ambrosi etchegaray is an architecture practice led by jorge ambrosi and gabriela etchegaray, whose studio (visited by designboom here) is located in mexico city. the duo, who are partners in life as well as architecture, founded their firm in 2011 and have since completed a growing number of projects in their home country. the firm was asked to curate the mexican pavilion at the 2018 venice architecture biennale and has since completed projects at casa wabi — the arts center set up in 2014 by mexican artist bosco sodi. both ambrosi and etchegaray are currently adjunct professors at columbia university’s graduate school of architecture, planning and preservation, a role that means they also have a base in new york.

to learn more about the firm, designboom visited ambrosi etchegaray’s studio in mexico city where we spoke with jorge ambrosi. read the in-depth interview below, and see photos from our studio visit here.

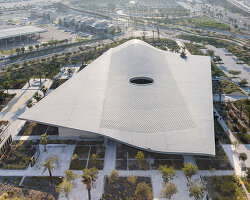

guayacan pavilion, 2018 — read more on designboom here

image by jaime navarro (main image by sergio lópez)

designboom (DB): how did your practice begin?

jorge ambrosi (JA): I worked with javier sanchez for some years and after that I started my own practice with a partner from 2003 to 2008. we dissolved that and 2011 I began the practice with gabriela (etchegaray), and we started ambrosi etchegaray.

DB: so you learned a lot before, while working in a different practice before starting your own. was it an easy transition or more difficult?

JA: the difference with other parts of the world is that mexican practices start really early in their career. maybe in other parts of the world you start your practice when you are 38 or 40 — you are not economically stable, but you have much more know-how of how to do things. in mexico you start really early, you don’t have economic support.

DB: where do the first clients come from?

JA: it’s always an issue how to get them — it’s like an adventure. some days everything seems easy, other days it’s not so easy, but you manage to find your way. you see a lot of friends that are losing the battle on the way, you keep going and I think it’s partly luck.

DB: are there many young architects in mexico?

JA: there are many architects, but for the amount of architects that come out of school there are not enough practices. there are hundreds of architects from schools and maybe 1 in every 1,000 architects has an office, even though maybe you don’t count 30, 40 really good architecture offices in mexico, which is a lot. but at the same time, it is not enough for the amount of architects that the schools are producing.

DB: which are the biggest studios in mexico that employ young architects?

JA: a mexican architect called sordo madaleno has a 200 person office — it’s huge and has huge projects. maybe you can count five or six really large firms in mexico working at that scale. you can also see firms from other parts of the world arriving to mexico to install secondary offices here.

casa volta, 2018 — read more on designboom here

image by sergio lópez

DB: when you founded your own firm, what were your goals? was there something different that you wanted to do?

JA: I think it was clear from the beginning that we like to do architecture. we like to do projects, but I do believe that in mexico we don’t have a lot of time for reflection. mexico is a lot about doing: you get a client, you get a commission, you get the permissions and in one year you are doing a building — even though you may be 23 or 24 years old, it’s very easy. you learn by doing, so after doing you start reflecting on what you are doing. when we started our office, maybe the first breaking point was when we were selected as the emerging voices for the architectural league in new york. it was really the first time that we had to sit and reflect on what we were doing, three years after we started our practice. we had some time for reflection and to frame our interests, and since then, lecture after lecture, we have been trying to develop what we were thinking. we tried to define an architectural framework that is focused on our practice.

the second breaking point was when gabriela started feeling a little bit uncomfortable about all this energy of doing, and not actually reflecting or thinking of things. she started to be more interested in curatorial practice and decided to do a masters course in curatorial practice. we arranged everything, the office and the family, and in 2016 we moved to new york and we still live there now. gabriela studied two years of curatorial practice and in the middle we were invited to be the curatorial office (for the mexican pavilion) at the venice biennale. everything started happening so fast. then, six months before she finished, columbia invited us to teach there, so we are now teachers at columbia. living in new york, and having that distance from the office and from mexico, gives us the final reflection that we needed to know our interests.

casa volta, 2018

image by sergio lópez

DB: what is the timing — when are you in mexico and when are you in the states?

JA: I come to mexico maybe every two weeks, for 3 or 4 days, and gabriela normally stays in new york because we have a daughter and we can’t travel so much. she stays in new york and I come to check the office. but before, we were both traveling every 15 days. I believe that this really helps us to focus differently and to understand that the thoughts that you have behind architecture, and the way you think and reflect on architecture, are more relevant and more powerful than the buildings at the end. the buildings, we enjoy them, but it’s more like a hobby — it’s really fun to do architecture and we like the projects and even the process, but I think now our heads are in a different place. yesterday I was in dallas giving a lecture about that; that we are in a kind of crisis, or a moment to stop doing so many things, and building so many things and to try do more research on the topics that we are interested in. I also try to produce books, we are doing a book now, and I try to produce an exhibition and a research program — we are also working on that — and a lot of things that go with an environmental way of seeing things and maybe also a more political way of thinking and a more active approach to architecture.

just thinking or trying to do statements, or even just writing in a magazine sometimes is much more powerful and gets to much more people than just a building that will be there and maybe people will see it, but it’s not so strong. in columbia they allow us to participate, the master is called ‘advanced architectural design’ and it is very open. we can understand the practice far away from buildings. that’s where we met marco [ferrari of studio folder]. when you see his exhibition of ‘the moving border’, he has this beautiful investigation that is architecture, but it’s also environmental and political. I think those kind of approaches to the practice are really becoming necessary for the moments that we are living in. a building for sure is not necessary, but that doesn’t mean it doesn’t have to be built. because maybe somebody needs a house and you have to build it, and if you don’t do it somebody else will, but it’s not necessary for the questions that are being raised for our generation as human beings.

IT building, 2016

image by rory gardiner

DB: you describe your approach as more theoretical at this point, but at the same time you have a team of architects working for you. how does that go, how do you approach a new project with the team?

JA: I think what has been good about this distance from the office is that the starting point of the projects have to be more about the content of the project. I think this happens a lot with me and gabriela between classes and when we are in our life. we don’t have the tools to produce and to see things, but we are always conversing about a project. it’s funny because when we are in mexico we are with the team and we have the tools, but we don’t have the time for these conversations. with the team we try to direct them to help us to produce plans, renderings, images, models, everything that helps us to understand, and when we take trips we try to gather with the chief of each project and try to communicate what we were thinking about and what’s the idea, where the brief needs to go.

IT building, 2016

image by rory gardiner

DB: you said before that maybe a new building is not needed and that you, in a way, try to understand the culture of the necessities of today in architecture. are they different from some time ago? what would you say are urgent topics in architecture now?

JA: I do believe in questioning the things that we do, even if we keep constructing architecture or not. obviously for environmental reasons, it’s a lot of energy to make a building, not just in terms of the environmental pollution that happens, but also the economical energy. does the money need to be invested in that, or can we dedicate that money for another kind of project, for society?

DB: but these are public issues, right? do they apply for a private client?

JA: I think they apply in some kind of way. for example, one thing that we decided recently is that we will never work again for developers. for a lot of years we worked for developers, but we realized that when you are working for developers, the real person you are working for is money — you are working for profit. I think we will never put our work and our minds to the service of profits, never. it’s not worth it and it’s a waste of time. but if a client has a necessity, a specific need for space, for something, if we manage to have some kind of similar ways of seeing life I think we can work for them. we still need the office because for a lot of years we have been doing that, so our way of life is based on the income that comes from doing projects. at the moment, we’re starting to get commissions or teachings, but it’s not enough as an income to sustain our lives, so we need to start making a transition maybe and create some platform that offers us a possibility to create our reality and our economical exchange with some different kind of format. I believe we are integrating that through curatorial projects, or we are doing a book and the making of the book is paying us, so we now have these formats of income, but it’s not the same as a project. actually 90% of the office is sustained by projects.

A PLACE: murals of the territory, 2019

image by sergio lópez

DB: are your clients from the US or mexico?

JA: they are mostly mexicans. most of our work is here. we have thought that now we are in new york if it’s worth looking for opportunities there, but at the end we say that we have the scale of projects and the kind of projects that we want. I think if you put in a list ‘what are your dream projects’, we have those at the office. so, why do we need to seek more projects, to compete with another market? we don’t see really a goal in that. obviously you always have that seductive dream of doing a project in europe, but at the end you say: what’s the reason to do architecture there? it’s like putting a flag saying ‘I’m here, I’m in europe’. I don’t know if that’s enough because what we like is to bring questions to the table. questions for society, for humanity, for ourselves. so, we can do that with the projects here in mexico.

DB: what are those questions which are nearest to your heart?

JA: I think right now our question is: how can architecture work as a medium to communicate some larger issues, like environmental issues? how does architecture manage to give us the space for consciousness or for awareness to some specific topics? because, for example, I follow a lot the work of olafur eliasson, and you see his work and he’s doing art always because it’s what he does, but at the end it’s communicating something more. he’s bringing awareness through his work. so how much more can architecture communicate and make it a medium to create other kinds of realities? I think at the moment in our office, we still believe that some of the projects we are doing lack that capacity. not totally, because they communicate some values that we are really proud of, but the question is, what else?

A PLACE: murals of the territory, 2019

image by sergio lópez

DB: is it mainly the environment you are most worried about?

JA: I think our worries are also political. the problem is the lack of interest, and that’s politics. how can we get more engaged with politics, with communities… sometimes I believe that some of these topics can become really trivial, but how can we be able to make some kind of a difference. right now we were talking with gabriela that we are going to make a kind of general checklist for our projects, and the funny thing is that when we just started talking about it, and we start putting some projects to see if it would work, we realized that all the projects check some of these topics, but they are not explicit. I think to communicate better, you need to make these topics really explicit in your work, and at the end you can really make it a statement. we have some years ahead, but I hope to achieve something there.

DB: do you have already some examples of works where you have managed to apply that?

JA: I think the project of vivero guayacan that we just finished last year at casa wabi. it was quite a statement in some kind of ways because casa wabi was made by tadao ando, the first pavilion was made by álvaro siza, and the other one by kengo kuma — and then they invited us to do this pavilion. we decided not to enter in the game of the pavilion, like something that could be photographed and shown, because I think that’s a risk with architecture recently. so we decided something more of a landscape intervention, and that worked really well. it’s incredible because they told us that it was the winning project in the iberoamericana bienal and we were happy for that because when we see it, we don’t see a project — it’s a landscape intervention and that’s it. we don’t see architecture in the way we normally see it. it’s funny that it was awarded with projects that are really buildings, it’s something different, but that kind of recognition has given us the capacity to say, ‘okay there’s different ways to approach things’ and maybe that’s an example.

milagrito mezcal pavilion, 2014

image by rafael gamo

DB: what’s your favorite stage of a project?

JA: I don’t believe there’s a favorite one. there are moments where I enjoy working a lot, and other ones where I don’t develop any work. at the beginning, when we don’t have an idea what to do, there’s a lot of anguish and stress, but then you know what to do and you get really motivated and excited, but then you have to translate that into drawings and it’s complicated. things start to get lost and you get stressed also, but I think it’s coming and going.

DB: so you are not only directing, you are still very executive in the office?

JA: yes, I love to be. I mostly work on sketches, sometimes I trace CAD drawings, not always, but basically all the images we are working with, the sketches and all that…we are very involved.

DB: so, as you are partners, do you discuss initially among yourselves? or do you discuss with all the people in the office?

JA: we mostly discuss between ourselves. we think we have changed so much in the last years and we haven’t had the capacity to make the necessary changes in the office. I think the office now is more like a company that helps us to put things into reality more than to help us to think, because of the distance.

milagrito mezcal pavilion, 2014

image by onnis luque

DB: are there any projects you are currently excited to be working on?

JA: there are two projects that we are excited about. one is really small in the south of the city. it’s the offices for a movie production company and the clients are amazing. they are a couple of mexican artists that are really famous, and it has been really incredible to work with them because somehow they are in the same age that we are, and they are also asking the same questions in their practice. they are doing this office because the production company that they had before doesn’t allow them to ask all these questions that they want to ask, so they closed the other one and they are opening this. so we understand each other and it’s a really nice project.

the other one is downtown in the center of mexico city and it’s a huge building with a commercial passage in the lower level that has this historical passage from the beginning of the 1900s, but it has remains from the 1600s. so you have a lot of moments in time, and we are adding to that structure a seven-story building with a hotel, a cultural place, and some working areas — so it’s really complicated. it’s a large project and we have been working on it for five years now. I think we will have five more years to go, but we are in a moment where we are starting to see the results and it’s becoming something really, really interesting.

ambrosi etchegaray’s studio in mexico city — see more photos from designboom’s visit here

image © designboom

DB: are you optimistic about the future of the profession?

JA: I don’t know if I’m optimistic with the world anymore. I read an article a couple of months ago that the whole topic was how to face everyday acknowledging and knowing the moments that we are living in. and, at the end, you have to put aside all that awareness sometimes, and do what you need to do: work at the office, try to pay the salaries of the people you are working with, try to not think too much about the issues, but then again start trying to change yourself and the way you participate in the world because we are obligated to that. we cannot keep doing the same things we used to.

I’m sure that if we don’t have the will to change, nothing will happen. but even though we have the will to change, maybe we are already doomed. but that doesn’t mean that the only chance of not getting there is changing. we need to change everything and it’s really hard because it’s not about changing something outside of you, it is changing yourself. we have talked about closing the office and jumping to a conceptual office that will do more idea-based work, but you’re scared to take that jump because you have to pay the rent, pay salaries, and you have children now to raise… but we need to think, we need to act, and, in a responsible way, start to make those changes, but quickly. so I’m optimistic, but I’m concerned also.

jorge ambrosi and gabriela etchegaray

DB: I think having children obliges you to be a bit more optimistic, because you want them to be there, and as much as you can you try to cultivate a setting that is healthy for them. meanwhile, in the past I think parents always thought it would get better and better: ‘maybe I’m not earning as much, but my children will have a better life, and so on and so on’… we are now at the point where everybody is saying, I don’t know where the future is heading. people get very pessimistic, and most creative people are very, very pessimistic…

JA: I do believe that becoming really pessimistic is like giving up. I think it’s important to try and make an effort to communicate some optimism because I do believe that it’s a way to put us somewhere else. even though it’s sometimes hard because the panorama is not so promising, but I think it’s important not to give up. for example, I love this statement of the triennale in milan that says, ‘okay now that we know that we are doomed, how do we design a nice end for this?’ it’s strong, but at the end you think, okay there are still things to do: let’s do a beautiful end, something that says okay, we screwed up the planet for the last 500 years, but at the end we realized it, and we made our best effort and we failed. until the day we’re dead we can still do things and that’s a responsibility… it’s also about enjoying. the fact that the future is not promising doesn’t mean that you can’t enjoy it, because it’s incredible to be doing things, and interacting with the world, trying to manifest realities, and thinking and reflecting on that.