strongest asset and how have you developed that skill over time?

TM: it is hard to answer singularly. if you asked me what my favorite color was or even worse, what city was my favorite, then I still wouldn’t be able to name one. I have about 300 and if you asked me next year, I would have 320, it just keeps increasing. I think at this point in my life, I have realized that I have a certain skill for dialogue that allows people to do their best work, and allows me to move fairly large groups of people into focus.

on my last count, there has been somewhere between 50 to 60 different practices that have come out of this office. I take real, real pride in that. I don’t get angry when people leave morphosis, I give them a hug and tell them to go for it. when young people start working here, there are two courses that they are going to take if they leave; one, they are going to grad school or two, they are going to start their own office. ahead of both options, they ask me to have lunch, where I already know what is going to happen. if they have been here for two years, then I am going to write a recommendation for them to go to the grad school. if they have been here for five to 10 years, then they are going to start their own office and I congratulate them – they are moving uphill. I take huge pride in this because I think of myself as much more than an architect now. at morphosis, I can teach in a more direct way than in an academic environment. this is because we are together doing a project in a much deeper and more meaningful level, as it has the reality and responsibility of what we are producing. 15 years ago, as the firm was getting much larger, I began thinking about myself as much more of a thought leader than a designer, which I would have never considered previously.

hanking center tower, shenzhen, china. 2018. image © tim griffith

see more about this project on designboom here

DB: what is the best advice you have received, and what advice would you give to today’s young architects and designers?

TM: for those at morphosis, and definitely my students, my advice has always been to look and understand who we are as human beings and how we perceive each other. this understanding is very relevant especially with all the changes that are going on in the world today. people need to work out what is most important to survive, not just in the profession of architecture, and it all starts with flexibility and adaptation. today, one has to be open and be completely comfortable in a world that is constantly understood as provincial. every idea is replaced by another one, every bit of knowledge is being updated by another piece of knowledge.

7132 hotel & arrival, vals, switzerland. image © morphosis architects

see more about the project on designboom here

for young architects and designers, and this is connected to my previous point, there needs to be alertness. we are in a world where you have to stay alert, you have to be engaged. alertness is absolutely connected to the necessity of adaption. you cannot disappear in architecture, it is not a private activity. it is connected as a social art form, and now more so, connected to even broader issues, such as sustainability, infrastructure and urbanism. furthermore, architecture is long term as we deal with projects that can range from lasting three to seven to 12 years to complete. it takes a huge understanding to realize that you are operating long term, with patience needed when working on one single project, as well as towards your own goals.

my last piece of advice is also inter-connected, but is a newer piece of advice as architecture has become more strategic recently. architecture is a private art form and a discipline within itself that has its own thrust, intent and set of interests that are interpreted conceptually. it is now more so engaged in the political, environmental and cultural aspects, and so, as the scale of the project increases, especially in urban projects, the work has to add another layer that is strategic. one has to make an argument within multiple terms so that it can be discussed in many ways.

happening now! thomas haarmann expands the curatio space at maison&objet 2026, presenting a unique showcase of collectible design.