design for death living by Ancunel Steyn from south africa

designer's own words:

Introduction

For many of us the cemetery is not where we choose to unwind from a busy day or find inspiration for a more meaningful life. You might think it is obviously not, but cemeteries used to be our parks and they have the potential to become even more than that: a place where life is lived, where people of all ages find inspiration for life and prepare for death, where healing is not a mere suppression of emotion but a process that engages body, soul and spirit.

One day, due to heavy traffic I had to take an alternative route in the new City I moved to. This route led me unexpectedly past a massive, morbid place of death. It reminded me of a writing of Corner on dead landscapes as ‘stillborn landscapes’ or “corpselike constructs of such obscene explicitude that noting is left to imagination. In such closed and final works, nature, memory, myth, and theory come to an end. In the topography of pure reason, homogenous and without hiding places, the enigmatic encounter with things and places is flattened without depth or horizon. Here, humanity is reduced to a corpus of automations, alone in a world where bodies exist only in saturated states of pure presence, without even the faintest glimmer of a possible absence [, death]” (Corner, 1991). I felt saddened for those whose bodies have tragically ended up in this place and for those who visit them here. But more than this I was overwhelmed by the size of land almost filled up with the dead of our city lying there on the outskirts, almost forgotten and without other use.

Multifunctional

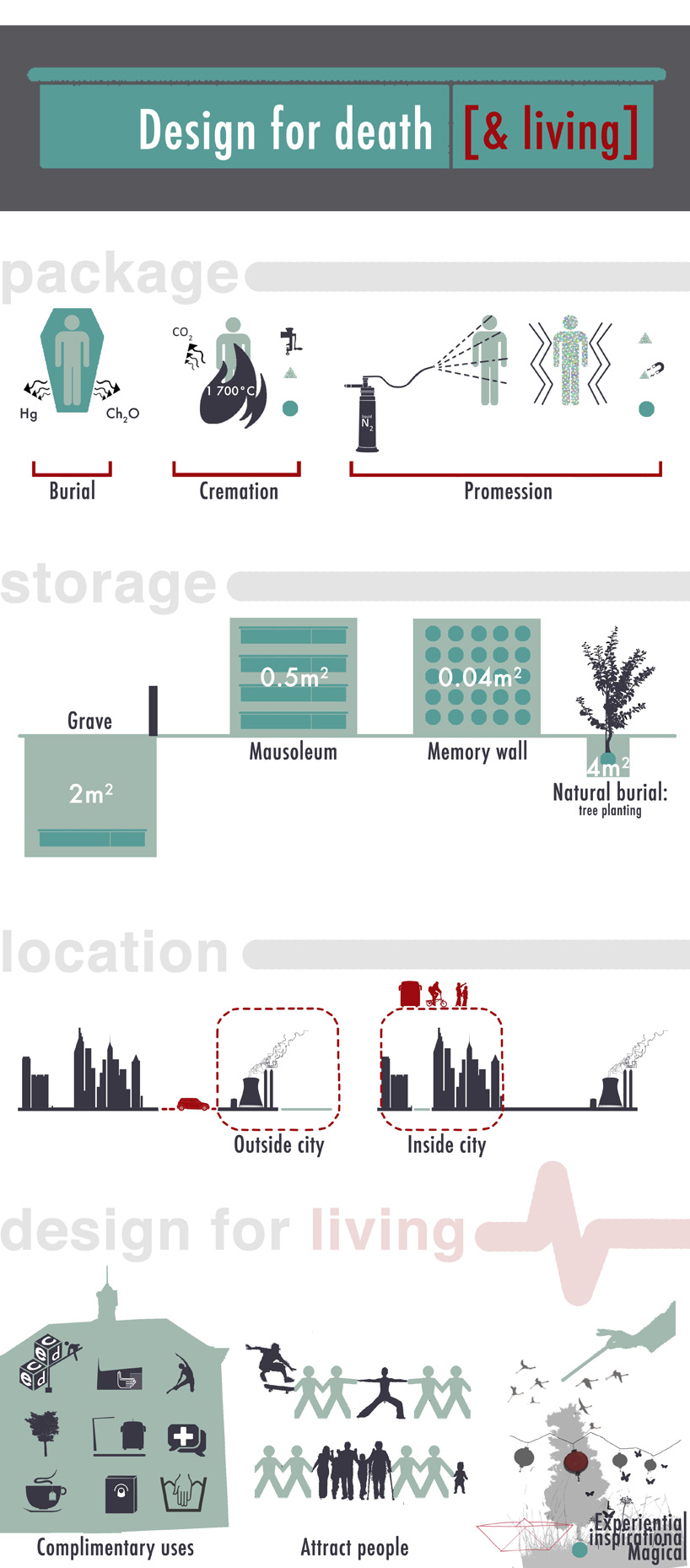

Land is not a non-renewable resource. Severe pressures are on governments to find suitable land for housing, urban agriculture, to conserve the environment, provide parking, sportsfields and cemeteries. It makes sense to apply the strategy that will encourage people to make better use of resources namely to first reduce then reuse and recycle.

The question is, how can we reduce space required to store the dead? Worldwide creative minds are joining heads to debate ways to decrease the amount of land required for burial (Worpole, 2003).

Cremation and an arguably greener option namely promession reduces the size of the corpse from an almost 2m long casket to the size of a tissue box. It is not difficult to picture the space savings if one was to pack out a hundred of each in rows of twenty. Now stack the five rows of tissue box sized urns on top of each other to mimic a wall of remembrance. One can space a number of these stacked urns – lets call them memory walls – in rows with circulation space in-between for a similar effect to the isles in a retail outlet.

Add vertically to this metaphorical retail outlet offices, parking and residential units and the development not only saved land and money, but also clustered together a number of uses that support each other.

Similarly storage places for the dead can be combined with complimentary uses to not only achieve a space saving, but also bring about emotional and spiritual benefits for visitors. Clustering of these landscapes with other complementary uses and around transport nodes will make them more accessible and attractive to various users. Less vandalism and closer travelling distances holds further financial and resource savings.

Highly accessible, integrated

Distant, mono-functional cemeteries over decades became symbols of insecurity (Setplan, 2003) and threat - an area where vandals and thugs roam. Insecurity became such an issue that it is stipulated that the living is only allowed to visit the cemetery during stated hours, children under the age of 12 must be accompanied by an adult and that the cemetery may not be used as a thoroughfare.

Western views and negative perception of the cemetery had it’s origin at the end of the 19th Century when Haussmann proposed to close down all cemeteries in the city and move the bodies to the municipal cemeteries to be constructed outside the city boundaries. His proposal was based on health reasons and to meet his objectives of remodelling the boulevards and streets of Paris. This also met his personal aspiration of a perfect world free of death and dirt. The topic “Death” was even forbidden in conversation that took place in his presence. At that stage the cemetery was part of the city and a strong connection existed with the living. Around 70 000 people were visiting the city cemeteries per week. Haussmann did not acknowledge the central place cemeteries rightly held in the urban fabric and hearts and minds of people and denied the dead a place in the new city or quite frankly any place in view of people. His goal was to move corpses out of the city by train during the night to be buried outside the city as quick and invisible as possible. Keeping the context in mind, the inhabitants’ reaction to Haussmann’s resolution was no surprise: “Pas de cimitiere, pas de cite!” translated as “no cemetery, no city” (Open Essay #1: The City & The Cemetery, 2009).

The Haussmann resolution and the establishment of a new cemetery on the outskirts of the city, led to descriptions like that of Victor Fournel in 1870. Fournel described the cemetery as “a single distant necropolis, a vast and glacial funereal Siberia where the dead would be transported like convicts in repulsive conditions to rest in solitude, exiled both from the hearts and eyes of those who love them” (Burton, 2001, p. 134). This distant necropolis became a monument for society’s isolation of the dead and even in some instances the denial of death.

We created a conviction that burial activities are seen as separate to everyday life activities. I argue that spaces for the dead must form part of the Civic Structure or ‘Res Publica’ (Krier, 2002) and encourage a return to the idea of the post 7th Century and pre Haussmann situation where the centrally located churchyard was used for burials. Similarly to the churchyard, the landscape where human remains are stored is highly accessible to pedestrians and those using public transport. The landscape is accessible to young and old and, like a well-designed high street, become an outdoor classroom for children.

Death awareness: benefits and method

In a landscape where the dead is memorialised and their remains stored in beautiful ways and pleasing settings, visitors and passersby are presented with a familiar environment where they can share their feelings, thoughts and uncertainties about life and death.

Suggested activities that can be combined with such landscapes as described above, and hypothetically explored in the sketch plan, includes:

• Self-service kiosks – explained below

• Early Childhood Development Centres

• Transport related facilities

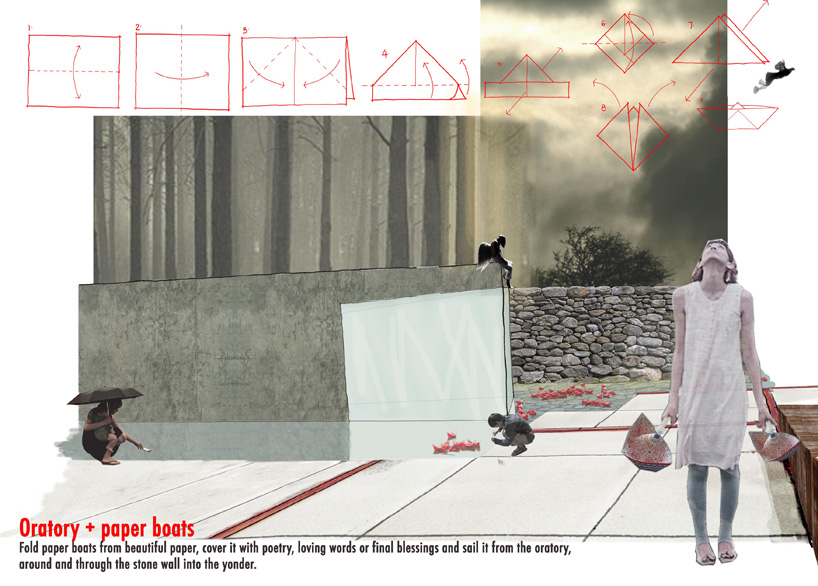

• Oratory (small chapel for private worship)

• Public spaces, including green spaces

• Coffee shops, restaurants and tea houses

• Therapist consultation rooms

• Yoga studio

• Baptism pool

• Place for ritual cleansing

This setup counteracts the over-emphasis of rational thinking about death as stated by Camus (in Ward, 1996: 27): “Since men cannot cure death, they have made up their minds not to think about it”. We cannot wait to be confronted by death before we prepare children and ourselves for it. In this outdoor classroom even children can see how others are buried and learn that mourning is not a weakness, but a psychological necessity (Gorer 1965 as cited in Ward, 1996, p.3). Thanatologists concur that educating children about death when they are developmentally ready assists in reducing fears about death and dying. This approach therefore suggests that the unconscious should be allowed to express itself freely through an array of activities or places where creative play is encouraged in the landscape. Most children learn best through experience and play. This landscape thus becomes a playground that informs of loss and aids in healing.

Technology and wrappings of the remains

Cremation and promession are two ways of transforming a corpse into a smaller volume with a wider range of storage options.

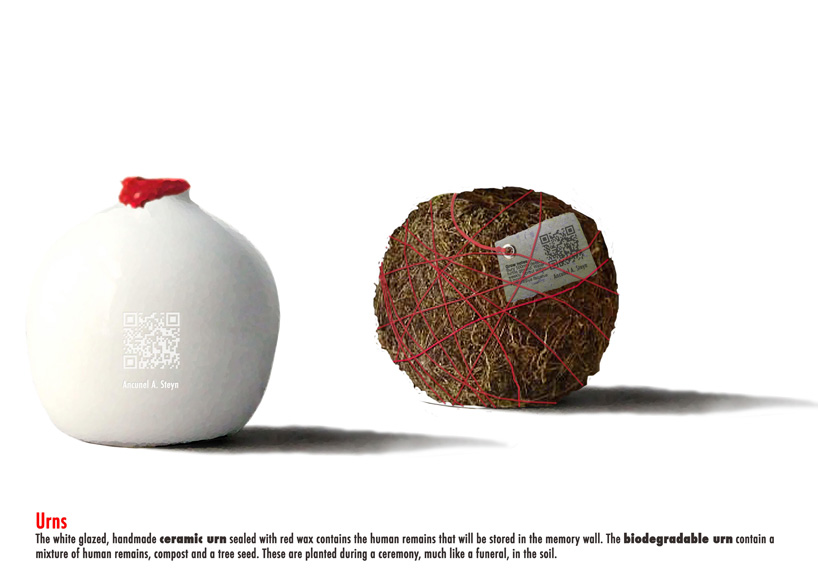

Handmade ceramic urns sealed with red bee wax contain human remains that will be stored in the memory wall. COR-ten steel covers are fixed to precast concrete modules to protect the ceramic urns. COR-ten with its rusty appearance is a material chosen to emphasize the transient nature of humans. Plants are grown in cavities in the wall and replace the more common practice of placing picked flowers and leaving them to die. The stone cavities are also perfect for leaving stones. When visitors scan the QR codes on the COR-ten covers with their phones, they gain access to a customised memory film or photo slideshow of the diseased. The memory film and slideshow can be created and loaded at the sel-service kiosk and a privacy setting allows you to choose how much of the information is made visible to the general public and how much of it is restricted to specified users that may be friends and family.

The biodegradable urns contain a mixture of plant-nourishing human remains, compost and a tree seed. The urn is buried during a ceremony, much like a funeral, in a shallow grave in the soil and watered to bring forth life in a different form. This burial method can be used to establish an urban forest, rehabilitate a natural area or green a park with trees. For illustrative purposes the art gallery site on the hypothetic plan is selected to employ the use of this method for the establishment of an urban forest setting. Each tree will be mapped with GPS and visitors will be able to find them using their smart phones or hard copy maps printed at the self-service kiosks.

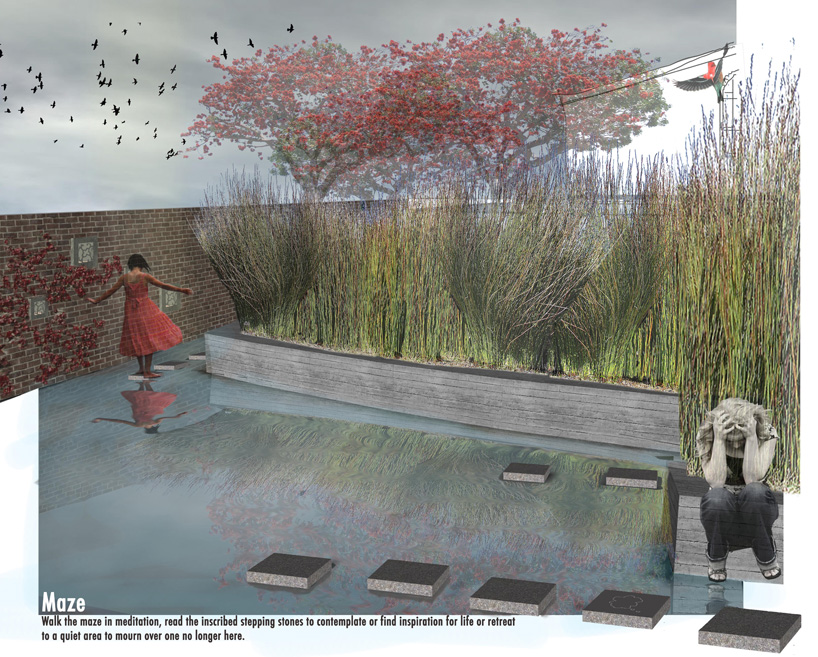

Those who whish to sprinkle the human remains elsewhere can consider a plaque whereon a question or quote about life can be inscribed. The inscribed plaque will replace a stepping-stone in the maze. The living can walk the maze in meditation and use the questions to guide them along the path.

Self-service kiosks offer a do-it-yourself alternative for everything from the promession process to choosing an urn, making a booking for the oratory, create (or order local community made) paper boats for sailing around the oratory into the yonder and creating or listening to a memory film or photo-play of the diseased. The self-service kiosk will further offer the user the choice of carefully selected background tunes for music therapy to enhance the healing process while they plan for the memorialisation of the diseased.

Conclusion

I therefore concur with the thought that that the preparation for death is part of the preparation for living; and therefore for life and death once again to become inseparable.

Reference:

Burton, R. 2001. Blood in the city: violence and revelation in Paris, 1789-1945. USA: Cornell University Press.

Corner, J. 1991. A Discourse on Theory I: “Sounding the Depths” – Origins, Theory and Representation. Landscape Journal. 10(2): 61-77

Krier, L. 1992. Architecture and Urban Design 1967 – 1992. London: Academy Editions.

Open Essay #1: The City & The Cemetery. 2009. Retrieved May 2011 from The Accounts: http//theaccounts.tumblr.com.

Setplan. 2003. Metropoligan Cemetery Study. City of Cape Town, Directorate City Parks and Nature Conservation, Cape Town.

Ward, B. 1996. Good Grief: Exploring Feelings, Loss and Death with Under Elevens. A Holistic Approach. (Second Edition). Pennsylvania: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Worpole, K. 2003. Last Landscapes: The Architecture of the Cemetery in the West. London: Reakton Books.

design for death [& living] infographic hypothetical sketch plan

hypothetical sketch plan memory wall

memory wall oratory and paper boats

oratory and paper boats maze

maze urns

urns