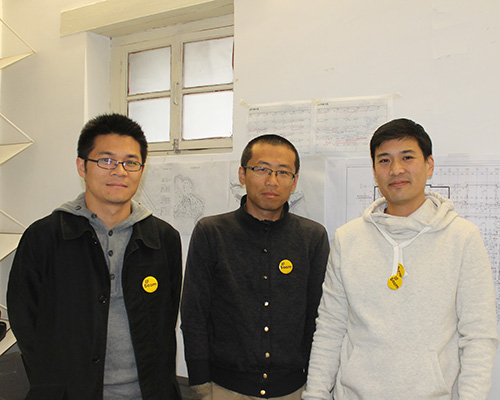

zang feng, he zhe and james shen of people’s architecture office

portrait © designboom

people’s architecture office is located in the heart of beijing’s historic hutong area, where the studio functions as a laboratory to observe, test and research designs that answer the needs of the local community. the team is led by founding members, zang feng, he zhe and james shen who initially met while working together at atelier FCJZ. their projects engage in a wide variety of building typologies and are not limited by form or scale, but instead focus on human interaction and the enhancement of people’s daily lives. the firm also runs people’s industrial design office in parallel to their architectural endeavors.

designboom spoke with co-founder james shen about the office’s influences, their ‘courtyard house plugin’ presented during beijing design week 2014, and his vision for the future of architecture in beijing.

the ‘pop up canopy’ installation in dashilar during beijing design week 2013

see more about this project on designboom here

designboom: how did people’s architecture office begin? what were its core architectural intentions?

james shen: well we were all co-workers when we worked together at atelier FCJZ for yung ho chang, an architect based in beijing. two of us were also his students: zang feng was a student at beijing university; and I was his student at MIT — he taught at both places. he was the head of the department at both institutions, so he had a profound influence on our education. we all met while working at his office and ended up leaving at the same time, which wasn’t planned. it just happened that way.

when we started people’s architecture office, it was really something we thought we could try. we had no idea, no big plan, no finances, no projects. we just thought we could give it a go, and didn’t really have too much to lose. the economic situation was already becoming worse, and the hey day of chinese building had already passed, but in any case we wanted to try.

in observing the way other offices produced architecture, we developed our approach. we found that often there was little to no emphasis on the component of the person using the building or the people around the buildings. we thought maybe we could start from that point of view and work from there. all of our designs are centered around people and so that’s where our firm’s name came from.

the pop-up structure acts as a tree to shade the courtyard below

DB: how has your practice changed over the years?

JS: in terms of our core concerns and approach, not much has changed. our philosophy has always been that we wouldn’t limit the types of projects that we did, in terms of building typology. it didn’t matter if it was a museum or library, shopping malls or parking structures, and these days even toilets… having a positive social impact is not something that is necessarily dependent on the building type. in fact most buildings are not libraries or museums, for a lot of people shopping malls are a much bigger part of their lives than a library or museum.

unfortunately, today many public spaces exist within private developments, so these require architects to design them and hopefully with good, innovative ideas. not in terms of form, but innovative ideas as a means of engaging society, improving our urban condition. we’re an socially conscious office, and we want to have a positive impact, although we acknowledge architecture has a lot of limitations… we’re not going to solve problems in a very direct way, but the effects of architecture are very clear. its negative effects are also very clear from pollution to traffic to our living conditions, so if the negative effects are clear then there’s definitely a lot of potential for positive effects.

especially in a place like china where things are changing so quickly and changing so drastically we’d like to participate in a way where we can help steer things, even if it’s a little bit. the project type is not something that we limit ourselves to, but the clients are really important. you really need a client that’s open minded that’s willing to think of problems in different ways.

‘juxing tower showroom’ in which the firm has envisioned the space expanding through reflecting boxes

see designboom’s coverage of the project here

DB: who or what have been some of your biggest influences to date?

JS: we’re influenced by quite a lot of people. I mentioned yung ho, as we all came from his office so he’s had a substantial influence. I think ai wei wei has had a strong influence on us. though he is considered an artist, he’s also realized buildings and actually we consider him one of the best architects in china… there are a lot of theorists that influence us: robert venturi, colin rowe — a lot of people whose theoretical approach has been extremely important, even though some of them never built anything. also groups like archigram, who had amazing ideas that were never actually realized have had a strong influence on our work.

actually what’s extremely influential to us are certain projects more so than particular architects, because even the best architects have some successful projects and some not so successful. for example, the brazilian architect lina bo bardi completed an amazing cultural complex called SESC Pompeia – it was the approach that she took which made it a successful outcome. she moved her office to the site and remained there for the entire duration of the project. it was an old factory site similar to 798 in beijing that was already becoming occupied in an informal way, she helped to transform it into a more substantial cultural center and it’s been quite a success. she was able to engage in between a top down versus bottom up-type approach and I think that’s actually where an architect can be of some help. we can learn from and engage in the positive and negative side of things, but if we can also be active in that middle part, then that’s a pretty ideal situation.

there are a lot of other good projects, there’s a housing project called ‘previ’ and it was in lima I think in the 60’s… it was an international competition and one of the winning designs was by Fumahiko Maki, Kiyonori Kikutake, and Noriaki Kurokawa of the metabolists. it was a government project and there was a lot of local participation – they provided a platform for people to add to or change later on. you see more of those types of projects now, where architects provide part of a building and residents can go on to customize it on their own.

the showroom is defined by a relationship of doubles

DB: could you describe your aims for the ‘courtyard house plugin’ that was presented during beijing design week?

JS: our intention was for it to be a solution on an urban scale, it’s a systematic one that can be applied to many similar situations, so it’s not a one off thing. partly how we’re able to do this is with this prefab panel that we’ve developed… it’s not something you can find on the market. we started by figuring out how to build with this new material to the production of it — the manufacturing involves customized molds and it’s then shipped on site. the panel itself is 70mm thick and has the structure, insulation, waterproofing, wiring and plumbing integrated into it, so there’s very little manual labor involved.

this means you’re able to mass produce these with high quality, and at high quantity with low cost – what costs the most and the biggest problem with quality is the manual labor. we’re able to really minimize a lot of construction issues on site. instead of taking 2 or 3 months to renovate, we take a couple of days. instead of needing electricians and plumbers and a construction crew, anyone can build this. you don’t need any specialized tools, you just need a hex wrench. there’s a locking mechanism that’s integrated into the panels that are molded together, and with one twist you can connect all the panels together. we’re able to simplify this whole construction process and make it affordable and feasible.

the ‘courtyard house plugin’ was completed as a pilot project for dashilar platform

see designboom’s coverage of the project here

DB: in developing the ‘courtyard house plugin’, what do you think is the future of the historical hutong structure? what would you like to see happen in terms of architecture and urban growth in beijing?

JS: people talk about historic preservation, but actually what I think is more important is not necessarily the buildings, it’s that you’re able to preserve a type of interaction between people. the life you see in these historic areas is not primarily because they’re old, the people interact this way because of the urban make up, the diversity of activity… you have shops and residences and all kinds of different programs, including small studios, offices and markets. these different programs are well integrated and it’s quite varied… the architecture is on a human scale. when you introduce things such as highways, ring roads and train tracks, then you really disconnect a lot of these parts of the city and that produces a certain amount of trauma in these areas.

we’d like to see more ways of connecting neighborhoods and places together, but we recognize that there will be these disruptions – highways and train stations are of course necessary, but it doesn’t mean that the cities have to be disconnected. I think there are intelligent ways to deal with these situations. a city needs to modernize and the economy needs to grow, but we these things don’t have to be in conflict with each other.

the ‘courtyard house plugin’ is an easy-to-install solution to upgrade hutong buildings

DB: personally, what are you fascinated by outside of the architecture profession and how does it influence your work?

JS: there are so many things, but most immediately for us is our other practice. we are an architectural office, but we’re also a product design studio and it’s a discipline that is fairly different to architecture and it’s really influenced our projects, especially the ‘courtyard house plugin’. products can be global, they are things that people use everyday, what you sit on, what you sleep on, what you use to eat and so on – they’re are all mass produced items which generate the economy, so that’s something that’s close to us. but aside from that, all kinds of things: fiction, music, movies… it’s important to keep ourselves close to these other creative fields. we actually don’t really enjoy talking to too many architects you know… going on trips and seeing architecture. I mean we’re located here so we can get a mix of all kinds of influences.

installing the prefabricated panels for the ‘courtyard house plugin’

DB: what advice would you give to students and young designers?

JS: there’s a lot of this obsession on technology, there’s a lot of obsession on form and coming from MIT our environment is full of technology with people doing really innovative projects. people celebrate technology as if it’s going to change a lot of things, I think the media really latches onto this idea as well, but in practice a lot of this is really just fluff — this parametric stuff and 3D printing. my bachelors was in product design and I worked as a product designer for years. we used 3D printers in our practice 15 years ago. it’s something that’s very normal. there’s nothing special about it and it doesn’t really integrate itself so much into the design process. ideas are still going to come from understanding people, and understanding their relationships with their environments. it’s not going to come from writing some code and using some new software.

‘river heights pavilion’ located in china’s shangxi province

see more about this project on designboom here

DB: how do you keep your ideas fresh?

JS: to keep us fresh we really emphasize our design process and it’s something that everyone who comes here has to spend a bit of time getting accustomed to. we don’t separate or subdivide departments, we don’t have CAD people and we don’t have 3D modeling people, everyone is able to use practically everything. there’s not one technology or piece of software or making things that we don’t understand or know how to do, so that means when we go to the site we can gain the respect of not just the clients, but construction workers. when we go to factories we know how to use the machines — you can’t be afraid to get your hands dirty. something that I really dislike about china is that there is a fairly distinct social stratification, so that if you went to university it means that you’ve never done any kind of manual labor, it’s not looked upon highly. if you’re a designer you’re this kind of intellectual and it’s very clear. it’s really gets in the way of our work sometimes, because people see that we have our hands dirty and it’s hard for them to understand that we’re the principles of these companies.

the more of that kind of separation there is, the less you’re able to produce meaningful things. so, embedding ourselves into the processes and these systems is the same as embedding ourselves in a neighborhood and working in the city. the main thing is not separating the types of buildings we do. it’s very difficult to introduce ourselves to people because they always ask on those terms, what kind of building are you involved in.

offices and the roof terrace overlook the garden at ‘river heights pavilion’

architecture in china (1884)

people's architecture office (38)

PRODUCT LIBRARY

a diverse digital database that acts as a valuable guide in gaining insight and information about a product directly from the manufacturer, and serves as a rich reference point in developing a project or scheme.