bjarke ingels, together with friend and patron ian gillespie, knew early on that their 2016 serpentine pavilion would have a traveling life. as both ian — founder of development firm westbank — and bjarke both find more satisfaction from the journey of design than from the completion of a project, it was inevitable that the adaptive pavilion would live on after its run in london’s kensington gardens. since its recent unveiling in toronto, it’s clear that recontextualizing the project has a transformative effect. the undulating form is part of a new dichotomy — integrated into the dynamic urban street life and surrounded by heritage buildings — while in its first life, it existed as an object in bucolic solitude. in this sense, the duo can watch the project continue to unfold and reinvent itself.

at the pavilion’s launch in toronto earlier this month, designboom spoke with bjarke and ian about their working dynamic and design philosophies.

image by @westbankcorp

designboom (DB): let’s start by speaking about your role as patron, ian. what’s the dynamic between the developer and the designer?

ian gillespie (IG): at some point when you first start off the relationship, it is just a client-architect relationship. then over time, the relationship evolves and deepens. you start becoming collaborators and friends and you gain more trust in each other — even your teams start working together. in that way it kind of evolves.

bjarke ingels (BI): it’s almost like we’re ‘brothers in arms’ because of everything we’ve been through.

IG: you struggle those battles that give purpose to it. I think at the end of the day, the way you measure your life is how you’ve reacted to those struggles and how you’ve persevered. it’s not the end result, it’s the journey. these people come into your life and you don’t want them to leave your life because you’re being enriched by their presence. we always need to be working on one new project, because that process of working on a new project is the part that keeps me doing what I’m doing. I don’t get a great deal of satisfaction from seeing the building built, but from the process of letting the project become something. battling through the hurdles that are put in front of you is the part that I get my satisfaction from.

image by justin wu

DB: you have a number of colossal projects going on right now — I imagine there are quite a few challenges involved. is there a battle over steam rings right now?

BI: at the powerplant in copenhagen, yes — there is actually a whole new board and an interim CEO. even though we have the technical solution, we haven’t been able to present the solution to the board. we’ll just have to open the plant and open with a great success with no steam rings installed yet. unless something happens in its place, it’s not dead and it seems like it is hell-bent on coming back to life.

IG: some of these projects take ten, fifteen years from the time you conceive them until you actually start constructing them.

DB: and this pavilion was only six months, correct?

BI: yes, we got the commission in mid-december and it had to open mid-june. one of the things I’ve been inspired by ian and westbank was that when I met ian he said that the reason vancouver looks the way it does is that he had his own concrete contractor so he could get a little bit experimental with the structure and the form — but he had to have a more classic facade because he didn’t yet have a facade company. then I understood that ian is not just a developer. he takes care of the marketing of the building, and he’s operating most of his buildings and restaurants. I think more and more, his buildings are run by himself. he supplies his own power. instead of just handing the condos or hotels to someone else, he is operating a lot of it himself. we are trying to do that ourselves now but on the design side. we call it BIG LEAP: landscaping engineering architecture production. we really want to do the whole thing.

IG: there is really so much overlap — where does the architect’s job stop and the landscape architect’s begin?

image by @big_builds

DB: you clearly have a lot of consideration for context in your projects, but would you say this one can sort of exist anywhere?

BI: it was originally actually shaped by the location of the trees on its site in kensington gardens. a tree’s roots roughly match the extent of its branches because it needs to drink the water which falls from the leaves. in that sense, when you have a tree, you can almost draw a circle around it the same size as its crown. in a way, the bulge in the middle of the pavilion and its two curves are actually shaped by the trees. but of course, if it was a straight line at both the top and bottom, it wouldn’t have any space and also it wouldn’t stand, it would fall. so by having these curves it becomes stable and it becomes spatial.

DB: did you always intend for this project to travel?

IG: when I first saw the serpentine in london — a couple hours before the opening event when the construction guys were still crawling around — I knew the idea of taking it on the road wasn’t just a passing fancy. now bringing it here in a more urban setting, I actually think it’s more interesting than having it sitting out in the middle of a park. there, it’s just a pavilion in a park, but here you’re creating a condition where it’s juxtaposed against these beautiful heritage buildings.

toronto’s anticipated king street west

image courtesy of bjarke ingels group

DB: you had mentioned the relationship of your projects to the context of heritage buildings, and your philosophy of not trying to match the urban fabric. can you expand on that?

BI: I think contextualism is not about mimicry. it’s not about sameness, it’s about response. in that sense, we’ve tried to respond to the context. one of the boring things about the contemporary modern city is that everything is so regulated that it becomes so regular — the streets are wide, there’s enough space to park. everything becomes a little bit unchallenging and uninteresting.

IG: I think the bottom line is that BIG’s response makes the heritage buildings more prominent, more embellished than they would be even on their own. you ultimately have three potential conditions: one is to do nothing and leave the heritage buildings as they are; another is to do a traditional building that the planning department wanted; and the other is to do what we are doing. there is no doubt that the third condition embellishes the heritage buildings way more than the other two. it’s kind of like you gift wrap them saying, ‘here these buildings are really nice!’ as opposed to hiding them.

DB: because you do consider the context and the people, particularly in the case of king street west, the project is not just a case of a contemporary object placed in that urban fabric…

BI: yes, also it has this sort of self-grown character. it would be like when you see some older buildings where nature has taken over, the vine has gotten a little bit too big. in this case because of the combination of the glass brick and the greenery it has a different feeling and it’s as if this sort of organic thing has grown out between and over the existing buildings. then I think it’s kind of fun even the way we told the story. from the beginning we were hell-bent on using a red brick or yellow brick. we tried a concrete brick, we tried stones in a brick format. finally we landed on the glass brick that gave it a certain luminosity and lightness. but still there was somehow this idea of the texture and modularity that a brick wall has.

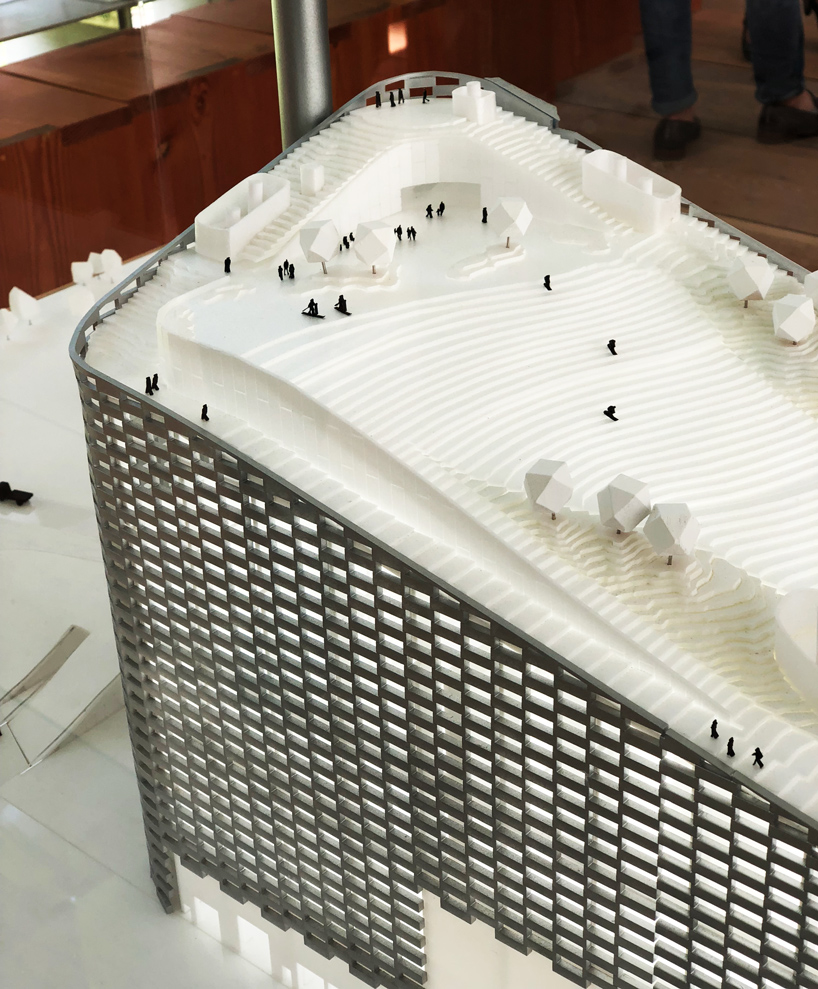

model detail of king street west

image © designboom

DB: I wanted to talk a bit about your early years. in architecture school today, there is a strong emphasis on digitally generated design and parametricism. in both design and fabrication there is an emphasis toward technology. what was your experience in school regarding the digital scene?

BI: I can tell you very specifically it was very limited. I started studying in 1993 because I wanted to become a cartoonist and the architecture school was part of the art academy. I thought it couldn’t hurt to spend a few years getting better at drawing backgrounds. when you draw a quick sketch you draw people and animals and vehicles — so I thought I could learn how to draw landscapes. the computer somehow happened. I moved to barcelona in ‘96, got my first computer there, and started working with it. when I graduated with my thesis project in 1999, I was one out of two in a school of a thousand students that submitted prints and not photocopies of mounted drawings. also I think I was the only one who used color.

DB: was it unfashionable to use color then?

BI: yeah, it was kind of a weird thing to do.

IG: at what point did you decide to abandon animation?

BI: I think it just happened, because it was not a conscious decision to let go of that dream but more that I became obsessed with architecture.

model detail of copenhagen power plant

image © designboom

DB: I have to ask, how was burning man?

BI: yes! it was my fourth year, and this time I brought two hundred fifty colleagues so it was a quite different experience and I think everyone had a blast. camp was amazing and I’m friends with some of the best chefs in copenhagen so we had amazing food and an amazing vibe. there was an amazing amount of programming around the orb — we had a sunrise concert under the orb, there was a ballet performance at sunset, there was sound healing, mind warriors did a massive group meditation at sunset under the orb. there are extreme weather conditions so we’re putting together a little film of all of the pictures that people have sent to us — I think we have around five hundred thousand pictures. there were so many situations where it looks like it’s from another planet, especially because it’s quite simple but also because it changed character — the first days it was very reflective. at night it was incredibly reflective but as it got more and more dusty — there was a huge dust storm — at some times it almost looked like a huge, floating piece of concrete.

DB: what became of ‘the orb’ — did someone ultimately take it?

BI: it’s still available. there’s been a lot of interest in it for various kinds of festivals.

IG: what’s it made of?

BI: basically, it’s made up of two layers — the inner layer is incredibly strong because to get it so pure it has to be inflated with a relatively high amount of pressure. the outer layer, they’re laminated together, is a completely reflective fabric that was used for NASA weather balloons. inside it’s held on a diagonal axis like a globe.

portrait of ian gillespie (left) and bjarke ingels (right)

image courtesy of unzipped toronto

DB: you have a very strong presence on social media. what do you think is the role of social media today?

IG: in order to get things done you need to be a great communicator. when you think about the challenges that we all have to get stuff done, you have to be able to bring people along with you in order to achieve what you’re doing. it’s a matter of finding a community of like-minded people that allow you to extend your opportunities where you would not otherwise.

BI: I totally agree and I think one fundamental aspect of architecture is that it is an art form that is so resource intensive. it requires so much collaboration and so much approval. if you’re a painter, you can make the painting and it can speak for itself. if you’re an architect, you have to speak on behalf of the building until eventually in six or seven years it can speak for itself. if you can’t defend it against all the obstacles it will surmount, it will die in its infancy. in that sense you have to transmit your conviction to others. secondly, in any field, whenever you do something it sends a signal. who knows who is going to hear it and who will respond to it. if you always have a clear message about what it is you’re interested in then the people who share that interest will hear it — ian was talking about finding like-minded people — those people will find you and they’ll have a much easier time finding you.