sam lewitt isn’t an artist whose opus can be easily defined. rather than being assigned to any specific creative medium or means, lewitt openly investigates information and matter, unfastening closed systems and institutional structures in the process. ‘I like this picture of neat tidy, categories, but that’s not how I see it,’ the new york-based artist tells designboom about his relationship to defined artistic terminology. ‘I think that artworks, like scientific phenomena or technical phenomena, are made up of complex social substance. they’re more like prisms that can be turned and seen from different perspectives depending on the institutional context which sediments the discursive context.’

image © designboom

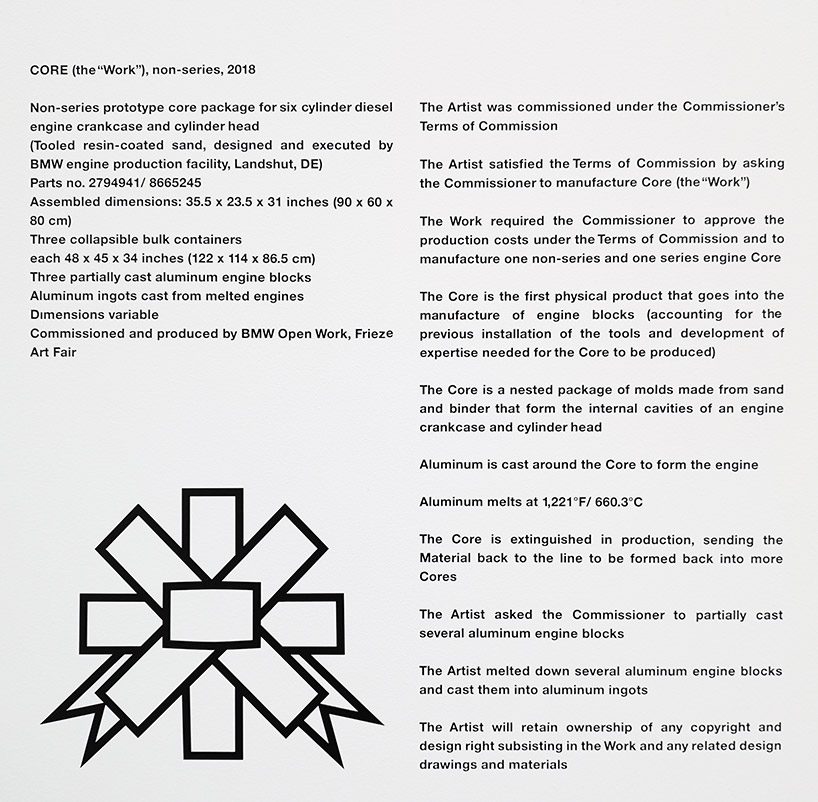

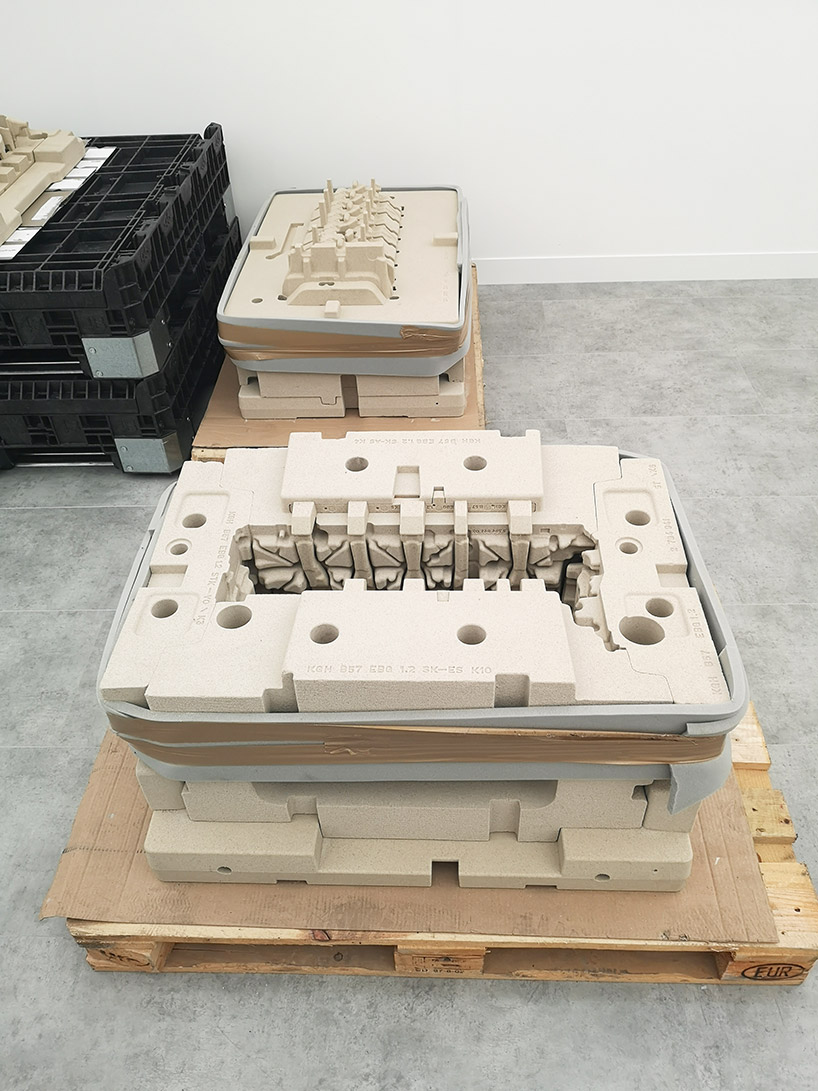

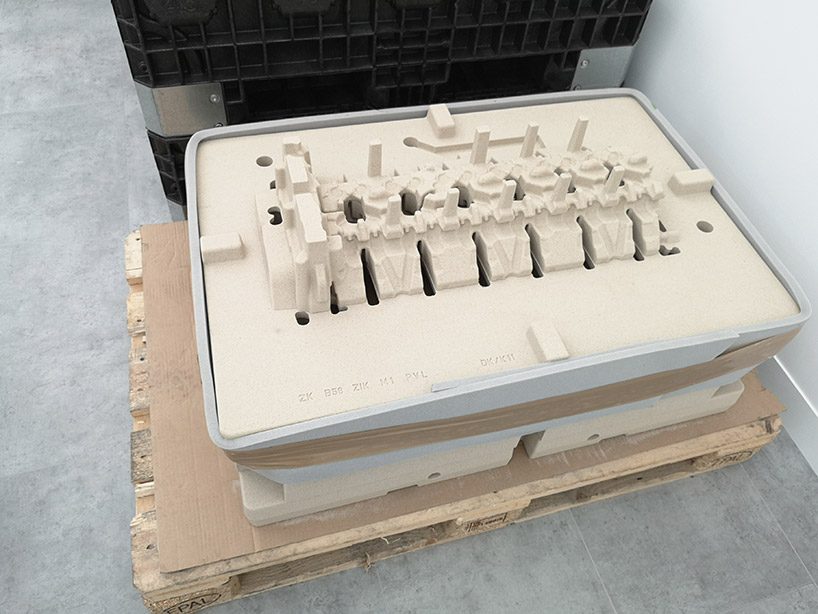

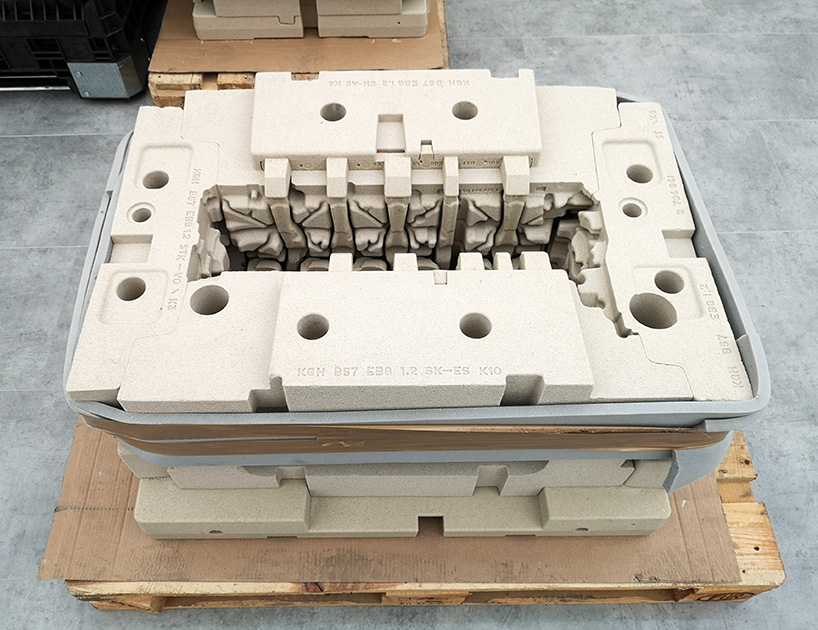

in this vein, lewitt exhibits an ambitious new installation as part of the major artistic initiative, BMW open work, curated by attilia fattori franchini and presented at frieze london. largely informed by the artist’s dialogue with BMW engine specialists, CORE (the ‘work’) reimagines the manufacturing cycle as an engine in itself, using physical ‘archaic’ materials — like sand and aluminum. ‘I’m interested in the components that are literally at the core of the technological developments that facilitate driving experiences,’ lewitt explains.

image © designboom

while conceptually and physically, the installation uncovers the production cycle of a BMW engine, ‘CORE (the ‘work’) also exposes the unique process of being a commissioned artist, and in turn engages with the structure of the commissioning system itself. in fact, lewitt actually recommissioned BMW’s engine manufacturing plant to create physical pieces of installation. excerpts from lewitt’s contract with BMW are imprinted on the walls, a document which he sees as ‘more of the medium of the work, rather than the physical materials they are produced out of.’

at frieze, designboom spoke with lewitt about his unconventional response to the commission, artistic abstraction, and the overall evolution of his thinking and work.

the work engages the very structure of the commissioning system by congealing different flows: of matter, of the costs of a production line, of cultural investment and its relations of symbolic and material exchange

image © designboom

designboom (DB): tell us about the installation, and how you first approached the commission for BMW open work.

sam lewitt (SL): the piece is called CORE (the ‘work’). the graphic form of the title is actually quite important for me because in some sense, it’s a work about a request for work, or the type of requests, and the types of demands and obligations — both informal and contractual — that are part of a commission. my interest in doing this commission had mostly to do with producing an unusual circuit within the commissioning system itself, where I was commissioned by BMW to produce a work. at that point, the work was indeterminate.

curator attilia fattori franchini and thomas girst, global head BMW group cultural engagement, on lewitt’s work

DB: how did you choose to respond to the brief?

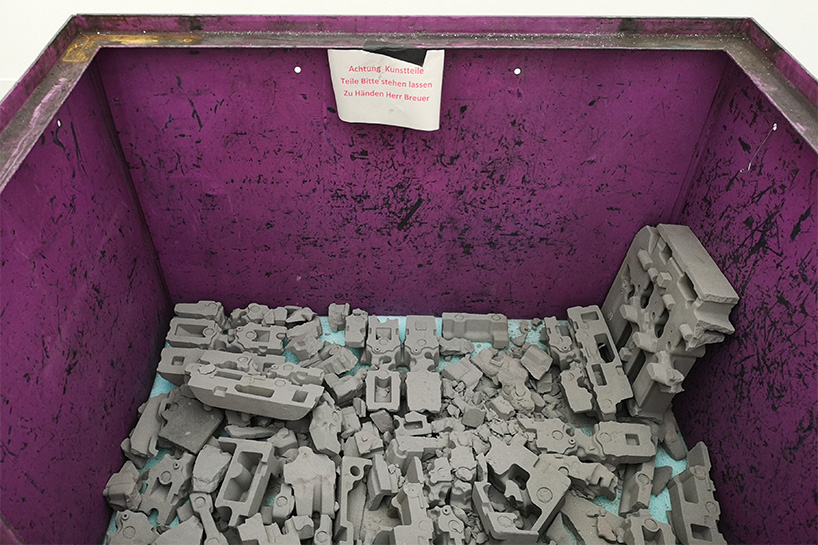

SL: my response was to then commission the commissioner to produce the work for me, according to the budgetary restrictions of their initial request. what I ended up with, happily, was two full ‘sand cores’. they’re essentially molds made out of sand and binder of the entire engine block. it’s the first physical product that comes off the production line in the manufacturing of an engine. this kind of condensation and packaging of the work — both the artwork and the labor that has to be purchased — became the primary focus what I was interesting in doing and achieving.

image © designboom

DB: how do you define the original state of the thing you are investigating and in turn abstracting?

SL: the ‘real abstraction’ in this case would be not the simple exchange of money, but the way that the exchange of money is already packaged with a set of rights and obligations that determine the meaning and the form of the exchange. the contract for the commission — of which I have excerpted and abstracted as texts on the wall — became almost the medium of the work, rather than the physical materials they are produced out of. in other words, the social relations that have to be negotiated and the contract is the medium of the work. that issues into a set of requests — requests of me and, in turn, requests that I made onto the commissioning institution.

image © designboom

DB: the work is quite analog — can you elaborate on your relationship towards the digital and analog?

SL: I think there’s a fetishism for technological doodads and gadgets, and sometimes really world-altering technological developments, but when I think of this particular context and I think of cars, I mostly think of technological ad-ons that change your experience of driving — and I’m not overly interested in that. I’m interested in the archaic components that are literally at the core and support those technological developments that facilitate those driving experiences. sand, aluminum, melted metal is this archaism that persists. I don’t know if it’s even a question of analog or digital. I hope that it’s a more complicated picture of the mostly ideologically bankrupt claims of the defenders of digital culture.

image © designboom

DB: what do you hope viewers take away from the installation?

SL: I’d like people to see the work as a fragment of reality that is part of the ubiquitous experience of that reality, but is still somewhat alien and estranging. that’s quite interesting for me.

image © designboom

DB: what is the intended result?

SL: I think critical efficacy comes with trying to locate insoluble contradictions and then trying to clarify, not resolve, the form of the contradiction. this is what I want the work to do — to throw into relief the strange contradictory relationship that crystalizes around things like, say, intellectual property rights. my contract says, once I call it ‘the work’ I have rights over it as my artwork, but yet it’s the product that comes from BMW, the commissioner, for which they want to claim rights. that produces a kind of contraction, which is encoded into the DNA of the work. I hope it’s clarified by the work itself, that this is a sort of insoluble relationship.

image © designboom

image © designboom

DB: how do you view the evolution of your work?

SL: the work I’ve done tends to have one problem that it’s dealing with, and that’s what we’ve been talking about now. in a very abstract way, that problem has something to do with attempting to put myself and the viewer in a situation where you have to coordinate and mediate a number of discursive problems and a number or material, physical almost dumb facts. so to place myself, and also to place viewers, in that kind of gap is the consistent thread. I think since maybe the 2012 whitney biennial, these are the concerns I’ve had. I think I’ve consciously tried to keep it quite consistent, because I feel like I haven’t exhausted my own questions about it. once I’ve exhausted those questions, I’ll leave it alone.

image © designboom

DB: was your work for the 2017 venice art biennale drawn from a similar line of thought?

SL: for ‘stranded assets’, I drew from the giuseppe volpi power plant that was built in 1922 — the same year mussolini was elected. volpi was the president of the biennale in the 30s, and he changed the energy system in veneto. he took the energy turbines out of the arsenale and built a giant power plant in margehera — the first one in margehera. the building was recently decommissioned and I was curious about this history, so I went there. I found these lamps that were designed for the original building, so I got a loan of the lamps and they lit my space in the arsenale where the turbines used to be housed. then I built reproductions of the lamps out of fuel ash, the ash that’s scrubbed out of the smoke stacks.

note: see images of ‘stranded assets’ at gallery buchholz, shown at frieze art fair 2018 in the gallery below

image © designboom

DB: what are the creative strategies you adopt when working?

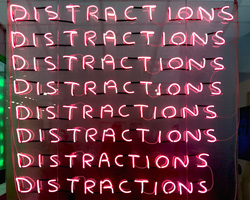

SL: sometimes strategies are consciously implemented, and other times they are imposed. boredom and distraction are good strategic allies sometimes, sometimes they can be bad. generally, I feel the work is ready to be made a matter of public document when I can describe it very precisely, but feel like that description doesn’t issue immediately into a resolution or an imperative. it’s that relationship between description as a means, and the sort of material facts struggling against my own descriptive resources. that’s something I have to go through in order to produce a work.

sam lewitt

image © designboom

BMW open work 2018

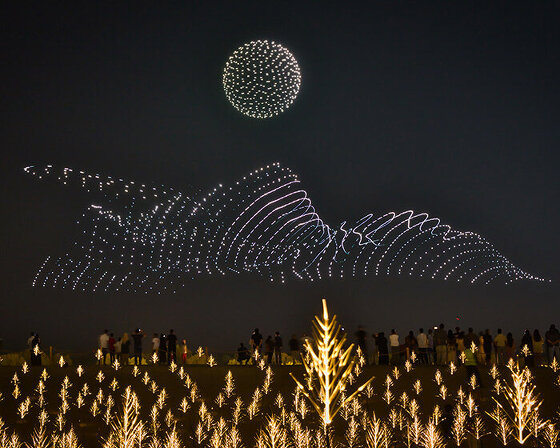

BMW group culture and frieze continue their long-term partnership with the major artistic initiative, BMW open work by frieze. curated by attilia fattori franchini, the initiative brings together art, design and technology in pioneering multi-platform formats. drawing on dialogue with BMW designers, engineers and technological experts, artists consider current and future technologies as tools for innovation and artistic experimentation, creating artworks with the potential to unfold across a range of media and exhibiting platforms.

happening now! thomas haarmann expands the curatio space at maison&objet 2026, presenting a unique showcase of collectible design.