since starting her practice in 1990, indian architect anupama kundoo has built extensively in her home country with a strong focus on material research and experimentation. by learning from and collaborating with craftspeople, kundoo is heavily involved in the making process of a type of architecture that has low environmental impact and is appropriate to its context. kundoo’s work explores new ways of using age-old, local materials — combining traditional techniques with knowledge-based scientific systems.

with a monographic exhibition detailing the architect’s work currently on view the louisiana museum of modern art, designboom spoke with anupama kundoo to learn more about her introduction to architecture, her biggest influences, and how her outside interests impact and inform her work. read the interview in full below.

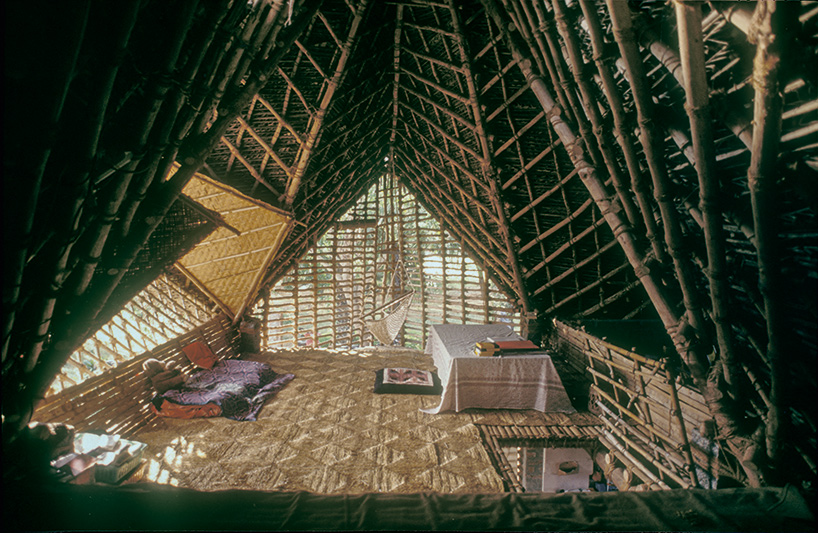

hut in petite ferme (1991), image by andreas deffner

designboom (DB): what originally made you want to study architecture?

anupama kundoo (AK): my mother, who had studied fine art, introduced us to drawing and painting at an early age and I did the intermediate grade drawing examinations alongside my regular school. apart from that, I was just into making things and creating things myself during my formative years, and took a keen interest in crafts, sculpture and knitting, as well as taking courses in tailoring. when I had to decide what to study at university, I was very torn between fine arts — especially sculpture — and mathematics, which was also a favourite subject.

hemant divya residence (1993), image by andreas deffner

AK (continued): in the indian context it was not possible to study both as these were considered to be in opposite directions, though for me they seemed perfectly compatible. an aptitude test suggested architecture, a profession I had not considered until then, given that I had no contact with people from the design world, but I immediately knew that this was for me and I never had a moment’s hesitation thereafter. having grown up in bombay, I felt that people deserved better spaces and a better habitat, and I was excited about the opportunity to contribute to this task.

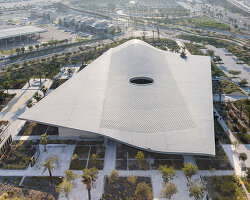

SAWCHU (2000), image by javier callejas

DB: what particular aspects of your background and upbringing have shaped your design principles and philosophies?

AK: my bengali parents moved to bombay when I was five, from pune where I was born. as our family was uprooted from its place of origin, so to speak, as many others affected by the political context of india’s freedom struggle, I grew up looking towards the great opportunity of the future, rather than romanticising the past. I was personally not the least interested in nostalgia. I was however rooted in the legacies of the past, but always felt the sense of freedom in imagining the future without the baggage of the past. I guess this has most significantly shaped my design principles and philosophy. I have grown up not being over-protected or urged to stay within the comfort zone. it has made me feel at home in the adventure of life, rather than seeking security in known habits.

wall house (2000), image by javier callejas

AK (continued): I think that attitude helped me to not fear experimentation but rather to relish it, as experiencing new frontiers made me feel enthusiastic and alive. to experiment is to feel alive, not only for architects, but I think experimentation is key to discovering and testing new ideas. in an ideal world, to be an architect is to be visionary. new ideas for the future call for new ways of implementation. experimentation is an integral part of shaping the future, as far as I am concerned.

wall house (2000), image by javier callejas

AK (continued): I have also absorbed core values from my parents and grandparents, and I see architecture as essentially a human-centric profession. I am concerned with users’ health, well-being and happiness, while I am also concerned with the livelihood that the making of architecture provides to people of a place. I am most concerned with the aspect of human scale in the built environment, and also in the processes involved in making architecture. above all, I think that beauty and poetry is what is needed to nourish the human soul, and everything we create should ideally be of a certain standard. future generations should be able to benefit from such environments and value their legacy, rather than having to make do with rapidly-constructed, commodified housing that is essentially profit-driven, for the enrichment of the few, ignoring the basic requirements for human well-being and our habitat, the earth.

creativity co-housing (2003), image by javier callejas

DB: who or what has been the biggest influence on your work?

AK: it goes back to the times before I began architecture studies, and even continues today. it’s still a lack of good design that stimulates my imagination, rather than the good designs I encounter and can simply appreciate. when one looks at our heritage of stepped wells and rock-cut architecture, fatehpur sikri, mandu and taj mahal, as well as old cities that were human-centric and well-crafted, contemporary manmade landscape seems so poor by comparison. this contrast triggers ideas and concepts in my mind that lead to architectural expression.

shah houses (2003), image by javier callejas (also lead image)

AK (continued): the early modern movement probably had the biggest impact on me in my formative years in architecture studies, for the sense of freedom it sought from the habitual ways of doing things. I was quite inspired by the bauhaus movement and the black mountain college for their sense of community and collaborative focus on radical experimentation. I admire charles and ray eames, le corbusier, antonin raymond, charles correa and kanvinde; but also those who worked with new engineering concepts, such as pier luigi nervi, frei otto, eladio dieste and buckminster fuller; as well as socially sensitive architects like laurie baker and ray meeker, whom I met personally. finally, after I moved to auroville I had the good fortune to collaborate with roger anger, auroville’s french chief architect and urbanist. he had by far the greatest influence on me, but not only through his ideas and visions. it was also his personality, his courage and integrity, and his attitude as an architect, and to life itself, that has been most inspiring.

mitra youth hostel (2005), image by javier callejas

DB: you work very closely with craftspeople. how important is this ‘hands on’ approach to architecture?

AK: it is not that I have been wilfully promoting ‘traditional’ crafts for their own sake. my early work in the rural indian context was the result of finding ways to ingeniously use what was locally available in terms of material, but also in terms of skills. with the larger socio-economic and environmental concerns in mind, I was keen to spend a larger proportion of the building budget on ‘labour’ rather than on ‘industrially purchased material’ that would need to be imported from far away. I do not have any kind of nostalgic attraction to indian craftsmanship, but I am concerned that the industrialised world of over-standardised solutions and corporate business culture are reducing the quality of life as well as the possibilities of creative expression.

townhall complex auroville (2005), image by javier callejas

AK (continued): I am more concerned about losing the human capacity to make things, rather than the loss of many ancient well-crafted objects. we are not yet fully aware of the implications on society when we no longer know how to do basic things with our hands, like sew a button back on. making has an impact on the mind and its evolution. making is a way of thinking and I am interested in prolonging the opportunity of thinking with the hands. so I find it interesting that if we resort to handmade technologies, we can build whatever we imagine, without any of the restrictions that machines carry, based on what they were designed to do.

volontariat home for homeless children (2008), image by javier callejas

AK (continued): also in the design process and in design education, I have found that hands on approaches help to demystify things, and unleash a lot of imagination, creativity and also a sense of empowerment, leaving people with more knowledge and confidence. if, as architects, we lose contact with ground realities, including contact to materials and real scale, we will make ourselves redundant, relying on our expert consultants as crutches, if we do not know the first principles ourselves.

volontariat home for homeless children (2008), image by javier callejas

DB: can the findings of your material investigations and experiments be applied to other geographic regions?

AK: I think that knowledge and investigations are always universal; it’s just the application and varying expressions that alter site-specifically. even if locally available materials differ, the universal laws such as gravity and engineering principles for the strength of materials, or climate engineering, remain the same. also, homo sapiens has a need for climatic comfort, light and air varying degrees of, privacy and community access, with small, contextual variations. if one interprets the role of the architect as merely reproducing buildings according to material catalogues and habits and trends in building culture, then yes, those habits are not suitable in other geographic regions as they would not necessarily be appropriate to the climate, local materials and culture. however if the practice is based on research and investigations, then the strategies and knowledge accumulated over the years will leave the architectural team more experienced and more capable.

kanade residence (2013), image by javier callejas

DB: can you tell us more about your co-housing project in auroville? how does it compare to your other work in the city?

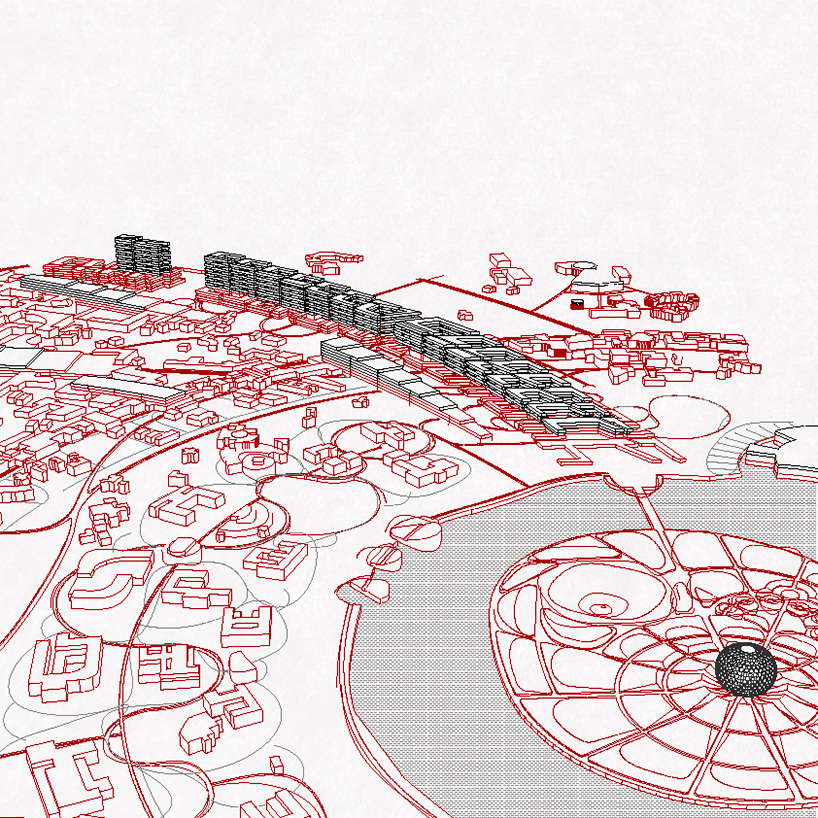

AK: planned as an urban project of co-housing clusters, the ‘line of goodwill’ is the first high-density, compact housing envisaged for auroville. 50 years after the city’s foundation, it can now take a bold urban step towards realisation of the compact pedestrian city planned by its chief architect, roger anger. to compensate for the areas of low-rise housing in the city and still achieve the required compactness and density, anger introduced urban structures that he called lignes de force meaning ‘lines of strength’. these extremely long porous structures rise tall above the rest of the city at one end, and gradually slope down over the entire length to reach the ground at its other end. in the residential zone, the towering heights are located towards the periphery of the city, their terraces facing the city centre. these structures enhance the dynamic spiralling movement of the town plan and absorb density with a minimum of circulation on the ground through vertical development. the cluster of buildings stretching over 800 metres starts at the entrance to the city, as a gateway for visitors, including hotel facilities with an 18-storey height toward the city limits, radially descending towards the city centre and reaching the edge of the central lake. the plan accommodates 8,000 inhabitants and includes the first steps towards a public transportation system. the large scale of the project allows radical and integral rethinking of habitat in the context of non-ownership of land, including social, environmental and economic aspects.

line of goodwill (2020), image by anupama kundoo architects

AK (continued): my other projects in auroville focussed on individual buildings as smaller neighbourhood clusters, while this project is an urban project proposal that is an extension of the work I did in collaboration with roger anger, on the city level. to fulfil its aim and purpose, auroville must realise its urban dimension so that there is the critical mass needed to rethink the economy, education and habitat as a whole, so that it can serve as a prototype for other cities.

unbound, the library of lost books (2014), image by javier callejas

AK (continued): the process has been different too and includes the idea of co-creation, incorporating inter-disciplinary collaboration as well as inputs from academia. students from various architectural schools have participated, including the university of stuttgart, the school of architecture of the academy of fine arts in copenhagen, the yale school of architecture in new haven and the fachhochschule in potsdam.

samskara (2014), image by anshika varma

DB: how would you describe the current architecture scene in india?

AK: countries like india are facing rapid urbanisation, with existing cities expanding endlessly and so rapidly that there seems to be no time to plan effectively. they are increasingly becoming unaffordable and unliveable and, as the developments are mostly developer driven, the new apartment towers are usually not connected through public transport and pedestrian or bicycle paths. the urban infrastructure and public spaces are not developed in advance, but usually added later on, if at all.

fullfill home in auroville (2015), image by javier callejas

AK (continued): there are many schools of architecture sprouting to match the pace, but there is no short cut to building knowledge and building a sensitive practice. in the context of commodified housing, and corporate practices, the smaller studios of good architects are often left with individualised houses and interior design projects. there is a great opportunity in the rapidly urbanising indian landscapes for architects, but there is a challenge in creating a larger context of planning and urban design to facilitate the realisation of better habitats.

nandalal library (2018), image by javier callejas

DB: what do you think is the role of an architect working today?

AK: I think that the role of an architect is the same as it has always been: to envision human habitation and shape the built environment in a way that can accommodate society’s evolving needs. the spaces created need to prioritise people’s well-being and health, individually and collectively. however, as the materiality of contemporary architecture raises many concerns, triggering environmental, social and economic imbalances, I think this area requires radical rethinking. this is particularly true of countries that have not seen mainstream industrialisation, yet have begun importing building trends from developed countries, adopting expensive construction models that require huge amounts of energy to function. if these standards of consumption become globally accepted standards, where local labour cannot participate and large construction firms source industrial elements and assemble them, then apart from a huge loss of quality of architecture, social segregation due to affordability must follow.

sharana daycare (2019), image by javier callejas

DB: outside of architecture, what are you currently interested in and how is it influencing your designs?

AK: I have many other interests, apart from architecture that have constantly influenced my work. I am interested in poetry, philosophy, art, biology and now anthropology. these influence my designs as I see the multi-faceted and lasting impact that architecture has on people. biology helps me to understand all the various ways in which nature has solved almost every structural question through design. I discover with fascination the geometry and order embedded in the DNA of cells of living beings that unfold over time. I am currently rereading gaston bachelard’s ‘the poetics of space’. the unending quest for knowledge in various fields have inspired many new ideas and areas for experimentation. they also help us zoom out and see the big picture and contextualise our insignificance or possible relevance. above all, I am interested in the human potential and what we become through what we do or make.

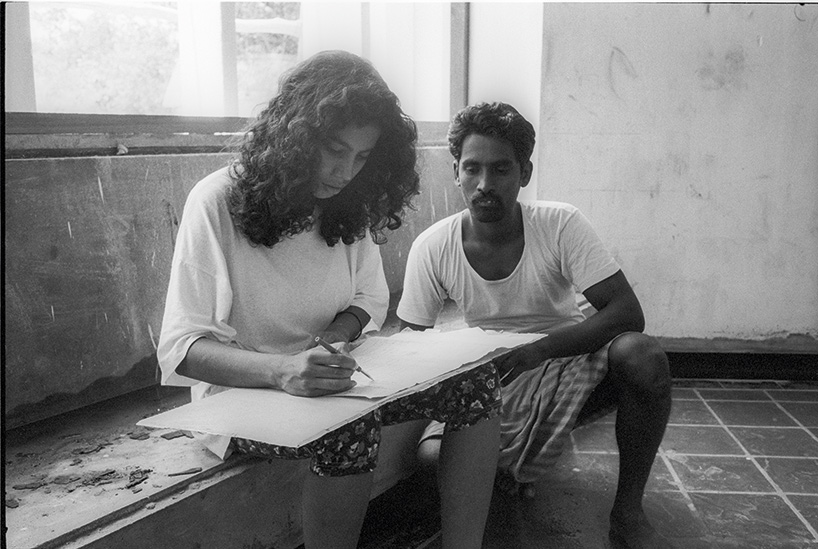

anupama kundoo in 1991 on the site of her first project, image by andreas deffner

DB: what is the best advice you have received, and what advice would you give to young architects and designers today?

AK: the best advice I received was that fear is not a good advisor. I urge the young architects and designers to step out of your comfort zone from time to time and challenge yourself. that will keep you young. do not underestimate the creative power of an individual, so do not follow trends blindly. think for yourself and do not submit to actions that you disagree with, fearing consequences. each action you make creates the tracks for your next action, and either imprisons you or empowers you. do not be discouraged; be patient, keep your aspirations and standards high. you will surely be rewarded!

anupama kundoo, image by andreas deffner

happening now! in an exclusive interview with designbooom, CMP design studio reveals the backstory of woven chair griante — a collection that celebrates twenty years of Pedrali’s establishment of its wooden division.