born and raised in strasbourg, alsace, france, tomi ungerer is an award winning illustrator and a trilingual author. his work is renowned for pushing boundaries and challenging social conventions, taking issues and relating them throughout his beloved children’s literature and his more controversial adult creations. tomi is more recognized for his children’s books, which has resulted in him receiving distinguishable awards such as the 1998 hans christian andersen prize for children’s literature. however, his sharp satire work is still exhibited and celebrated across the globe more than ever. within his career, he has stretched his creativity across architectural design, invention, advertising and sculpture, leading him to work in new york, canada, ireland and also strasbourg.

tomi ungerer’s ‘a treasury of 8 books‘ published by phaidon, marks the very first time some of his most popular children’s literature will appear in the UK market. the momentous collection features a mixture of his most successful tales, including ‘the three robbers’, ‘moon man’, and ‘otto’, and a few of his acclaimed recent works like ‘fog islands and the lost gems’, ‘zeralda’s orge’, ‘flix’, ‘the hat’ and ‘emile’. coinciding with the launch of his new compilation collection, designboom met with tomi in london, UK, to discuss the many notorious decades of his work, the social issues that he tries to address throughout them, and how current affairs, such as the US election, are influencing his writing, illustrating and sculpturing today.

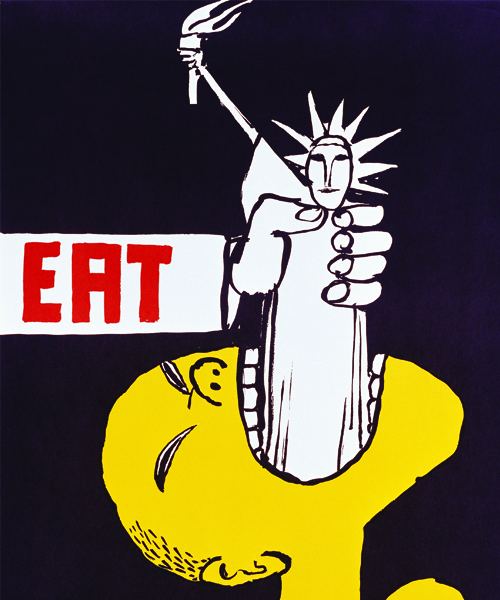

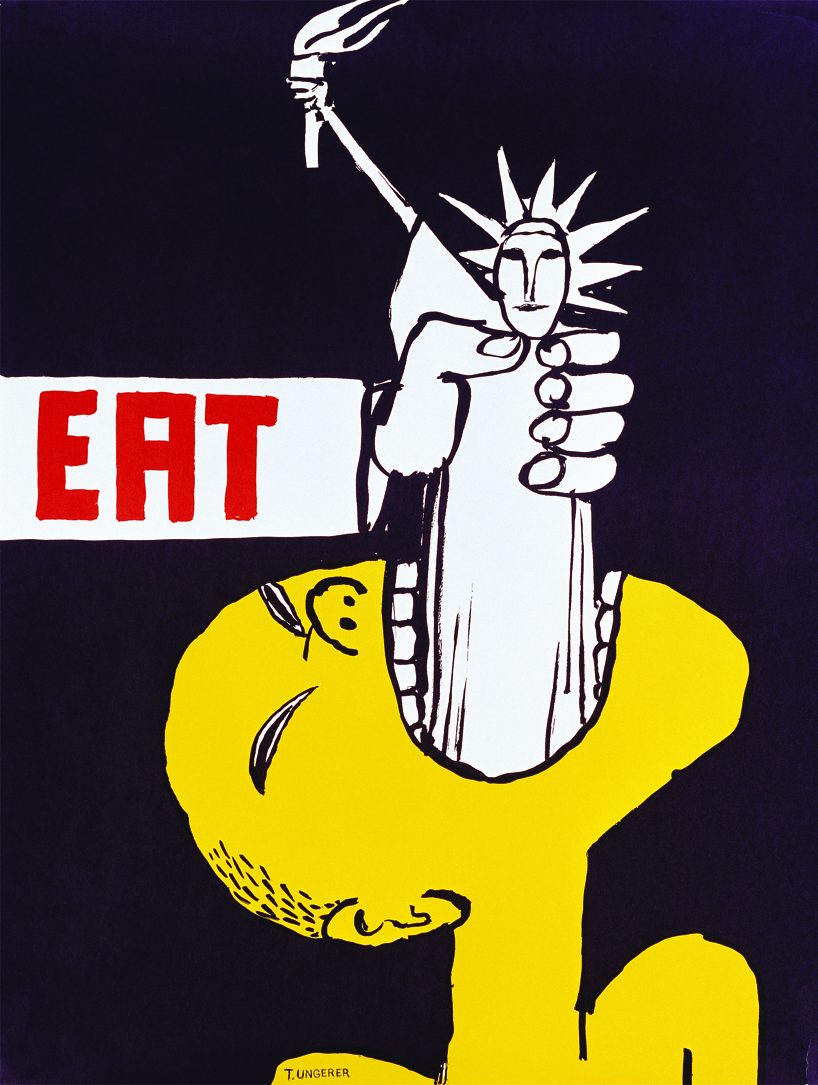

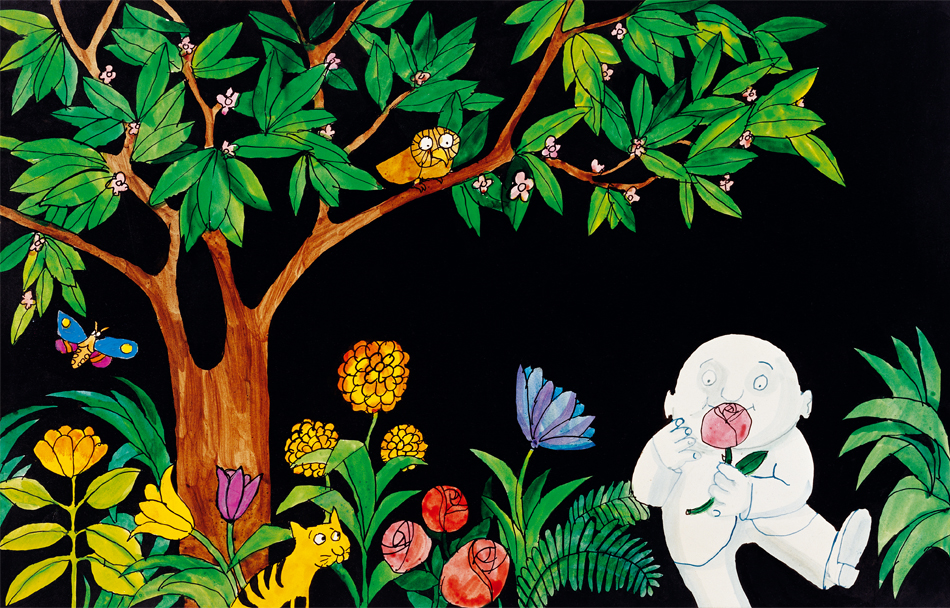

‘eat’, 1967

image © tomi ungerer

designboom (DB) apart from writing and illustrating children’s literature, a craft highlighted with the publishing of ‘a treasury of 8 books‘ by phaidon, can you talk about some of the other ventures of your work?

tomi ungerer (TU): as you may know, I have a museum in strausburg, which has all my files and old sketches, or you could go to the library of philadelphia. I am a bit of a jack-of-all-trades. it is hard to pin me down. I do architecture; I have done a kindergarden in germany, which is in the shape of a cat and the children can slide down its tail to the second floor. I am a freeman, I find lots of things interesting, and have always done what I have felt like doing. I have done an average of three or four books a year. a lot of them are satire. now I have several books coming out this year. I work every month in france, and in germany, I have a whole page in the philosophy magazine which will release their first collection soon.

DB: with producing around three to four books a year, how are you able to come up with new ideas for books and illustrations?

TU: I have kind of trained myself in a way to come up with ideas. I was never cluttered with education, high school or university degrees or anything like that. I could always study anything I wanted. all I needed was self-discipline which I am very good at. I am basically very curious. I have always said that curiosity should be triggered. once you are curious, you collect knowledge. the moment that you start to compare this knowledge, you start to develop your imagination. this is completely lacking nowadays. we are completely controlled by systems and I am basically against this because I have no computer or anything like that. I think it is an infringement on my freedom.

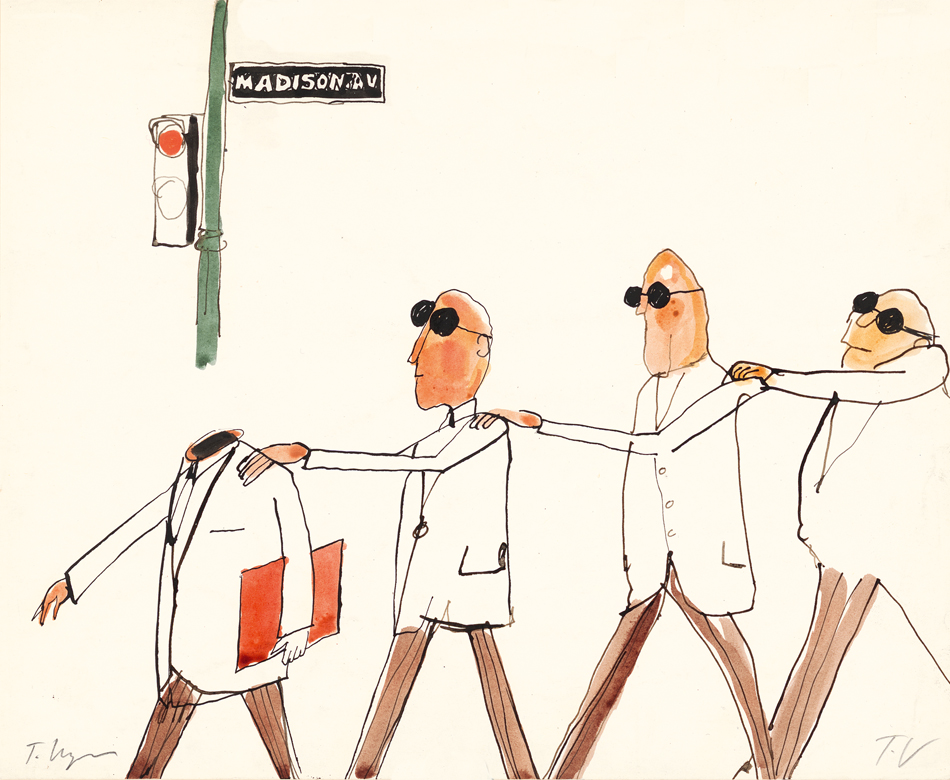

‘dr. strangelove’, 1964

image © tomi ungerer

DB: talking about your ideas of freedom, is that why you express your ideas over so many different mediums, from books to magazines to newspapers?

TU: I would be bored otherwise. it nearly gives me an inferiority complex when I see other artists who have one style and just build it up. I am a jack-of-all-trades, I go in all directions, I am interested in this and that. on one day for example, I can start working with sculptures, then the telephone rings and it gives me another idea for a story so I have to write it down. then I go back to another project afterwards. I am completely disconnected from a very good network.

DB: that is very uncommon nowadays because everyone wants to stay connected and in networks.

TU: well, I think it has always been uncommon really. I gear myself to have ideas and I am completely tyrannized by the fact that I have ideas all the time. of course, I always have my notebook in case there are other short stories for me to write down, or another thought to develop, or another sculpture to create. I do a lot sculptures these days. I just had a show in the biggest german museum in essen, and before that, it was in the museum of modern art in zurich. right now, I just had a show in berlin as well. these are all collages and all satire. some of it is very hard because all my life, I have been fighting for causes and it shows in all my work. I have always taken up issues in the hope that they create more of an understanding.

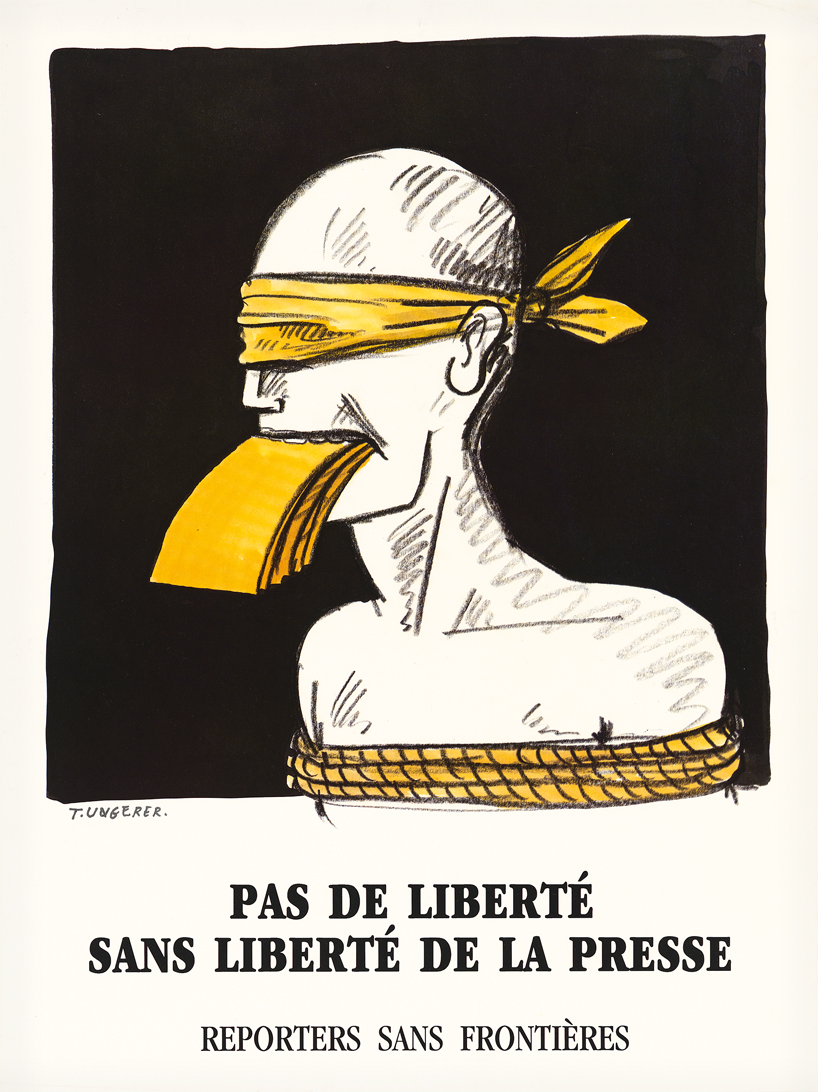

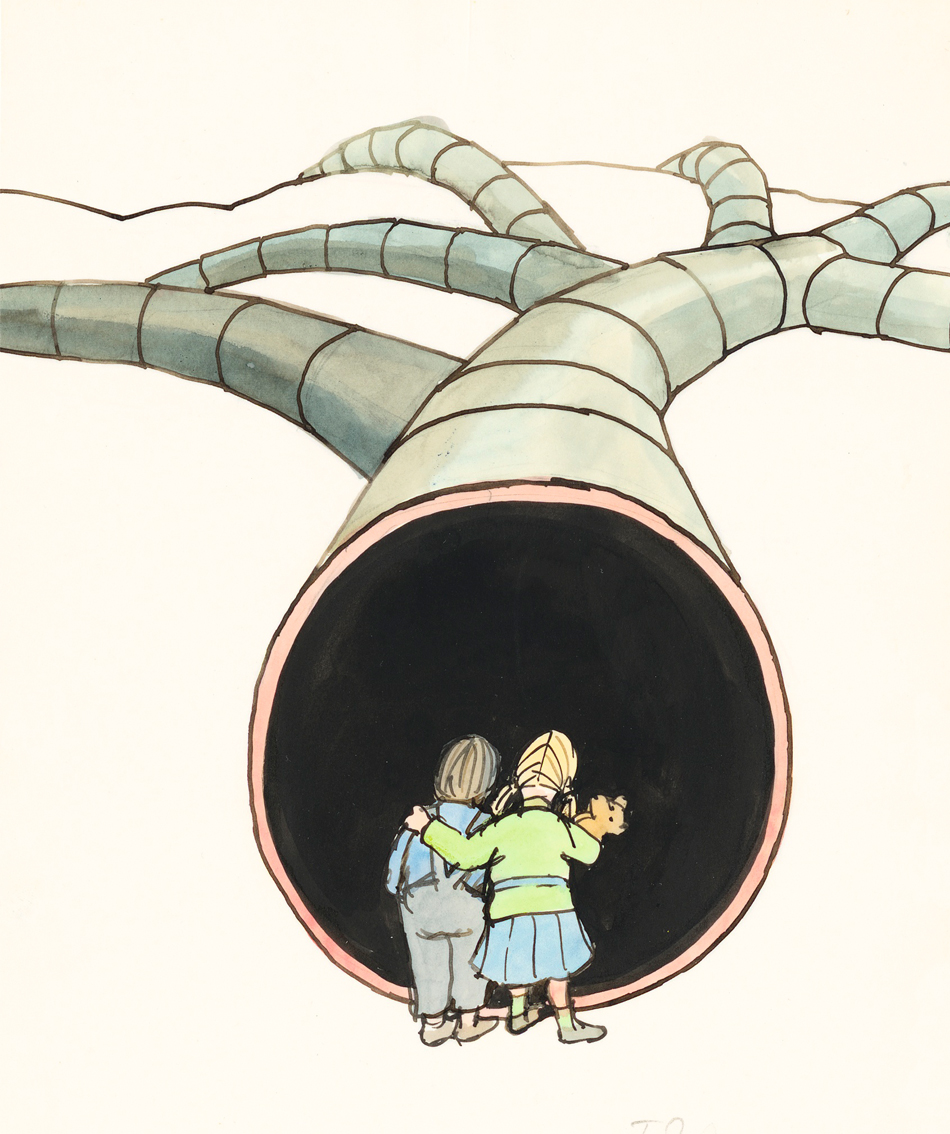

‘no freedom without the freedom of the press’, 1962

image © tomi ungerer

DB: what spurred you to first move out to the US in the 1950s?

TU: jazz, I was a big jazz fan. I thought that I would be able to see some jazz, but in america at that time, it was still segregated. jazz was part of race music early on, but luckily, this changed over time. I knew a lot of american fulbright students and I had a great admiration with saul steinberg. I went to america with $60USD in my pocket and it was the land of opportunities. I was in new york which is a completely different part of the US. I would say that 60-70% of the people that I met there, were jewish of emigrant origin. I loved new york and still love the city. for me, america is the land of essence of savages and specialists.

DB: seeing the work of saul steinberg and also andre francois, was this what inspired you to get into illustrating originally?

TU: I got into illustrating and then writing because I had the talent. I did a book about my father, which is not published in english of course. my father had every talent around, he died when I was three and a half years old, but I have always had the feeling that he gave me all his talents. since the french came back after the nazis, they made life full of authorization and it was very difficult. I was encouraged to study but I gave up the high school curriculum because I was so fed up and I just packed my bag and traveled. I had to fall back on what I had, and that was my inborn talent. that is how it all started out but I actually wanted to be a mineralogist or geologists! once you have a hobby, you can always learn more.

‘black power / white power’, 1967

image © tomi ungerer

DB: with that kind of mind-set about freedom, when you were first creating more adult and controversial pieces of work, were you ever concerned about the effect it might have on your previous published children’s books?

TU: you have to understand that I did a lot of work in advertising, in publishing and I was illustrating all the time – it wasn’t just children’s books. my only concern was that my erotic books should not fall into children’s hands. that is really important and would have bothered me. I am not talking about the frogs in fornicon. a lot of people come up to me and say that when they were 14 years old, they saved up their money so that they could buy the frogs. I have always been involved in battles. one of my battles has always been sexual freedom. my moral principle is that you are allowed to do anything you want as long as you don’t hurt somebody else. in terms of sadomasochismo, if somebody wants to be hurt – and I met people like this – I do believe in playing out people’s fantasies and that is all. when I was releasing large volumes of my erotic work, there were more women at the signing sessions than men, and this made me feel good. women should have their fantasies fulfilled.

DB: in some of your erotic books, you published some unusual scenes with frogs in kamasutra positions and fantasy machines, what made you want to illustrate and publish these more extreme subjects?

TU: fornicon was satire, it wasn’t erotic. I did not spare the showing of certain organs because it’s the mechanisms of sex. I did an interesting book in germany called guardian angles of hell, which focuses on how I lived in a bordel on-and-off for several years. it was in a district where no peeps were allowed and only women were running the bordels. in every bordel, there are one or two dominas in a torture chamber, and this is what I did the book on. not like a reporter, but like someone who lived there. I tried to establish some rights for them. dominas spend a lot of money on their leather outfits, and I think they should be tax-deductible for instance – I worry about things like that.

‘pig heil!’, 1994

image © tomi ungerer

DB: so there is always a much deeper meaning behind all your work, even the more adult/erotic stuff?

TU: there is always an idea behind it. the women at the bordels are fantastic. they are never touched by their clients – it’s a piece of art. where a psychiatrist stops, they begin. they relieve people from their obsessions in a way that a psychiatrist wouldn’t be able to. for example, a specific client could only have an orgasm if the domina were to pull his nail off of his finger with some pliers. it sounds sick but it is better for these young boys to go there than to a psychiatrist who can’t help them. they aren’t deranged, why shouldn’t they find release somewhere if they pay for it? this is far out material, and people will think how they want. I have been told that my book was the best and most thorough one about sadomasochism practices ever published. not that that is my thing. I just lived there and met them.

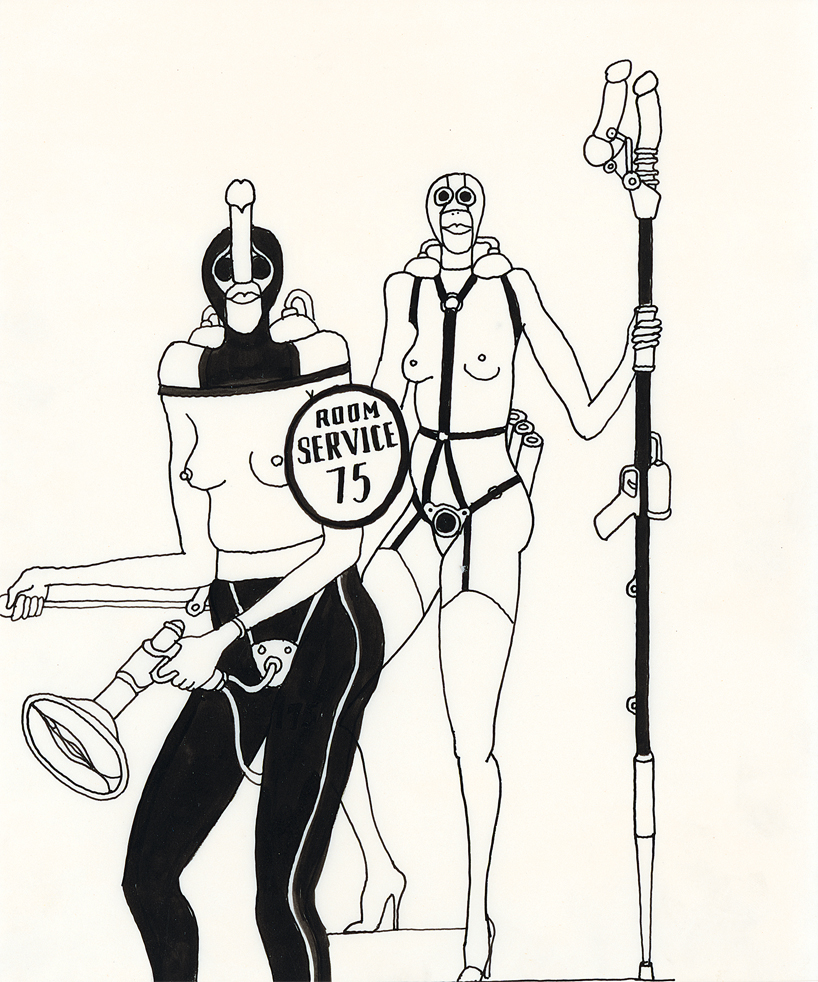

‘fornicon’ illustration, 1969

image © tomi ungerer

DB: a target for all creatives is to produce work that is timeless, and the majority of your work fits into this category. do you think this is because you base a lot of the ideas from chapters, moments, that are very relevant in your life?

TU: well, right now in france next year, there will be a big volume coming that is on all of my political work. I would say that in some of the work, none of the issues have changed. it is a matter of reading between the lines and reading what is on the wall. right now, people don’t read on the walls even though it is right there and is going to happen. history is elementary, it is only the tools you change. if you study history, history is not necessarily in the past, it is in the present. right now is history and so will tomorrow, especially with the US elections. let us have no illusions because the results and who wins, will not change anything. the split is now divided in an irreparable way, where no surgery can bring america back together again. so whether it is trump or clinton, the results will be just as damaging because the injuries have already been done. this is due to the basic lack of education in america which nobody wants to talk about, even though it is so obvious. there are electorates with no education. this is written on the wall and no one seems to be paying attention to it. by finding and using certain information that is related to the subject, I read in between the lines. once you collect these two elements, you can gather a pretty clear view on the hopelessness of the situation anyways – like the US elections. I say this because people are not going to be ready to tackle any of the major problems. it is the same with ecology right now. we could stop all the gas emissions but the changing of our climate is not going to stop because we triggered it to start with.

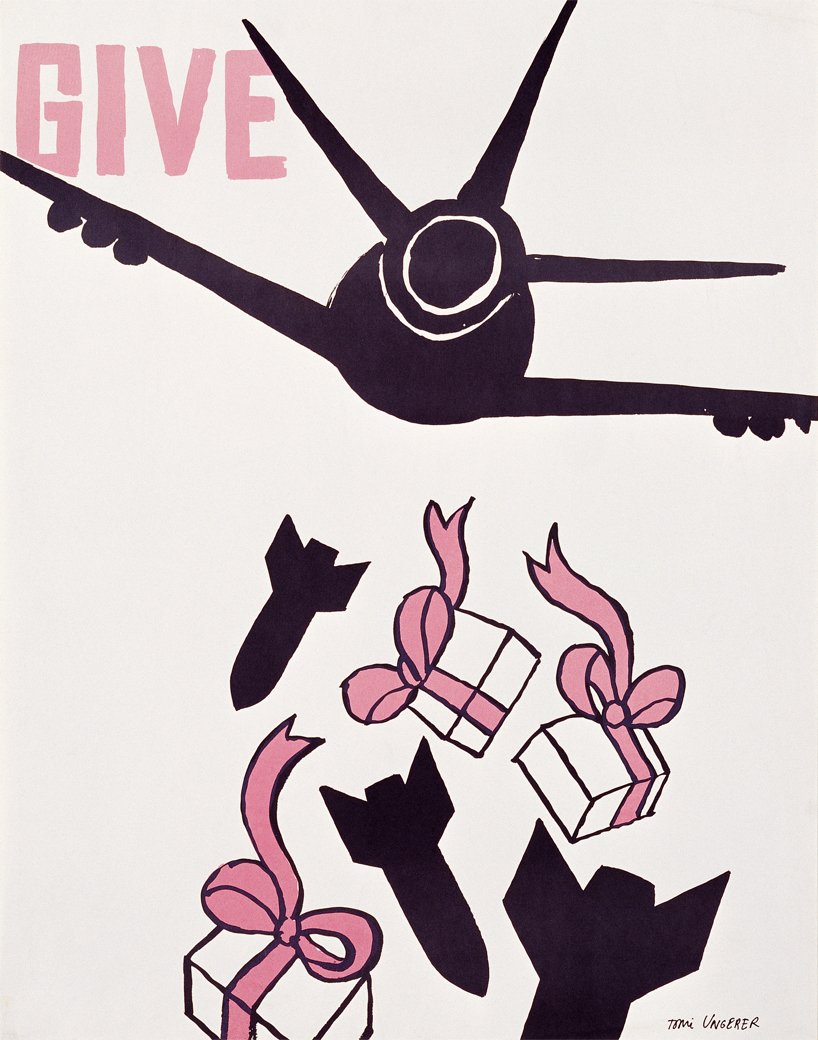

‘give’, 1967, poster in rage to the vietnam war

image © tomi ungerer

DB: do you see your next ideas being influenced by these very relevant and quite large issues of today’s worlds?

TU: I continue working all the time. my last book, ‘incognito’, which is a collage of sculptures, features everything. there is not a subject which isn’t addressed. behind every one of my stories, you will find a bigger idea.

DB: you’ve said, ‘there is no market for illustration anymore, photography has taken over’. what is the current landscape for illustrating?

TU: with the invention of the television, it was the end of the magazines, and it was all these magazines that gave all the work for most illustrators. illustrating was even in the advertising inside of magazines. now, photography has taken over everything. people do not have the time for illustrating. children’s books are one of the only outlets for illustrating now.

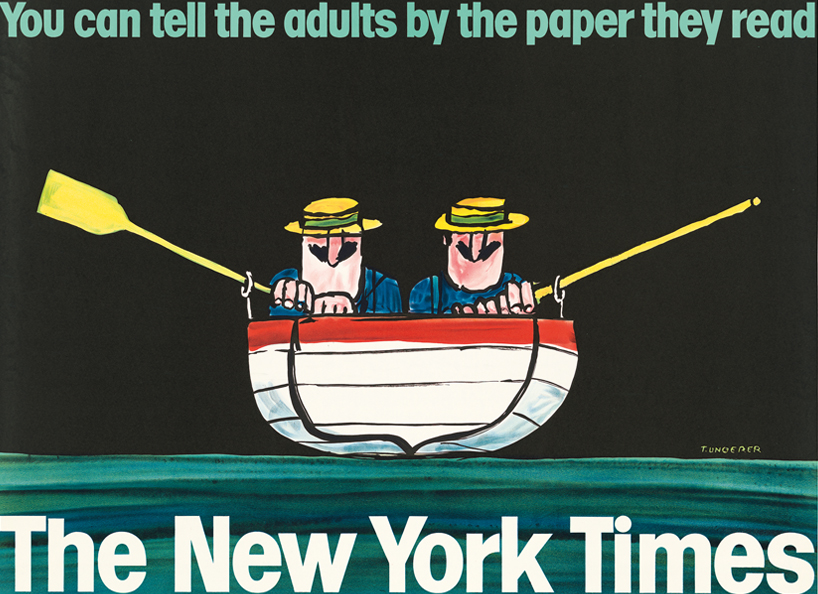

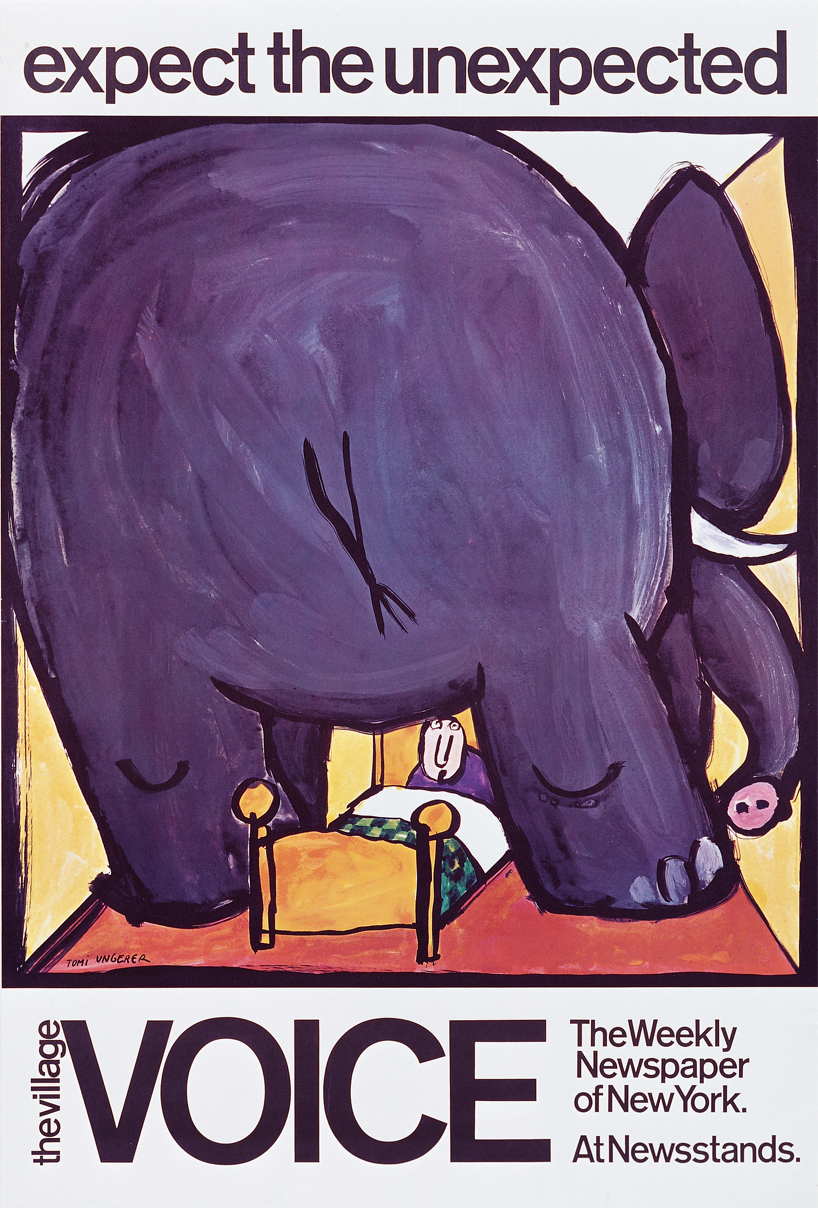

‘the village voice: expect the unexpected’, 1968

image © tomi ungerer

DB: do you read many digital magazines or newspapers now?

TU: I only read the new scientist, the new york times and also the economist. that is all I read. the economist has really good illustration ideas on the front cover. I really appreciate this quality. they are very inventive. the economist is a great example of giving illustrators a chance and making something fun. I wouldn’t say no to illustrating their front cover but it depends on the subject and whether I could get a really good idea.

DB: what advice do you have for young illustrators?

TU: write and draw. anyone can do it but do not be an illustrator for somebody else’s stories. do your own stories and try as hard as possible. it is all about a matter of endurance. every year, there is the bologna book fair and there are about 3,000 to 5,000 new titles every year. I think my books are still doing well. nowadays, when I look at books, they are drawn in a much better way technically but I was more adventurous and reckless from the beginning of my career and it has paid off. now everyone is doing their work like steinberg and myself. that is the function of artists. as a millipede, I wouldn’t have enough feet to count all of my influences, all the people who influenced and fed me. I am now at the position where I am an influence for others to take my work and go on. I wonder if there is really an original artist. an artist is only somebody who rehashes an old recipe, adds a few spices and makes a new dish out of it, which then again, will be developed on and on. this is my function and I think it is very normal that I should be copied.

portait of tomi ungerer in london, UK

image © designboom

happening this week! holcim, global leader in innovative and sustainable building solutions, enables greener cities, smarter infrastructure and improving living standards around the world.

illustration (117)

tomi ungerer (2)

PRODUCT LIBRARY

a diverse digital database that acts as a valuable guide in gaining insight and information about a product directly from the manufacturer, and serves as a rich reference point in developing a project or scheme.