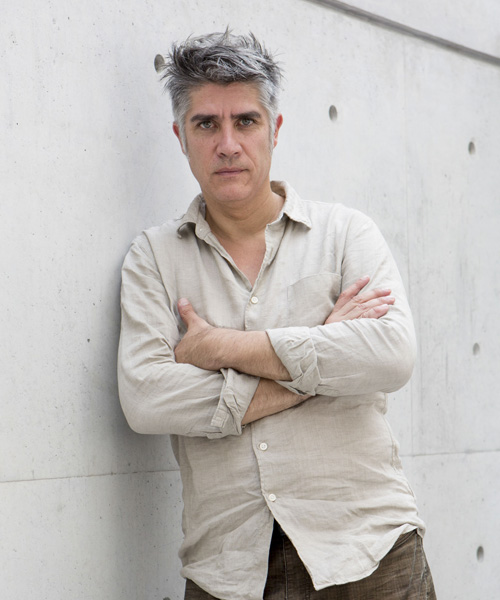

alejandro aravena discusses his design principles and ongoing projects

chilean architect alejandro aravena is a founding partner and executive director of the santiago-based practice elemental. the studio focuses on architecture projects of public interest and social impact, including housing, public space, infrastructure, and transportation. elemental encourages a participatory design process in which the architects work closely with both the public and end user. the firm has also pioneered an approach termed ‘incremental housing’, where residential designs leave space for residents to complete their dwellings, enhancing the value of their property, thus raising themselves up to a better standard of living. in 2015, aravena was appointed curator of the 15th venice architecture biennale, before being awarded the pritzker architecture prize in early 2016.

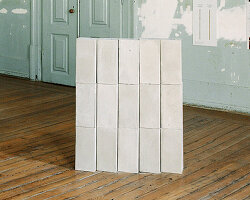

elemental has made projects such as monterrey housing in mexico ‘open source’

image by ramiro ramirez

see more of the project on designboom here

to understand more about alejandro aravena’s architectural projects, designboom spoke with the architect who discussed his opinions in further detail. read his answers in full below, and see our previous conversation here.

designboom: you have made your own projects available for anyone to download. can you expand on the idea behind that?

alejandro aravena: in the built environment all the incentives are on the second mover, like in agriculture. I mean, if you want to do something different you have to invest in the innovation. let’s start on agriculture then move into the built environment; nobody has planted kiwis before here, everybody has been planting for decades corn, weed, whatever it is. then somebody says: ‘well, with this weather maybe we should try kiwis’. so you have to do a little bit of research, take the risk and dedicate part of your land to kiwis. if you succeed, the guy next door will look at you and if you grew them properly, then he will do kiwis too. if you fail, then you have to swallow all of your losses alone. so everybody is waiting for the guy next door to move first. you cannot protect your innovations in agriculture, nor in the built environment.

we are building millions of units every year in social housing, and we all agree that it is not a great thing, inequality is bad, but then you are matching budgets and apparently you can’t improve. if you’re a private building company, even if you’re a government, and you say ‘well what if we try to do it differently?’, then you make risk quantity which is a big issue. thousands of families may not get their thing because you are trying to do it in a better way and it may take some time, until you understand the innovation. so everybody is waiting for their neighbor to move first and there are many excuses that you are given when you as an architect say, ‘look, we may have something new here that makes more efficient use of the land’.

UC innovation center – anacleto angelini, 2014, san joaquín campus, universidad católica de chile, santiago, chile

image by nina vidic

see more of the project on designboom here

(continued) so instead of choosing bigger houses, but far away, or better located tiny units, there is a way to do both. with a good location there is the potential to become a middle class standard housing unit. you will be given a thousand reasons why that is not possible — so nobody is willing to take the risk to move ahead. then if I need to develop a new plan then I will have to pay you some money. and if this might succeed then my neighbor or another building company will copy me. so this was the history of our own development as a company at elemental. at the beginning they said, ‘no it is impossible for $7,000, you can’t do location and middle class standards simultaneously.’ so we found a guy that was willing to take the risk and build our first project, which proved that we could build in places of the city where land costs three times more than what social housing was normally paying for. meaning they are much better located, with units with the potential to gain value over time from the initial cost of $7,000. we found out a couple of months ago that some of them sold for $65,000. that is a huge value gain that normally doesn’t happen in social housing.

after we built our first project, the market or the government was saying, ‘yeah but you built in a city where it doesn’t rain, so it was too easy’ and so we built in other cities where there was rain. and then their excuse was, ‘these are not big cities, these are middle-sized cities’, so we built them in a metropolis. there was always an excuse and then they would say, ‘but you have all of these innovative designs that meet the budget, meet the rule of law, they comply with everything but we still had to pay for the design’. so we said, ‘you know what? here, you have the design’. so if you want to come up with another excuse, it will be clear because there is no willingness to do it differently. so it was trying to take one more excuse out, and for sure there will be another excuse coming but this is the thing, try to put pressure on the market, on the government so that there are less excuses left for not doing it better. because for the same amount of money it cannot be done better. that was the thing.

the venice architecture biennale’s introductory room

image © designboom

see more of the project on designboom here

DB: do you think that architectural education needs to change?

AA: yes, what we’re witnessing more and more in academia is that you have to create a fake question to make it seem as if you are solving a problem. in reality, it comes with a lot of constraints which should be the starting point, but we tend to assume that in order to develop your creative freedom and allow you to ‘fly free’, you need to take out those constraints; develop your creativity by doing whatever you want. I think that’s an awful mistake, the more constraints the more of a need there is for creativity. there are no rules, there is no freedom. that’s the first thing I think should change; put a lot of constraints through the problems because the degrees of freedom are going to be clearly necessary and be able to be measured: what’s your contribution to a given question?

secondly, you in reality cannot accommodate the constraints. if you are getting something that is not needed, is not cool or is not ready for being published, in academia you tend to accommodate the question, ‘well this is becoming too ugly’ or ‘not cool enough’, then I will change my question. we can’t do that in reality and that is the power of reality, which is what I think I really like: the fact that the forces are made but we cannot control them.

las cruces pilgrim lookout point, 2010, jalisco, mexico

image by iwan baan

see more of the project on designboom here

(continued) it is up to you to be able to jump into those powerful forces that are shaping the built environment and be able to navigate instead of accommodating them for your own creative convenience — and that is not normally the case in academia. it is very difficult in architecture to be able to go and do projects for your own education, it would be impossible. so that is why the kind of ‘master-apprentice’ approach works: come to the real thing, sit on the side and watch until you feel you get the constraints, understand the language, understand the failure and frustration. you need to dig in order to discover. eventually, you will learn from that. so witnessing and being exposed to things more than artificially creating the laboratory thing, is something that I somehow intuitively believe should be the approach to architecture, to transfer knowledge from one generation to the other.

in the nature of architecture there is something in creating this parallel reality, even well intentioned for educational, pedagogic purposes. then there is a moment where that parallel universe became a goal in itself, and then you live in the parallel universe where nobody is interested in the society: not the people, not the decision makers, not other professionals, just other architects. that is the risk of endogamy. being relevant is just too high, so that is why we’ll need a new approach.

constitución seaside promenade, 2014, constitución, chile

image by felipe diaz

DB: can you tell us about any projects you are currently working on?

AA: one third of our time in the office is social housing, so we still try to tackle the issue of accommodating to cities. in principal this is great news with very limited resources which require an incremental approach to the problem — meaning that the amount of money available is not enough, it’s a fact to provide a dissident, living unit. actually, the available money is in the form of subsidies, public policies or personal savings, allowing us to build just half of that required space. this is not a choice, I mean it happens that way. so we can choose whether we engage in that set of rules or we stay outside that. which all implies that somebody else will be delivering solutions, maybe even worse, anyhow. so one third of our design is given the set of rules, we try to do better. in parallel, we are trying to change the set of rules if there is room for that to be made. we change those rules by proving with concrete examples that it could have been done differently, so it is a balance between doing within the set of rules and then trying to change the set of rules with evidence — which are the projects themselves.

bicentennial children’s park, 2012, santiago, chile

image by cristobal palma

(continued) another third of our time is buildings that could be, let’s say, more conventional from an architect. and then another third is city design where you involve communities and participatory processes on an entire city level, sometimes because of conflicts, social-political politics or environmental conflicts. then you try to channel all of those forces through the design of cities that are in a sense, a shortcut towards quality. if you identify projects in the city, public space, transportation, infrastructure or social housing then you can improve quality of life right here, right now, which is a very efficient way to correct inequalities. we try to balance all three of them, not just privilege one or the other.

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save