recently knighted, sir david adjaye is widely recognized as one of the leading architects of his generation. born in tanzania to ghanaian parents, adjaye’s influences range from contemporary art, music, and science to african art forms and the civic life of cities. with a portfolio of work that spans pavilions and interior schemes to the monumental national museum of african american history and culture on washington’s national mall, adjaye has proven his ability to work with range of materials, scales, and locations.

at IDS 2017 in toronto — where the architect was the international guest of honor — designboom spoke with adjaye about the origin of his interest in architecture, the importance of geographical context, and some of the major projects he is currently working on.

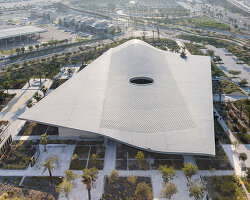

the national museum of african american history and culture / see more of the project on designboom here

image © alan karchmer

designboom: can you pinpoint the origin of your interest in architecture? when did you realize that this is what you were meant to do?

david adjaye: I know that it happened when I was doing an art foundation at middlesex university in london. I think it was halfway through the course when you had to sort of make a decision. you get to sample all the arts and then you have to start honing in. I suddenly realized that as much as I loved the arts, I wanted something with more social responsibility. I later realized that art could have social responsibility, I just wasn’t aware of it at that point. I felt that art was very introverted in its pursuit of knowledge and social impact, and I was not ready to be that kind of person. I wanted to be more engaged in the world.

inside the latest addition to washington DC’s national mall

image © alan karchmer

DB: how has your background and upbringing shaped the work you do now?

DA: I think you are always a product of what you do and where you came from — you are shaped by your background. I was very inspired by the world and the things that I saw, but what inspired me wasn’t the artifacts or the quality of architecture, but the power of architecture to shape societies. that was more powerful to me. then of course later, I found that profound structures have a way of shaping the way in which a society sees itself, and that became very important to me.

inside the aïshti foundation in the lebanese capital of beirut / see more of the project on designboom here

image © guillaume ziccarelli / aishti foundation

DB: what do you feel is your practice’s strongest skill, and how have you worked to develop that over the past years?

DA: I think that we are very interested in ‘crafting’ buildings — the physical craft of construction and the narrative behind the craft of making buildings. something else that we’re very interested in is not only trying to translate more than just the performance, efficiency and power of a thing, but also have a conversation about stories. what I mean by that is making construction perform to the geographical concerns and sociological impact of a place — to bring that to light. I’m interested in that because I truly believe that that starts to make architecture perform in a different way. it brings science and social agenda together. I’m interested in science and society coming together in architecture much more specifically.

‘sugar hill’ is a mixed-use development in harlem, new york / see more of the project on designboom here

image © wade zimmerman

DB: in that vein, what do you feel is the role of architecture on a humanitarian level?

DA: I don’t like the reductive nature in which architecture has been placed almost as an appliqué. I think we’re seeing the end game of what happens when you say that structure is simply science. if you let that happen, experts take over, because architects are consummate jacks of all trade and masters of none. I think an architect needs a large arsenal of opportunity under his portfolio to be able to affect the image of the construction industry. I think the architect needs to perform with a lot of these things under his agency, to complicate the story and to complicate the issue. so that’s it’s never simply a reductive strategy, it becomes critical to regain the architect’s power, and the ability to shape our built environment. I’m interested in the re-complication of that.

david adjaye’s ‘double zero’ chair for moroso / see more of the project on designboom here

david adjaye’s ‘double zero’ chair for moroso / see more of the project on designboom here

image by alessandro paderni / courtesy of moroso

DB: how important is it to change your approach as you work from country to country? how are you able to do that?

DA: it is critical. even though I think there’s a conceit in my own work, I also feel like I’m simply a product of the age. I don’t want to be a hedgehog and put my head in the sand, because I think hedgehogs are weird! I mean, what are you doing burrowing — be in the world! I want to be in the world. I think the global mission of the 20th century has unleashed a planetary agenda in the 21st century. we’ve moved from a global agenda to a planetary agenda.

we know how to build cities, and we know what cities are, but what we’re interested in now is the evolution of the city, and also the birth and explosion of new cities. I think that the lessons that an architect learns now become more valuable when they are able to test the nuances of the condition in many geographies. geography — I’m really speaking about it a lot. people think ‘this is an old word’, but it’s not an old word if you think about what geographers are talking about now — anthropological and social ideas, as well as a literal geographical strata. it’s about the densification of things and about how those things are alive at the same time.

adjaye’s crinkle-cut concrete interior for valextra at harrods / see more of the project on designboom here

image courtesy of valextra

DA (continued): I think that the ability to be able to test yourself in many conditions attunes if you have the ability to understand that you’re making architecture — no longer in a place, in a village, or a town, but for the planet. it’s not about regionalism, it’s past that or moving that forward. for me, it’s the architect’s responsibility to construct on the planet. you can do that in an isolated bubble, but then the ecology of the construction industry is utterly global. there is really no such thing as a local practice, even if you pretend there is. you are using things that are coming from around the world. in a way, I think there’s that planetary responsibility. that responsibility in its purest sense — if you want to be a purist — is about the experience of the difference.

gwangju river reading room by adjaye and taiye selasi / see more of the project on designboom here

image by kyungsub shin

DB: do you still feel like there is a place for sketching ideas, or designing things by hand?

DA: I draw all the time, and we make lots of models. we don’t do it for nostalgic reasons. a 3D virtual thing is fantastic for doing certain things, but actually in the end, the presence of a certain material has an impact on your senses. we’re sensory beings. we have a sort of multi-sensory apparatus, and that is how we simulate space. that relationship to materiality is something that computers can’t really give us. although you can try to simulate weight in virtual reality, you still can’t do it. the sense of moisture, or dampness, or dryness of a material still requires physicality.

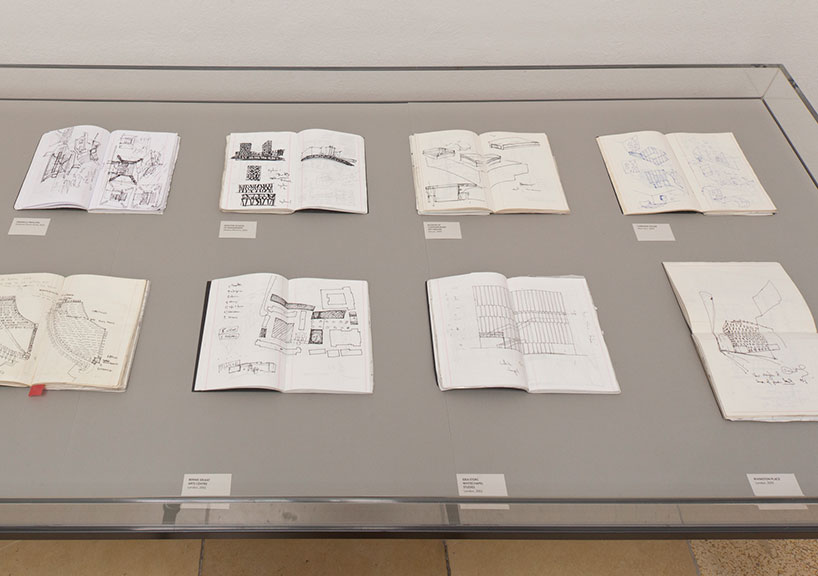

‘form, heft, material’ / see more of the exhibition on designboom here

image by doku petzi, courtesy of haus der kunst

DA (continued): the computer builds models, so to design in the computer is to know what you’re doing, or to find it in a systematic way. the conceptual way of thinking is to uncover what I call the ‘scrambled notes of the brain’ through the notations of the hand. the hand unscrambles the layers of information that are complexly laid on top of each other, and you’re unfiltering it. that act is something that the computer does not allow me to do. sketching is still the only thing that allows me to unpack the thoughts into a precise moment. for me, sketching is this unfiltering which no technologist has managed to do for me yet. sketching is essential. the computer requires me to know what I need to know, but first I need to unpack the thoughts.

sketches by david adjaye, presented as part of ‘form, heft, material’

image by doku petzi, courtesy of haus der kunst

DB: can you tell us about any projects that you are currently working on?

DA: we’re just about to start the new headquarters for the world bank in dakar, which is my first big commercial african building. we’ve been working with craftsman in mali, technologists in america, environmentalists in europe… I’m trying to put in place what I’ve been preaching, about this idea of a geographic spectrum, and how a thought can start to make these variations and mutations that also have the typological essence of what we’re talking about. for me, it’s ‘version 1’, and I’m very excited about that. it’s a very exciting project.

adjaye’s design for latvia’s contemporary art museum / see more of the project on designboom here

image courtesy of malcolm reading consultants

DA (continued): we’re also working on a project latvia, the contemporary art museum. latvia is the tiny country where rothko comes from, and for me that’s like the holy grail. I really wanted to make a building where one of the greatest 20th century painters came from, so making the contemporary art space for that country is an incredible honor. I’m really enjoying those two things.

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save