is art produced only by artists? or is it something ‘average’ people have routinely created throughout humanity’s existence?

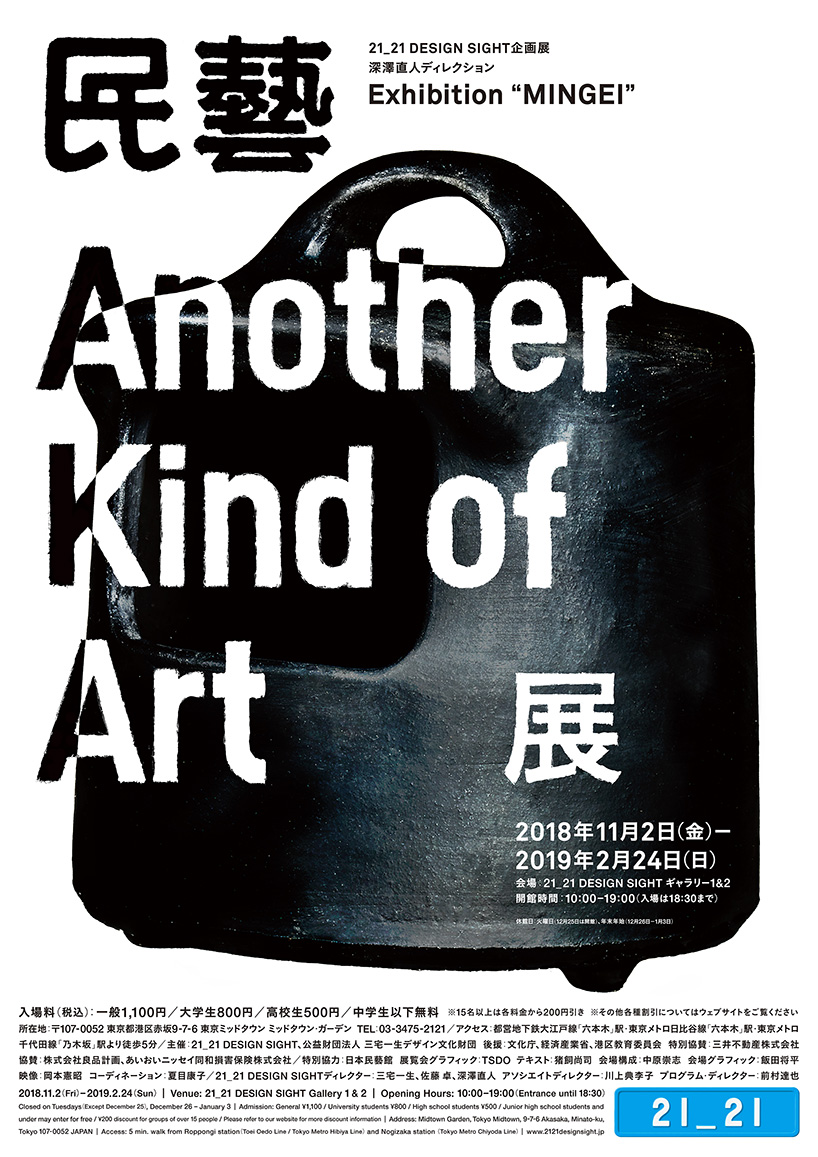

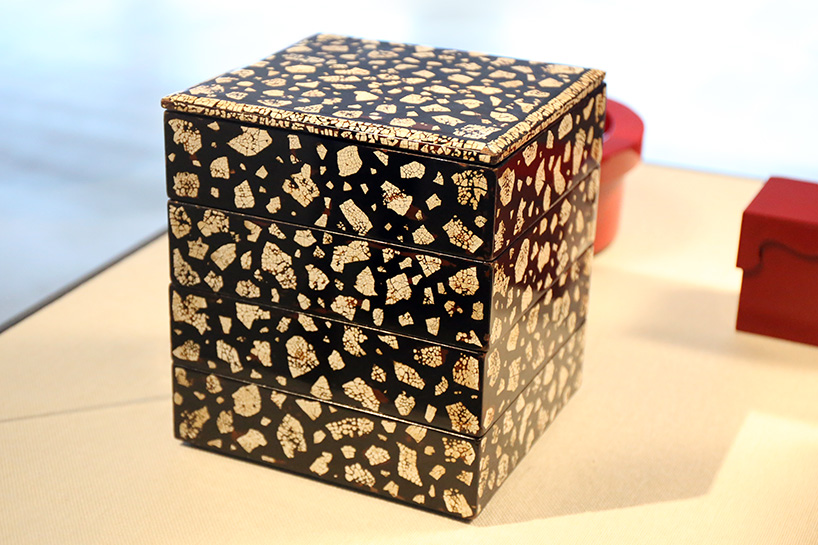

21_21 DESIGN SIGHT in tokyo currently shows ‘mingei- another kind of art’ directed by product designer naoto fukasawa. the exhibition features 146 traditional and contemporary ‘mingei’ items from the japan folk crafts museum’s collection (fukasawa is the director of the institution). they are displayed alongside straightforward statements by him regarding their appeals. in addition, the exhibition introduces the faces of ‘mingei’ in today’s society through a film capturing the lives and work of the creators of ‘mingei’ and the people who promote it. naoto fukasawa’s personal collection, and photographs revealing new forms of ‘mingei’ are also on display. the ‘mingei’ exhibition at the tokyo 21_21 DESIGN SIGHT runs until february 24, 2019.

a view into the mingei exhibition, image by masaya yoshimura

main image: naoto fukasawa selects exhibits in a film by noriaki okamoto, courtesy 21_21 DESIGN SIGHT

designboom has a strong interest in ‘the essential nature of beauty’ and in documenting the factors that combine to render an object beautiful. for the exhibition at 21_21 DESIGN SIGHT opened, we were able to interview with naoto fukasawa and ask him a set of questions to reach an understanding of that ‘mingei’ beauty — how, in other words, to appreciate it.

designboom (DB): personally, why is it important for you to communicate traditional craftsmanship to the world?

naoto fukasawa (NF): after working in the design field for a long time, when I see an object, I can see more or less the process of the idea and how the shape has been created, but I can not see it from these objects here. there is a selfless beauty that is beyond our imagination. they have not been created by great artists, or takumi (meaning japanese traditional craft master), but ordinary people. their pure, casual, free power of the imagination touches my heart and I respect them.

a view into the exhibition

image by masaya yoshimura, courtesy 21_21 DESIGN SIGHT

there are mainly two types of crafts: signed items by the artist-craftsman and unsigned work made by a folkcraft community or by individual artisans. the artist-craftsman fosters individualism by having an individualist approach to his work. his products are few and expensive, they are becoming luxury items. made for collectors, often the work is more ‘decorative’ than useful.

and folkcrafts instead, move from fine-arts toward art of the people. traditionally, ‘mingei’ art is anonymous, and individual artists should not expect recognition. however, modern attitudes have changed on this principle. the idea is that they should be appreciated as objects of the masses.

DB: do you think society benefits from the artist-craftsman and why?

NF: after being inspired by mingei, I would like to place this ‘indescribable fascination’ on stage for people to see. in other words: only good design is not enough. I want those who work creatively to see this exhibition and to have the same surprise in the discovery of mingei and to feel jealous as a cause of it.

modern photographs of mingei ‘lidded chrysanthemum-shaped food container, made of mold-blown glass’

image courtesy mariko ohya

the defining characteristics of ‘mingei’, which draws on climate and custom, are handed down from generation to generation, developing originality in material, color, process, application, shape and so on, and evolved into innovative, impulsive, imaginative and original work not restrained by any one form or genre. in today’s world, unique characteristics of individual regions are diluting, and affection towards items is dwindling. that is precisely why the innocent aesthetics and spirit of ‘mingei’ has such a strong impact on not only users, but also all people involved in making things, and provide them with triggers to create new energy for a coming era.

tea storage jar with trailed white graze / tsutsumi (miyagi) / latter half of the 20th century (owned by the japan folk crafts museum)

image © designboom

DB: how does the exhibition highlight the defining characteristics of mingei?

NF: what I feel for everything is a vague prettiness. I think it comes from the axis of soetsu yanagi’s atheistic sense. and it is a thing(object) with an indescribable fascination which you want to put it at hand and to love it.

DB: the works are displayed alongside written statements — how do these thoughts intend to enhance visitors understanding of the objects? and what are the reactions you hope visitors take away from the exhibition?

NF: in the exhibition, I have omitted the detail description about the time, the use, the region, etc… instead on behalf of them, I have added a short text which express ‘a mutter in my mind’. according to the words from yanagi, I hope that visitors see the works with their impression. rather than the information – this has been made when or where, how, or something… – instead I hope visitors share the impression or compare their feeling with my words.

hot pad / shimane / showa period, 1930’s (owned by the japan folk crafts museum)

image © designboom

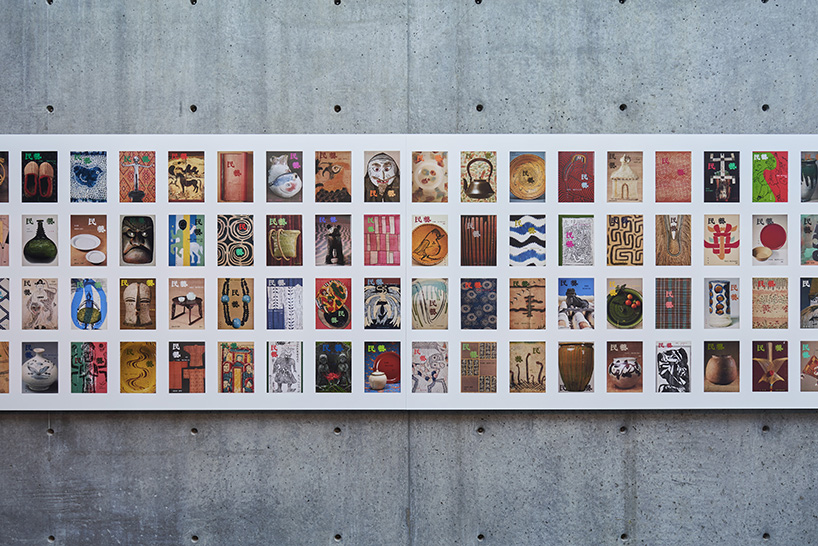

furthermore, this exhibition gives a new glance at the history of ‘mingei’ by presenting soetsu yanagi’s ‘nihon mingeikan annai’ (introduction to the japan folk crafts museum) and ‘verses from the heart’ — expressions straight from the heart conveyed in short phrases; the in-house magazine, ‘mingei’, for which sori yanagi oversaw the cover layout, ‘the mingei movement film archive’ which captures the handicrafts during the early phases of the ‘mingei’ movement, and so forth.

a view into the exhibition

image © designboom

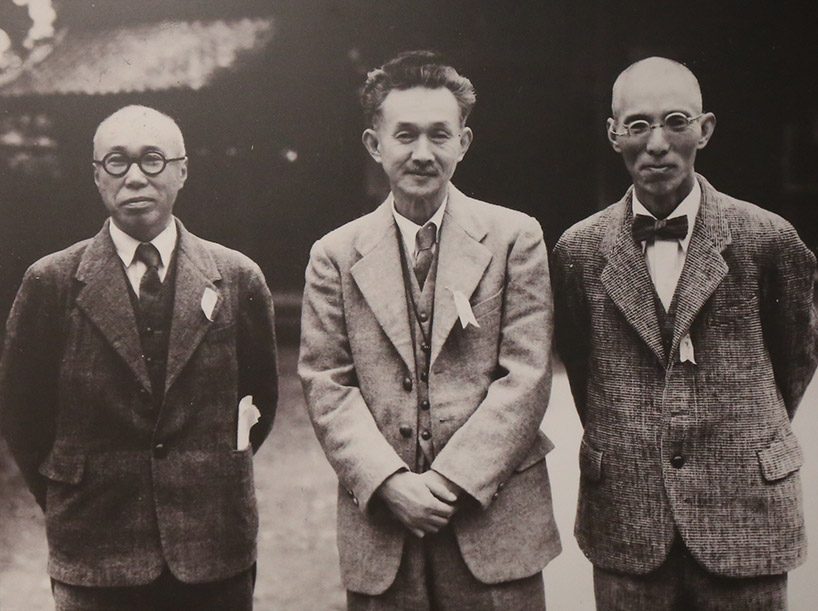

in 1925, together with kanjiro kawai (1890-1966) and shōji hamada (1894-1978), soetsu yanagi (1889 – 1961) first named handicrafts made by anonymous craftspeople ‘mingei’, as he recognized the beauty in these everyday items used by common people. the name ‘mingei’ is a combination of ‘min’ (民), meaning the common people, and ‘gei’ (芸 or 藝), meaning art, and is also an abbreviation for ‘minshuteki kōgei’ (民衆的工芸), which literally translates to popular industrial arts. by stressing the importance of mingei as a movement that would evolve in parallel to wider society, at a time of japanese military imperialism and nationalism, soetsu yanagi defended the cultural originality of the peoples which japan was seeking to assimilate: the people of korea, okinawa and taiwan, and the ainu minority in northern japan. this collective realisation, which did not reject modernism and which benefited from the arrival in japan of bruno taut, charlotte perriand and isamu noguchi, expressed itself in certain design aspects from the post-war period onwards, when the action of sori yanagi, son of soetsu, was decisive.

a view into the exhibition

image by masaya yoshimura, courtesy 21_21 DESIGN SIGHT

soetsu yanagi devoted himself to developing and spreading mingei philosophy throughout the country, culminating with the 1936 opening of the japan folk crafts museum. yanagi himself designed the main hall of the museum, and in 1999 the building became a registered tangible cultural property of japan, and still houses exhibits to this day.

a view into the exhibition

image © designboom

the principles of mingei

there are a few principles and characteristics that define what types of folk arts and crafts ‘mingei’ deals with, mostly proposed by soetsu yanagi (excerpt from the book ‘the unknown crafsman’):

– mingei art should be produced in large quantities by hand.

(editor’s note: the hand-made nature, and the fact that it is produced in large quantities is related to the utilitarian aspect of ‘mingei’.)

– mingei art should be inexpensive, simple, and practical in design. unlike ornate luxury items, the simplicity and inexpensiveness is what should give this art its charm.

(ed. in today’s world though, the high costs of artisan manufacturing makes this principle a less adeguate one.)

– mingei art should be not only functional, but also actually used by the masses.

(ed. the beauty of these objects comes from their actual usage, not simply being admired. their use also gives them their cultural and regional authenticity.)

– mingei art should represent the region in which it was produced.

(ed. this reflects japanese culture’s appreciation for regional variation, and indeed mingei art often has distinguishing characteristics unique to specific regions of japan.)

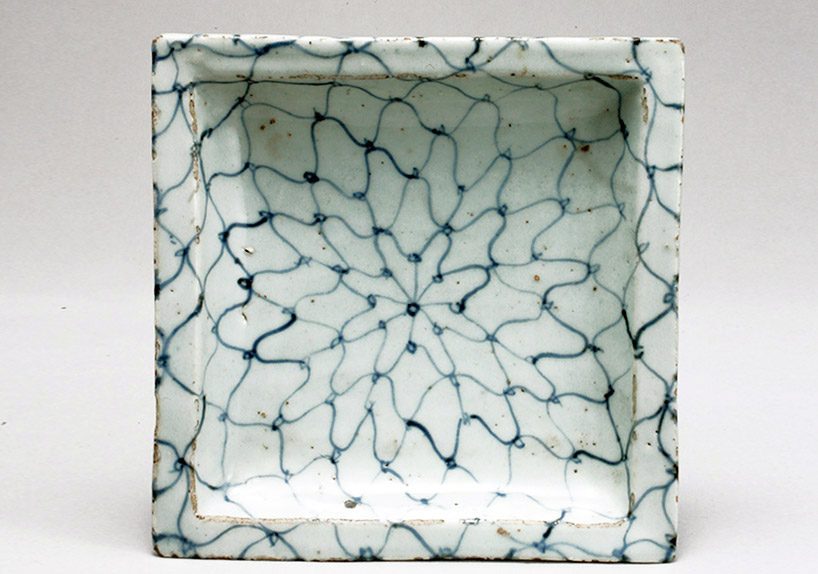

plate with reticulate patterns, jingdezhen (china), ming dynasty, 17th century

image courtesy the japan folk crafts museum

enthralled by an attitude of honest creation

there is something indescribably charming about the objects created by the selfless hands of someone who is neither an artist, nor a craftsperson. ’it took me four years to paint like raphael, but a lifetime to paint like a child.’ are picasso’s famous words. this sentiment was in common with soetsu yanagi and alludes to the pureness that a devoted mind instills in a creation. samiro yunoki, a stencil dyeing artist who is still passionately active at the age of 96, took me by surprise when he said ‘I am not seeking a title of stencil-dyer or a category of mingei. I simply seek another kind of art.’ this instantly made me think that the ‘mingei’ coined by yanagi is in fact expressing the way of life of the people who create it. these honest creators want anything but to be slotted into a category. if they look likely to be, they will unconsciously want to break free. they possess an aloof attitude of not wanting to be restrained by form or method. mingei entails a freedom of not demanding a set finished look. we love, respect, and are moved by mingei. we don’t need information about who, when or how it was made. it’s simply about looking at a creation, being enthralled by its charm and thinking ‘wow. this is amazing.’ naoto fukasawa from the director’s message for ‘mingei – another art of kind’.

from left to right: pottery artist shoji hamada, soetsu yanagi, pottery artist kanjiro kawai – major figures of the mingei folkart

image courtesy the japan folk crafts museum

in the book ‘the unknown crafsman’, soetsu yanagi embraces the buddhist idea of beauty:

‘the state of liberation from all duality, a state where there is nothing to restrict or be restricted. beauty, then, ought to be understood as the beauty of liberation or freedom from impediment. (…) true freedom must mean liberation from both one’s self and others. (…) everything that is beautiful is, in one sense or another, a manifestation of this sort of freedom.’ he then continues, ‘all art movements tend to the pursuit of novelty, but the true essence of beauty can exist only where the distinction between the old and the new has been eliminated.’

samiro yunoki “stencil-dyed doorway curtain with a design of paired faced mouth open and closed” (owned by the japan folk crafts museum)

image © designboom

the book ‘the unknown crafsman’, soetsu yanagi also gives three pieces of advice to achieve ‘a direct eye for beauty’:

‘first, put aside the desire to judge immediately; acquire the habit of just looking. second, do not treat the object as an object for the intellect. third, just be ready to receive, passively, without interposing yourself. if you can void your mind of all intellectualization, like a clear mirror that simply reflects, all the better.

finally, the exhibition introduces the items created by present-day people who carry on the ‘mingei’ tradition in various regions throughout japan.

image © designboom

in the exhibition , the covers of themagazie ‘mingei’ which directed by sori yanagi, an industrial designer who also served as director of the japan folk crafts museum are on display.

the exhibition unravels the story of ‘another kind of art = mingei’, which will be the basis of design inspiration into the future

image © designboom

items created by present-day people who carry on the ‘mingei’ tradition in various regions throughout japan

image © designboom

happening now! thomas haarmann expands the curatio space at maison&objet 2026, presenting a unique showcase of collectible design.