KEEP UP WITH OUR DAILY AND WEEKLY NEWSLETTERS

happening now! partnering with antonio citterio, AXOR presents three bathroom concepts that are not merely places of function, but destinations in themselves — sanctuaries of style, context, and personal expression.

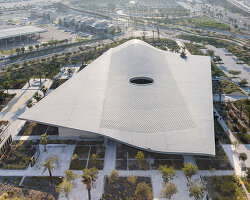

discover ten pavilion designs in the giardini della biennale, and the visionary architects that brought them to life.

connections: 20

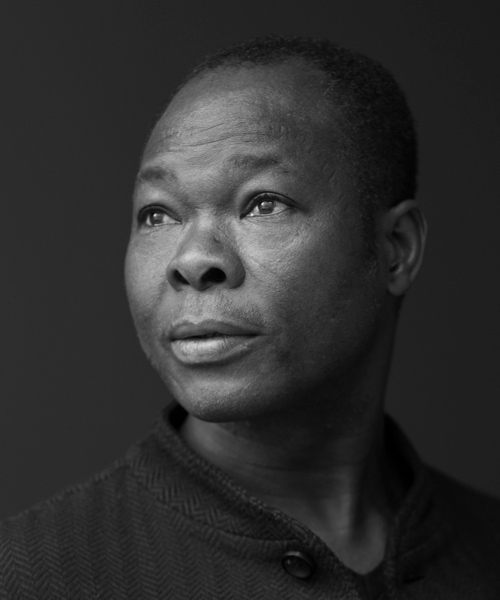

we meet carlo ratti in venice to talk about this year's theme, his curatorial approach, and architecture’s role in shaping our future.

discover all the important information around the 19th international architecture exhibition, as well as the must-see exhibitions and events around venice.

for his poetic architecture, MAD-founder ma yansong is listed in TIME100, placing him among global figures redefining culture and society.

connections: +170