norman foster scholarship winner charles palmer discusses cycling in megacities

image © daniela villalobos

for the past decade, british architectural firm foster + partners has awarded the RIBA norman foster travelling scholarship to one student in order to fund international research on a topic of their choice. this year, charles palmer of sheffield university school of architecture was awarded the prize for his proposal ‘cycling megacities’. the project took charles to cities in four developing countries — mexico city, mexico; lagos, nigeria; dhaka, bangladesh, and shenzhen, china, each of which present different challenges to bicycle advocacy and urban design. in an interview conducted by designboom español, palmer explains the scholarship, and discusses his findings.

mexico city, 2014

image © city clock magazine / via flickr

designboom: what is the RIBA norman foster travelling scholarship?

charles palmer: the RIBA norman foster travelling scholarship is an annual award given to a student of architecture and offers an opportunity for discovery that has the potential to lead to exciting new work in the field of architecture. I am the ninth recipient of the award, which has previously given others the chance to explore the relationship between architecture and recycling, cold environments, and water scarcity or abundance. I won this scholarship for my project ‘cycling megacities’.

evening traffic jam, mumbai

image CC adam cohn / via flickr

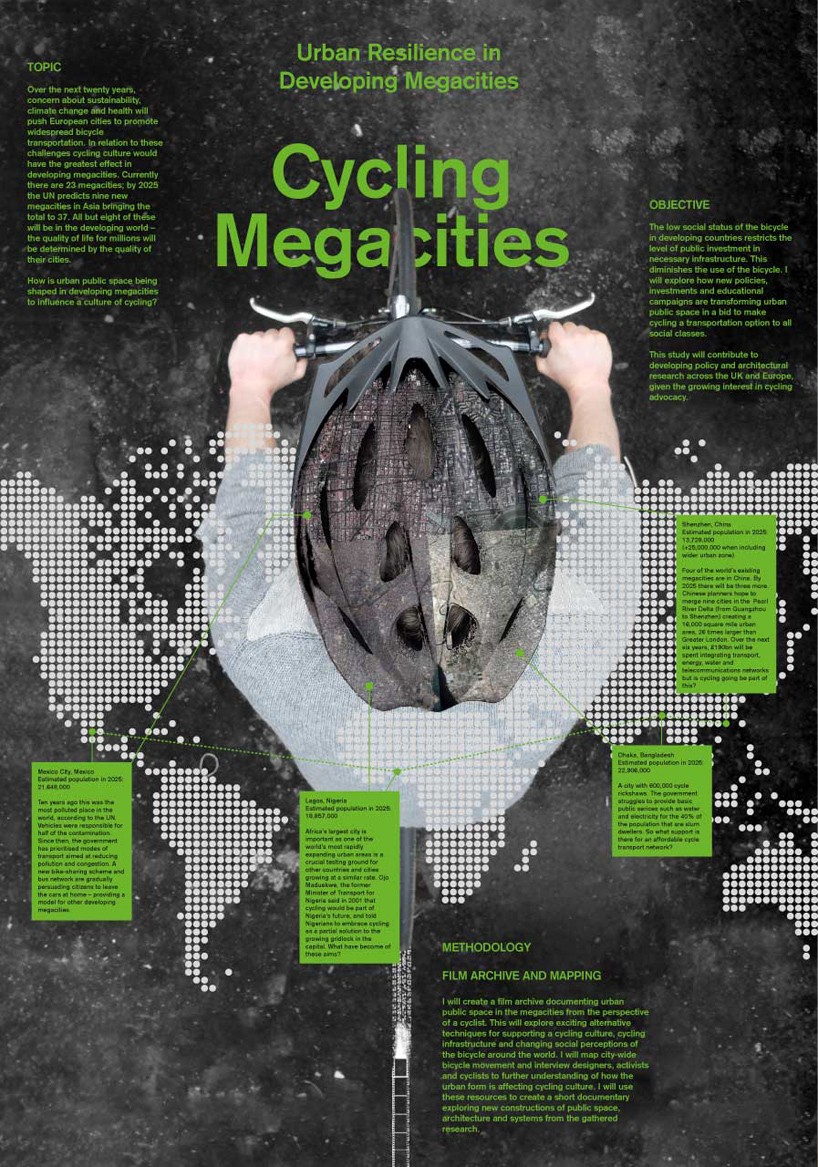

DB: what is ‘cycling megacities’ about?

CP: ‘cycling megacities’ is a study into the current conditions for cycling in cities of over ten million people. it has evolved from the idea that we should not only be looking at the small cities of copenhagen and amsterdam — where concepts of ‘life sized cities’ or ‘human scale cities’ have developed — for answers to the future of non motorized transportation. instead we should look at the mega metropolis for answers on how to design the sustainable cities of the future. over 55% of the world’s population now resides in urban areas, and this is only set to increase with developing nations still urbanizing rapidly. subsequently sustainable urban mobility is one of the greatest challenges of our time.

over the last 12 weeks I have circumnavigated the globe in order to visit ten megacities in countries the UN defines as developing: sao paulo, mexico city, hong kong, shenzhen, guangzhou, kolkata, dhaka, delhi, mumbai, and I am currently in bangalore. I have spent time in each city recording my experiences as I have explored the streets by bicycle and met cyclists, cycling activists, organizations and authorities that are shaping the future of mobility. ‘cycling megacities’ is not a comparative analysis of cycling infrastructure around the globe, it is an exploration into how large cities are growing, how macro and micro movement patterns have developed in expansive urban environments and whether cycling is a viable option in the mega metropolis.

bikes at the lights bao’an, shenzhen

image CC chris / via flickr

DB: what are the main problems for urban cyclists in developing countries?

CP: road safety, lack of infrastructure, lack of showering and parking facilities, and weather are all problems for bicycle users in developing countries, however the main problem for ‘cyclists’ in developing countries is the idea of who ‘cyclists’ are. until the idea of a cyclist as the sports person or as a poor man is removed from the equation, very few authorities are going to support cycle oriented development. in developed nations, where the levels of cycling directly correspond with the infrastructure present, there has been some debate around whether cycling infrastructure or a culture of cycling comes first.

in developing nations there is already a cycling culture without the infrastructural support because the bicycle has an important role as an affordable form of transportation available to the urban poor. in these contexts there is divide between the urban poor on affordable bicycles and a relatively new middle class on imported fixies, BMXs, road bikes, and hybrids. this divide has become a hindrance for the sustainable evolution of cycling in cities in developing countries, for the reason that a lot of new cycling infrastructure is aimed at the people who cycle little and for fun rather than those who use the bicycle as their main mode of transportation.

cycling sunday, mexico city

image CC carl campbell / via flickr

DB: how can we overcome these difficulties?

CP: in the short term these difficulties can be overcome by mass rides and road closures, where people from all social classes and politicians can come together and demonstrate that they all have equal rights to be on the streets. such rides have been happening all across the world, such as the ones that happen every week in latin american cities, the no car day in paris in september and the first ever mass ride and road closure for recreational cycling in delhi in october. these events are only a catalyst for society to rethink street space in the process towards the long term goal of equitable, livable streets.

today’s megacities are, among other things, the result of generations of racism and class-ism and struggles in the face of those discriminations alongside economic development and urbanization. as decades and centuries have gone by, racial boundaries have shifted yet class-ism and discrimination has remained due to pressures of a consumerist lifestyle that has followed. transportation has been near the heart of that struggle from the start. from housing choice to bus frequency to highway routing to pavement quality, cities have often failed to equitably distribute the costs and benefits of mobility. this has resulted in traffic jams, pollution and poor quality urban environments. we need to radically rethink how we investment into mobility networks to benefit as many people as possible and design a choice of transportation modes into our streets.

a broken rule, kolkata

image CC fluty chen / via flickr

DB: why did you choose to research mexico city of all latin american cities?

CP: I not only chose mexico city for its reputation of having a dangerous pollution problem, daily four hour plus long traffic jams, one of the largest urban sprawls on the planet and issues relating to urban inequality, but also because I had read and heard about new innovative schemes developing to combat these from the streets.

a woman riding a bike, shenzhen

image CC fluty chen / via flickr

DB: what did you find out?

CP: first of all, mexico city surprised me by being one of the most progressive cities for cycling that I have visited. there is a fantastic and engaged community of civil societies and NGOs advocating for cycling and other forms of non motorized transportation, an open, inclusive and innovative city authority and a rapidly expanding culture of cycling. while it was easy to see problems that the city was facing with increasing car ownership and double layer highways, it was also easy to see an optimistic future for the city and its residents.

when speaking to many of the actors involved with development in the city, they discussed mexico city as a ‘city within cities’. this philosophy provides an approach to looking at the urban area in a way that helps the understanding of real world urban movement, economic growth and even individual streets. it is a mindset that would be relevant for most of the megacities that I have visited, where they had previously been multiple cities close to one another that amalgamated over time. by adopting this mindset, other megacities would be able to follow in the footsteps of mexico city and address urban expansion while developing neighborhood specific pilot projects.

bike and stars, mexico city

image CC norbert grim / via flickr

CP (cont): another mode of thinking that excited me during my stay was demonstrated by the changes happening in policy and legislation around road safety. spearheaded by bicitekas (an influential civil society group working for sustainable and humane transportation in mexico city), new regulations were launched that will influence the way people move through the city, changing the behaviour of people through the enforcement of law and order. interestingly in these new laws, it is becoming legal for bicycle users to go through red lights on minor roads.

in legal terms this is written saying that on minor junctions, if a motorist is to hit a cyclist whether or not the cyclist has gone through a red light, they are liable for any harm done. this in turn raises the perceived risk for car drivers to be prosecuted. it has been implemented for three reasons: firstly, the natural state of cyclists is to continue rolling, secondly it is safer for cyclists to be ahead of traffic at junctions and thirdly that ‘people do it anyway’. this new regulation is going to be a fascinating test of the principles I have been studying: perception, safety and what actually happens in reality. will it cause more accidents at junctions? or will this result in safer, quieter and calmer minor junctions? we can only wait and see.

bi-cycles, dhaka

image CC tapan paul / via flickr

CP (cont): I also found that the security that cycling provides in mexico city is one that other forms of sustainable transportation cannot provide. cars are the only other solace to the gender associated challenges within the city and therefore, until harassment on public transport is significantly reduced, or other comfortable secure means of transportation are offered, any issues regarding sustainability, time spent in traffic and general health will come second to that of personal safety and security.

there is a large number of women who do cycle in mexico city. this is evident from the ecobici bike share scheme. when it began, only 5% of the 6500 daily users were female. now the scheme has over 200,000 daily users, with over 35% of them female. this is significantly higher than the percentage of trips undertaken in mexico city that are taken by females. whether this is instead representative of the neighborhoods that ecobici is based in, I do not know, but it demonstrates a significant social contribution to equality based transportation in the city.

‘cycling megacities: urban resilience in developing megacities’

CP (cont): the wide scope of people I met in mexico city and the experiences I have had cycling around the city have given me a very optimistic outlook on the development of sustainable transportation in the city. it is very difficult to summarize all the that I found there, I could go on about the infrastructure and the inspiring pilot projects being undertaken by SEMOVI (mobility department of the federal district – formerly of transportation and highways) and laboratorio para la ciudad (laboratory for the city).

the large number of people enacting change and challenging the damaging trends we are currently on and proposing realistic alternatives is inspiring. all the organizations I spoke to have worked or are working together in some way and with such a network it will be remarkable if the modal share of cycling in the city does not increase to rival european cities a quarter of the size. it is therefore the real testing ground for a multi modal megacity.