herzog & de meuron revitalizes park avenue armory’s historic board of officers room

park avenue armory has completed the revitalization of its historic board of officers room, one of the few remaining designs by the herter brothers and one of the most important interiors in the country. the transformation turned it into a state-of-the-art salon for intimate performances and art installations. its completion is a major milestone in the armory’s ongoing $200-million dollar renovation project led by herzog & de meuron. the updated board room is a seamless marriage of old and new, which reestablishes the grandeur of the original gilded age design and infuses it with a subtle contemporary sensibility.

herzog & de meuron have revitalized the interiors by interweaving contemporary elements and reinvigorating original design of one of the most important period rooms in america. (above): board of officer’s room just completed

herzog & de meuron have revitalized the interiors by interweaving contemporary elements and reinvigorating original design of one of the most important period rooms in america. (above): board of officer’s room just completed

all interior images © james ewing

one of eighteen period rooms to be found in the palatial park avenue armory, the board of officers was likened to a ‘royal apartment’ in 1880 when it first opened, but fell into disrepair due to negligence and water damage in the decades since. thanks to the exceptional vision of herzog & de meuron, the skills of expert conservators and artisans, and a $15-million gift from the thompson family foundation, the staggeringly beautiful room reopened to the public on september 29 for its inaugural performance by baritone christian gerhaher. the performance is the first in a series of recitals launching this fall that will allow audiences to experience chamber music in the room’s intimate salon setting.

detail of woodwork

images © james ewing

ceiling detail

images © james ewing

detail of mantel

images © james ewing

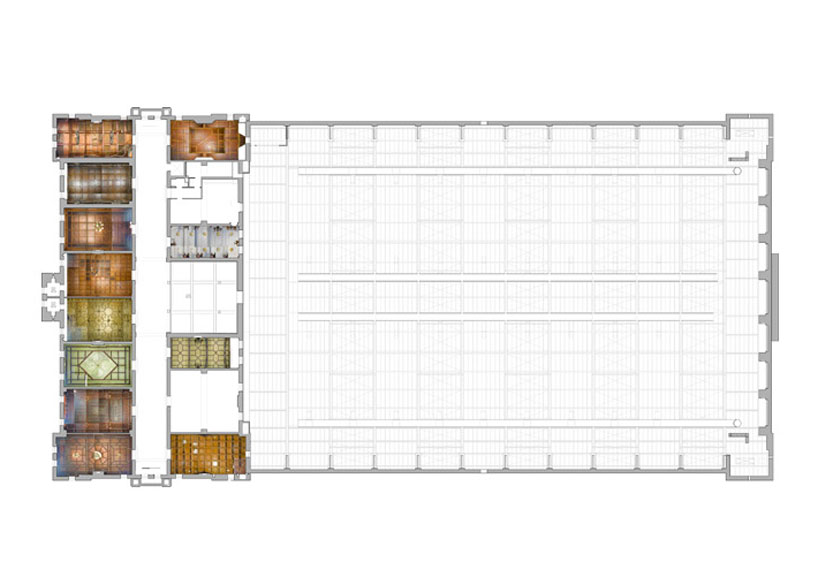

floor plan

floor plan

image © herzog & de meuron

section

section

image © herzog & de meuron

project info:

site area: 7,767sqm / 83,600sqft

building footprint: 6,596sqm / 71,000sqft

gross floor area: 17,652sqm / 190,000sqft

building:

constructed between 1877 and 1881, the park avenue armory’s 210,000-square-foot, five story building occupies an entire city block. the building includes:

the head house with eighteen historic rooms designed by louis comfort tiffany, stanford white, herter brothers, pottier & stymus, and other prominent designers of the late 19th century and the american aesthetic movement.

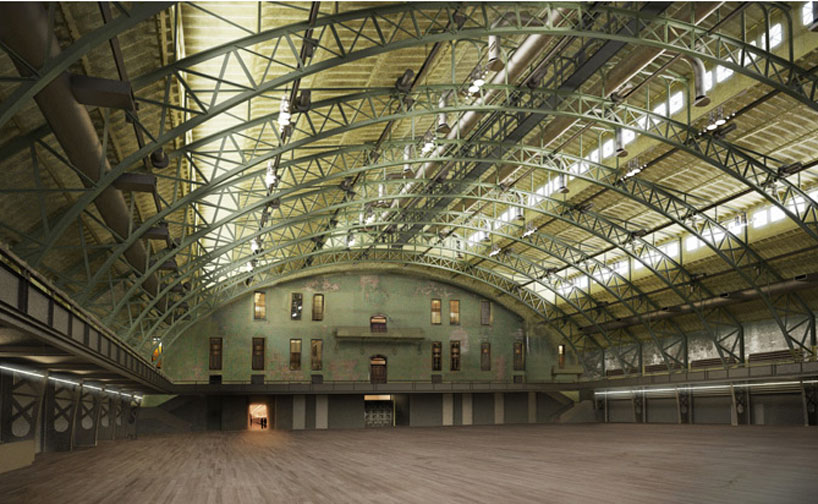

the 55,000-square-foot wade thompson drill hall, one of the largest unobstructed spaces in the city, which features:

an 85-foot-high barrel-vault ceiling (eight stories)

eleven elliptical wrought-iron arches

original georgia pine floors

8,000-square-foot rifle range located underneath the drill hall floor

PILOT ROOM company D completed in 2011

PILOT ROOM company D completed in 2011

statement from the architects:

When we first visited the Park Avenue Armory, it was full of the wiring left behind by emergency units set up there after 9/11. The historical rooms were still quite raw, often dusty and gloomy because they had not yet been cleaned up, but we instantly felt the historical weight of the structure and the importance of its social role in New York. Built between 1877 and 1881, the Armory consisted of a 55,000 square-foot drill hall covered by a balloon shed roof and wrought iron arch trusses – still one of the largest column-free interior spaces in New York City – adjoined to a castle-like head house filled with reception rooms and company locker rooms designed by the very finest artisans of their time, including Louis Comfort Tiffany, Stanford White, Herter Brothers, Pottier & Stymus, and other artists of the American Aesthetic Movement. But despite its outstanding historical significance, the Armory was suffering from severe damage and required intervention to preserve it as a monument for the future, while also reinventing it for new contemporary uses. This was when the Park Avenue Armory approached us to transform the interiors, originally built and converted over the years for regimental activities, into spaces for cultural activities ranging from studios for artists-in-residence to public performances to massive installations. We were immediately fascinated by the surprising combination of the gilded rooms inside the head house and the adjacent industrial drill hall, which we saw as found spaces, comparable to the former oil tanks and turbine hall that we transformed for exhibition purposes at Tate Modern.

Consultations with the client, artists, curators, and advisors confirmed that they all loved the spaces just as they were. They liked using the Armory precisely because its elaborate rooms were not white cubes and certainly not perfect stages. They wanted to work with the historical substance. We set ourselves the challenge of preparing the Armory for new functions with an updated infrastructure, while not only preserving its palpable sense of history, but enhancing it by revealing the physical traces produced over time. The preservation method often used for historical buildings in the United States is a ‘snapshot’; research is made into the historical original and it is recreated as closely as possible in a kind of simulative reconstruction. Our goal is neither such faithful reconstruction, nor the cultivation of an aesthetic contrast by juxtaposing the old with something radically new and different. Instead we work with the premise that signs of age and imperfection are not necessarily a flaw but of aesthetic value that may even bring out the beauty of the original. At first, we considered revealing all of the changes that had been made in a single room as a kind of palimpsest. We soon realized, however, that the rooms of the Armory each have a different identity, which is what makes the building so compelling: it is like an assemblage of individual characters.

Each historic room is very distinct and has to be treated individually. Every corner raises new questions with many nuances between reconstruction, restoration, renovation, and simulation.

Instead of one blanket approach, we enlist a variety of methods and techniques that overlap and that work differently in each of the rooms. What ties the project together is the application of a same three-step procedure in each room: first, delayer to the original state as much as possible; second, stabilize the room along with the damaged areas: and third, reinforce and refurbish the room so that it best retains its (original) character. This may mean overprinting a wall with an integrated tracery to unify a damaged surface, developing specific light fixtures or furnishings to bring back the volumetric character of a room, or reconstructing an element that has been lost using the syntax of a different material or technique. As a unifying element, we accentuated the metallic aspect of the Armory. Metallic paints were developed around 1880 and reveals show that they were used extensively throughout the building. Since metal oxidizes with time, the patterns and architectural details have dulled and their effects are no longer visible. We reintroduce these effects and find different ways of implementing them. Copper is used because it can be reflective or matte, has a rich color range from a light copper sheen to almost black, ages very gracefully, and can be a textile, a coating, or a metal. This diversity means that it can be very inconspicuous.

We started our surface investigations by carefully distinguishing between floor, woodwork, wall, frieze, cove, and ceiling. Our aim is to reveal the original layer of 1880 and, at the same time, preserve the raw atmosphere that struck us the first few times we visited. In the process of delayering surfaces, we ask ourselves what defines the character of the respective room with the aim of developing a specific treatment strategy for each surface. The Board of Officers Room was in deplorable condition. On the outer walls and in the corners of the ceiling, large areas of the paint had peeled away due to water damage, and extensive areas of the ceiling had been anchored to prevent further loss. By revealing original layers where possible and reinterpreting the original design in the damaged areas, we were able to reconstitute the 1880 decorative scheme. The 1932 wall decor was removed to reveal the original campaign. The damaged areas were filled with field color and the lost patterns were reinstated by means of integrated tracery.

In addition to the basic infrastructure improvements to meet today’s comfort and safety requirements, specific

upgrades were also incorporated to accommodate the Armory’s artistic programming. In the Board of Officers room, which will be used for recitals and small scale art performances, acoustic improvement was a primary goal achieved through a number of precise interventions including acoustic upgrades to doors and windows as well as the integration of production lighting. Company E will be used for visual and performing arts, which led to the addition of ceiling strong points and power sources to increase flexibility.

The interiors were originally illuminated by gaslight and extremely dark, so additional lighting is a key factor in

reinventing each room. Not only more light but also the placement of light fixtures and how they relate to the rest of the room are important factors in reviving a room’s character. Therefore we aim to reinstate chandeliers and light fixtures in scale and function, but translated into a contemporary idiom. In Company D, we wanted to highlight the central position of the 1880 chandelier as well as its organic character. Simple copper tubes are bundled, following the path of wiring, while new lamps added to the top, bottom, and sides relate to specific lighting functions. The result is a compact form that is comparable to the scrollwork of the original. Custom glass globes diffuse the light, lending it a subtle warmth reminiscent of gaslight. In the Board of Officers Room, as early as 1897, the gas lighting was replaced by electric chandeliers and wall brackets of forged iron, which are hung at a higher level and are weightier in effect than the original ones. The 1897 chandeliers and sconces were cleaned and fitted with contemporary light sources integrated in custom glass globes hung at the original levels.

In contrast to the explicit emphasis on surface in the rooms of the head house, the massive interior of the drill hall is pure structure and requires a different syntax. Since the program calls for a flexible space, we designed it as a gigantic stage and equipped it with a new infrastructure. The drill hall’s grand proportions will be reinforced by reducing it to the bare essentials.

Outside, we have basically taken the same three steps as we did inside: everything that has been added and is no longer necessary has been removed, like the fire escapes which are replaced with new internal stairs. The exterior has been repaired and any new elements that are required, like emergency exits and the roof, are executed in copper so as to blend in and be almost unnoticeable.

The Park Avenue Armory is a richly layered building of outstanding historical significance, transforming into a contemporary cultural center for New York City. We are treating the Armory like a living monument, preserving it for the future and above all reinventing it. Our method is not preservation in the traditional sense, where the original state of a building is reconstructed to simulate the historical original. Instead, we are enhancing its palpable sense of history by revealing the physical traces the building has produced over time and developing highly specific responses to each space.

Herzog & de Meuron, 2013