ball-nogues studio, led by benjamin ball and gaston nogues, is an integrated design and fabrication practice that works between the fields of architecture, art, and industrial design. based in los angeles, the duo first met as students at SCI-Arc, the southern california institute of architecture, before working within product design and set production until joining forces in 2005. their work explores the elements of crafting and the actual designing of the production processes for each project. the results create extraordinary and surreal environments that enhance sensation, generate spectacle, and encourages engagement. these qualities are highlighted in projects such as; ‘maximilian schell’ materials & applications exhibition space in LA, ‘pavillon speciale’ at the ecole speciale d’architecture in paris, and ‘air garden’ at the los angeles international airport.

following designboom’s studio visit and interview with benjamin ball and gaston nogues back in 2010, on a recent trip to los angeles, we caught up with the design duo to see their new studio, how their practice has evolved since we last spoke, and to hear what new projects they are working on.

looking down at the ball-nogues studio’s workspace from their office

image © designboom

(main image: pulp pavilion, coachella valley music and arts festival, 2015, image © joshua white)

situated on the edge of east downtown los angeles, in and amongst other manufacturing workshops and factories, ball-nogues studio truly blends in with its industrial habitat. their utilitarian space is an honest mixture of a second floor office that looks over an expansive workshop underneath. they moved from their old studio, which designboom visited back in 2010, to their new and much larger one over six years ago. their migration to LA’s boyle heights neighbourhood has become a common path in the city’s design scene as creatives and makers wish to be in close proximity to one another, to vendors, and be amongst the culture.

the workshop is full of materials from past, present and future projects

image © designboom

the studio lives and practices a romantic ideal between designing and making, where they constantly challenge materials in terms of function, aesthetics, and marketability. their workspace, which at the time was mostly taken up by the crafting of the ‘cabinet of obsolescence’ for fort dodge middle school in iowa, is a shine of their experimentation and the freedom in which they work. models made from a multitude of different materials are on display, such as the paper towers of the ‘pulp pavilion’, the crushed stainless steel blocks of the ‘secondhand geology’, and the bent steel tubes of the ‘healing’ pavilion, and are each embedded in a rich back story of trial and error. these objects remind benjamin and gaston of their studio’s past, their material knowledge, and how they strive to push boundaries further.

during our visit, they were constructing the framework of the cabinet of obsolesence

image © designboom

with a team of eight makers, designers and co-ordinators, the studio has a fine balance that benjamin and gaston oversee with logic. their fabrication experimenting, as awe-inspiring and innovative as it might be, is their financial responsibility. it almost stays as a hobby until they realize how it can actually enhance and strengthen a project. technology is a key component for these developments, but it doesn’t lead the way. seen as mundane if everyone is using it, ball-nogues tries to ensure that digitalization doesn’t take over their crafting – a quality that they feel has declined in the industry in recent years.

test models of the pulp pavilion can be seen in the background

image © designboom

after exploring round their office and workshop, and the many models and machines within, we sat down with benjamin ball and gaston nogues to find out more about their practice. furthermore, they provided great insight into their exciting upcoming projects, the differences between temporary and permanent work, and the current design scene in los angeles.

benjamin ball (left) and gaston nogues (right)

image © designboom

designboom (DB): could you give us some background about the studio and how you two first became a design duo?

gaston nogues (GN): we were at architecture school at the same time so we have known each other for quite a while. we took different paths afterward. we came back together in 2004 after we got together at a bar, of all places. we started talking about a project that ben was working on at materials & applications, it was a kind of golden vortex that we ended up calling ‘maximilian’s schell’. we decided to work on it together because we had complementary skills.

benjamin ball (BB): that project needed a team. an individual couldn’t do it alone; it needed a collective mind if it was to be successful. so I showed early models of it to gaston and he decided he to join me in moonlighting.

GN: that project established the method that we would employ for pretty much all our work afterward. we focused on material research, production methods and structure. we have explored those topics in all of our work. you see structure in our projects, it isn’t hidden.

BB: all of the projects are naked.

GN: exactly, the structure and connections are meant to be seen. it is what it is. we have always been really interested in this aspect and pushing the possibilities of it further.

BB: it is a decidedly modernist outlook but we are definitely not modernists. there is an old-fashioned aspect about that honesty toward materials and expression of connections. we realized that we shared values and we could advance a project by leapfrogging each other’s knowledge and experience. gaston is a kind of optimist and I am often pessimistic – these outlooks make for productive discussions during the process of developing a project. our views always seem to play off one another rather than cause disagreement. going back to ‘maximilian’s schell’, it worked out really well and was seen by more people than we ever, ever imagined. it turned out better than we thought that it would be and it got more attention than we imagined. we were able to launch our studio practice because of that project. we feel really lucky to have been able to do it.

a lot of people want to have their own studio and they might start straight out of school. we didn’t; we each had 10 to 12 years of experience when we began, so it felt like the right time. we both had developed a lot of knowledge, contacts and experiences

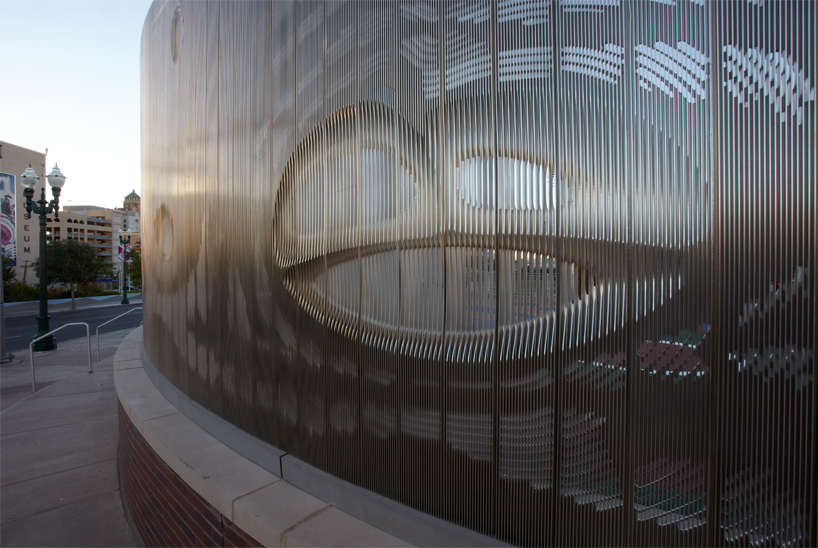

not whole fence, southwest university park, texas, 2014

image © marty snortum

continued…

GN: it is important to say that we knew what we didn’t know. a lot of people don’t know what they don’t know, whereas we always knew when and what questions to ask of more knowledgeable people. I think that this was all a result of our experience, of having worked for a while.

BB: we didn’t foresee the amount of media attention that ‘maximilian’s schell’ would generate. for its time, it used new technologies; the materials were also new for architecture. it looked good when seen in person, but it was also very photogenic. it was difficult to take a bad picture of it, so images spread across the internet – that was an unusual phenomenon at the time. internet media and spatial design were not intertwined as much as they are today; images weren’t going viral back then to the extent they do today. it was an early example of a viral sensation. we got offered a lot of opportunities because of it.

GN: we both had professional jobs at that time, so it was a huge leap of faith to quit and start our own studio.

BB: we had enough opportunities presented to us so we didn’t spend time looking for projects: they started to come to us. however, it was difficult to support us financially from the work. there was very little left to pay us.

GN: at that time, the projects’ budgets were tiny. we were ambitious and pushing the boundaries of what we knew we could do with the money we had. we put a lot of effort into the work and maybe not so much into the rest of our lives. I created a lot of havoc in our personal lives. my gas was shut off for several months.

BB: we kept our overhead low, kept our space small and affordable. we put a huge amount of effort into the studio, and it took many years to make any money. it is still difficult to sustain financially. because it doesn’t have a playbook, there is a lot of risk inherent in our work. there are blind spots that come up and cost money. clients don’t always want to pay for the research and development that goes into new work. that is where a huge amount of effort and money goes prior to giving a project clear form.

not whole fence, southwest university park, texas, 2014

image © marty snortum

DB: you have mentioned how important the research and development aspects of your work is, how do these align with your design philosophies especially your design by crafting method?

GN: the crafting and manufacturing processes fascinate us. there are machines out there that have extraordinary capabilities, but they are just tools and in the end, almost everything has to be put together by hand. we have always been really interested how existing crafts present new possibilities, especially when we apply current technology; so much potential can be pulled out of existing manufacturing methods.

BB: we first look at developing a method of making pure structure without the interference of program, use, etc. then we make a prototype to understand the potential of the production methods and how they can be applied to a space. for example, we started working with a paper process ten years ago that evolved to produce the ‘pulp pavilion’ at the coachella festival in 2015. when we began tinkering with sprayed pulp it wasn’t our intention to build a pavilion for a short-term event, but we recognized an opportunity to deploy and utilize this method once the opportunity to work with coachella presented it. we realized that it was an ideal material, process and aesthetic to present at a youth-orientated music festival in a desert. it was a perfect opportunity to explore paper’s disposability. the intense sun, heat, and wind of the desert presented an opportunity to relatively quickly cure the material. it wouldn’t have been feasible to build the project in a cool, humid climate like london.

GN: for the ‘pulp pavilion’, conceptually everything lined up. the setting, the timeframe, the climate, the process, the form, the material, the disposability; it all made a lot of sense. our richest projects come out of all these aspects being in alignment.

BB: our studio isn’t an academic materials laboratory; we aren’t developing techniques and methods and then writing about them or presenting them at conferences. the stakes are different for us. we are trying to bring programmatic, cultural and aesthetic meanings into the project, rather than isolating processes, techniques and form, and viewing it in a vitrine. we like pure research, but we want our work to be something that can be tested by everyday use while participating in the media of architecture and design. we want to be part of a bigger discussion. we like academia but we don’t want the work to be meaningful for only an audience in the ivory tower.

GN: we want to build things. the design concept is important, but building a work is just as important. making is proving the concept. realizing a project contributes to the theory.

BB: developing a process of constructing the project contributes to the concept. we ask ourselves, how does it get used, how is it perceived, how is it interpreted by the media, what happens between the speculation, the drawing board and the physical manifestation?

pulp pavilion, coachella valley music and arts festival, 2015

image © chris ball

DB: referencing the ‘pulp pavilion’ where you used this innovative paper construction, what are your personal opinions on temporary urban installations versus permanent ones?

GN: of our own work, I don’t think I have a favourite one. in the end, it depends on the specifics of each project; the specifics are what make the work challenging and fun. each project has its own problems that we must address. I think the idea and understanding of the product’s life cycle is a good way to look at this question. to develop an understanding of the life cycle of a material and its afterlife can answer a lot of the project’s brief. it can establish whether it has potential to be temporary or permanent. I don’t personally have a preference. I have techniques that I appreciate and like more than others, but I wouldn’t say that I would want to work on one life cycle of installation over another.

BB: there was a period where we were more identified with temporary stuff, but I think this came out of the opportunities that were presented to us at the time. ‘temporary’ was the type of project that clients were willing to give us – temporary installations typically involve less risk for the people who pay for them. we want to make things. it is important that our ideas are realized, and if a temporary installation is the best opportunity we have, then we are going to take it, and dive into it as much as we might for a project with a 100-year lifespan and 100 times the budget. I will say, however, that temporary projects offer something that a permanent one typically cannot – it affords us the opportunity to be more flippant, and critical. a general audience will let you challenge good taste and conventional thought for short periods of time, but if the time frame is years, then the pitchforks might come after you.

GN: we can consider materials in a different way as well. I think that temporary ones do allow us to think a bit more freely.

BB: the ‘pulp pavilion’ doesn’t set the same expectations as some other temporary installations might. it existed for a very brief moment (two weeks) and so we could communicate different ideas than we could with something designed for a longer life. we were able to craft a response to the conditions at the moment the work was made and in the immediate context. had we built a building – its context would change over its long life. a temporary project exists in a small slice of time. it can respond to its context in a singular moment. this type of project allows us to be critical in ways that we can’t with permanent things.

pulp pavilion, coachella valley music and arts festival, 2015

image © joshua white

DB: you are both working with so many different materials and different techniques, what manufacturing methods and materials have you come to best understand?

GN: none of them. I think that there is still much more to learn. if anything, whenever we start producing work using a new method we try to learn more about it. we are pretty self-critical; we usually see how a new advancement could have helped a past project. how can we apply a process again but with modifications and improvements? I don’t think that we have mastered anything. even after we tire of a material we keep interrogating it in an effort to see if we can do something new.

BB: have we mastered anything? I don’t know, but we have definitely surprised ourselves with certain materials, string, chain, and paper pulp. there aren’t a lot of people that we know working with this kind of stuff so I suppose we do understand them the best!

GN: maybe we have mastered the design of a process, methodology or a way in which we experiment and ask questions. that is something that I think we are pretty good at, but as far as a technique and a material goes, we are still learning about them all. there are always more techniques and materials out there.

BB: if something ceases to be interesting then it is usually time to retire it. I think that our work is about not being defined by individual venues, but being defined by the progression of a material investigation. each venue is a milestone where we have tried to actualize a variation and learn from it. we adapt the process again and again; we build upon it. that is our long-term project; it is where we discover secrets. we might have had individual projects, but the generation of knowledge about a process and material links them all.

GN: they are all at a very similar level of experimentation and questioning of these materials. the process of our research and development of materials is easy to switch between different projects.

air garden, los angeles international airport, 2014

image © kelly barrie

DB: outside of architecture, art and design, what other interests do you have and how are these influencing your work?

GN: ideas just come to me at odd, strange times. a lot of times, I feel that I get my best ideas when relaxing, and have actually taken a step back. for example, I am interested in fabrics and structures that are formed by air being rammed into them. I love those kinds of things. it comes out of my paragliding hobby, for which I just got my pilot license. I go flying on the weekends, and find the actual fabric structure super cool because it is literately nothing more than fabric that becomes rigid when it responds to movement and air. the fabric becomes aerodynamic when you actually fly with it. I find it fascinating and hope that there might be some kind of project to do with this someday.

BB: I am interested in industry, how things are made; however, I let other influences into my process. there is a lot of travel involved in our projects, and so, when I am on the go, I look at the history of places and try to pick up on the stories about places. I don’t know how that directly makes its way into our work, but it is something that is always on my mind during a project. I also look at a lot of art. I am thinking about how the role of the designer is changing – is there a place for design and art in the same conversation? how can one comment and challenge the division? I learn from people who transgress disciplinary boundaries.

air garden, los angeles international airport, 2014

image © kelly barrie

DB: as we are at your studio here in los angeles, how would you sum up the current design and architecture scene in the city?

GN: though our studio is in los angeles, we work all over the united states and the world. out of the dozen projects that we are working on, only one is in LA.

BB: we do like working here. we like to contribute to the discussion that is taking place in los angeles. this city is a place where design, art and architecture conversations are happening, so to show something here, is to present work to an engaged and knowledgeable audience. we have made some of our best projects for smaller cities, but we don’t get the same level of critical feedback. when we present work in LA, we might get a harsh reception, but it is usually stimulating and helpful.

it is hard to say what defines the design scene in los angeles at the moment. the things that are defining it today are quite different than what was in the past. one thing is for sure; the reach of its design is global whereas in the 50s, 60s and 70s, there was awareness of LA, but not like what it is today. when I first came here 25 years ago, it felt like there was a movement happening, but the rest of the design world weren’t paying much attention to it. it seemed a bit unhinged from history. the architects and designers, who came here in the mid 20th century, were unorthodox modernists like rudolph schindler, richard neutra, and gregory ain. they were doing things that might not have happened on the east coast. you can now drive through los angeles, peal back its commercial crust, and see an incredible melange – different design outlooks side by side. this collage aspect is fairly unique to LA. maybe because the city is relatively young and when it exploded in population in the 20th century, it expanded sideways. it grew immensely from the mid 20th century onward.

GN: the one thing that is terrible, which is going on here, is the developer architecture. that is one of the least positive things happening in the city because it is creating the most mundane architecture you could possibly imagine. it is caused by attitudes based on economics and nothing else, but I think that there has to be something else, some sort of ambition and bigger idea that you want to push. I am really disgusted by some of the seven or eight storey, mixed-use buildings constructed recently. they aren’t contributing to the urban structure of the place. the only contribution that these horrible things bring is more fast food restaurants and convenience.

BB: this is one of my theories about it; LA expanded horizontally with the advancements of the car and highway system, and when combined with cheap land, there was a frantic pace to building; it was a gold rush. people were building anything they pleased everywhere. this was happening when people were rethinking traditions in architecture so the buildings were cheap, fast and without tradition. there has always been a kind of unsophisticated architectural culture here. the developers are only sophisticated at the achieving their bottom line. for artists and designers the fast, cheap world can be freeing. they are not constrained by or judged against a backdrop of history. consider the innovative architects here who were building fast and inexpensively, but were really thinking about their work, they were responding to a very different set of conditions – speed of development, low cost and climate. that really set los angeles apart from other parts of the country. it contributed to a unique culture here but it is not the only thing that defines the city for me. the culture of architecture, art and design here is so big; there are many different scenes.

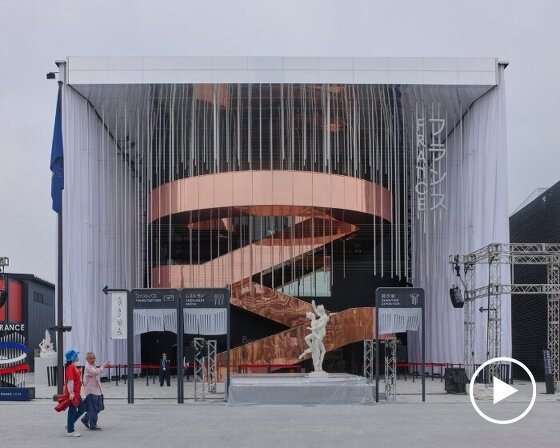

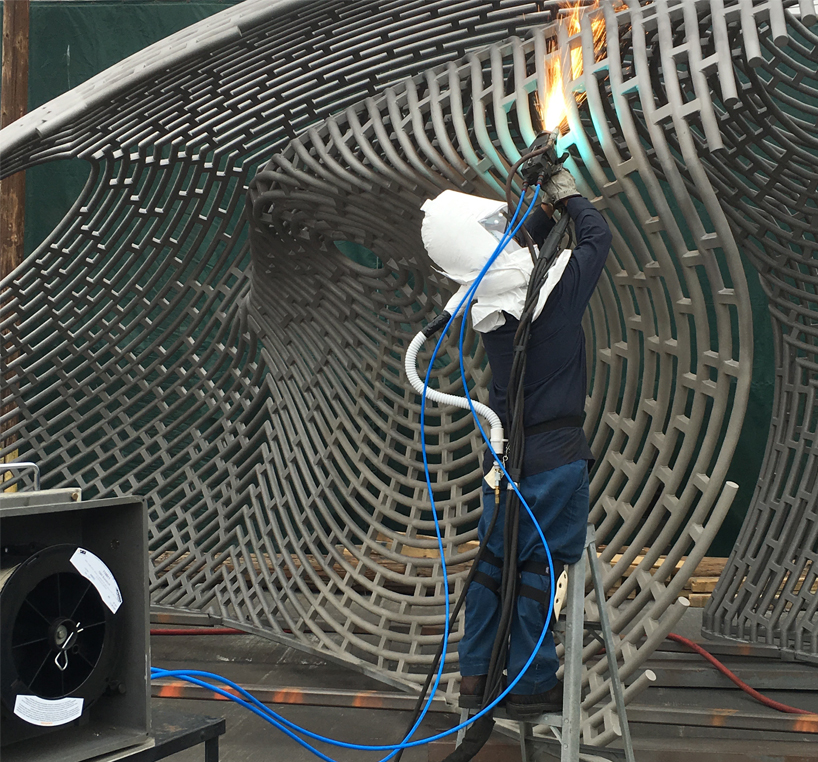

construction of the healing pavilion

image © ball-nogues studio

DB: can you tell us about some of your current projects that our readers should be excited about seeing?

BB: we are currently working on a project called the ‘healing pavilion’, which should be finished soon. it explores the challenges of bending and rolling tube steel to form a design in the shape of a shell. the result features pretty unique three-dimensional curvature of the steel, where each piece is at a fixed distance to its neighbor.

GN: its commissioned for a hospital in LA, as part of their large garden renovation. the irregularity of the tubes create a layer of transparency that provides a semi-sheltered and a very meaningful place for patients and guests to relax. it could also work as a shading device, but mainly it is an experience that symbolizes hope.

BB: it aims to take their’s and their families’ minds away from illness.

image © ball-nogues studio

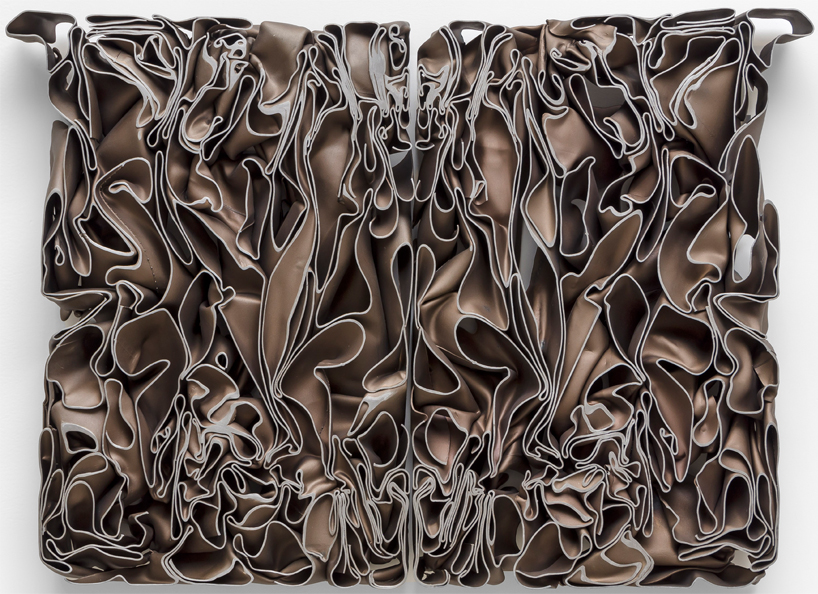

GN: we are also using steel to work on one of our other projects, ‘second hand geology’, which should be finished shortly as well. it looks at the differences between man made things and those made by the forces of the earth’s geology. its a pretty cool idea and required us to compact raw stainless steel tubes and sheets into dense blocks. you can see the test models around the studio, the crumpled metal sheets are unique and fascinating.

BB: interestingly, we produced these forms using analog equipment, even though they are very suggestive of digital design.

GN: something that is almost inherent nowadays.

BB: the blocks will be assembled to form a tall stack, like an obelisk, at the center of black hall, the college of education at central washington university.

‘second hand geology’ render

crushed metal panels for the ‘second hand geology’

image © edward cella