alfredo brillembourg photographed by boven lichtstreep

alfredo brillembourg was born in new york where he studied architecture at columbia university before undertaking his masters at the central university of venezuela. in 1993 he founded the Urban-Think Tank (U-TT) in caracas, venezuela – he was joined by hubert klumpner in 1998.

U-TT is a partnership committed to building and sustaining dialogue between stakeholders and policy makers. they use their work to explore design as a strategy for sustainable, urban development throughout the world.

for over twenty years brillembourg has also been a professor; at the university josé maria vargas, the university simon bolívar and the central university of venezuela and the graduate school of architecture and planning, columbia university, where he co-founded the sustainable living urban model laboratory (S.L.U.M. Lab) with hubert klumpner in 2007. alfredo and hubert are both currently professors of architecture and urban design at ETH zürich.

designboom: what’s the best moment of the day?

alfredo brillembourg: breakfast! no question about it.

DB: what kind of music are you listening to at the moment?

AB: david bowie, john cayle, a lot of blues… lots of different music.

DB: do you ever listen to the radio?

AB: yes all the time, especially in the car.

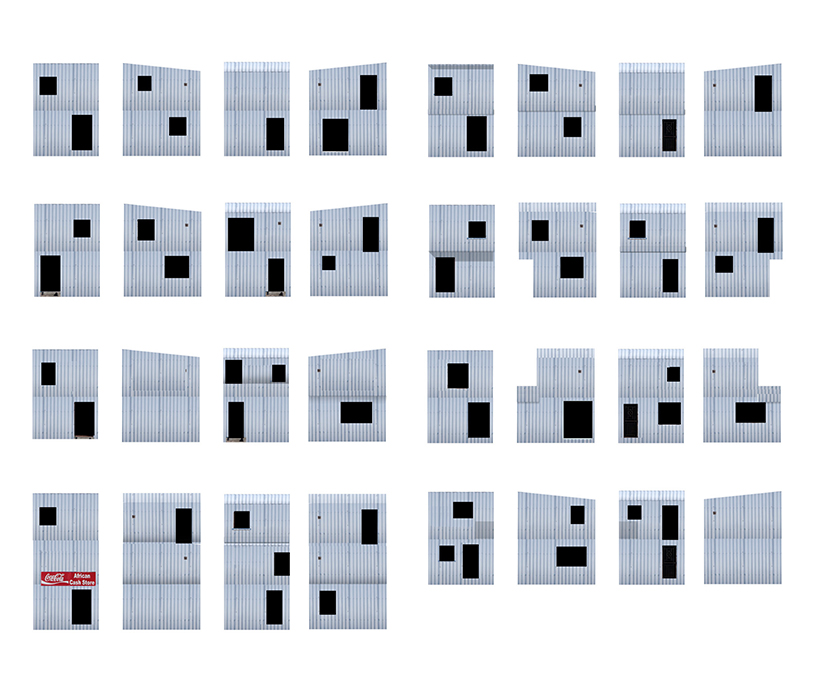

empower shack prototype, 2013 – ongoing

in partnership with ikhayalami (south african NGO) and swisspearl

around 1.5 million households in south africa (approximately 7.5 million people) live in 2,700 informal settlements scattered across the country, which faces an overall shortage of 2.5 million houses.

alfredo brillembourg and hubert klumpner, along with their research and design teams and collaborating partners are engaged in an ongoing project to develop and implement design innovations for rapid and incremental informal settlement upgrading.

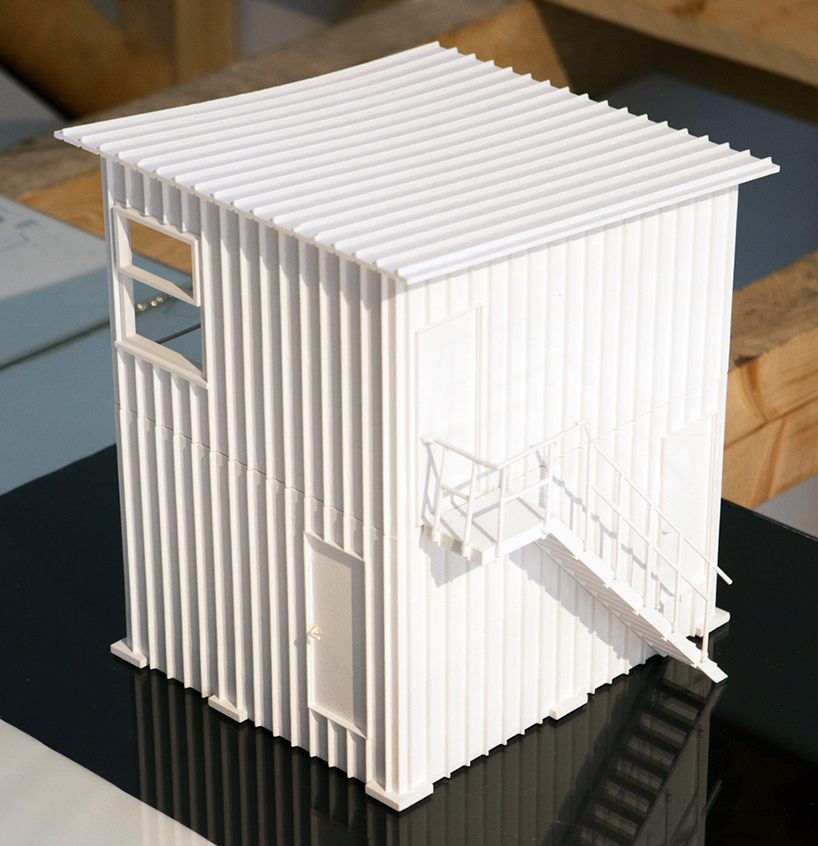

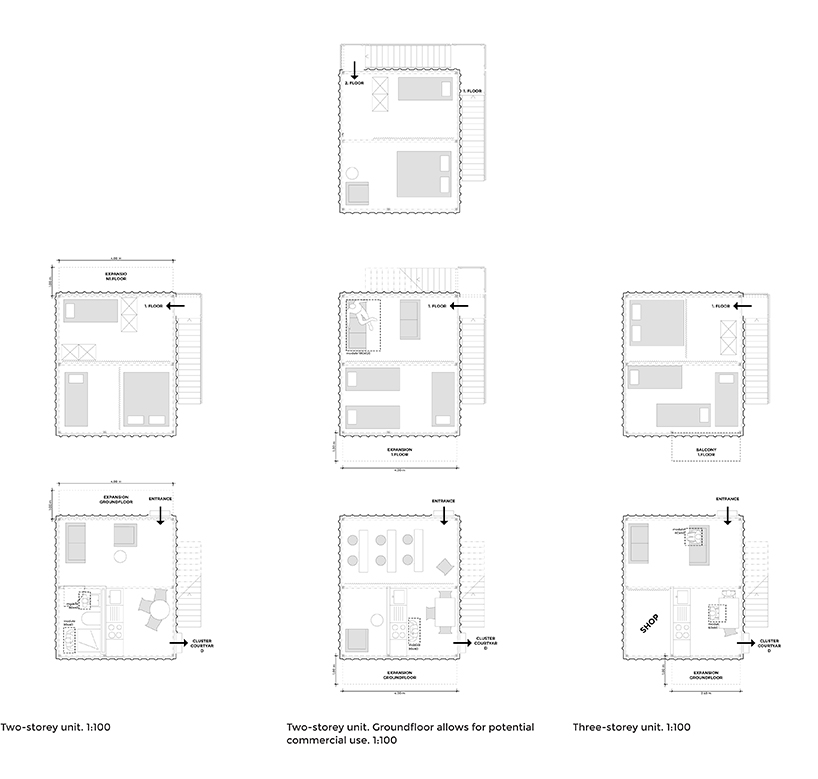

empower shack model – version 1.2

a clip lock cladding system is self supporting, adds bracing and is available in 40cm modules – suitable for the structure. openings can be made depending on the material availability and and the needs of the inhabitant. the owner is not dependent on a particular floor plan to determine the interface between public and private space.

various floor plans for a two storey unit

DB: do you ever buy design or architecture magazines?

AB: we receive them in the studio from time to time but I’m buying less and less of them.

DB: where do you get your news from?

AB: from the web mostly these days but I still enjoy looking through a physical newspaper at breakfast.

DB: I assume you notice how women dress, do you have any preference?

AB: exotically.

DB: is there any type of clothing that you avoid wearing?

AB: anything too tight.

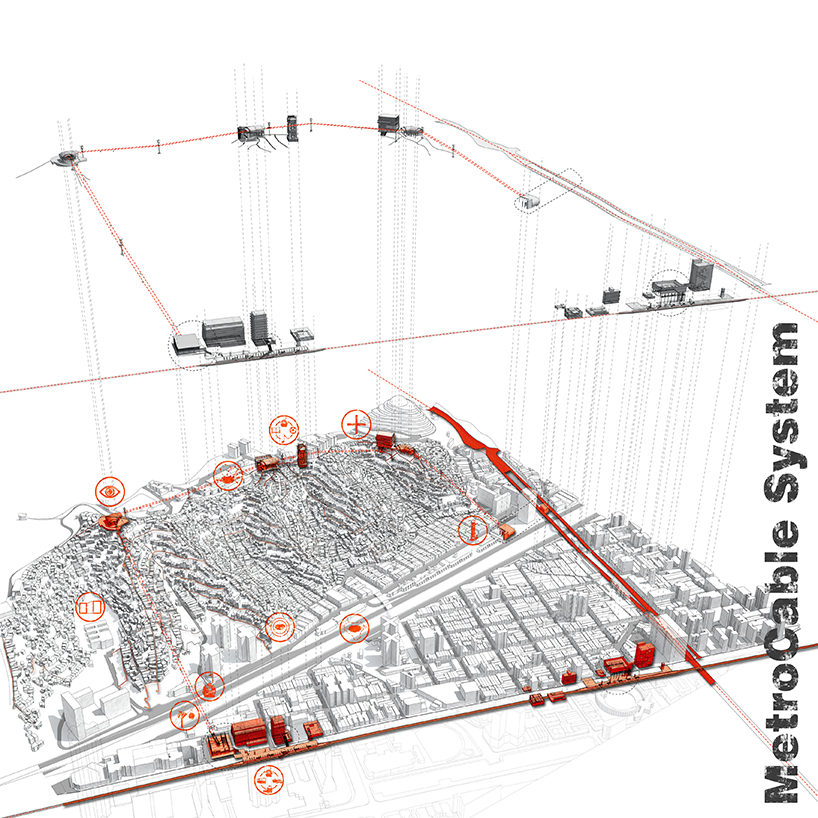

metro cable, san agustin, caracas, venezuela, 2007 – 2010

photo by iwan baan courtesy of urban-think tank

the cable car system, which is integrated with the metro system of caracas, is 2.1 km in length and employs gondolas holding 8 passengers each. metro cable’s capacity allows for the movement of 1,200 people per hour in each direction. two stations in the valley connect directly to the caracas public transportation system. three additional stations are located along the mountain ridge, on sites that meet the demands of community access, established pedestrian circulation patterns, and also spatial availability for construction, ensuring minimal demolition of existing housing.

photo by iwan baan courtesy of urban-think tank

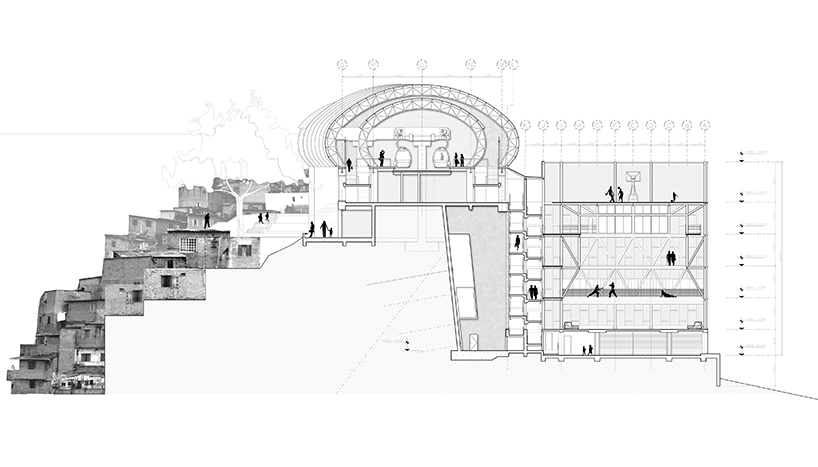

view of the main terminal

photo by daniel schwartz courtesy of urban-think tank

metro cable system diagram – the five stations’ designs share a basic set of components in common; platform levels, ramps for access, circulation patterns, materials, and structural elements. however, each station differs in configuration and additional functions, and the separate stations include cultural, social and system administrative functions; replacement of demolished residences with more homes, as well as public spaces; a gym, supermarket, and daycare center; and a link between the cable car system and the municipal bus circuit.

cross section of one of the main terminal

DB: when you were a child, did you always want to become an architect?

AB: no, I thought I’d become a film maker, then a writer, then a politician, then a businessman… I guess I combined all of those things when I became an architect. I wasn’t sure about becoming an architect in the beginning. it’s like meeting your girl – do you know for sure that you love her from the first day? but gradually you fall in love and what’s meant to be is meant to be.

DB: do you draw often?

AB: yes – almost constantly.

DB: do you think it’s still important for an architect to be able to draw?

AB: yes because the journey of a thought traveling from the mind, to the hand, out through the pencil onto the page is a very important translation process. I especially like to draw with pencil on paper because the paper is absorbing your thoughts in a way while the computer screen is beaming information back at you constantly. my advice is start with a piece of paper and a pencil.

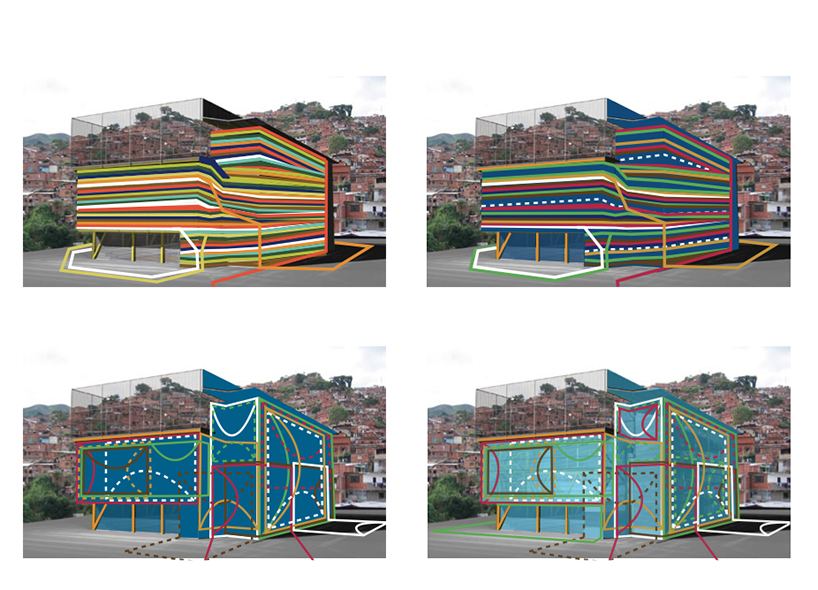

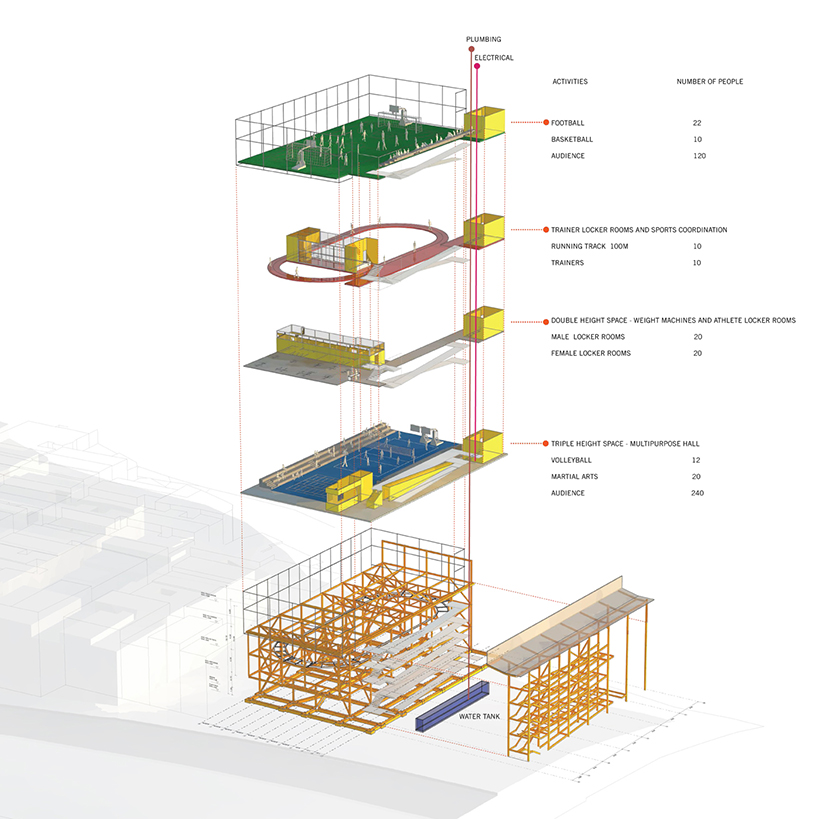

vertical gym 1, caracas, venezuela, 2004 (full project credits)

when a kid with a basketball and a dream becomes another victim of barrio crossfire, something has to be done. we cannot stop the purchasing, selling, and firing of bullets. but we can create novel spaces, nurturing values such as fair play, tolerance, and civic community; where youths measure up one another in sportive competition rather than in violent street fights. the vertical gymnasium at barrio la cruz (bello campo), constructed over 1,000 m2, transforms the site of a former makeshift soccer field into a fitness complex with basketball courts, a dance studio, weights, a running track, a rock-climbing wall and an open-air soccer field—an integral leisure facility for this densely populated sector of the city.

visualizations of the exterior – the first of its kind, this vertical gymnasium bustles with activity day and night, and welcomes an average of 15,000 visitors per month. crucially, it has helped lower the crime rate in this barrio by more than 30 percent since its inauguration.

when buildings in the informal city attain a limit for horizontal expansion, further building activity continues vertically. residential buildings and office structures have always developed this way, yet municipal planners continue to plot sports facilities on a flat map, rendering leisure and recreation unfeasible in settings where surface area is lacking.

aerial view of the site for the first vertical gym

interior – photo by iwan baan courtesy of urban-think tank

interior

photo by daniel schwartz courtesy of urban-think tank

DB: where do you typically work on your projects?

AB: anywhere I can really; at my desk, hotel rooms, planes, boats, in the car.

DB: do you discuss your work with architects outside your studio?

AB: all the time. I’m a very insecure architect in that respect because I’m asking people all the time what they think about our work. I like to bounce ideas around with people from all walks of life – but you’ve also got to be careful who you listen to!

DB: how would you describe your style to someone unfamiliar with your work?

AB: we’re interested in informal frameworks; it’s rough and tough, quick and cheap.

DB: can you see an evolution in your work from your first projects until those of today?

AB: in terms of scale and ambition the projects have grown gradually over the years from small investigations with artists – to public buildings – to urban planning.

DB: which project have given you the most satisfaction?

AB: the vertical gym, it’s proven very popular and effective.

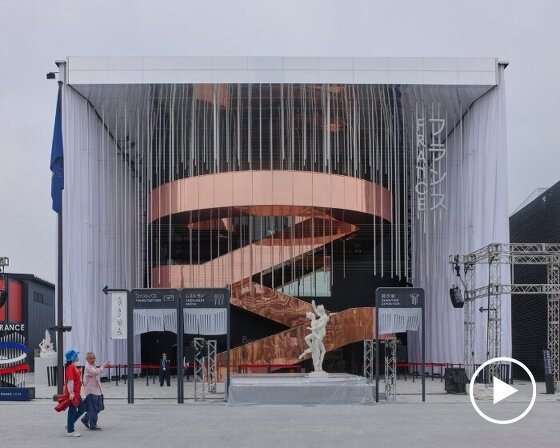

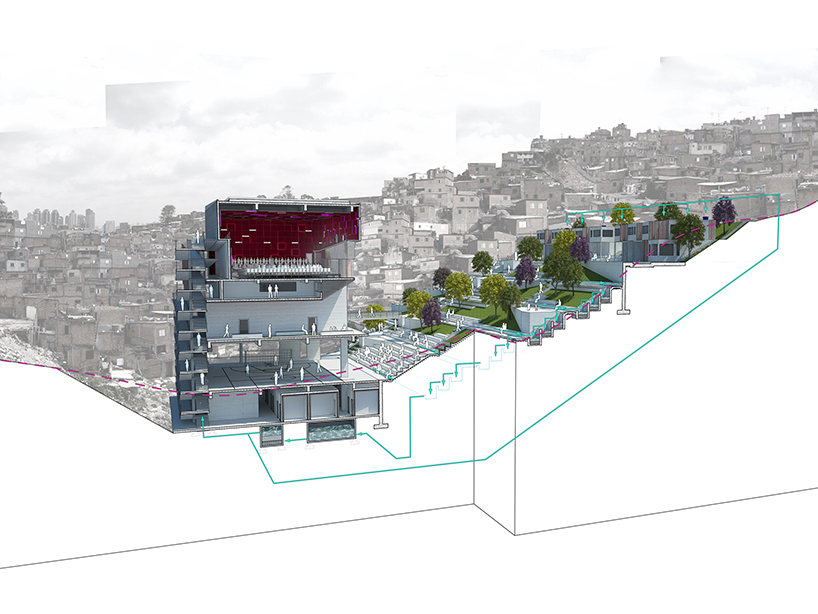

grotao community center, sao paulo, brazil, 2010-14 (full project credits)

in the grotao community center and park, our priority is equipping this peripheral neighborhood with infrastructure, water, sewage networks, lighting, services, and public space. the proposed urban model aims to translate a society’s need for equal access to housing, employment, technology, services, education, and resources—fundamental rights for all city dwellers—into spatial solutions. despite its central and urban location, the area of grotao is connected with only one road to the larger circulation systems of sao paulo, effectively separating it from the formal city. within this separated zone, increased erosion and dangerous mudslides have characterized the site as one of many low-access and high-risk zones. as a result, the unfortunate but necessary removal of several damaged housing units has created a void in the otherwise dense fabric.

the site contains the music school prototype, which vertically stacks several diverse programs to maximize site potential. these include the bus station/transportation infrastructure, soccer pitch, community center, and the music school, which contains classrooms, practice rooms, recording studios, and performance halls. this new facility, essentially a musical education factory, is a vital catalyst in this area, expanding music programs into the favelas while beginning to form a new network that serves the youth from all levels of society.

commercial spaces are also introduced on the first level as an economic vehicle that activates the street level. the upper zone contains new replacement housing for those displaced from high-risk zones. the building maintains both physical and visual connections within the area through a large, open level that works as a continuation of the terrace system.

DB: what would your ideal brief be?

AB: our dream project is to develop we call the ‘toolbox’, which is a kit of open source urban solutions that are related to social design, healthcare, recreation, culture and mobility. the idea is that the toolbox would function almost like an IKEA catalog for governments, so that they could implement proven design solutions in their cities and get them on track and thriving again quickly without worrying about budgets, time frames, construction and so on.

DB: which architects do you admire the work of?

AB: many, particularly a lot from the 1960s and 70s. to name but a few I’d say alison and peter smithson, aldo van eyck, ant farm, 999 – these are all people or studios that are able to get experimental architecture built, and that’s an important skill to have as an architect.

DB: do you have any advice on how to convince a client of your ideas?

AB: take them by the hand and show them what you think the solution is, go with them to the site and explain why things are important. many clients have power and money or both but they might not be familiar with architecture on a level that they need to be to understand what will be the best solution for them. don’t shy away from that challenge and be happy simply to repeat existing commercial formulas just because it’s the easiest thing to do.

U-TT founders: hubert klumpner and alfredo brillembourg

DB: what advice would you give to young architects?

AB: make a collective. share knowledge act like lawyers and doctors do; refer people and projects to one another, consult with one another when someone else might know best. since we started the urban think tank well over a hundred people have passed through and many are still connected to us in one way or another, sharing information, writing about their experiences from all over the world. you can accomplish more and better things as a collective.

DB: what are you concerned about regarding the future?

AB: that architects become too frivolous. there’s a lot of places around the world that need the attention of talented architects. I hope we realize this before becoming too self indulgent.