borders, history & landscapes at National Academy of Design

As the National Academy of Design approaches its 200th anniversary, a deeply reflective exhibition titled Past as Prologue: A Historical Acknowledgment, Part I, opened at the Academy’s new space in Chelsea. This exhibition, presented by Chief Curator Sara Reisman and Associate Curator Natalia Viera Salgado, explores the intersections of landscape and territory during the 19th century, inviting viewers to consider how these themes resonate within today’s cultural and political landscape. This first show of a two-part series will be on view until January 11th, 2025.

The artworks on view — from portraiture to landscapes — span nearly two centuries, featuring the Academy’s historical collection alongside contemporary pieces that engage with complex histories of U.S. expansion, colonialism, and shifting ideas of identity and belonging. As Reisman shares in an interview with designboom, Past as Prologue aims to offer ‘a progression in terms of how art was an instrument of nation-building but evolved into an expression of culture…more aligned with contemporary art as we know it.’

install view, image © Etienne Frossard, courtesy National Academy of Design

past as prologue: Interrogating America’s Past Through Art

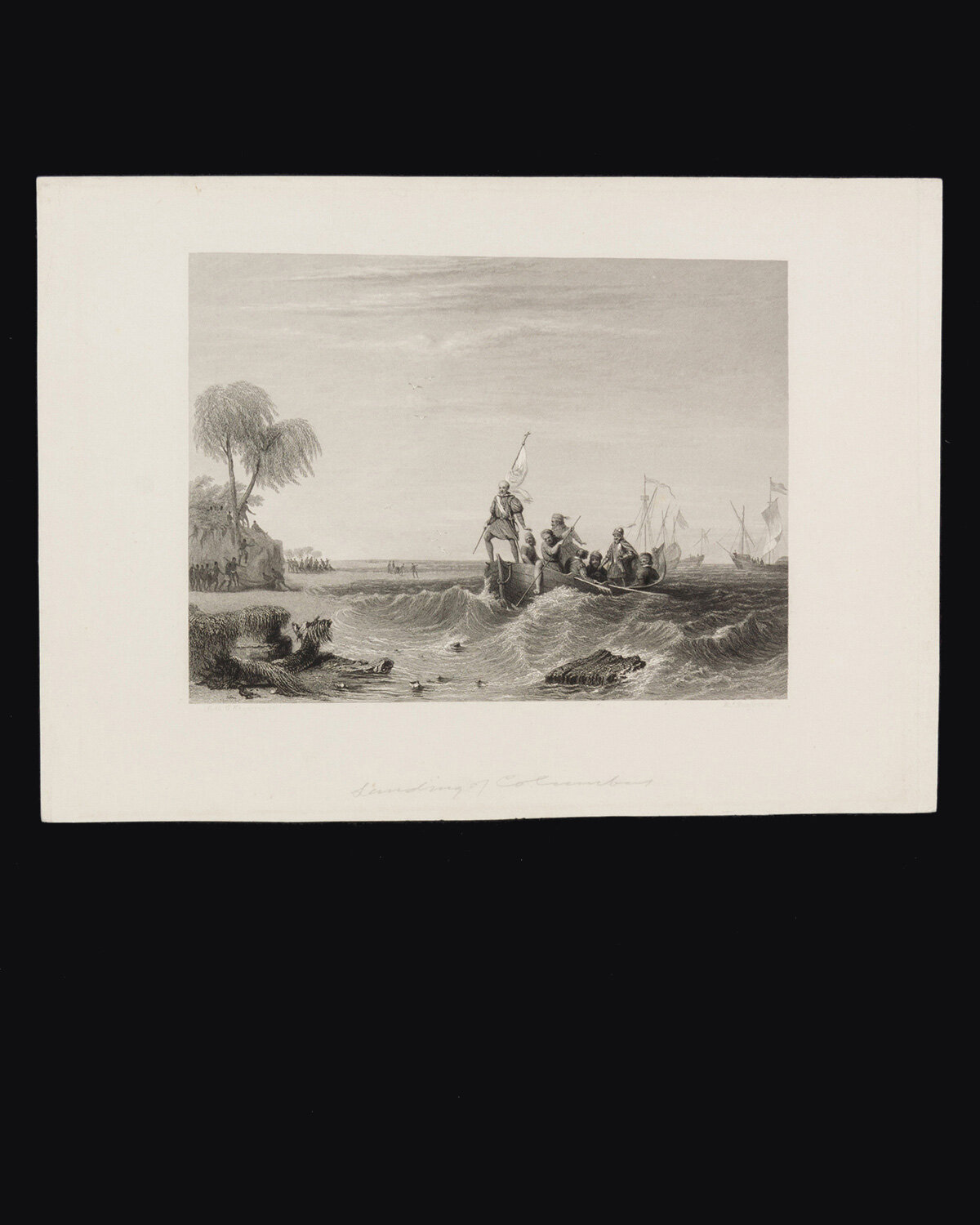

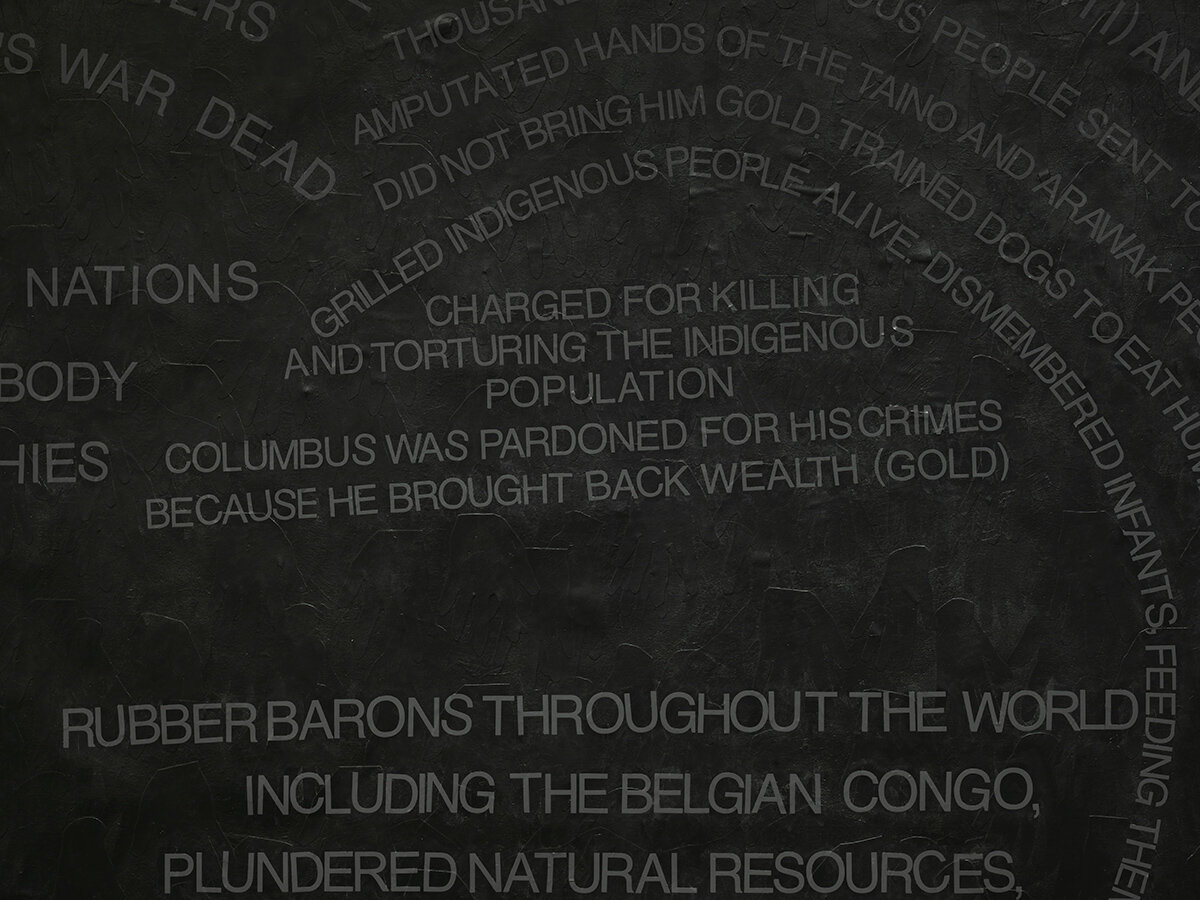

With this upcoming exhibition at New York’s National Academy of Design, the co-curators intertwine historical works with modern reinterpretations, sparking dialogues that challenge traditional narratives. For instance, Reisman highlights an early engraving by Moseley Isaac Danforth, The Landing of Columbus, paired with Howardena Pindell’s contemporary piece, Columbus. These works starkly contrast each other, with Danforth’s illustration representing the so-called ‘discovery’ of America, while Pindell’s piece addresses the atrocities of colonization. By displaying these works in dialogue, Reisman demonstrates the trajectory of American art from its role in forming national myths to serving as a medium for critical reflection. ‘This arc of art history and American history,’ Reisman notes, ‘is emblematic of the Academy’s evolution.’

A focus on landscapes, both idyllic and exploited, offers a nuanced portrayal of the American experience. Traditional Hudson River School landscapes are set alongside works by contemporary artists like Sonny Assu, whose interventions on historic landscapes disrupt the myth of manifest destiny. This type of juxtaposition calls into question the environmental impact of U.S. expansion, as well as its cultural repercussions. By engaging viewers with these contrasting visions of the American landscape, Past as Prologue lends a space for critical dialogue around issues of extraction, migration, and Indigenous rights. Read the full interview with Chief Curator Sara Reisman below!

install view, image © Etienne Frossard, courtesy National Academy of Design

dialogue with chief curator Sara Reisman

designboom (DB): Past as Prologue explores significant moments in U.S. history through art. What curatorial strategies did you use to create a dialogue between the historical works and the contemporary pieces in the exhibition?

Sara Reisman (SR): Working alongside associate curator Natalia Viera Salgado, we tried to create a dialogue between the 19th century — which is when, in 1825, the Academy was founded — and more contemporary artistic practice, to give a sense of a progression in terms of how art was an instrument of nation-building but evolved into an expression of culture in a way that is more aligned with contemporary art as we know it. The two groups of work where this national identity becomes most apparent is in portraits and landscape.

A few key examples are an engraving of a landscape — or really seascape — of The Landing of Columbus by Moseley Isaac Danforth from the mid-19th century. This tiny work is an illustration of the victorious explorers’ ‘discovery’ of the new world. It’s installed across the gallery from Howardena Pindell’s Columbus, 2020, which is a maximally scaled black canvas, layered with cut outs of hands, black hands layered on a black background, with a pile of black silicon hands on the floor, and above text detailing the atrocities of colonization, including the Spanish explorers gruesome abuses of the native people they encountered. Both of these artists — Danforth and Pindell — were elected by their peers into the Academy. Danforth in 1826 and Pindell in 2009. The two artists are one example in the show of this arc of art history and American history too.

install view, image © Etienne Frossard, courtesy National Academy of Design

DB: In Part I, you highlight themes of landscape and territory during U.S. expansion. How do the works in this section challenge or complicate traditional representations of ‘manifest destiny’ and the formation of the United States?

SR: I think this is partially addressed in the example of the dialogue between works by Danforth and Pindell. Maybe a more direct critique of land and landscape comes through bringing paintings by Hudson River painters like Frederic Edwin Church and Louis Remy Mignot into dialogue with artworks by contemporary artists like Sonny Assu and Enrique Chagoya who are working with landscape but in a more conceptual sense. The Hudson River School painters generally depicted the landscapes as relatively uninhabited save for a figure, or none at all.

install view, image © Etienne Frossard, courtesy National Academy of Design

SR continued: Both Assu and Chagoya intervene on historical paintings of early American landscape by adding cultural references into the image that disrupt the myth of manifest destiny. Assu’s work Home Coming, (2014) is based on the late Irish-Canadian artist Paul Kane’s 19th century painting Scene Near Walla Walla (1848-52) which depicts a group of indigenous people in the landscape to which Assu added an abstract indigenous form floating in the sky. I see this as a form of indigenous futurism, imagining the landscape that doesn’t conform to imperial sensibilities. Chagoya’s Detention at the Border of Language (2019) is a reinterpretation or remaking of German-American artist Karl Wimar’s The Abduction of Daniel Boone’s Daughter by the Indians (1853). Using Wimar’s narrative as a starting point, Chagoya conflates 19th century racist cultural fantasies about the savage Native with the politics of the U.S. border in the 21st century.

install view, image © Etienne Frossard, courtesy National Academy of Design

DB: The exhibition includes both idyllic depictions of nature and works that address the impact of extraction and exploitation. How do these contrasting portrayals of the American landscape contribute to the broader narrative you are constructing?

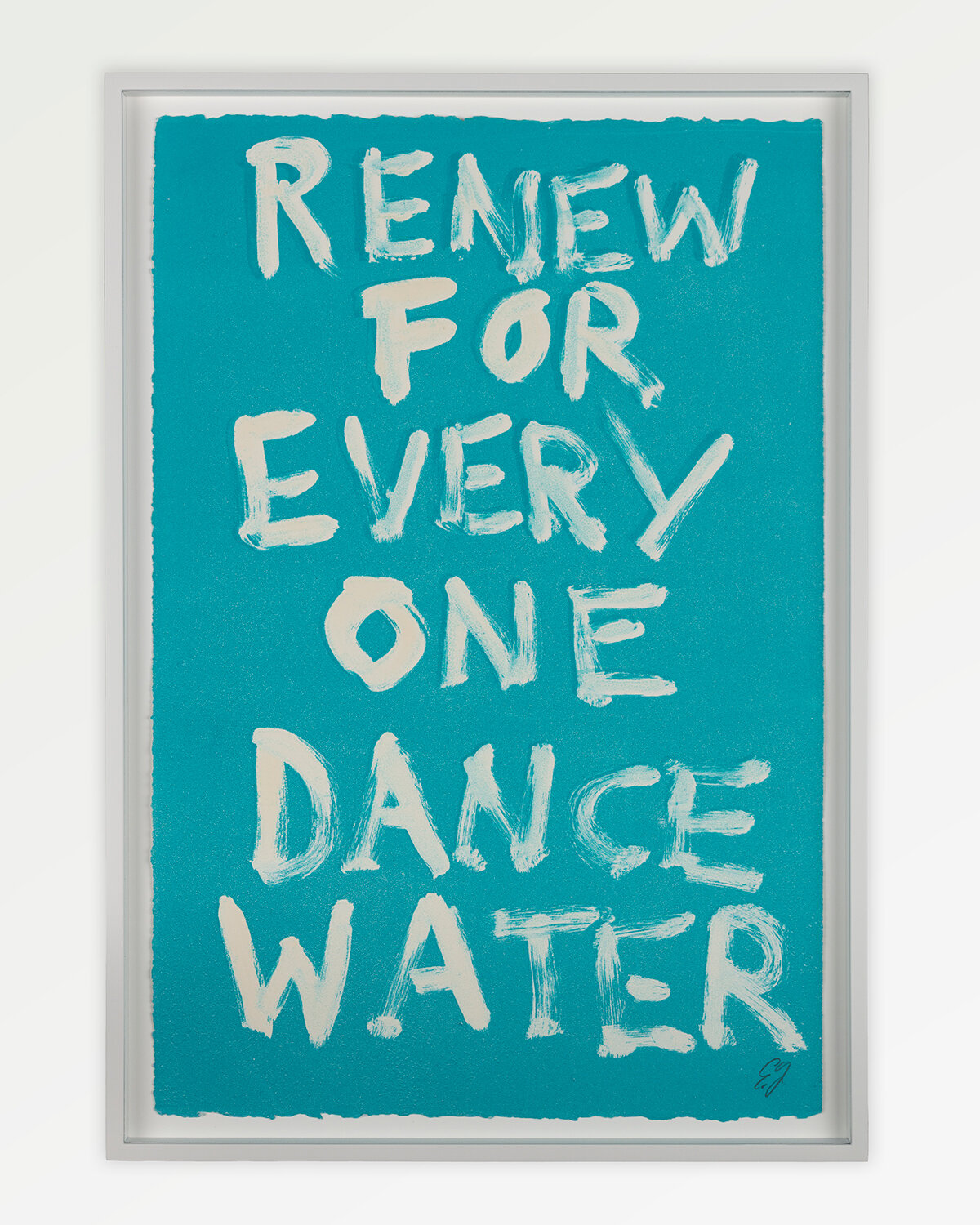

SR: Two of the works that take up extraction and exploitation in unexpected ways include Mary Miss’ Connect the Dots (2007) and Hock E Aye Vi Edgar Heap of Birds’ Renew For Every One Dance Water (c. 2018). Mary Miss’ work is an installation of blue dots around the gallery that helps visitors to envision the scale of rising water levels due to climate change in a way that is minimalist yet immersive. Heap of Birds’ monoprint is a text based piece that reflects on the importance of and respect for water that are upheld by Indigenous communities across the United States.

These two artists have long held practices that relate to landscape, drawing from different traditions that intersect in their projects that have materialized as earth works. Both of their works on view are imbued with activist sensibilities, Heap of Birds using text and Miss using a simple formal intervention. Together they move away from landscape art as a literal representation, to offer boldly conceptual expressions about the landscape, and in each of their cases, water as landscape.

install view, image © Etienne Frossard, courtesy National Academy of Design

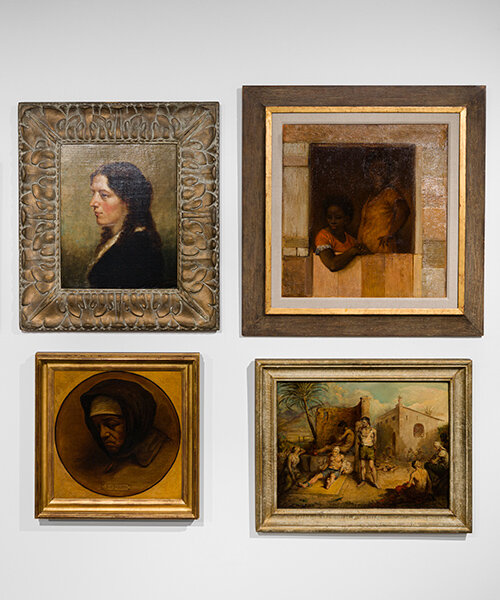

DB: Portraiture plays a key role in this exhibition, especially in how it has historically represented Indigenous, Black, Brown, and female subjects. What do you hope audiences will take away from seeing these early portraits alongside contemporary works created by artists from these communities?

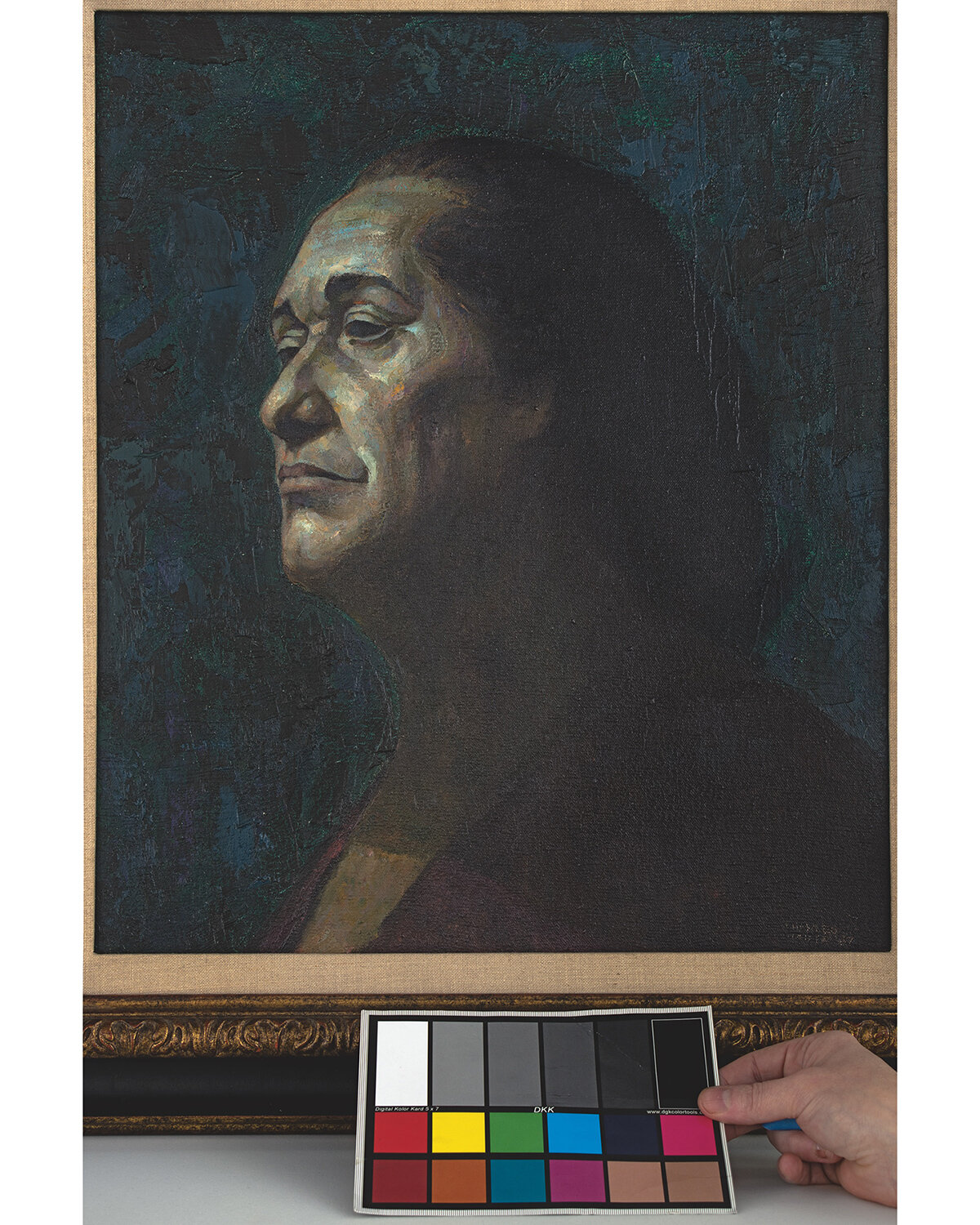

SR: Something I tried to address in the exhibition essay was how portraiture was so important because there was such a market for it in the 18th and 19th centuries. Of course there are the obvious portraits of white men in our collection, in large part because Academicians were required to submit a portrait to the Academy’s collection as part of their membership. But what becomes interesting is to see a shift in who is being represented in these portraits, for example Elihu Vedder’s Jane Jackson, Formerly a Slave (1865), or Charles Wilbert White’s The Matriarch (1967).

Maybe most prominent in his time was Eastman Johnson, whose work in the show Negro Boy (c. 1860-61) is an example of genre painters of the period expanding who was represented in early American art. Some of the later works, like White’s The Matriarch is a sign of progress in the sense that he was an African American artist elected into the Academy, so the idea of who is shaping national identity and contributing to art history through portraiture and image making was no longer limited to just a privileged class of white men of European descent. The National Academy is old fashioned — historically so — in its structure, but the artwork produced has shifted and continues to move away from these early archetypes.

install view, image © Etienne Frossard, courtesy National Academy of Design

DB: Given that this exhibition serves as a lead-up to the National Academy of Design’s 200th anniversary, how do you see the Academy’s role evolving in the coming years, especially in terms of addressing issues of race, identity, and political action in art?

SR: Because the Academy is led by the artist and architect members, it’s hard to say exactly how it will evolve, but looking at the last few cycles of National Academicians-elected into the Academy, one can see movement in terms of the kinds of artistic and architectural practices that are being recognized. One thing we are bringing back in the next year and half is a show called the Artist’s Eye which used to happen every few years, with artists making selections from our historic collection. My hope is that we can involve the Academicians in more exhibitions and programs that really stretch the Academy’s exhibition-making practice, to the extent that socially engaged and pedagogical models can be supported, so that we can engage with more expansive definitions of art and design.

install view, image © Etienne Frossard, courtesy National Academy of Design

SR continued: I also believe we’re well positioned to support critical discourse around race, identity, and political action as they relate to art through exhibitions and otherwise because we are not monolithic in our political identity as an organization. Because our collection was assembled primarily through donations of ‘diploma works’ that the artists select from their own practices to represent themselves in this two-hundred year old archive, we can look critically at our history and the visual culture that it contains without offending an acquisitions committee (which we don’t have as part of our structure). I will say that criticality for me is a sign of investment, so to be critical of our history and to learn from it is not not about tearing it down, but about cultural accountability.

install view, image © Etienne Frossard, courtesy National Academy of Design

DB: The concept of borders, migration, and colonialism is central to the exhibition. How do you think the historical works in Past as Prologue resonate with contemporary issues surrounding these themes, particularly in our current sociopolitical climate?

SR: The historical works in the exhibition, especially those that were made by artists on expeditions like Alfred Thomas Agate, who accompanied the Wilkes Expedition between 1838 and 1842 make clear the hand artists had in documenting lands that were of interest to the colonial project. On view are works by Agate that detail landscapes in Fiji, American Samoa, and the Philippines.

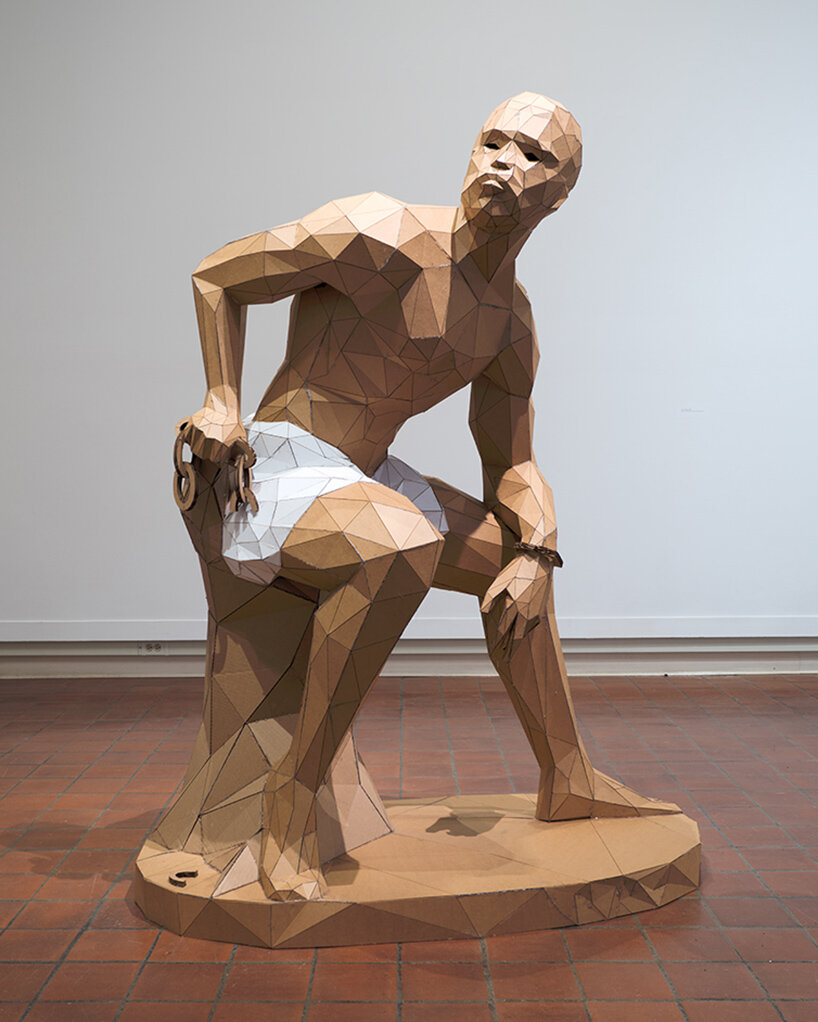

What excites me about looking at Agate’s oeuvre more than 150 years later is to think about the possibilities for art to impact society. If an artist could be part of such an expedition in 1840, and now artists can make art that revisits history in a participatory way, like Dread Scott’s Slave Rebellion Reenactment (2019) and Roberto Visani’s cardboard slave kits (2020-ongoing), I would propose that the relationship between the historical and contemporary visually attests to a radically different set of possibilities for art, what it can be and what it can do in society.

project info:

exhibition title: Past as Prologue: A Historical Acknowledgment, Part I

gallery: National Academy of Design | @natlacademy

location: 519 West 26th Street, New York, NY

curator: Sara Reisman (Chief Curator), Natalia Viera Salgado (Associate Curator)

exhibition essay: read here

on view: October 17th, 2024 — January 11th, 2025

photography: © Etienne Frossard

happening this week! holcim, global leader in innovative and sustainable building solutions, enables greener cities, smarter infrastructure and improving living standards around the world.

art interviews (158)

portraits (158)

PRODUCT LIBRARY

a diverse digital database that acts as a valuable guide in gaining insight and information about a product directly from the manufacturer, and serves as a rich reference point in developing a project or scheme.