after more than a decade of close collaboration, ilmari lahdelma and rainer mahlamäki founded lahdelma & mahlamäki architects in 1997. now, more than 20 years later, the company has grown to a team of over 30 employees. based in helsinki, the firm’s work focuses on sustainability, high-quality materials, and attention to detail — qualities synonymous with the best of finnish architectural design.

with the firm recently celebrating its 20th anniversary, and with a host of new projects — and a new website — to discuss, designboom spoke with ilmari lahdelma and rainer mahlamäki to learn more about the duo’s creative collaboration. read the interview in full below.

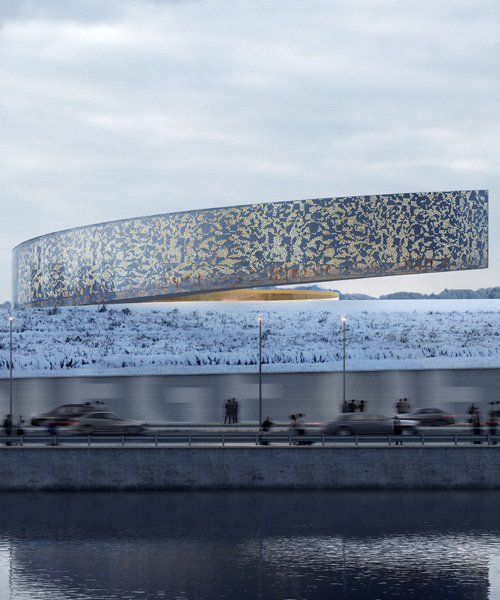

the finnish forest museum, lusto | image by jussi tiainen

designboom (DB): lahdelma & mahlamäki architects was founded in 1997. what were the firm’s original intentions, and how has the practice developed over the last two decades?

ilmari lahdelma (IL): our studio today you could say is simply an evolution of our working partnership, from when we first came together as students at the university of tampere — finland’s second largest city — long before 1997 as a loose collective that we named ‘8 studio’.

rainer mahlamäki (RM): we have to start by saying that in finland a huge importance is put on architectural competitions, especially as a tool for younger architects to breakthrough into the spotlight. so, naturally in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s we were producing a large number of successful competitions, locally high-profile ones such as the master plan to redevelop tampere’s post-industrial finlayson factory area. things went well, but it wasn’t until we moved to helsinki with our friend mikko kaira to form kaira-lahdelma-mahlamäki that we hit gold with our first competition-based public commission, for the finnish forest museum, lusto, in eastern finland.

IL: since then we have still remained heavily involved in design competitions, both at home and internationally; and as jurors as well, not only competitors. we believe in the mentality of the competition, to give a fair advantage to every participant but also to generate and explore new ideas and responses. we both still spend a large part of our time sketching just like we always have — only today we also back it up with our hugely capable team, technologies like virtual reality and a constantly updated understanding.

the finnish forest museum, lusto | image by jussi tiainen

DB: you have completed a number of very successful museums. do you feel that your firm is particularly suited to these types of projects, and, if so, why do you think that is?

IL: yes, museums are one of our greatest loves. but we can say that it’s more than just museums, but in general buildings with a public core to them. this could be museums, galleries, schools, public libraries…

RM: that’s very true. it’s all a result of the way that we approach design; for us, each project is its own thesis. we have to really deeply understand the site, the current situation and the people that the building affects. it might sound like the usual narrative, but there is a sense of humanism in finnish modernism (from the likes of aalto or saarinen) that we take inspiration from that is particularly suited to public projects — museums that immerse visitors or schools that create curious students. to implement this, you truly have to understand what you’re working with. in our museums you can really see the human scale, tactile surfaces and overall modesty — maybe things that come as a result of our nordic heritage. this way of working gives you the option to present an idea through atmosphere and physical touch rather than just exhibitions.

proposal for the UK holocaust memorial, london | image by brick visual

DB: in a similar vein, what are the challenges involved when designing schemes that deal with memory or loss?

RM: one of the bigger issues that we always have to keep in mind is the responsibility on us of correct representation. that is to say, we have to be careful that our designs and exhibitions remain true to what actually happened; and this is something that we try (as much as one really can) to understand the subject, talk to the relevant people and get our facts straight; then with the help of our experience, turn this into an understandable architecture.

another big concern with these projects is also to design appropriately. by this I mean that the museum or memorial often shouldn’t be a selfish shining object in the city, it also shouldn’t fixate the city in the past and center it on that one particular event, theme or tragedy. it should, more often than not, be a modest but elegant reminder of the past, which is representative of the city surroundings as they are today, and that optimistically looks towards a brighter future.

proposal for the UK holocaust memorial, london | image by tegmark

read more about the project on designboom here

DB: you are also working on many educational projects. what is your firm’s approach to designing schools for students of various ages?

IL: in finland we are fortunate to have a very forward thinking educational system, with really innovative people working to develop it. it is a system that is centered around people, young and old, that puts the student and community at the center of everything — people not profit. so, naturally, what we do is to engage with these people. we dedicate time to talk to people who live in the community, the teachers that will work there, the students themselves. there’s no avoiding it, and that’s a great thing.

kastelli school and community center up north in oulu was the perfect example. this is a project with a huge program that naturally had people worried at the start. it had three schools, huge sports facilities, adult learning, after-school community space and much more. but we talked to students, teachers, the community and worked out the best way to integrate everything. we adjusted the traditional classroom to be more physically flexible and use space outside of the classrooms for mixed-age and mixed-subject learning. at the heart of it, we learnt that learning happens in more ways than just sitting at a desk facing forwards. it’s not us that determine the teaching methods, but it is our role to design spaces that offer the possibility for any type of learning to take place, now and in the future.

kastelli school features flexible learning spaces outside of the classroom | image by kuvio

DB: do you find there are similarities between designing museums and schools? can you approach them with a similar methodology?

IL: absolutely, yes. both museums and schools, in the way that we design them, are very similar buildings. on one hand, the museum is a learning institute. on the other a school can also be a cultural center. either way, both should have very public cores to them.

RM: the essential question is how we communicate institutional and cultural identity of these buildings. how can the identity and purpose of the museum or school be represented through architectural means? first there are the similar functions: learning rooms, libraries, assembly rooms, gallery space, auditoriums, spaces for public congregation. then there are the ideological similarities, the fact that the building is representation of the local community, maybe even their cultural epicenter for the years to come.

the POLIN museum is located in warsaw, poland | image by iñigo bujedo-aguirre

read more about the project on designboom here

IL: one way to look at both schools and museums is on an urban or community level. in both the answer is always unique to that project. how does the building relate to its surroundings, bring the community in and fit in the city? this then gives way to form. in POLIN, in warsaw, the great chasm through the building connects the public park to an existing memorial to the heroes of the ghetto uprising; the exterior remained elegant but modest. heinola school, in finland, is built to draw the community into the building. it’s open and landscaped on all sides and has a very open central space that is designed to be flexible, adjustable, to hold all kinds of community events.

of course, the subject matter and the focus of museums and schools can very different, but indeed one school can also be hugely different from the next. the way to look at is that the method of designing — the learning, putting the jigsaw puzzle pieces together, understanding the people, the site — is always the same.

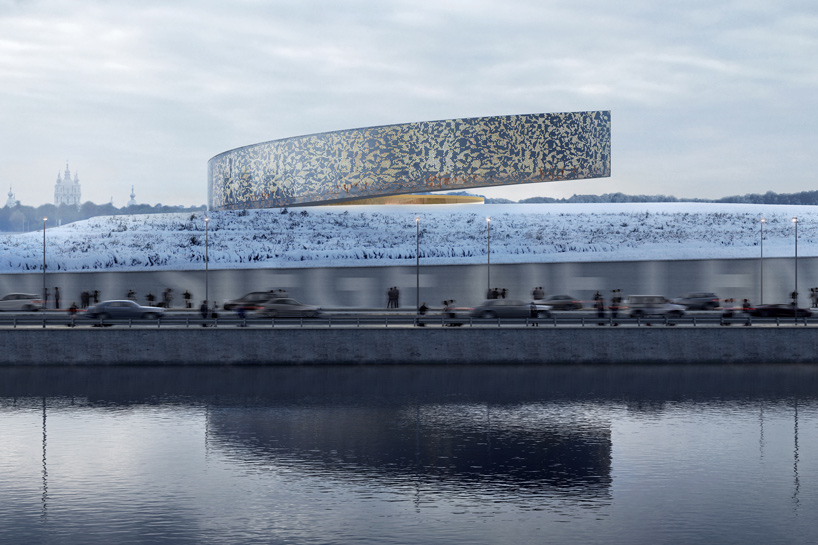

the firm’s spiraling proposal for saint petersburg’s siege of leningrad museum | image by brick visual

read more about the project on designboom here

DB: what projects are you currently excited to be working on?

RM: it’s a busy time for us in the studio with many really exciting things to work on. we have the lost shtetl in seduva, lithuana. the museum tells the stories of the small town where all of the jewish people were killed in 1941. physically, it is a modest sized project but symbolically it is huge; a big step for lithuania with regards to remembering the terrible events and the lives lost.

IL: we are also nearing completion on the first phase of a campus that we’re designing for the metropolia university in helsinki. in this one we’re combining a many very different functions, everything from surgical rooms to a factory for pre-cast concrete elements. when it’s completed, this will become a fantastic, lively, center of knowledge and activity.

RM: then there are also the many competitions that we’re working on, at home and internationally. of course, there is also the helsinki high-rise competition that we have just won. so it looks like the coming years are going to be really exciting for us.

the first phase of the metropolia university campus is nearing completion in helsinki

DB: how do you feel your backgrounds and upbringings have shaped your design principles and philosophies?

IL: our pasts are still very relevant to our work today. everything we’ve learnt we’ve tried to carry with us and you can almost spot the path of our work going back to our projects in tampere. in these early days, the ‘70s and ‘80s, architecture around us was constantly being re-assessed — and we played an active part in that rethinking, we absorbed a lot.

RM: considering the time in which we were learning, we were heavily influenced by a generation of great finnish modernists. this is inescapable in finland, especially as an architect, but they created an architecture that was so understandable to people here, so relevant. the influences from finnish nature come straight through their work, something which translates into a very relatable human scale; alvar aalto’s door handles for example are a masterpiece.

IL: coming as the generation after them, their influence on our work was enormous. but at the same time we are also functionalists — we are obsessed with details, tectonic systems, materials, structures… the finnish climate is unforgiving and much of what we design originally comes as a way to make this easier to live with.

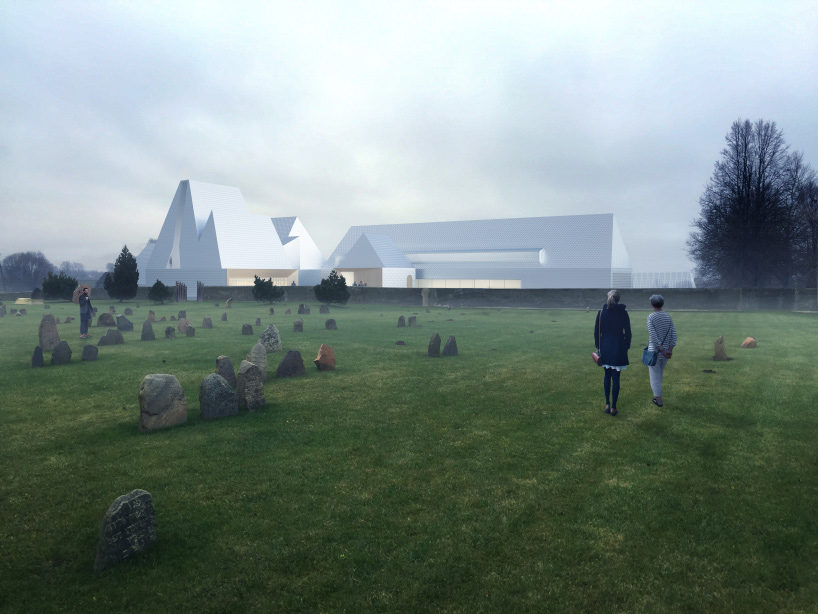

the lost shtetl is a lithuanian jewish culture and heritage project

DB: what do you feel are the biggest challenges for architects working today? are you optimistic about the future of the profession?

IL: we have immense respect for our older colleagues and for the strengths of their thought and work, and we are equally stimulated and encouraged by the younger architects now gaining commissions and prominence (many of them have been our students!). for us, having had such a long period of designing, teaching, administrative leadership and professional service — it is extremely positive to see how far finnish architecture has come and that the future of it seems incredibly bright.

RM: certainly for us, and our finnish colleagues, doors are beginning to open to international commissions outside of finland. slowly but surely progress is being made; we certainly are all pushing for it to happen. these possibilities, these commissions abroad, are extremely important for us, for our colleagues, and really for the health of architecture in finland. it’s about time that finnish architecture has more prominence internationally and that in turn we get more exposure to the outside world. already some incredibly exciting ideas are coming out; I just look forward to seeing how far it can go.

lahdelma & mahlamäki are working on a series of high-rise towers in helsinki

image by brick visual

DB: what is the role of an architect in today’s society?

IL: I think our role today is the same as it has always been. architects have always had this huge knowledge-base which has given us the duty to solve larger issues in society. through good architecture there has always been the power to show opportunities and to influence others. there are a lot more roles in the world today, but we have always been best at making an influence through our own work, through architecture. there is a power in that.

RM: yes, you can also say though that the role has changed in the way that we are now connected to people more. before, architects were seen as this elite group, a privileged group of thinkers. nowadays I believe, generally, we are far more connected to real society. there are many more of us and we are more like workers than elites. our status, you could say, has dropped slightly, but maybe that’s a good thing for us to sometimes stay relevant, grounded.

rainer mahlamäki and ilmari lahdelma

image by agency leroy

happening now! with sensiterre, florim and matteo thun explore the architectural potential of one of the oldest materials—clay—through a refined and tactile language.